Experimental Evidence from South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010

Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010 Julian A Jacobs (8805469) University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Prof Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie Masters Research Essay in partial fulfillment of Masters of Arts Degree in History November 2010 DECLARATION I declare that „Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010‟ is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. …………………………………… Julian Anthony Jacobs i ABSTRACT This is a study of activists from Manenberg, a township on the Cape Flats, Cape Town, South Africa and how they went about bringing change. It seeks to answer the question, how has activism changed in post-apartheid Manenberg as compared to the 1980s? The study analysed the politics of resistance in Manenberg placing it within the over arching mass defiance campaign in Greater Cape Town at the time and comparing the strategies used to mobilize residents in Manenberg in the 1980s to strategies used in the period of the 2000s. The thesis also focused on several key figures in Manenberg with a view to understanding what local conditions inspired them to activism. The use of biographies brought about a synoptic view into activists lives, their living conditions, their experiences of the apartheid regime, their brutal experience of apartheid and their resistance and strength against a system that was prepared to keep people on the outside. This study found that local living conditions motivated activism and became grounds for mobilising residents to make Manenberg a site of resistance. It was easy to mobilise residents on issues around rent increases, lack of resources, infrastructure and proper housing. -

Clinics in City of Cape Town

Your Time is NOW. Did the lockdown make it hard for you to get your HIV or any other chronic illness treatment? We understand that it may have been difficult for you to visit your nearest Clinic to get your treatment. The good news is, your local Clinic is operating fully and is eager to welcome you back. Make 2021 the year of good health by getting back onto your treatment today and live a healthy life. It’s that easy. Your Health is in your hands. Our Clinic staff will not turn you away even if you come without an appointment. Speak to us Today! @staystrongandhealthyza City of Cape Town Metro Health facilities Eastern Sub District , Area East, KESS Clinic Name Physical Address Contact Number City Ikhwezi CDC Simon Street, Lwandle, 7140 021 444 4748/49/ Siyenza 51/47 City Dr Ivan Toms O Nqubelani Street, Mfuleni, Cape Town, 021 400 3600 Siyenza CDC 7100 Metro Mfuleni CDC Church Street, Mfuleni 021 350 0801/2 Siyenza Metro Helderberg c/o Lourensford and Hospital Roads, 021 850 4700/4/5 Hospital Somerset West, 7130 City Eerste River Humbolt Avenue, Perm Gardens, Eerste 021 902 8000 Hospital River, 7100 Metro Nomzamo CDC Cnr Solomon & Nombula Street, 074 199 8834 Nomzamo, 7140 Metro Kleinvlei CDC Corner Melkbos & Albert Philander Street, 021 904 3421/4410 Phuthuma Kleinvlei, 7100 City Wesbank Clinic Silversands Main Street Cape Town 7100 021 400 5271/3/4 Metro Gustrouw CDC Hassan Khan Avenue, Strand 021 845 8384/8409 City Eerste River Clinic Corner Bobs Way & Beverly Street, Eeste 021 444 7144 River, 7100 Metro Macassar CDC c/o Hospital -

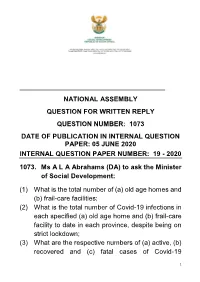

1073 Date of Publication in Internal Question Paper: 05 June 2020 Internal Question Paper Number: 19 - 2020 1073

_______________________________________ NATIONAL ASSEMBLY QUESTION FOR WRITTEN REPLY QUESTION NUMBER: 1073 DATE OF PUBLICATION IN INTERNAL QUESTION PAPER: 05 JUNE 2020 INTERNAL QUESTION PAPER NUMBER: 19 - 2020 1073. Ms A L A Abrahams (DA) to ask the Minister of Social Development: (1) What is the total number of (a) old age homes and (b) frail-care facilities; (2) What is the total number of Covid-19 infections in each specified (a) old age home and (b) frail-care facility to date in each province, despite being on strict lockdown; (3) What are the respective numbers of (a) active, (b) recovered and (c) fatal cases of Covid-19 1 infections in the specified facilities in each province; (4) How does her department intend to isolate the infected persons and prevent any further infections in the old age homes and frail-care facilities? NW1368E REPLY: (1) (a) There are currently 418 Residential facilities (old age homes) spread nationally as follows: NAME OF THE NO. OF PROVINCE FACILITIES North West 28 Gauteng 76 Limpopo 8 Free State 49 Western Cape 120 Mpumalanga 21 KZN 41 Northern Cape 26 Eastern Cape 49 Total 418 2 (1) (b) Frail- care facilities: In terms of the Older Persons Act No. 13 of 2006, Old Age Homes are Frail-Care Facilities. The name used is “residential facility”. The Older Persons Act, 2006 mandates that Older Persons should remain in their communities within their families for as long as possible. Institutional care should be the last resort or the last stage of Social Work intervention, i.e. the continuum of care. -

