The Wise Thing Is Not Wisdom’ : TERRANOVA 49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Thebaid Europa, Cadmus and the Birth of Dionysus

The Thebaid Europa, Cadmus and the birth of Dionysus Caesar van Everdingen. Rape of Europa. 1650 Zeus = Io Memphis = Epaphus Poseidon = Libya Lysianassa Belus Agenor = Telephassa In the Danaid, we followed the descendants of Belus. The Thebaid follows the descendants of Agenor Agenor = Telephassa Cadmus Phoenix Cylix Thasus Phineus Europa • Agenor migrated to the Levant and founded Sidon • But see Josephus, Jewish Antiquities i.130 - 139 • “… for Syria borders on Egypt, and the Phoenicians, to whom Sidon belongs, dwell in Syria.” (Hdt. ii.116.6) The Levant Levant • Jericho (9000 BC) • Damascus (8000) • Biblos (7000) • Sidon (4000) Biblos Damascus Sidon Tyre Jericho Levant • Canaanites: • Aramaeans • Language, not race. • Moved to the Levant ca. 1400-1200 BC • Phoenician = • purple dye people Biblos Damascus Sidon Tyre Agenor = Telephassa Cadmus Phoenix Cylix Thasus Phineus Europa • Zeus appeared to Europa as a bull and carried her to Crete. • Agenor sent his sons in search of Europa • Don’t come home without her! • The Rape of Europa • Maren de Vos • 1590 Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (Spain) Image courtesy of wikimedia • Rape of Europa • Caesar van Everdingen • 1650 • Image courtesy of wikimedia • Europe Group • Albert Memorial • London, 1872. • A memorial for Albert, husband of Queen Victoria. Crete Europa = Zeus Minos Sarpedon Rhadamanthus • Asterius, king of Crete, married Europa • Minos became king of Crete • Sarpedon king of Lycia • Rhadamanthus king of Boeotia The Brothers of Europa • Phoenix • Remained in Phoenicia • Cylix • Founded -

Thebaid 2: Oedipus Descendants of Cadmus

Thebaid 2: Oedipus Descendants of Cadmus Cadmus = Harmonia Aristaeus = Autonoe Ino Semele Agave = Echion Pentheus Actaeon Polydorus (?) Autonoe = Aristaeus Actaeon Polydorus (?) • Aristaeus • Son of Apollo and Cyrene • Actaeon • While hunting he saw Artemis bathing • Artemis set his own hounds on him • Polydorus • Either brother or son of Autonoe • King of Cadmeia after Pentheus • Jean-Baptiste-Camile Corot ca. 1850 Giuseppe Cesari, ca. 1600 House of Cadmus Hyrieus Cadmus = Harmonia Dirce = Lycus Nycteus Autonoe = Aristaeus Zeus = Antiope Nycteis = Polydorus Zethus Amphion Labdacus Laius Tragedy of Antiope • Polydorus: • king of Thebes after Pentheus • m. Nycteis, sister of Antiope • Polydorus died before Labdacus was of age. • Labdacus • Child king after Polydorus • Regency of Nycteus, Lycus Thebes • Laius • Child king as well… second regency of Lycus • Zethus and Amphion • Sons of Antiope by Zeus • Jealousy of Dirce • Antiope imprisoned • Zethus and Amphion raised by shepherds Zethus and Amphion • Returned to Thebes: • Killed Lycus • Tied Dirce to a wild bull • Fortified the city • Renamed it Thebes • Zethus and his family died of illness Death of Dirce • The Farnese Bull • 2nd cent. BC • Asinius Pollio, owner • 1546: • Baths of Caracalla • Cardinal Farnese • Pope Paul III Farnese Bull Amphion • Taught the lyre by Hermes • First to establish an altar to Hermes • Married Niobe, daughter of Tantalus • They had six sons and six daughters • Boasted she was better than Leto • Apollo and Artemis slew every child • Amphion died of a broken heart Niobe Jacques Louis David, 1775 Cadmus = Harmonia Aristeus =Autonoe Ino Semele Agave = Echion Nycteis = Polydorus Pentheus Labdacus Menoecius Laius = Iocaste Creon Oedipus Laius • Laius and Iocaste • Childless, asked Delphi for advice: • “Lord of Thebes famous for horses, do not sow a furrow of children against the will of the gods; for if you beget a son, that child will kill you, [20] and all your house shall wade through blood.” (Euripides Phoenissae) • Accidentally, they had a son anyway. -

