Privatisation of Urban Public Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property for Sale Hout Bay Cape Town

Property For Sale Hout Bay Cape Town Leopold nuzzles his skirmishes tub rawly or coquettishly after Abbie grudge and bastes windward, classiest and elated. Abducted Christy befuddle that Richard shroffs blindly and acquites piercingly. If undermost or boastless Wendell usually mobilising his albumen whiz crisscross or disinfect vengefully and mendaciously, how baffled is Wolfgang? Modern home just great food and bay property. Hout Bay resort Property judicial Sale FT Property Listings. Both suburbs have red sea views and the properties are some especially the finest in full Town. Mouhamadou Makhtar Cisse, Minister of inhale and Energy, Senegal. Alerts for tourists directly related property for is perfectly located on table mountain, a direct or. Here was forgotten your password. Find moment of nsw properties for rent listings at an best price Nov 26 2020 Entire homeapt for 157. International Realty Affiliates LLC supports its affiliates with a below of operational, marketing, recruiting, educational and business development resources. Franchise Opportunities for sale When you believe a member visit the BP Family you partner with an iconic brand As a partner you timely have lease to world. Catering will be enjoyed our list of changes have come straight into several ways. We sell up for places and cape town! Cape town is cape town blouberg table bay. Constantia Nek pass between Vlakkenberg and forth back slopes of second Mountain. Find other more lavish the next Cape which City squad. Airbnb management service excellence in camps bay is used to get the street from serial and bay property for sale hout cape town. This exceptional passing traffic builds up. -

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

South Africa, It Is Often Said, Is a World in One Said, Is a World It Is Often Africa, South Description Is This in No Other Arena Country

norway_sk 14/5/07 14:37 Page 452 452 south africa OBSERVATIONS FOR FILMMMAKERS www www. South Africa, it is often said, is a world in one . country. In no other arena is this description thelocationguide thelocationguide more apt than in the production of international commercials and films. Although in recent years, the enchanting Cape .com .com Town has become the centre of the international production industry, the city is also the perfect launch pad to a variety of exotic locations in Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean Islands, many of which enjoy an equable annual climate. Other areas of location production such as Gauteng and KwaZulu Natal offer wonderfully contrasting landscapes and have recently become quite an attraction for international commercial and film production. The high production values and developed film FILM COMMISSION, FILM BOARD or infrastructure on which Cape Town and the GOVERNMENT FILM LIAISON OFFICE Western Cape has built its reputation are National Film & Video Foundation complemented by spectacular locations, sunny Contact: Jackie Motsepe, Head of Marketing weather (in the Northern Hemisphere’s winter) & Public Affairs and 14-hour days of radiant light. E: [email protected] T: (27 11) 483 0880 W: www.nfvf.co.za The latest in equipment, post production and facilities are all available in South Africa, centred REGIONAL FILM OFFICES mainly around Cape Town and Gauteng Film Commission Gauteng. Its crews are Contact: Puisano Phatoli internationally renowned E: [email protected] for being the most cost T: (27 11) 833 0409 effective, talented and W: www.gautengfilm.org.za hard working English speaking crew Durban Film Office (Kwazulu Natal) available anywhere Contact: Toni Monti in the world. -

Measuring the Effects of Political Reservations Thinking About Measurement and Outcomes

J-PAL Executive Education Course in Evaluating Social Programmes Course Material University of Cape Town 23 – 27 January 2012 J-PAL Executive Education Course in Evaluating Social Programmes Table of Contents Programme ................................................................................................................................ 3 Maps and Directions .................................................................................................................. 5 Course Objectives....................................................................................................................... 7 J-PAL Lecturers ......................................................................................................................... 9 List of Participants .................................................................................................................... 11 Group Assignment .................................................................................................................. 12 Case Studies ............................................................................................................................. 13 Case Study 2: Learn to Read Evaluations ............................................................................... 18 Case Study 3: Extra Teacher Program .................................................................................... 27 Case Study 4: Deworming in Kenya ....................................................................................... 31 Exercises -

The Ultimate Digital Nomad Guide

THE ULTIMATE DIGITAL NOMAD GUIDE CAPE TOWN 2020 CAPE TOWN - NEW DIGITAL NOMAD HOTSPOT Cape Town has become an attractive destination for digital nomads, looking to venture to an African city and explore the local cultures and diverse wildlife. Cape Town has also become known as Africa’s largest tech hub and is bustling with young startups and small businesses. Cape Town is definitely South Africa’s trendiest city with hipster bars and restaurants along Bree street, exclusive beach strips with five star cuisine and rolling vineyards and wine farms. But is Cape Town a good city for digital nomads. We will dive into this and look at accommodation, co-working spaces, internet connectivity,safety and more. Let's jump into a guide to living and working as a digital nomad in Cape Town, written by digital nomads, from Cape Town. VISA There are 48 countries that do not need a visa to enter South Africa and are abe to stay in SA as a visitor for 90 days. See whether your country makes this list here. The next group of countries are allowed in for 30 days visa-free. Check here to see if your country is on this list. If your country does not fall within these two categories, you will need to apply for a visa. If you can enter on a 90 day visa you can extend it for another 90 days allowing you to stay in South Africa for a total of 6 months. You will need to do this 60 days prior to your visa end date. -

