Auditor Liability in Securities Litigation from a Defense Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Matching Gifts

Corporate Matching Gifts Your employer may match your contribution. The Corporations listed below have made charitable contributions, through their Matching Gift Programs, for educational, humanitarian and charitable endeavors in years past. Some Corporations require that you select a particular ministry to support. A K A. E. Staley Manufacturing Co. Kansas Gty Southern Industries Inc Abbott Laboratories Kemper Insurance Cos. Adams Harkness & Hill Inc. Kemper National Co. ADC Telecommunications Kennametal Inc. ADP Foundation KeyCorp Adobe Systems, Inc. Keystone Associates Inc. Aetna Inc. Kimberly Clark Foundation AG Communications Systems Kmart Corp. Aid Association for Lutherans KN Energy Inc. Aileen S. Andrew Foundation Air Products and Chemicals Inc. L Albemarle Corp. Lam Research Corp. Alco Standard Fdn Lamson & Sessions Co. Alexander & Baldwin Inc. LandAmerica Financial Group Inc. Alexander Haas Martin & Partners Leo Burnett Co. Inc. Allegiance Corp. and Baxter International Levi Strauss & Co. Allegro MicroSystems W.G. Inc. LEXIS-NEXIS Allendale Mutual Insurance Co. Lexmark Internaional Inc. Alliance Capital Management, LP Thomas J. Lipton Co. Alliant Techsystems Liz Claiborne Inc. AlliedSignal Inc. Loews Corp. American Express Co. Lorillard Tobacco Co. American General Corp. Lotus Development Corp. American Honda Motor Co. Inc. Lubrizol Corp. American Inter Group Lucent Technologies American International Group Inc. American National Bank & Trust Co. of Chicago M American Stock Exchange Maclean-Fogg Co. Ameritech Corp. Maguire Oil Co. Amgen In c. Mallinckrodt Group Inc. AmSouth BanCorp. Foundation Management Compensation AMSTED Industries Inc. Group/Dulworth Inc. Analog Devices Inc. Maritz Inc. Anchor/Russell Capital Advisors Inc. Massachusetts Mutual Life Andersons Inc. Massachusetts Financial Services Investment Aon Corp. Management Archer Daniels Midland Massachusetts Port Authority ARCO MassMutual-Blue Chip Co. -

Thomas Johnson, Et Al. V. Tellabs, Inc., Et Al. 02-CV-04356

Case 1:02-cv-04356 Document 379 Filed 08/13/10 Page 1 of 120 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION MAKOR ISSUES & RIGHTS, LTD., ) CHRIS BROHOLM, RICHARD LEBRUN, ) et al., ) Plaintiffs, ) )Case No. 02 C 4356 v. ) )Honorable Judge Amy J. St. Eve TELLABS, INC., MICHAEL J. BIRCK, ) RICHARD C. NOTEBAERT, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER AMY J. ST. EVE, District Court Judge: Before the Court is Defendants Tellabs, Inc. (“Tellabs”), Michael J. Birck, Brian J. Jackman, Richard C. Notebaert, and Joan A. Ryan’s (collectively “Defendants”) Motion for Summary Judgment. Defendants seek summary judgment on each of the remaining claims set forth in Plaintiffs Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd., Chris Broholm, and Richard Lebrun, et al. ’s (collectively “Plaintiffs”) Second Amended Consolidated Class Action Complaint (“Complaint”). For the following reasons, the Court grants in large part and denies in part Defendants’ motion for summary judgment and grants in part and denies in part Defendants’ Motion to Strike. BACKGROUND I. Procedural History This case has a long procedural history. In June 2002, Plaintiffs filed a putative class action lawsuit on behalf of various individuals and persons who purchased common stock of Defendant Tellabs between December 11, 2000 and June 19, 2001 pursuant to § 10(b) of the Case 1:02-cv-04356 Document 379 Filed 08/13/10 Page 2 of 120 Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 (“Section 10(b)”) and SEC Rule 10b-5, 17 C.F.R. § 240.10b-5 (“Rule 10b-5”). The Court has jurisdiction over this matter pursuant to 15 U.S.C. -