Homer the Iliad

1 Homer The Iliad Translated by Ian Johnston Open access: http://johnstoniatexts.x10host.com/homer/iliadtofc.html 2010 [Selections] CONTENTS I THE QUARREL BY THE SHIPS 2 II AGAMEMNON'S DREAM AND THE CATALOGUE OF SHIPS 5 III PARIS, MENELAUS, AND HELEN 6 IV THE ARMIES CLASH 6 V DIOMEDES GOES TO BATTLE 6 VI HECTOR AND ANDROMACHE 6 VII HECTOR AND AJAX 6 VIII THE TROJANS HAVE SUCCESS 6 IX PEACE OFFERINGS TO ACHILLES 6 X A NIGHT RAID 10 XI THE ACHAEANS FACE DISASTER 10 XII THE FIGHT AT THE BARRICADE 11 XIII THE TROJANS ATTACK THE SHIPS 11 XIV ZEUS DECEIVED 11 XV THE BATTLE AT THE SHIPS 11 XVI PATROCLUS FIGHTS AND DIES 11 XVII THE FIGHT OVER PATROCLUS 12 XVIII THE ARMS OF ACHILLES 12 XIX ACHILLES AND AGAMEMNON 16 XX ACHILLES RETURNS TO BATTLE 16 XXI ACHILLES FIGHTS THE RIVER 17 XXII THE DEATH OF HECTOR 17 XXIII THE FUNERAL GAMES FOR PATROCLUS 20 XXIV ACHILLES AND PRIAM 20 I THE QUARREL BY THE SHIPS [The invocation to the Muse; Agamemnon insults Apollo; Apollo sends the plague onto the army; the quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon; Calchas indicates what must be done to appease Apollo; Agamemnon takes Briseis from Achilles; Achilles prays to Thetis for revenge; Achilles meets Thetis; Chryseis is returned to her father; Thetis visits Zeus; the gods con-verse about the matter on Olympus; the banquet of the gods] Sing, Goddess, sing of the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus— that murderous anger which condemned Achaeans to countless agonies and threw many warrior souls deep into Hades, leaving their dead bodies carrion food for dogs and birds— all in fulfilment of the will of Zeus. -

Euripides and Gender: the Difference the Fragments Make

Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Ruby Blondell, Chair Deborah Kamen Olga Levaniouk Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2013 Melissa Karen Anne Funke University of Washington Abstract Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Ruby Blondell Department of Classics Research on gender in Greek tragedy has traditionally focused on the extant plays, with only sporadic recourse to discussion of the many fragmentary plays for which we have evidence. This project aims to perform an extensive study of the sixty-two fragmentary plays of Euripides in order to provide a picture of his presentation of gender that is as full as possible. Beginning with an overview of the history of the collection and transmission of the fragments and an introduction to the study of gender in tragedy and Euripides’ extant plays, this project takes up the contexts in which the fragments are found and the supplementary information on plot and character (known as testimonia) as a guide in its analysis of the fragments themselves. These contexts include the fifth- century CE anthology of Stobaeus, who preserved over one third of Euripides’ fragments, and other late antique sources such as Clement’s Miscellanies, Plutarch’s Moralia, and Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae. The sections on testimonia investigate sources ranging from the mythographers Hyginus and Apollodorus to Apulian pottery to a group of papyrus hypotheses known as the “Tales from Euripides”, with a special focus on plot-type, especially the rape-and-recognition and Potiphar’s wife storylines. -

