National Savings and Warship Weeks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Congresbury Has Grown

How Congresbury has grown A report for Congresbury Parish Council Authors: Tom Leimdorfer, Stuart Sampson Publication June 2015 Updated January 2018 Population and properties in Congresbury January 2018 [1] Congresbury Key Figures Population 3497 Age breakdown Source: Census 2011, National Office for Statistics Population and properties in Congresbury January 2018 [2] Household properties 1475 Population and properties in Congresbury January 2018 [3] How Congresbury has changed over 100 years The population of Congresbury grew by just over 450 people between 1901 and 1961. During the 60’s the population of the village doubled as by 1971, the census showed 3397 people. This can be seen in diagram 1. Diagram 1 – Total population reported in Congresbury1 A large part of this growth was due to the action of Axbridge Rural District Council in the post-war years to build the Southlands council estate to ensure that local working people had homes in which they could afford to live. Even at that time, when a cottage in the old part of the village became vacant it fetched a price which local young couples could not raise. The Rev. Alex Cran’s history of Congresbury recounts the tensions of the time. Opposition to the Southlands estate came from those who wanted ‘infill’ amongst the rest of the village, but such a scheme would have been too expensive (p216 ‘The Story of Congresbury’). Bungalows in Well Park were partly aimed at persuading older residents to move to smaller houses from Southlands and vacate the larger dwellings for families. Many homes in Southlands Way, Southside and Well Park are now privately owned. -

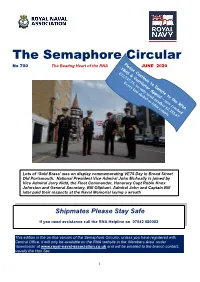

Semaphore Circular No 700 the Beating Heart of the RNA JUNE 2020

The Semaphore Circular No 700 The Beating Heart of the RNA JUNE 2020 Lots of ‘Gold Brass’ was on display commemorating VE75 Day in Broad Street Old Portsmouth. National President Vice Admiral John McAnally is joined by Vice Admiral Jerry Kidd, the Fleet Commander, Honorary Capt Robin Knox Johnston and General Secretary, Bill Oliphant. Admiral John and Captain Bill later paid their respects at the Naval Memorial laying a wreath Shipmates Please Stay Safe If you need assistance call the RNA Helpline on 07542 680082 This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec 1 Daily Orders (follow each link) Orders [follow each link] 1. NHS and Ventilator Appeal 2. Respectful Joke 3. BRNC Covid Passing out Parade 4. Guess the Establishment 5. Why I Joined The RNA 6. RNA Clothing and Slops 7. RNA Christmas card Competition 8. Quickie Joke 9. Dunkirk 80th Anniversary 10. The Unusual Photo 11. A Thousand Good Deeds 12. VC Series - Lt Cdr Eugen Esmonde VC DSO MiD RN 13. Cenotaph Parade 2020 14. RN Veterans Photo Competition 15. Answer to Guess the Establishment 16. Joke Time IT History Lesson 17. Zoom Stuff 18. And finally Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman -

Documentary and Photographic Survey YATTON

YCCCART 2018/Y3 Congresbury Bridge: Documentary and photographic survey YATTON, CONGRESBURY, CLAVERHAM AND CLEEVE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH TEAM (YCCCART) General Editor: Vince Russett Congresbury bridge early 20th century. Courtesy of Congresbury History Group Congresbury, Documentary and photographic survey, Congresbury Bridge, 2018, Y3, v1 1 Page Contents 3 Abstract Acknowledgements Introduction 4 Site location Geology and land use 5 Historical & archaeological context 24 References Congresbury, Documentary and photographic survey, Congresbury Bridge, 2018, Y3, v1 2 Abstract Research has established that there was a bridge at Congresbury earlier than 1551. A new stone bridge was built in 1710, which by 1904 had a raised parapet and steel girders. This was replaced in 1924 by the current bridge. Acknowledgements Our thanks to Vince Russett for suggesting this project, John Wilcox for his excellent photographic work and Maureen Bews and Anne Dimmock for typing up transcriptions. Introduction Yatton, Congresbury, Claverham and Cleeve Archaeological Research Team (YCCCART) is one of a number of Community Archaeology teams across northern Somerset, formerly supported by the North Somerset Council Development Management Team. Our objective is to undertake archaeological fieldwork to enable a better understanding and management of the heritage of the area while recording and publishing the activities and locations of the research carried out. Congresbury, Documentary and photographic survey, Congresbury Bridge, 2018, Y3, v1 3 Site location Fig 1: Site location indicated by the red arrow. Land use and geology The current bridge (and the earlier) stand on the estuarine alluvium of the Northmarsh Solid geology at the site is of the Mercia Mudstones, which outcrop at the parish church to the west and in the High Street to the east. -