Ctpf Illinois Economic Opportunity Report

CTPF ILLINOIS ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY REPORT As Required by Public Act 096-0753 for the period ending June 30, 2021 202 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE I 1 Illinois-based Investment Manager Firms Investing on Behalf of CTPF TABLE II Illinois-based Private Equity Partnerships, Portfolio Companies, 2 Infrastructure, and Real Estate Properties in the CTPF Portfolio TABLE III 14 Illinois-based Public Equity Market Value of Shares Held in CTPF’s Portfolio TABLE IV 18 Illinois-based Fixed Income Market Value of Shares Held in CTPF’s Portfolio TABLE V Domestic Equity Brokerage Commissions Paid to Illinois-based 19 Brokers/Dealers TABLE VI 20 International Equity Brokerage Commissions Paid to Illinois-based Brokers/Dealers TABLE VII Fixed Income Volume Traded through Illinois-based Brokers/Dealers 21 (par value) 2021 CTPF ILLINOIS ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY REPORT REQUIRED BY PUBLIC ACT 096-0753 FOR THE PERIOD ENDING JUNE 30, 2021 TABLE I Illinois-based Investment Manager Firms Investing on Behalf of CTPF Table I identifies the economic opportunity investments made by CTPF with Illinois-based investment management companies. As of June 30, 2021, Total Market/Fair Value of Illinois-based investment managers was $3,121,157,662.18 (23.74%) of the total CTPF investment portfolio of $13,145,258,889.14. Market/Fair Value % of Total Fund Investment Manager Firms Location As of 6/30/2021 (reported in millions) Adams Street Chicago $ 319.69 2.43% Ariel Capital Management Chicago 83.44 0.63% Attucks Asset Management Chicago 274.06 2.08% Ativo Capital Management1 Chicago -

A Tribute to Our Teachers 2018 Annual Report

PROVIDENCE ST. MEL SCHOOL A Tribute to our Teachers 2018 ANNUAL REPORT We are grateful to those who are the heartbeat of our school and our success —the teachers! A Tribute to our Teachers 2018 Annual Report The educators of Providence St. Mel School walk alongside our students everyday, inspiring them to live up to their potential and build upon our legacy of integrity and academic excellence. A Tribute to Our Teachers 2 | A Tribute to Our Teachers Since 1978, the march toward a quality education and a A Providence St. Mel education has profound impact on the better, brighter, and richer future for all has been the lives of our students and exemplifies for future generations that, foundation of the mission and vision of Providence St. Mel no matter the adversities they face along the way, they too can School. Our tradition of success on Chicago’s West Side has succeed. Unlike other schools in our West Side community, our been unrivaled, not only locally but nationally. Let us not perfect college acceptance rate is accompanied by a drastic forget who has been at the forefront of our success – our improvement in standardized test performance. The average incredible and tremendous faculty and staff. Our teachers student that enters Providence St. Mel School as a freshman touch the lives of our students daily, and we know their will increase their ACT score by 7-8 points from 9th grade to impact can influence the trajectory of a student’s life, 11th grade. The Class of 2018 boasts an average ACT score of empowering them to realize that they are capable and 25! As a result of this hard work, universities throughout the committed individuals. -

Final Report Nasdaq-100

FFRREEDDEERRIICC WW.. CCOOOOKK && CCOO..,, IINNCC.. 2001 BOARD OF DIRECTORS PROFILE AND COMPENSATION AT NASDAQ-100 COMPANIES TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE OVERVIEW -1- SECTION I – BOARD STRUCTURE DEMOGRAPHICS -2- SIZE OF BOARD -3- COMPOSITION OF BOARD -4- AVERAGE AGE OF BOARD -6- LENGTH OF BOARD TERM -7- BOARD MEETINGS PER YEAR -8- BOARD COMMITTEES -9- SECTION II – BOARD COMPENSATION -11- CASH VERSUS EQUITY -12- ANNUAL BOARD RETAINER -13- BOARD AND COMMITTEE MEETING FEES -14- COMMITTEE MEMBER RETAINER AND CHAIRMAN COMPENSATION -15- STOCK OPTION VALUATION METHODOLOGY -16- STOCK OPTION GRANT VALUES -17- STOCK OPTION GRANT SIZES -18- DIRECTOR TOTAL COMPENSATION -19- ADDITIONAL COMPENSATION INFORMATION -20- SUMMARY OF DIRECTOR COMPENSATION BY COMPANY -22- ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Frederiic W.. Cook & Co..,, Inc.. OVERVIEW There are many studies of board compensation at S&P500,, dot..com or Internet companies.. This report is unique in that it presents an analysis of the structure,, demographics and compensation for boards of directors of the companies included in the Nasdaq-100 Index as of July 1,, 2001.. This index has become the universal standard for evaluating the performance of technology companies.. It reflects the Nasdaq’s 100 largest companies across major industry groups.. The information in this report is presented both in summary form and on a company-by-company basis.. All information was taken from company proxy statements,, annual reports,, and 10-K filings for the period July 1,, 2000,, through June 30,, 2001.. In cases where publicly available information was unclear,, direct inquiries were made to the companies.. The first section of the report summarizes the key structural and demographic aspects of a board of directors such as size,, length of term,, number of board meetings,, number of committees,, etc. -