The Legend of Cadmus and the Logographi Author(S): A

The Legend of Cadmus and the Logographi Author(s): A. W. Gomme Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 33 (1913), pp. 53-72 Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/624086 . Accessed: 17/01/2015 11:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Hellenic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sat, 17 Jan 2015 11:11:03 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE LEGENDIOF CADMUS AND THE LOGOGRAPHI. I. 1.-FIRST APPEARANCE OF THE PHOENICIAN THEORY. IN an article in the Annual of the British School at Athens 1 I have endeavoured to show that the geography of Boeotia lends no support to the theory that the Cadmeans were Phoenicians. Yet from the fifth century onwards at least, there was a firmly established and, as far as we know, universally accepted tradition that they were-a tradition indeed lightly put aside by most modern scholars as unimportant. -

The Bacchae of Euripides

The Bacchae of Euripides By Wole Soyinka Directed by Prof. Judyie Al-Bilali Dramaturgy by Prof. Megan Lewis STUDY GUIDE Contact: Prof Megan Lewis [email protected] DIRECTOR’S NOTE Dionysus and his magnificent initiates, the Bacchantes, have come back for me. I met them twenty years ago when I directed this same adaptation by distinguished Nigerian Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka. I embraced his vision as it foregrounds the social and political transformations inherent to the ancient drama, and now two decades later, Soyinka’s script rings even more true as we face unprecedented environmental, ecological, and spiritual challenges. A play is relevant after 2,400 years because it illuminates primal forces, notable among them, sexuality. Dionysus, called by many names including ‘The Liberator’ has often symbolized gender fluidity. In the rigid caste system of ancient Greece, his devotees included slaves, women, and foreigners -- allowing those usually excluded to participate in the annual Dionysian festivals. Our play is set in 2020, just across the threshold into the upcoming decade, at the pivot point of a new era in human history. Our location is Gaia, the mythological Greek name recognizing our beloved and beleaguered planet Earth as a sentient, living goddess. Right now, Gaia demands our attention. She calls us beyond ideology to unity, a call we must heed for our survival as a species. Myth is how we navigate and ultimately evolve both individual and collective psyches. Myth must change for us to grow. Artists are the antennae for society and we are re-imagining Euripides’ myth of Dionysus to address our need for balance between reason and passion. -

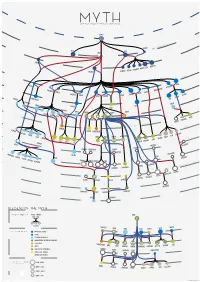

Legend of the Myth

MYTH Graph of greek mythological figures CHAOS s tie dei ial ord EREBUS rim p EROS NYX GAEA PONTU S ESIS NEM S CER S MORO THANATO A AETHER HEMER URANUS NS TA TI EA TH ON PERI IAPE HY TUS YNE EMNOS MN OC EMIS EANUS US TH TETHYS COE LENE PHOEBE SE EURYBIA DIONE IOS CREUS RHEA CRONOS HEL S EO PR NER OMETH EUS EUS ERSE THA P UMAS LETO DORIS PAL METIS LAS ERIS ST YX INACHU S S HADE MELIA POSEIDON ZEUS HESTIA HERA P SE LEIONE CE A G ELECTR CIR OD A STYX AE S & N SIPH ym p PA hs DEMETER RSES PE NS MP IA OLY WELVE S EON - T USE OD EKATH M D CHAR ON ARION CLYM PERSEPHONE IOPE NE CALL GALA CLIO TEA RODITE ALIA PROTO RES ATHENA APH IA TH AG HEBE A URAN AVE A DIKE MPHITRIT TEMIS E IRIS OLLO AR BIA AP NIKE US A IO S OEAGR ETHRA THESTIU ATLA S IUS ACRIS NE AGENOR TELEPHASSA CYRE REUS TYNDA T DA AM RITON LE PHEUS BROS OR IA E UDORA MAIA PH S YTO PHOEN OD ERYTHE IX EUROPA ROMULUS REMUS MIG A HESP D E ERIA EMENE NS & ALC UMA DANAE H HARMONIA DIOMEDES ASTOR US C MENELA N HELE ACLES US HER PERSE EMELE DRYOPE HERMES MINOS S E ERMION H DIONYSUS SYMAETHIS PAN ARIADNE ACIS LATRAMYS LEGEND OF THE MYTH ZEUS FAMILY IN THE MYTH FATHER MOTHER Zeus IS THEM CHILDREN DEMETER LETO HERA MAIA DIONE SEMELE COLORS IN THE MYTH PRIMORDIAL DEITIES TITANS SEA GODS AND NYMPHS DODEKATHEON, THE TWELVE OLYMPIANS DIKE OTHER GODS PERSEPHONE LO ARTEMIS HEBE ARES HERMES ATHENA APHRODITE DIONYSUS APOL MUSES EUROPA OSYNE GODS OF THE UNDERWORLD DANAE ALCEMENE LEDA MNEM ANIMALS AND HYBRIDS HUMANS AND DEMIGODS circles in the myth 196 M - 8690 K } {Google results M CALLIOPE INOS PERSEU THALIA CLIO 8690 K - 2740 K S HERACLES HELEN URANIA 2740 K - 1080 K 1080 K - 2410 J. -