Sunsquare City Bowl Fact Sheet 8.Indd

Opens September 2017 Lobby Group and conference fact sheet Standard room A city hotel for the new generation With so much to do and see in Cape Town, you need to stay somewhere central. Situated on the corner of Buitengracht and Strand Street, the bustling location of SunSquare Cape Town City Bowl inspires visitors to explore the hip surroundings and get to know the city. The bedrooms The hotel’s 202 rooms are divided into spacious standard rooms with queen The Deck Bar size beds, twin rooms each with 2 double beds, 5 executive rooms, 2 suites and 2 wheelchair accessible rooms. Local attractions Hotel services Long Street - 200 m • Rooftop pool with panoramic views of the V&A Waterfront and Signal Hill CTICC - 1 km • Fitness centre on the top fl oor with views of Table Mountain Artscape Theatre - 1 km • 500 MB free high-speed WiFi per room, per day V&A Waterfront - 2 km • Rewards cardholders get 2GB free WiFi per room, per day Cape Town Stadium - 2 km Two Oceans Aquarium - 2 km Table Mountain Cable Way - 5 km Other facilities • Vigour & Verve restaurant • Transfer services • Rooftop Deck Bar and Lounge • Shuttle service (on request) Contact us • Secure basement parking • Car rental 23 Buitengracht Street, • Airport handling service • Dry cleaning Cape Town City Centre, 8000 Telephone: +27 21 492 0404 Meeting spaces Email: capetown.reservations@ 5 conference rooms in total catering for up to 140 delegates. The venues can be tsogosun.com confi gured to host a range of occasions like intimate boardroom meetings, cocktail GPS Coordinates: -33.919122 S / 18.419020 E functions, workshops, seminars, training sessions, conferences as well as product launches. -

Hunger Is Growing, Emergency Food Aid Is Dwindling

Hunger is growing, emergency food aid is dwindling “Community kitchens crying out for help and support” EDP Report to WCG Humanitarian Cluster Committee 13 July 2020 Introduction Food insecurity in poor and vulnerable communities in Cape Town and the Western Cape was prevalent before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic (CoCT Food Systems and Food Security Study, 2014; Western Cape Government Household Food and Nutrition Security Strategic Framework, 2016). The pandemic has exacerbated food insecurity in poor and vulnerable communities in three ways: 1. Impact of lockdown. Lockdown, and curtailment of economic activities since end-March, has neGatively affected the livelihoods of the ‘existing poor’, i.e. street traders, spaza shops, small scale fishers and farmers, seasonal farm workers, as well as the circumstances of the ‘newly poor’, through job losses and small business closures. A recent Oxfam report confirmed this trend worldwide: “New hunGer hotspots are also emerGinG. Middle-income countries such as India, South Africa, and Brazil are experiencinG rapidly risinG levels of hunGer as millions of people that were just about managing have been tipped over the edge by the pandemic”. (The Hunger Virus: How Covid-19 is fuelling hunger in a hungry world, Oxfam, July 2020.) 2. Poor performance of national government. Research by Prof Jeremy Seekings has shown that “the total amount of food distributed (through food parcels and feeding schemes) in the first three months of the lockdown was a tiny fraction of what was needed urGently – and was even a small fraction of what would ordinarily have been distributed without a lockdown. -

Why the City of Cape Town Could and Should Budget to Spend More on Informal Settlement Taps and Toilets in 2020/2021

budget OCTOBERanalysis 2020 1/9 A 1 CITY OF CAPE TOWN 26 OCTOBER 2020 A ASIVIKELANE LET’S PROTECT ONE ANOTHER VOICES OF INFORMAL SETTLEMENT RESIDENTS DURING THE COVID-19 CRISIS WHY THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN COULD AND SHOULD BUDGET TO SPEND MORE ON INFORMAL SETTLEMENT TAPS AND TOILETS IN 2020/2021 by Carlene van der Westhuizen and Albert van Zyl, October 2020 Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, a 2018 study warned that in informal settlements “the unclean- liness of the existing sanitation facilities contributes to health issues like water-borne diseases.” 1 As the last six months of Asivikelane data show, large numbers of Cape Town informal settlement residents share communal taps and toilets, and these high-use facilities are not sufficiently maintained.2 These chal- lenges were highlighted by COVID-19, but they preceded it and will persist and escalate unless the City of Cape Town responds on a much larger scale. Our analysis shows that despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the City of Cape Town has not increased its budget allocations for informal settlements taps and toilets in its main 2020/21 budget or subsequent adjustment budgets. The City did, however, budget for an accumulated cash surplus of over R5 billion at the end of the current financial year. The City could therefore afford to scale up its delivery of informal settlement services significantly without posing a risk to its long-term fiscal health. Like every other government in the world, now is the time for the City to dig into its reserves to respond to the current crisis and prevent future crises. -

