A Visual Guide to the Us Fleet Submarines Part Four: Porpoise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler’S War Against Caribbean Oil

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler’s War Against Caribbean Oil Bercuson, David J.; Herwig, Holger H. University of Calgary Press Bercuson, D. J. & Herwig, H. H. "Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler’s War Against Caribbean Oil". Beyond Boundaries: Canadian Defence and Strategic Studies Series; 4. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49998 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com LONG NIGHT OF THE TANKERS: HITLER’S WAR AGAINST CARIBBEAN OIL David J. Bercuson and Holger H. Herwig ISBN 978-1-55238-760-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Introduction to Sonar, Navy Training Course. INSTITUTION Bureau of Naval Personnel, Washington, R

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 070 572 SE 014 119 TITLE Introduction to Sonar, Navy Training Course. INSTITUTION Bureau of Naval Personnel, Washington, R. C.-; Naval Personnel Program Support Activity, Washington, D. C. REPORT NO NAVPERS -10130 -B PUB DATE 68 NOTE 186p.; Revised 1968 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Acoustics; Instructional Materials; *Job Training; *Military Personnel; Military Science; Military Training; Physics; *Post Secondary Education; *Supplementary Textbooks ABSTRACT Fundamentals of sonar systems are presented in this book, prepared for both regular navy and naval reserve personnel who are seeking advancement in rating. An introductory description is first made of submarines and antisubmarine units. Determination of underwater targets is analyzed from the background of true and relative bearings, true and relative motion, and computation of target angles. Then, applications of both active and passive sonars are explained in connection with bathythesmographs, fathometers, tape recorders, fire control techniques, tfiternal and external communications systems, maintenance actions, test methods and equipment, and safety precautions. Basic principles of sound and temperature effects on wave propagation are also discussed. Illustrations for explanation use, information on training films and the sonar technician rating structure are also provided.. (CC) -^' U.S DEPARTMENT OFHEALTH. EDUCATION 14 WELFARE OFFICE OF EOUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HASBEEN REPRO OUCED EXACTLY ASRECEIVED FROM THE PERSON ORORGANIZATION ORIG INATING IT POINTS OFVIEW OR OPIN IONS STATED 00NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICEDF EDU CATION POSITION ORPOLICY 1-1:1444646- 1 a 7 ero AIM '440, a 40 ;13" : PREFACE. This book is written for themen of the U. S. Navy and Naval Reserve who are seeking advancement in theSonar Technician rating. -

U.S. Gato Class 26 Submarine Us Navy Measure 32/355-B

KIT 0384 85038410200 GENERAL HULL PAINT GUIDE U.S. GATO CLASS 26 SUBMARINE US NAVY MEASURE 32/355-B In the first few months immediately following the Japanese attack on surface and nine knots under water. Their primary armament consisted Pearl Harbor, it was the U. S. Navy’s submarine force that began unlimited of twenty-four 21-inch torpedoes which could be fired from six tubes in the warfare against Japan. While the surfaces forces regrouped, the submarines bow and four in the stern. Most GATO class submarines typically carried began attacking Japanese shipping across the Pacific. Throughout the war, one 3-inch, one 4-inch, or one 5-inch deck gun. To defend against aircraft American submarines sunk the warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy and while on the surface, one or two 40-mm guns were usually fitted, and cut the lifeline of merchant vessels that provided Japan with oil and other these were supplemented by 20mm cannon as well as .50 caliber and vital raw materials. They also performed other important missions like staging .30 caliber machine guns. Gato class subs were 311'9" long, displaced commando raids and rescuing downed pilots. The most successful of the 2,415 tons while submerged, and carried a crew of eighty-five men. U. S. fleet submarines during World War II were those of the GATO class. Your hightly detailed Revell 1/72nd scale kit can be used to build one of Designed to roam the large expanses of the Pacific Ocean, these submarines four different WWII GATO class submarines: USS COBIA, SS-245, USS were powered by two Diesel engines, generating 5,400 horse power for GROWLER, SS-215, USS SILVERSIDES, SS-236, and the USS FLASHER, operating on the surface, and batteries provided power while submerged. -