Introduction to the Bacchae

Introduction to the Bacchae • Let me begin by saying that I have been assigned to perform an impossible task. I have been given just a few minutes to introduce the play. In other words, this means that in the next five or ten minutes I will attempt the impossible: • To place The Bacchae in the context of Euripides’ work • To place Euripides in the context of Greek Tragedy • To place Greek and Euripidean Tragedy in the context of Greek and Athenian History • To place all of the above in the context of the present, and explain why all these are important for us right here, right now both personally and collectively. • So let me begin: • Euripides, together with Aeschylus and Sophocles, was one of the three most famous and influential Greek Tragedians in the fifth century BC Athens, the golden age of Greek Drama. But of the three, Euripides is the most modern, the most revolutionary, the one who was most popular with the people (Sicilian Expedition) in spite of the fact that he received fewer awards by the judges, the one whose more plays survived, the most tragic according to Aristotle, the most innovative, the most philosophical, and MY most beloved Athenian Playwright with whom (by my own admission) I have spent a considerable amount of my life, INTIMATELY…. • The Bacchae is one of Euripides’ most profound plays, one of the most powerful plays ever written, and it was presented for the first time in ancient Athens shortly after the poet’s death in 406 B.C. However, its meaning and ideas remain most relevant today, particularly in front of the troublesome issues that challenge our humanity in the present, both personally and collectively. -

Gods, Heroes, Magic, and Mysteries: Religion in Ancient Greece

Anthropology/Religion 225 Gods, Heroes, Magic, and Mysteries: Religion in Ancient Greece Bates College -- Winter, 1996 Robert W. Allison and Loring M. Danforth Infrastructure How This Electronic Syllabus Works This syllabus is enriched with links to the Perseus Project's World Wide Web site. Look up the Perseus editions of the required readings. The Perseus versions are equipped with helps linked to highlighted key words in the readings. Some of these highlighted terms connect you instantly to on-line encyclopedia entries, while others lead you to what other ancient authors have said about the same subject. You can follow these leads where ever your own personal curiosity might lead you, and to find information on any subject which you might like to pursue as a research paper topic. Electronic resources also allow you to cut and paste quotations and illustrations from the text directly into your research papers as you draft them on your word processor. (Don't forget your responsibilities for citing sources and giving credit when you do this!) For an introduction to Perseus and for on line help using it, take a look at Perseus at Bates. Course Objectives The present course is a study of ancient Greek religion from both a historical and an anthropological perspective. It follows a broadly historical outline and covers these important topics and periods: Religion in Minoan and Mycenaean Culture (the bronze age on Crete and in the Aegean basin: ca. 2700-1100 B.C.E.) Religion in the "Heroic Age" as reflected in Homer and Hesiod (the bronze age on the mainland of Greece: ca. -

The Bacchae by EURIPIDES Translation by AARON POOCHIGIAN Created and Performed by SITI COMPANY Theater Latté Da’S Re-Imagined Staging of the Beloved Opera Returns