Somerset. Axbridge

TlrRECTORY. ] SOMERSET. AXBRIDGE. 31 'The following places are included in the petty sessional Hutton, Kewstoke, Locking, Loxton, Lympsham, Markx division :-Axbridge, Badgwortb, Banwell, Berrow, Hutton, Kewstoke, Locking, Loxton, Lympsham, Biddisbam, Blagdon, !Bleadon, Brean, Brent Knoll, Burn Markx, Nyland-with-Batcombe, Puxton, Rowberrow, ;ham. Burnham Without, Burrington, Butcombe, Chapel Shipham, Uphill, Weare, Wedmore, Weston-super .AIle.:rton, Charterhouse (ville), Cheddar, Christon, Mare, Wick St. Lawrence, Winscombe, Worle, Wring 'Churchill, Compton Bishop, Congresbury, East Brent, ton-with-Broadfield. The population of the union in ;Highbrid-ge North, Highbridge South, Hutton, Kew 1891 was 43,189 and in 1901 was 47,915; area, 97,529; ·stoke, Locking, Loxton, Lympsham, Mark, Nyland & rateable value in 1897 was £234,387 'Batcombe, Puxton, Rowberrow, Shipbam, UphiIl,Weare, Cbairman of the Board of Guardians, C. H. Poole 'Wedmore, Weston-supe.:r-Mare, Wick St. Lawrence, Clerk to the Guardians & Assessment Committee, William 'Winscombe, Worle &; Wrington Reece, West street, Axbridge AXBRIDGE RURAL DISTRICT COUNCIL. Treasurer, John Henry Bicknell, Stuckey's Bank Collector to the Guardians, William Reece, West street ?lIeet at the Board room, Workhouse, West street, on 3rd Relieving & Vaccination Officers, No. 1 district, F. E. Day, friday in each month at II a. m. Eastville, Weston-super-Mare; No. 2 district, Herbert Chairman. W. Petheram W. Berry, Churchill; No. 3 district, Frederick Curtin, Clerk, William Reeca, West street Wedmore; No. 4 district, R. S. Waddon, Brent Knoll Treasurer, John Henry Bicknell, Bank ho. Stuckey's Bank Medical Officers & Public Vaccinators, No. 1 district, A. B. :MedicaI Officer of Health, .A.rtbur VictDr Lecbe L.R.C.P. -

Ajax New Past up For

H.M.S. Ajax & River Plate Veterans Association NEWSLETTER SEPTEMBER 2014 CONTENTS Chairman/Editor's Remarks Visit to Canada – Malcolm Collis Richard Llewellyn and D Day Halifax and HMS AJAX Link Archivist Report Membership Secretary Report Lost Ship Mates Application Forms NEC QUISQUAM NISI AJAX 2. 3. H.M.S. AJAX & RIVER PLATE VETERANS ASSOCIATION. 2015 – 50th Year of the Association. I have asked in previous newsletters for your thoughts on how CHAIRMAN/SECRETARY ARCHIVIST th we should mark the 50 Year of the Association. When I hear of many Associations that are closing NEWSLETTER EDITOR Malcolm Collis down due to reducing numbers, it is pleasing to know that we continue to find new members. But it is Peter Danks ‘The Bewicks’, Station Road those of you who have been with us since the Association was in its infancy that I need to hear from, so 104 Kelsey Avenue Ten Mile Bank, that the committee can continue to give Members what they wish to see. It is your Association, SO Southbourne Downham Market PLEASE let any of the committee members know your views and we will try to meet them. Emsworth Norfolk PE38 0EU Hampshire PO10 8NQ Tel: 01366 377945 Article from Halifax. Many people have asked me what the connection with Halifax is and I am Tel: 01243 371947 [email protected] grateful to Mrs Sue Hanson for sending me the article from the Halifax Courier which explains it all. [email protected] MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY AGM Agenda. 1. Chairman's Remarks 2. Apologies 3. Minutes of last meeting TREASURER Mrs Judi Collis 4. -