Submarines in the United States Navy - Wikipedia Page 1 of 13

Submarines in the United States Navy - Wikipedia Page 1 of 13 Submarines in the United States Navy There are three major types of submarines in the United States Navy: ballistic missile submarines, attack submarines, and cruise missile submarines. All submarines in the U.S. Navy are nuclear-powered. Ballistic subs have a single strategic mission of carrying nuclear submarine-launched ballistic missiles. Attack submarines have several tactical missions, including sinking ships and subs, launching cruise missiles, and gathering intelligence. The submarine has a long history in the United States, beginning with the Turtle, the world's first submersible with a documented record of use in combat.[1] Contents Early History (1775–1914) World War I and the inter-war years (1914–1941) World War II (1941–1945) Offensive against Japanese merchant shipping and Japanese war ships Lifeguard League Cold War (1945–1991) Towards the "Nuclear Navy" Strategic deterrence Post–Cold War (1991–present) Composition of the current force Fast attack submarines Ballistic and guided missile submarines Personnel Training Pressure training Escape training Traditions Insignia Submarines Insignia Other insignia Unofficial insignia Submarine verse of the Navy Hymn See also External links References https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Submarines_in_the_United_States_Navy 3/24/2018 Submarines in the United States Navy - Wikipedia Page 2 of 13 Early History (1775–1914) There were various submersible projects in the 1800s. Alligator was a US Navy submarine that was never commissioned. She was being towed to South Carolina to be used in taking Charleston, but she was lost due to bad weather 2 April 1863 off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. -

The Submarine Simulation

THE SUBMARINE SIMULATION INTRODUCTION Silent Service is a detailed simulation of World War II submarine missions in the Pacific. It places you into the role of submarine captain and presents you with the same information, problems and resources available to an actual sub captain. Included are numerous scenarios, options and play variations. Five detailed battle station screens, numerous commands, and realistic graphics and sound effects combine to provide a dramatic level of realism and playability. As is detailed later, US submarines played a crucial role in stemming the tide of Japanese imperialism and winning the war in the Pacific. The primary mission of the American Silent Service was to take on the Japanese Navy in their home waters and to neutralise the Japanese Merchant Marine. As submarine commander in this elite force, you will be evaluated based on the number and types of ship which you sink. The first group of scenarios recreate actual historical situations and require a variety of different tactics. They are useful for becoming acquainted with the mechanics of this simulation, practising specific situations, or for quick games. The real test of a submariner's skill however, are are the Patrol scenarios. Here you will encounter an almost infinite variety of situations as you seek out and attack enemy convoys. With a limited number of torpedoes and fuel, your goal is to sink a maximum tonnage of enemy shipping and bring your sub successfully back to base. As an accurate simulation of a real life-situation, there are numerous details, subtleties and features included in the simulation. -

English Comes from the French: Guerre De Course

The Maritime Transport War - Emphasizing a strategy to interrupt the enemy sea lines of communication1 (SLOCs) - ARAKAWA Kenichi Preface Why did the Imperial Japanese Navy not aggressively develop a strategy to interrupt the enemy sea line of communication (SLOC) during the Second World War? Japan’s SLOC connecting her southern and Asian continental fronts to the mainland were destroyed mainly by the U.S. submarine warfare. Consequently, Japanese forces suffered from shortages of provisions as well as natural resources necessary for her military power. Furthermore, neither weapons nor provisions could be delivered to the fronts due to the U.S. operations to disrupt the Japanese SLOCs between the battlegrounds and the Japanese home island. Thus soldiers on the front were threatened with starvation even before the battle. In contrast, the U.S. and British military forces supported long logistical supply lines to their Asian and Pacific battlegrounds. However, there are no records indicating that the Imperial Japanese Navy attempted to interrupt these vital sea lines. Surely Japanese officers were aware of the German use of submarines in World WarⅠ. Why did the Imperial Japanese Navy not adopt a guerre de course strategy, that is a strategy targeting the enemy merchant marine and logistical lines? The most comprehensive explanation indicates that the Imperial Japanese Navy had no doctrine providing for this kind of warfare. The core of its naval strategy was the doctrine of “decisive battles at any cost.” Under the Japanese naval doctrine submarines were meant to contribute to fleet engagements not to have an independent combat role or to target anything but the enemy fleet. -