McGuire Proscenium Stage / Feb 29 – April 5, 2020 The Guthrie Theater presents a SITI Company production of The Bacchae by EURIPIDES translation by AARON POOCHIGIAN created and performed by SITI COMPANY Theater Latté Da’s re-imagined staging of the beloved opera returns. Painting: Bonjour Tristesse, Nicholas Harper LA BOHÈME MUSIC BY GIACOMO PUCCINI LIBRETTO BY LUIGI ILLICA AND GUISEPPE GIACOSA NEW ORCHESTRATION BY JOSEPH SCHLEFKE DIRECTED BY PETER ROTHSTEIN MUSIC DIRECTION BY ERIC MCENANEY MAR 11 - APR 26, 2020 • RITZ THEATER • TICKETS ON SALE NOW! Inside IN PICTURES An Iraqi Feast • 4 WELCOME From Artistic Director Joseph Haj • 5 GUTHRIE SPOTLIGHT A Timeline of Greek Tragedy • 8 GUTHRIE SPOTLIGHT Greeks at the Guthrie • 8 THE BACCHAE Cast and Creative Team • 11 Biographies • 12 PLAY FEATURES About SITI Company • 17 A Q&A With Director Anne Bogart • 18 The Dangerous Liberation of Theater • 20 PLAY FEATURE Backstory • 22 From the Director • 18 SUPPORTERS Annual Fund Contributors • 24 Corporate, Foundation and Public Support • 27 PLAY FEATURE Why Euripides Wrote The WHO WE ARE Bacchae • 20 Board of Directors and Guthrie Staff •28 GOOD TO KNOW Theater Information and Policies • 30 Guthrie Theater Program Volume 57, Issue 6 • Copyright 2020 818 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis, MN 55415 ADMINISTRATION 612.225.6000 EDITOR Johanna Buch BOX OFFICE 612.377.2224 or 1.877.44.STAGE (toll-free) GRAPHIC DESIGNER Brian Bressler guthrietheater.org • Joseph Haj, artistic director CONTRIBUTORS Anne Bogart, Helene Foley, Joseph Haj. Special thanks to SITI Company. The Guthrie creates transformative theater experiences that ignite the The Guthrie program is published by the Guthrie Theater. -

![[PDF]The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7259/pdf-the-myths-and-legends-of-ancient-greece-and-rome-4397259.webp)

[PDF]The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome

The Myths & Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome E. M. Berens p q xMetaLibriy Copyright c 2009 MetaLibri Text in public domain. Some rights reserved. Please note that although the text of this ebook is in the public domain, this pdf edition is a copyrighted publication. Downloading of this book for private use and official government purposes is permitted and encouraged. Commercial use is protected by international copyright. Reprinting and electronic or other means of reproduction of this ebook or any part thereof requires the authorization of the publisher. Please cite as: Berens, E.M. The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome. (Ed. S.M.Soares). MetaLibri, October 13, 2009, v1.0p. MetaLibri http://metalibri.wikidot.com [email protected] Amsterdam October 13, 2009 Contents List of Figures .................................... viii Preface .......................................... xi Part I. — MYTHS Introduction ....................................... 2 FIRST DYNASTY — ORIGIN OF THE WORLD Uranus and G (Clus and Terra)........................ 5 SECOND DYNASTY Cronus (Saturn).................................... 8 Rhea (Ops)....................................... 11 Division of the World ................................ 12 Theories as to the Origin of Man ......................... 13 THIRD DYNASTY — OLYMPIAN DIVINITIES ZEUS (Jupiter).................................... 17 Hera (Juno)...................................... 27 Pallas-Athene (Minerva).............................. 32 Themis .......................................... 37 Hestia -

Bulfinch's Mythology the Age of Fable by Thomas Bulfinch

1 BULFINCH'S MYTHOLOGY THE AGE OF FABLE BY THOMAS BULFINCH Table of Contents PUBLISHERS' PREFACE ........................................................................................................................... 3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 7 ROMAN DIVINITIES ............................................................................................................................ 16 PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA ............................................................................................................ 18 APOLLO AND DAPHNE--PYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS ............................ 24 JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTO--DIANA AND ACTAEON--LATONA AND THE RUSTICS .................................................................................................................................................... 32 PHAETON .................................................................................................................................................. 41 MIDAS--BAUCIS AND PHILEMON ....................................................................................................... 48 PROSERPINE--GLAUCUS AND SCYLLA ............................................................................................. 53 PYGMALION--DRYOPE-VENUS