The Mineralogical Magazine Aiid Journal of the Mineralogical Society

THE MINERALOGICAL MAGAZINE AIID JOURNAL OF THE MINERALOGICAL SOCIETY No. 174 September, 1941 Vol. XXVI Mineral localities on the Mendip Hills, Somerset. By ARTHUR W. G. KINGSBURY. [Read March 7, 1940.] THOUGH the Mendip Hills, as a district, have from time to time ~j~received the attention of geologists, details of the mineral occur- rences are, on the whole, remarkably scarce. Mining was formerly carried on on the Hills for many centuries, but mineralogy as a science had not been sufficiently developed at the time when the mines were most active, and little interest was taken in the minerals other than those suitable or required for commercial and industrial purposes. Even in later years, when, in the course of treating old refuse and tailings left by earlier miners and of various attempts to resuscitate the mining industry, much material must have been available for examina- tion, little attention seems to have been paid to it, or to the numerous quarries that were opened in the Carboniferous Limestone. Mention of a few mineral species has been made by writers from.time to time, but up to the beginning of last century, by which time practi- cally all work at the mines had ceased, the majority of accounts give little detail and were still concerned more with the commercial as~ct. Much interesting information about the old mines has been extraoted from old records and put together by J. W. Gough in his book 'The mines of Mendip', 1 but apart from a few general remarks on the minerals, he is more interested in, and treats, the subject from an historical point of view. -

Wessex-Cave-Club-Journal-Number

Journal No. 130, Vol. 11 August 1970 CONTENTS Page Club News 77 Charging Nife Cells to get Maximum Light, Bob Picknett 79 Home Made Nylon Boiler Suits for Caving, H. Pearson and D. Tombs 81 The Extension of Poulawillin, Co. Clare, C Pickstone 92 An Ear to the Ground 94 Northern Notes, Tony Blick 96 Water Tracing on Mendip - Tim Atkinson 98 Reviews 97 & 99 List of Members 100 The Complete Caves of Mendip - review 107 * * * * * * * * * * Hon. Secretary: D.M.M. Thomson, “Pinkacre”, Leigh-on-Mendip, Bath. Asst. Secretary: R.J. Staynings, 7 Fanshawe Road, Bristol, BS14 9RX. Hon. Treasurer: T.E. Reynolds, 23 Camden Road, Bristol, BS3 1QA. Subs. Treasurer: A.E. Dingle, 32 Lillian Road, London S.W. 13. Hut Warden: M.W. Dewdney-York, Oddset, Alfred Place, Cotham, Bristol 2. Journal Distribution: Mrs. B.M. Willis, Flat 2, 40 Altenburg Gardens, London S.W. 11. Club Meets: Jenny Murrell, 1 Clifton Hill, Bristol, BS8 1BN. Editor: M.D. Newson, 60 St. Mary’s Street, Wallingford. or Institute of Hydrology, 28 St. Mary’s Street, Wallingford. CLUB NEWS There is a feeling among Committee Members that much of the discussion ought to be extended to the general membership. On the whole the Committee has worked harmoniously over the last few years, but last meeting feelings ran high when some Members started wagging their fingers and beards at others whom they thought contributed less to the Club than was politic. The accused shifted nervously from one buttock to the other, while others, caught in the crossfire, sided one way or the other. -