2. Location Street a Number Not for Pubhcaoon City, Town Baltimore Vicinity of Ststs Maryland Coot 24 County Independent City Cods 510 3

B-4112 War 1n the Pacific Ship Study Federal Agency Nomination United States Department of the Interior National Park Servica cor NM MM amy National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form dato««t«««d See instructions in How to CompMe National Raglatar Forma Type all entries—complsts applicable sections 1. Name m«toMc USS Torsk (SS-423) and or common 2. Location street a number not for pubHcaOon city, town Baltimore vicinity of ststs Maryland coot 24 county Independent City cods 510 3. Classification __ Category Ownership Status Present Use district ±> public _X occupied agriculture _X_ museum bulldlng(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure both work In progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious JL_ object in process X_ yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted Industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Baltimore Maritime Museum street * number Pier IV Pratt Street city,town Baltimore —vicinltyof state Marvlanrf 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Department of the Navy street * number Naval Sea Systems Command, city, town Washington state pc 20362 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title None has this property been determined eligible? yes no date federal state county local depository for survey records ctty, town . state B-4112 Warships Associated with World War II In the Pacific National Historic Landmark Theme Study" This theme study has been prepared for the Congress and the National Park System Advisory.Board in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Public Law 95-348, August 18, 1978. The purpose of the theme study is to evaluate sur- ~, viving World War II warships that saw action in the Pacific against Japan and '-• to provide a basis for recommending certain of them for designation as National Historic Landmarks. -

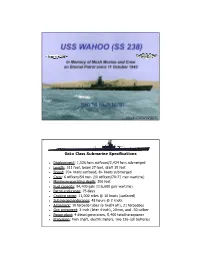

Gato Class Submarine Specifications

1 Prepared by a former Mare Island yardbird, in memory of those who have gone before him 2 Gat o Class Submarine Specificat ions z Displace ment: 1,526 tons surfaced/2,424 tons submerged z Length: 311 feet, beam 27 feet, draft 15 feet z Speed: 20+ knots surfaced, 8+ knots submerged z Crew: 6 officers/54 men (10 officers/70-71 men wartime) z Maximum operating depth: 300 feet z Fuel capacity: 94,400 gals (116,000 gals wartime) z Patrol endurance: 75 days z Cruising range: 11,000 miles @ 10 knots (surfaced) z Submerged endurance: 48 hours @ 2 knots z A rma me nt : 10 torpedo tubes (6 fwd/4 aft), 21 torpedoes z Gun armament: 3-inch (later 4-inch), 20mm, and .50 caliber z Power plant: 4 diesel generators, 5,400 total horsepower z Propulsion: twin shaft, electric motors, two 126-cell batteries 3 Gato Class Internal Arrangement 4 Combat History of USS Wahoo z Seven war patrols z Credited with sinking 27 ships totaling over 125,000 tons z Earned 6 battle stars and awarded a Presidential Unit Citation z Commanded by CDR Dudley W. “Mush” Morton on last five patrols z One of 52 U.S. submar ines lost in WWII z Wahoo and other U.S. submarines completed 1,560 war patrols and sank over 5.6 million tons of Japanese shipping Wahoo patch & battle flag 5 Keel Laying - 28 June 1941 6 Wahoo Pressure Hull Sect ions - 1941 7 Under Construction on Building Way - January 1942 8 Launching Day - 14 February 1942 9 Launching Sponsor - Mrs. -