Cape Town Rd R L N W Or T

Legend yS Radisson SAS 4 C.P.U.T. u# D S (Granger Bay Campus) H R u Non-Perennial River r Freeway / National Road R C P A r E !z E l e T Mouille Point o B . Granger Bay ast y A t Perennial River h B P l Village E Yacht Club e Through Route &v e A d ie x u# s Granger r a Ü C R P M R a H nt n d H . r l . R y hN a e d y d u# Ba G Bay L i % Railway with Station r R ra r P E P The Table Minor Road a D n te st a Table Bay Harbour l g a a 7 La Splendina . e s N R r B w Bay E y t ay MetropolitanO a ak a P Water 24 R110 Route Markers K han W y re u i n1 à î d ie J Step Rd B r: u# e R w Q r ie Kings Victoria J Park / Sports Ground y t W 8} e a L GREEN POINT Wharf 6 tt B a. Fort Wynyard Warehouse y y Victoria Built-up Area H St BMW a E K J Green Point STADIUM r 2 Retail Area Uà ge Theatre Pavillion r: 5 u lb Rd an y Q Basin o K Common Gr @ The |5 J w Industrial Area Pavillion!C Waterfront ua e Service Station B Greenpoint tt çc i F Green Point ~; Q y V & A WATERFRONT Three Anchor Bay ll F r: d P ri o /z 1 R /z Hospital / Clinic with Casualty e t r CHC Red Shed ÑG t z t MARINA m u# Hotel e H d S Cape W Somerset Quay 4 r r y Craft A s R o n 1x D i 8} n y th z Hospital / Clinic le n Medical a Hospital Warehouse u 0 r r ty m Green Point Club . -

CITY CENTRE MAP MOUILLE POINT TABLE BAY Visitor Information Centres Police Station MOUILLE POINT Beach Surrey Granger Bay LIGHTHOUSE Hospital Rothesay Bay

Cape Town Tourism CITY CENTRE MAP MOUILLE POINT TABLE BAY Visitor Information Centres Police Station MOUILLE POINT Beach Surrey Granger Bay LIGHTHOUSE Hospital Rothesay Bay Kiewietlaan Metropolitan Places of Interest Fritz Sonnenberg Fritz Golf Course Haul Metropolitan Stephans Way FORT WYNYARD East pier Golf Course Blue Flag Status Beaches CAPE TOWN East pier Bay Rugby STADIUM Park BreakwaterVICTORIA WHARF Cricket GREEN POINT Oval Beach SHOPPING CENTRE URBAN PARK City Sightseeing Bus Routes THREE Sea Point Rugby Police Station V&A WATERFRONT Stanley Red City Tour Blvd Vlei Athletics ay Somerset ANCHOR BAY Bill Peters Drive er B Tennis Green Track ng ra Precinct Health and Point G Blue Mini Peninsula Tour Fitness Park FERRY TO Sea Point ROBBEN ISLAND ROCKLANDS BEACH South Arm Penarth Civic Centre Helen Suzman Blvd Green Point and Clinic Track Both Routes Fort ZEITZ MOCAA Grove Main Wigtown Richmond MyCiti Glengariff Hill Marine Pine Portswood SEA POINT PROMENADE STADIUM TWO OCEANS Beach Rd Avondale Yellow Downtown Tour St. Bede’s St. Ravenscraig AQUARIUM Rocklands Leicester Clydebank St. Georges St. Sydney STATION Varney’s Main Norman Fish Quay Camberwell Antrim York Hateld Scholtz Dysart Croxteth WATERSHED South Arm TO CAMPS BAY St. JamesStone Torbay Dock Grimsby Clyde Transport Information Centre Romney Braeside Haytor LeinsterAshstead Exhibition West Quay Norfolk Frere Sollum Cheviot +27 (0)800 656 463 Wisbeach Main ath ATLANTIC OCEAN Mutley he Modena Cavalcade ck High Level la Thornhill Hall Hofmeyr B Kort Joubert Rhine Glengariff -