In the United States District Court

Case: 1:13-cv-00537 Document #: 85 Filed: 06/16/14 Page 1 of 11 PageID #:<pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION MAHMOOD ALIZADEH, on behalf of ) himself and all others similarly situated, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) No. 13 C 537 v. ) ) Judge Sara L. Ellis TELLABS, INC., TIMOTHY J. WIGGINS, ) and THOMAS P. MINICHIELLO ) ) Defendants. ) OPINION AND ORDER Lead Plaintiffs Brian Jensen and Alfredo Acosta bring this case on behalf of themselves and a putative class of similarly situated individuals who purchased securities in Tellabs, Inc. (“Tellabs”). Plaintiffs allege that Tellabs and two of its officers, Timothy Wiggins and Thomas Minichiello, made false or misleading representations with regard to Tellabs’ business operations which caused Tellabs’ stock price to be artificially inflated. Specifically, Plaintiffs allege that Defendants misrepresented the viability of Tellabs’ products and failed to promptly disclose that Tellabs had lost the business of its primary customer, AT&T. In doing so, Plaintiffs contend that Defendants violated Sections 10(b) and 20(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, codified as 15 U.S.C. § 78j(b) and t(a), and SEC Rule 10b-5, 17 U.S.C. § 240.10b-5. Now before the Court are Defendants’ motion to dismiss the Amended Complaint for failure to comply with the heightened pleading standards that govern claims for securities fraud. [42] Because Plaintiffs fail to specify which of Defendants’ statements were false or misleading and fail to connect each alleged misstatement with a contrary allegation of fact, the Amended Complaint is dismissed without prejudice. Case: 1:13-cv-00537 Document #: 85 Filed: 06/16/14 Page 2 of 11 PageID #:<pageID> BACKGROUND1 Tellabs designs and develops telecommunications network products, which it sells primarily to telecommunications service providers. -

Cfos of the Largest Public Companies

FOCUS: FINANCE CRAIN’S CHICAGO BUSINESS • FEBRUARY 4, 2008 29 CRAIN’S LIST CFOS OF THE LARGEST PUBLIC COMPANIES Ranked by 2006 revenue 2006 revenue (millions); Name Address % change from Undergraduate Graduate Company Phone/Web site Title(s) previous year Age alma mater alma mater JAMES A. BELL 100 N. Riverside Plaza, Chicago 60606 Executive vice-president of $61,530.0 59 California State Uni- NA 1 Boeing Co. (312) 544-2000; www.boeing.com finance, chief financial officer 14.7% versity at Los Angeles J. MILES REIDY 3333 Beverly Road, Hoffman Estates Executive vice-president, $53,012.0 45 Georgetown University Carnegie Mellon 2 Sears Holdings Corp. 60179; (847) 286-2500 chief financial officer 7.9% University www.searsholdings.com WILLIAM M. RUDOLPHSEN 200 Wilmot Road, Deerfield 60015 Senior vice-president, $47,409.0 52 Marquette University DePaul University 3 Walgreen Co. (847) 940-2500; www.walgreens.com chief financial officer 12.3% Linda THOMAS J. MEREDITH 1303 E. Algonquin Road, Schaumburg Executive vice-president, $42,879.0 57 St. Francis University Georgetown Univer- Imonti 4 Motorola Inc. 60196; (847) 576-5000 acting chief financial officer 21.6% sity; Duquesne Uni- ERIK UNGER www.motorola.com versity School of Law A brave new DAVID B. BURRITT 100 N.E. Adams St., Peoria 61629 Vice-president, $41,517.0 52 Bradley University University of Illinois 5 Caterpillar Inc. (309) 675-1000; www.cat.com chief financial officer 14.2% numbers world The chief financial officer’s role 6 DOUGLAS J. SCHMALZ 4666 E. Faries Pkwy., Decatur 62526 Senior vice-president, $36,596.1 61 University of NA is shifting as companies expand Archer Daniels Midland Co. -