How Congresbury Has Grown

How Congresbury has grown A report for Congresbury Parish Council Authors: Tom Leimdorfer, Stuart Sampson June 2015 Population and properties in Congresbury June 2015 [1] Congresbury Key Figures Population 3497 Age breakdown Source: Census 2011, National Office for Statistics Population and properties in Congresbury June 2015 [2] Household properties 1475 Population and properties in Congresbury June 2015 [3] How Congresbury has changed over 100 years The population of Congresbury grew by just over 450 people between 1901 and 1961. During the 60’s the population of the village doubled as by 1971, the census showed 3397 people. This can be seen in diagram 1. Diagram 1 – Total population reported in Congresbury1 A large part of this growth was due to the action of Axbridge Rural District Council in the post-war years to build the Southlands council estate to ensure that local working people had homes in which they could afford to live. Even at that time, when a cottage in the old part of the village became vacant it fetched a price which local young couples could not raise. The Rev. Alex Cran’s history of Congresbury recounts the tensions of the time. Opposition to the Southlands estate came from those who wanted ‘infill’ amongst the rest of the village, but such a scheme would have been too expensive (p216 ‘The Story of Congresbury’). Bungalows in Well Park were partly aimed at persuading older residents to move to smaller houses from Southlands and vacate the larger dwellings for families. Many homes in Southlands Way, Southside and Well Park are now privately owned. -

1 Jul Highways and Public Rights of Way Notices [463.94

Town and Country Planning Act 1990 Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (England) Order 2015 Notice under Article 15 Planning (Listed Building & Conservation Areas) Act 1990 Notice under Section 67 & 73 You may inspect the following applications and make representations at www.n-somerset.gov.uk/planning or in writing to: Planning, Post point 15, North Somerset Council, Town Hall, Weston-super-Mare, BS23 1UJ. All comments should be received within 21 days of this notice and will be displayed on our website. Your comments should not be offensive or defamatory. If we refuse permission there may be no further opportunity to object to an appeal on a householder application. We are registered with the Information Commissioner’s Office for the purposes of processing personal data, which we do in accordance with EU and UK data protection law. For details visit www.n- somerset.gov.uk/planningprivacystatement. If you have any concerns about how your data is handled, contact us at [email protected] Application in a Conservation Area 21/P/1593/FUH - Demolition of conservatory and proposed erection of a single storey rear extension at 24A Long Ashton Road, Long Ashton. Application affects the setting of a Listed Building in a Conservation Area 21/P/1653/FUH - Demolition of existing conservatory and single storey rear extensions; proposed erection of a two storey rear extension and single storey rear extension, extending the existing driveway & associated internal and external alterations at The Cottage, Clevedon Road, Weston-in-Gordano. Application affects the setting of a Listed Building 21/P/1575/FUL - Change of use of existing stables to holiday let at the Stables, Moor Lane, Clevedon. -

VILLAGE NEWS 82 Saturday MARKET

BLEADON VILLAGE NEWS 82 Saturday MARKET 19th September,17th October, 21st November 5th December Christmas Market 16th January, 20th Febraury Bleadon Village Coronation Hall 9-12.30 Local produce. Somerset beef and lamb. Local bread. Fairtrade. Home-made cakes. Cheeses. Cider. Honey. Preserves. Plants. Books. Crafts. Jewellery. Gifts. Cards. Bric-a-brac. Please bring a bag Meet friends and chat over coffee and snacks 01934 812 370 for stalls info Bleadon VillageParish Council News [70] THE PARISH COUNCIL PENNY SKELLEY [CHAIRMAN] ’MENDIP CROFT’, CELTIC WAY, BLEADON. TEL. 815331 PENNY ROBINSON [VICE CHAIRMAN] 1,THE VEALE, BLEADON. TEL. 814142 GRAHAM LOCKYER ‘HIGHCROFT’ ROMAN RD. BLEADON. TEL. 812050 MARY SHEPPARD ‘LITTLEWOOD’ BRIDGWATER RD., LYMPSHAM. TEL. 812921 KEITH PYKE 8, WHITEGATE CLOSE, BLEADON. TEL. 813127 CLIVE MORRIS 20, BLEADON MILL, BLEADON. TEL. 811591 BRIAN GAMBLE ‘ASHDENE’ BLEADON RD., BLEADON. TEL. 811709 I.D. CLARKE ‘THE GRANARY’ MULBERRY LANE, BLEADON. TEL. 815182 ROBERT HOUSE LAKE FARM COTTAGES, SHIPLATE ROAD, BLEADON. TEL. 815588 The Council meets on the 2nd Monday of the month at 7.30pm, in the Coronation Hall. An agenda is published on the Parish notice board, and any Parishioner who wishes to, may attend these meetings. If there is a particular issue you would like to raise, could you please let the Parish Clerk know in advance and at the latest by the Friday immediately preceding the meeting. This will give him the chance to collect the most up to date information available. THE PARISH CLERK TO WHOM ALL CORRESPONDENCE SHOULD BE ADDRESSED IS:- BRUCE POOLE, ‘THE CHIPPINGS’, 21 STONELEIGH CLOSE, BURNHAM-ON- SEA, SOMERSET TA8 3EE TEL. -