Cape Town Ward Councilors

CAPE TOWN WARD COUNCILORS Sub Council 1 Ward Councillors Tel;Mobile; fax Suburbs Century City; Marconi Beam; Milnerton Ridge; Montague Gardens; Phoenix; Rietvlei Table View; Sunset Beach; Sunridge; Killarney Gardens; Tel/Fax: 021 550 - 1028 Mobile: Milnerton, Flamingo Vlei; Sunset Links; Joe Slovo Blaauwberg 4 Berry Liz 082 422 1233 Park; Royal Ascot Melkbosstrand; Duynefontein; Van Riebeeckstrand; Atlantic Beach Estate; Bloubergstrand; West Tel: 021 400 - 1306 Fax: Beach; Bloubergrant; Blouberg Rise; Blouberg 021 400 - 1263 Mobile:083 306 Sands; Sunningdale; Klein Zoute Rivier; Peter Deacon 23 Ina Neilson 6730 Morningstar; Vissershok; Frankdale Tygerhof; Sanddrift; Woodbridge Island; Milnerton Cenral Metro Industrial; Ysterplaat; Rugby; Paarden Eiland; Woodstock; Brooklyn; Salt River; Ysterplaat Air Base; Lagoon Beach; Milnerton Golf Course; Maitland; West dise of Residential area od Century Tel:(021)550 - 1001 55 Bernadette Le Roux Mobile: 084 455 5732 City; Waterfront area; Sunset links Te/Fax: 021 593 - 5802 Mobile: Summer Greens; Arcacia Park; Wingfield; 56 Jack Ridder 076 618 1496 Fractreton; Kensington; Windermere Belgravia; Bellair; Bloemhof; Blommendal; Blomtuin; Bo Oakdale; Chrismar; Groenvallei; Heemstede; Joubert Park; Stellenridge; Stikland Tel: 021 903 3289 Fax:021 Hospitaal; Stikland Industrial Area; Thalman; 906 - 1192 Mobile: 083 591 Vredenberg; Stikland; La Belle; Vredenberg; De La Sub Council 2 3 Ewald Groenewald 6578 Hey Brackenfell Industrial; Everite Industria; Protea Heights;(north protea & keurboom street); Ruwari; -

Privatisation of Urban Public Space

THE ‘SILENT’ PRIVATISATION OF URBAN PUBLIC SPACE IN CAPE TOWN, 1975 – 2004 Manfred Aldrin Spocter A mini-thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA in the Faculty of Arts, University of the Western Cape November 2005 Supervisor: Associate Professor Ronnie Donaldson KEY WORDS 1. Closure 2. Privatisation 3. Urban public space 4. Micro-privatisation 5. Citizen-driven 6. Cape Town 7. Gated communities 8. Post-apartheid 9. Spatial exclusion 10. Postmodernism i ABSTRACT The ‘Silent’ Privatisation of Urban Public Space in Cape Town, 1975 - 2004 South African cities were subjected to artificial, unnatural growth patterns brought about by apartheid planning that legitimated exclusionary practices in the city and which created and maintained racial, social and class differences between people. Post-apartheid South Africa has witnessed processes of urban fortification, barricading and the gating of urban space that are manifested in contemporary urban South Africa. This research shows that the privatisation of urban public space is not solely a post- apartheid phenomenon. Closure legislation has been, and still is, used by citizens to remove urban space from the public realm through its privatisation. Closures are largely citizen-driven, either individually or as a collective, and it is small public spaces that are privatised, hence the micro-privatisation of public space that could influence the immediate surroundings and erf-sized living space of individuals. The concerns voiced by closure applicants through their application for closure, reflect personal living space concerns. It is ordinary people, not major real estate companies or corporations that are able to influence the land management processes of the city. -