Thurman Ross, Et Al. V. Career Education Corporation, Et Al. 12-CV-00276-Lead Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Points and Authoriti

Case: 1:12-cv-00276 Document #: 111 Filed: 11/04/13 Page 1 of 236 PageID #:2457 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION THURMAN ROSS, by and on behalf of himself and all others similarly situated, Civil Action No. 12 C 276 Plaintiff, Hon. John W. Darrah vs. CAREER EDUCATION CORPORATION, GARY E. McCULLOUGH, and MICHAEL J. GRAHAM, Defendants. LEAD PLAINTIFFS’ MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF UNOPPOSED MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT Jay W. Eisenhofer Joseph F. Rice Geoffrey C. Jarvis James M. Hughes Jeff A. Almeida David P. Abel Christine M. Mackintosh Meghan S. B. Oliver GRANT & EISENHOFER P.A. MOTLEY RICE LLC 123 Justison Street 28 Bridgeside Blvd. Wilmington, DE 19801 Mt. Pleasant, SC 29464 Telephone: (302) 622-7000 Telephone: (843) 216-9000 Facsimile: (302) 622-7100 Facsimile: (843) 216-9450 Co-Lead Counsel for Lead Plaintiffs Co-Lead Counsel for Lead Plaintiffs and Counsel for Thurman Ross Paul E. Slater (ARDC 2630567) James E. Barz (ARDC 6255605) SPERLING & SLATER, P.C. ROBBINS GELLER RUDMAN 55 West Monroe Street & DOWD LLP Suite 3200 200 South Wacker Drive, 31st Floor Chicago, IL 60603 Chicago, IL 60606 Telephone: (312) 641-3200 Telephone: (312) 674-4673 Facsimile: (312) 641-6492 Facsimile: (312) 674-4676 Liaison Counsel for Lead Plaintiffs Additional Counsel for Plaintiffs and Counsel for Thurman Ross Case: 1:12-cv-00276 Document #: 111 Filed: 11/04/13 Page 2 of 236 PageID #:2458 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................1 BACKGROUND.............................................................................................................................3 A. Lead Plaintiffs’ Factual Allegations ....................................................................................3 B. Procedural Posture, Mediation, And Settlement ..................................................................4 C. -

Companies That Hire Felons List

Companies That Hire Felons List HelpForFelons.org AAMCO Transmissions Avon Products Chicago Mercantile Exchange Abbott Laboratories Baskin-Robbins Cintas Ace Hardware Baxter International Circuit City Alamo Rent a Car Best Foods Coldwell Banker Alaska Airlines Best Western Compaq Computer Alberto-Culver BF Goodrich ConAgra Foods Allstate Insurance Black and Decker Dairy Queen Allstate Insurance Blue Cross/Blue Shield DAP Products America West Air Boeing Deer & Co American Airlines Bridgestone/Firestone Del Monte Foods American Express British Airways Dell Corporation American Greetings Budget Rent-A-Car Delta Air Lines Anderson Windows Calvin Klein Delta Faucets AON Computer Campbell Soups Denny’s Inc. Canon USA Dollar Rent A Car Archer Daniel’s Midland Career Education Group Dole Foods ARCO Carrier Domino’s Pizza Arthur J. Gallagher & Co Casio, Inc. Dow Brands AT&T Caterpillar Dunkin Donuts Atlas Van Lines Chase Bank Dunlop Tires Avis Rent-A-Car DuPont Co. McDonalds Sony Duracell Mobil Oil Southwest Air Eddie Bauer Molex Sprint Epson Navistar International Target Equity Office Property Motorola Telephone & Data Systems Exelon New York Times Tellabs Exxon Newsweek Toys R Us Federal Express Niki Tribune Co First Health Group Nisource U.S Cellular Fortune Brands Northern Trust Uneven Investments Fruit of the Loom Old Republic United Airlines Fuji Packaging Corp of America Verizon General Electric PACTIV W.W Grainger General Growth Properties Pepsi-Co Walgreens General Mills Phillip Morris Wal-Mart GMAC R.R Donnelley Wrigley Co Hanes Hosiery Rubbermaid Inc. Zebra Technologies Group Hewitt associates Sara-Lee Zenith Electronics Hilton Hotels Sears & Roebuck Zerox IBM ServiceMaster AirTran Illinois Tool Works Seven Up, Inc. -