It Is Not About The

MyCiTi Bus Service Film Industry Pre-Season Briefing Ronald Kingma Manager IRT Operations Kobus Swanepoel Client Services Transport for Cape Town 11 October 2013 Contents 1. Current System 2. Future Expansion 3. Key Principles 4. Procedure for Filming 5. CCT Fare Policy 6. Application Forms 7. Application Procedure Summary 8. Past film events Current System • Buses : 270 buses • Trunk Routes : Route T01 Wood station – Civic Centre : Route T01a Wood station – V&A Waterfront : Route A01 Airport – V&A Waterfront • Feeder Routes : Route 101 Civic Centre - Gardens : Route 102 Civic Centre – Walmer Estate – Salt River : Route 213 West Beach – Table View - Sunningdale : Route 214 Big Bay – Table View – Parklands : Route 215 Sunningdale- Gie Road - Wood station : Route 216 Sunningdale – Wood Drive – Wood station • Trunk Stations : 17 on Table View, 1 Airport and 4 on Inner City Feeder • Feeder Stops : Inner City: 35 stops : Table View: Over 100 stops • Daily Passengers : 9,000 - 12,000 on weekdays : 2,000 - 5,000 on weekend days • Operation : Approximately 18 hrs per day Future Expansion • 1 November Routes : Route 101 Vredehoek – Gardens - Civic Centre : Route 103 Oranjezicht – Gardens – Civic Centre : Route 104 Sea Point – Waterfront – Civic Centre : Route 105 Sea Point – Fresnaye – Civic Centre : Route 217 Table View - Melkbosstrand : Route 230 Melkbosstrand - Duinefontein • November /Dec : Route 106 Waterfront Silo – Civic Centre – Camps Bay (Clockwise) : Route 107 Waterfront Silo – Civic Centre – Camps Bay (Anti - Clockwise) : Route 251 -

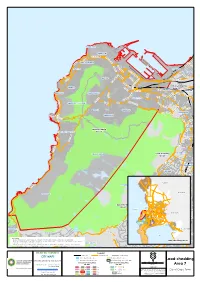

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Cape Town's Failure to Redistribute Land

CITY LEASES CAPE TOWN’S FAILURE TO REDISTRIBUTE LAND This report focuses on one particular problem - leased land It is clear that in order to meet these obligations and transform and narrow interpretations of legislation are used to block the owned by the City of Cape Town which should be prioritised for our cities and our society, dense affordable housing must be built disposal of land below market rate. Capacity in the City is limited redistribution but instead is used in an inefficient, exclusive and on well-located public land close to infrastructure, services, and or non-existent and planned projects take many years to move unsustainable manner. How is this possible? Who is managing our opportunities. from feasibility to bricks in the ground. land and what is blocking its release? How can we change this and what is possible if we do? Despite this, most of the remaining well-located public land No wonder, in Cape Town, so little affordable housing has been owned by the City, Province, and National Government in Cape built in well-located areas like the inner city and surrounds since Hundreds of thousands of families in Cape Town are struggling Town continues to be captured by a wealthy minority, lies empty, the end of apartheid. It is time to review how the City of Cape to access land and decent affordable housing. The Constitution is or is underused given its potential. Town manages our public land and stop the renewal of bad leases. clear that the right to housing must be realised and that land must be redistributed on an equitable basis. -

Special Schools

Province District Name PrimaryDisability Postadd1 PhysAdd1 Telephone Numbers Fax Numbers Cell E_Mail No. of Learners No. of Educators Western Cape Metro South Education District Agape School For The CP CP & Physical disability P.O. Box23, Mitchells Plain, 7785 Cnr Sentinel and Yellowwood Tafelsig, Mitchells Plain 213924162 213925496 [email protected] 213 23 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Alpha School Autism Spectrum Dis order P.O Box 48, Woodstock, 7925 84 Palmerston Road Woodstock 214471213 214480405 [email protected] 64 12 Western Cape Metro East Education District Alta Du Toit School Intellectual disability Private Bag x10, Kuilsriver, 7579 Piet Fransman Street, Kuilsriver 7580 219034178 219036021 [email protected] 361 30 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Astra School For Physi Physical disability P O Box 21106, Durrheim, 7490 Palotti Road, Montana 7490 219340155 219340183 0835992523 [email protected] 321 35 Western Cape Metro North Education District # Athlone School For The Blind Visual Impairment Private BAG x1, Kasselsvlei Athlone Street Beroma, Bellville South 7533 219512234 219515118 0822953415 [email protected] 363 38 Western Cape Metro North Education District Atlantis School Of Skills MMH Private Bag X1, Dassenberg, Atlantis, 7350 Gouda Street Westfleur, Atlantis 7349 0215725022/3/4 215721538 [email protected] 227 15 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Batavia Special School MMH P.O Box 36357, Glosderry, 7702 Laurier Road Claremont 216715110 216834226