Parker Cottage's Walking Tour of Central Cape Town

Parker Cottage’s Walking Tour of Central Cape Town The City Bowl in Cape Town is a truly wondrous thing. Unlike many colonial city centres, it has a distinct lack of the ubiquitous Western chain stores and manages in large part to retain several tiny and very specialized shops, eateries, galleries, theatres, hotels and bars that would simply not survive in a pressured rental environment in a modern industrialized city. NB. Please take a look at the back page for some important notes before you go on this tour. This tour takes you to: 09h15 Kloof Street – vibey heart of Gardens and the ‘let’s do lunch’ crowd. 09h30 The Long Street Baths – historic Turkish baths and pool 09h45 The Company’s Garden – superb, ornate, city centre park. 10h15 St. George’s Cathedral – Tutu’s centre of resilience. 10h15 The Slave Lodge – how Cape Town and its people came to be 11h00 The District Six Museum – an inspirational piece of history 11h30 Greenmarket Square – bustling African craft market 12h00 Long Street – the ‘anything goes’ street from dawn till dusk (and dusk till dawn) 12h30 The Bo Kaap – the cultural home of the Cape Malay community 13h00 The Waterkant – design and chic abound in this gay friendly quarter 13h30 The Waterfront – love it or hate it, Cape Town’s answer to Sydney harbour Take a cab home to Parker Cottage. Parker Cottage 1 Tel +27 (21)424-6445 | Fax +27 (0)21 424-0195 | Cell +27 (0)79 980 1113 1 & 3 Carstens Street, Tamboerskloof, Cape Town, South Africa [email protected] | www.parkercottage.co.za 09h00 Leave Parker Cottage by turning left out of the gate. -

PENINSULA MAP Police Station WITSAND

MAMRE PELLA ATLANTIS Cape Town Tourism Visitor Information Centres PENINSULA MAP Police Station WITSAND R27 Transport Information Centre 0800 656 463 CAPE TOWN TOURISM SERVICES Champagne GENERAL TRAVEL INFORMATION: All you need to know about Cape Town P hila W d el Adam Tas e ph and travelling within the City. s i t a C Wellington o a R302 s R304 PHILADELPHIA t k M c KOEBERG e RESERVATIONS: You can do all your bookings via Cape Town Tourism a e l b m e i e R s Visitor Information Centres, online and via our Call Centre. b n u a r V y n y a r J u Silwerstroom b s R304 e SANPARKS BOOKINGS/SERVICES: Reservations, Activity Cards, Green Main Beach lm a M Cards & Permits at designated Visitor Information Centres. d l DUYNEFONTEIN O R45 COMPUTICKET BOOKINGS: Book your Theatre, Events or Music Shows R312 at designated Visitor Information Centres. M19 Melkbosstrand N7 MELKBOSSTRAND R44 Langenh WEBTICKETS ONLINE BOOKINGS: Robben Island Trips, Kirstenbosch oven Concerts, Table Mountain Cable Car Trip at all Cape Town Tourism R304 PAARL M14 Visitor Information Centres. Suid Agter Paarl R302 R27 M58 CITY SIGHTSEEING HOP ON HOP OFF BUS TICKETS: Purchase your tickets Main Otto Du Plessis West Coast at designated Visitor Information Centres. l BLAAUWBERG e Lichtenberg w u e h p li V Adderley isser K MYCITI BUS ROUTE SERVICE: Purchase and load your MyConnect Card shok N1 Big Bay at Cape Town International Airport and City Centre. Big Bay BLOUBERGSTRAND i le v West Coast M48 s on Marine m Si PARKLANDS m a Wellington ROBBEN ISLAND d ts o R302 KLAPMUTS P -

P a T R I M O I N E C O N C E P

South African Heritage Resource Agency 11 Harrington Street Zonnebloem Cape Town Friday, 12 June 2020 Dear Interested and Affected Party REQUEST FOR COMMENT: ALTERATIONS & ADDITIONS TO EXISTING DWELLING ERF 10046, 58 LYMINGTON STREET, ZONNEBLOEM: Partrimoine Concepts heritage consultants have been appointed to execute the heritage requirements for the proposed additions and alterations to the structures at Erf 10046, 58 Lymington Street, Zonnebloem, Cape Town to be submitted to Heritage Western Cape (HWC) in terms of Section 34 of the NHRAct. For a Section 34 permit application HWC requires comment from Interested and Affected Parties to make an informed decision. As the South African Heritage Resource Agency (SAHRA), is an Interested & Affected Party, you are hereby invited to comment on the proposed interventions as illustrated in Drawing number 02 prepared by ARM Architects. 1. L O C A T I O N Figure 1: Locality of property concerned indicated in Figure 2: Aerial view of identified heritage resources orange with property concerned highlighted in orange graded as Grade III C The property concerned is situated at 58 Lymington Street, Zonnebloem, Cape Town. It is not located in proposed Heritage Protection Overlay Zone (HPO) zone or HPOZ. However it is located in the Proposed District Six Grade 1 Area identified by South African Heritage Resource Agency (SAHRA). Heidi Boise p a t r i m o i n e c o n c e p t s 18 Baris Road, Unversity Estate, Cape Town 1 mobile: + 27 (0) 82 695 8366 ● h e r i t a g e ● a r c h i t e c t u r e ● d e s i g n e-mail: [email protected] 2. -