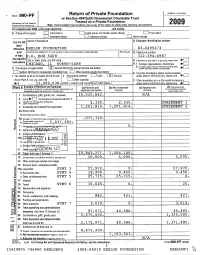

• Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

• Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to u se a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2009, or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that apply Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity Final return Amended return = Address change 0 Name chang e Name of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS label Otherwise , XELON FOUNDATION 83-0499473 print Number and street (or P O box number if man is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype . P.O. BOX 5408 312-394-4987 See Specific City or town , state , and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here Instructions D 1. H ICAGO IL 60680-540 8 Foreign organizations , check here ► p 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, ► H Check typ e of org anization X Section 501 (c )( 3 ) exem t p rivate foundation check here and attach computation foundation Section 4947 (a )( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable p rivate E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method 0 Cash [XI Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, co!. (c), line 16) = Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis ) ► $ 5 3 9 9 9 6 3 8 . -

Ready to Execute Your Strategy?

Consultants who bring clients’ strategic projects to successful completion. Celebrating30 Years Ready to execute your strategy? Getting an organization to agree upon a strategic initiative is difficult. But executing the solution can be equally daunting. Partner with us Perhaps your organization has been tasked with implementing new technology, a Execute complex strategies. merger/acquisition, a divestiture, a regulatory directive or other major initiative. The implementation might be cross-functional, involve multiple integrators, or be • Disparate groups in location transformative. Perhaps the project is high profile or you’re addressing a difficult or ideation or political internal culture. Or maybe your implementation has faced previous • Prior failed attempts at failures. implementation • Enterprise-wide implications Peritius consultants can help. We apply a practical approach to implementing complex strategic initiatives. • Acquisition integration • Turnaround projects We believe the secret to successful strategy execution is to focus on the goals of the strategy. So before we begin the delivery process, we ask questions. What are Enhance your organization’s you trying to accomplish? What problems do you want to solve? And, as in-house delivery skillset. important, how will you know when your strategic goals have been achieved? Your answers to these questions drive our implementation approach. Focus on outcomes Budget wisely Adopt and sustain Peritius defines its approach to project We want you to use your budget We know that early communication execution as Outcome Management. wisely. So we work with you to with stakeholders leads to adoption. That’s because we are laser-focused prioritize the desired outcomes of And adoption leads to organization on delivering the desired outcomes of your strategic initiative. -

Employer Matching Gift Programs Many Corporations, Such As the Ones Listed Below, Give Back to the Communities in Which They Do Business

Employer Matching Gift Programs Many corporations, such as the ones listed below, give back to the communities in which they do business. Many offer matching gift programs, whereby they match the contributions of their employers to charitable organizations. If your employer is listed here, inquire if it offers a matching gift program, which can increase your contribution to Camp Encourage. A.G. Edwards, Inc. Blockbuster, Inc. Fannie Mae Fdn. Abbott Laboratories Blount, Inc. First Banks, Inc. Access Group, The Blue Bell, Inc. First Data Corp. ACE Group BlueLinx Corp. First Horizon National ACF Industries BNSF FMC Corp. Aetna, Inc, Bonneville International. Ford Fdn, Agriliance, LLC Bowater, Inc. Fru-Con Corporation AIG American General BP Furniture Brands International, Inc. Allegro Micro Systems, Brandywine Realty Trust Gap, Inc. Alliant Techsystems Brinks Co., The Gartner Group, Inc. AMC Entertainment, Inc. Brown Shoe Co., Inc. GATX Corp. Ameren Corporation BTG GEICO Corp. America, Inc. Bunge North America, GenAmerica Financial Corporation American Century Companies, Inc. Burns & McDonnell Genentech, Inc. American Express Co. Butler Manufacturing Co. Genesco, Inc. American Honda Motor C. R. Bard. Inc. Georgia Pacific Corp. Amgen, Inc. Cebridge Connections GlaxoSmithKline AMSTED Industries Ana log CIGNA Corp. Google, Inc. Andrews McMeel Cingular Wireless Grainger Andrews McMeel Universal (AMU) Citigroup Graybar Electric Company, Inc. Anheuser-Busch Companies, Inc. CNA Great-West Life AON Corp. Coca-Cola Co. Green Mountain Coffee Roasters Apache Corp. Colgate-Palmolive Co. Guth Lighting Systems, Inc. Aquila, Inc. Commerce Bancshares, Inc. H&R Block, Inc. Arch Coal, Inc. Computer Associates Hallmark Cards, Inc. Art Technology Group, Costco Wholesale Corp. Harcourt, Inc.