A Glimpse of Edwardian Worle

WORLE HISTORY SOCIETY A Glimpse of Edwardian Worle Raye Green 1/10/2018 A decade in the life of the village of Worle and its people, against a background of national events. Illustrations include photographs, charts and tables. By the end you will be happy to have met the folk who formed the foundations of modern life in this Somerset village which grew into a suburban town. Raye Green Edwardian Worle For the members of Worle History Society who have contributed so much to the content of this book with all my heartfelt thanks. 1 Raye Green Edwardian Worle A Glimpse of Edwardian Worle Contents Chapters 1. Introduction 3 2. The Edwardian Era 4 3. His Majesty’s Heads of Government 7 4. Worle’s Men at Westminster 9 5. Worle in 1900 11 6. Censuses and Population of Worle 12 7. Ordnance Survey Map of Worle, 1904 14 8. The Bedrock of Worle 15 9. Upstairs, Downstairs: 16 Fairfield 17 Hillside 19 Sunnyside 23 Springfield 26 Ivy Lodge 29 10. Last weeks of Victoria Regina 31 11. Worle Parish Council 36 12. Vicars of St. Martins 42 13. Edwardian Worshippers 50 14. Bell ringers of St. Martin’s 51 15. The Methodist Chapel 53 16. A Man of His Time, A. B. Badcock 54 17. The Churchyard Question 58 18. The Sanitary Condition of Worle 61 19. Transport and Getting Around 65 20. Schools and Education 67 21. Summer of 1902 71 22. Crowning of Edward and Alexandra 75 23. Harvest Home 76 24. Worle Lads before the Bench 79 25. -

13 Feb Highways and Public Rights of Way Notices

Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 - Section 14 Notice of Temporary Traffic Regulation Order 2020 Loxton Road and Canberra Road, Weston-super-Mare, North Somerset Temporary Prohibition of Use by Vehicles Order 2020 Date coming into force: 17 February 2020 Ref: T20-14 Notice is hereby given that North Somerset Council in pursuance of the provisions of section 14 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, as amended, have made an order the effect of which will be to close, temporarily, to vehicles the lengths of roads specified in the schedule to this notice. This order was required because of carriageway patching works and will become operative on 17 February 2020 for a maximum period of 18 months. However, the closures may not be implemented for the whole of the period but only as necessitated by the works which is anticipated to be 5 days in duration between 8am and 5pm. Schedule - Loxton Road for the full extents of the road. Canberra Road for the full extents of the road. Alternative routes see https://northsomerset.roadworks.org/ For further information www.n-somerset.gov.uk/roadworks North Somerset Council, Town Hall, Weston-super-Mare BS23 1UJ 01934 888 802 Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 - Section 14 Final Notice of Temporary Traffic Regulation Order 2020 Wheatfield Drive, Wick St Lawrence, North Somerset Temporary Prohibition of Use by Vehicles Order 2020 Date coming into force: 26 February 2020 Ref: T20-426 Notice is hereby given that North Somerset Council in pursuance of the provisions of section 14 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, as amended, have made an order the effect of which will be to close, temporarily, to vehicles the lengths of roads specified in the Schedule to this Notice.