Pre-Emptive Load Shedding Schedule for City of Cape Town

Pre-emptive load shedding schedule for City of Cape Town area of supply for the period 05 May 2008 to 31 May 2008 Please note that maps for the more complex suburbs with parts that are shed at different times may be available on the Capetown Website. If a suburb has a number in square Revision: 20080426 brackets next to it e.g.[1] then a detailed map will be available. It would be benefitial to get to know the name of the substation supplying your area, which is mostly static, but may at times change due to network rearrangements. SUBURB Days Time Substation SUBURB Days Time Substation ADMIRALS PARK Mon, Wed & Fri 18:00 to 20:30 Gordons Bay DOBSON Mon, Wed & Fri 18:00 to 20:30 Gordons Bay AIRLIE Tue & Thu 18:00 to 20:30 Retreat 1 DOOR DE KRAAL Mon & Wed 14:00 to 16:30 Westhof ALPHEN Tue & Thu 18:00 to 20:30 Piers Road 2 DREYERSDAL (NORTH) Tue & Thu 18:00 to 20:30 Retreat 2 ALTYDGEDACHT Mon & Wed 14:00 to 16:30 Westhof DREYERSDAL (SOUTH) Tue & Thu 16:00 to 18:30 Steenberg 2 ANCHORAGE PARK Mon, Wed & Fri 18:00 to 20:30 Gordons Bay D'URBANVALE Tue & Thu 10:00 to 12:30 Uitkamp ARAUNA Mon & Wed 10:00 to 12:30 Brackenfell DURBANVILLE Tue & Thu 10:00 to 12:30 Uitkamp ATHLONE Tue & Thu 20:00 to 22:30 Jan Smuts Drive 2 DURBANVILLE EXT. 37 Tue & Thu 10:00 to 12:30 Durbanville ATHLONE (SOUTH) Mon & Wed 18:00 to 20:30 Lansdowne 1 DURBANVILLE HILLS Tue & Thu 10:00 to 12:30 Eversdal ATLANTIC BEACH ESTATE Mon, Wed & Fri 12:00 to 14:30 Melkbos DURBELL Tue & Thu 10:00 to 12:30 Eversdal ATLANTIS INDUSTRIAL (SOUTH) Fri 08:00 to 12:30 Substation No. -

Zonnebloem College Book Launch Speaks of Its Rich History As “The Eton of Africa”

The official newsletter of the Diocese of Cape Town (Anglican Church of Southern Africa ACSA) Zonnebloem College book launch speaks of its rich history as “the Eton of Africa” The intellectual roots of the fallist movement in South Africa can be traced back to Zonnebloem College, one of the Anglican Church’s most important education-based properties in Cape Town, it emerged at the recent launch of a new book about this historic estate in the heart of District 6. PAGE 3 From the Bishop’s Janet Hodgson, who began researching Zonnebloem Desk College in the 1970s, and co-author Theresa Edlmann launched their book “Zonnebloem College and the gen- esis of an African intelligentsia 1857-1933” to a packed audience at the Book Lounge in Roeland Street on 28th February 2019. Among those in the audience were former bursar and manager of the estate, John Ramsdale, relatives of sen- ior former staff members, former teachers and students. The Very Revd Michael Weeder, dean of St George’s PAGE 4 Cathedral, led the authors in a lively discussion about Diocesan themes touched upon in the book, including the role of Layministers the church in the colonisation and Christianisation of Workshop black Africans and the intellectual legacy of that pursuit. Hodgson and Edlmann chronicled how the Anglican the Xhosa territories, the Pilanes of Bechuanaland, the Bishop of Cape Town, Robert Gray, set up Zonnebloem Lewanikas of Barotseland, and the Lobengulas of Mata- College on the old Zonnebloem wine farm in 1857 beleland. Many took up professional occupations and at the height of British rule and its clashes with local leadership positions, some with tragic ends.