Shokaku Class, Zuikaku, Soryu, Hiryu

ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF KOJINSHA No.6 ‘WARSHIPS OF THE IMPERIAL JAPANESE NAVY’ SHOKAKU CLASS SORYU HIRYU UNRYU CLASS TAIHO Translators: - Sander Kingsepp Hiroyuki Yamanouchi Yutaka Iwasaki Katsuhiro Uchida Quinn Bracken Translation produced by Allan Parry CONTACT: - [email protected] Special thanks to my good friend Sander Kingsepp for his commitment, support and invaluable translation and editing skills. Thanks also to Jon Parshall for his work on the drafting of this translation. CONTENTS Pages 2 – 68. Translation of Kojinsha publication. Page 69. APPENDIX 1. IJN TAIHO: Tabular Record of Movement" reprinted by permission of the Author, Colonel Robert D. Hackett, USAF (Ret). Copyright 1997-2001. Page 73. APPENDIX 2. IJN aircraft mentioned in the text. By Sander Kingsepp. Page 2. SHOKAKU CLASS The origin of the ships names. Sho-kaku translates as 'Flying Crane'. During the Pacific War, this powerful aircraft carrier and her name became famous throughout the conflict. However, SHOKAKU was actually the third ship given this name which literally means "the crane which floats in the sky" - an appropriate name for an aircraft perhaps, but hardly for the carrier herself! Zui-kaku. In Japan, the crane ('kaku') has been regarded as a lucky bird since ancient times. 'Zui' actually means 'very lucky' or 'auspicious'. ZUIKAKU participated in all major battles except for Midway, being the most active of all IJN carriers. Page 3. 23 August 1941. A near beam photo of SHOKAKU taken at Yokosuka, two weeks after her completion on 8 August. This is one of the few pictures showing her entire length from this side, which was almost 260m. -

Ship Hull Classification Codes

Ship Hull Classification Codes Warships USS Constitution, Maine, and Texas MSO Minesweeper, Ocean AKA Attack Cargo Ship MSS Minesweeper, Special (Device) APA Attack Transport PC Patrol Coastal APD High Speed Transport PCE Patrol Escort BB Battleship PCG Patrol Chaser Missile CA Gun Cruiser PCH Patrol Craft (Hydrofoil) CC Command Ship PF Patrol Frigate CG Guided Missile Cruiser PG Patrol Combatant CGN Guided Missile Cruiser (Nuclear Propulsion) PGG Patrol Gunboat (Missile) CL Light Cruiser PGH Patrol Gunboat (Hydrofoil) CLG Guided Missile Light Cruiser PHM Patrol Combatant Missile (Hydrofoil) CV Multipurpose Aircraft Carrier PTF Fast Patrol Craft CVA Attack Aircraft Carrier SS Submarine CVE Escort Aircraft Carrier SSAG Auxiliary Submarine CVHE Escort Helicopter Aircraft Carrier SSBN Ballistic Missile Submarine (Nuclear Powered) CVL Light Carrier SSG Guided Missile Submarine CVN Multipurpose Aircraft Carrier (Nuclear Propulsion) SSN Submarine (Nuclear Powered) CVS ASW Support Aircraft Carrier DD Destroyer DDG Guided Missile Destroyer DE Escort Ship DER Radar Picket Escort Ship DL Frigate EDDG Self Defense Test Ship FF Frigate FFG Guided Missile Frigate FFR Radar Picket Frigate FFT Frigate (Reserve Training) IX Unclassified Miscellaneous LCC Amphibious Command Ship LFR Inshore Fire Support Ship LHA Amphibious Assault Ship (General Purpose) LHD Amphibious Assault Ship (Multi-purpose) LKA Amphibious Cargo Ship LPA Amphibious Transport LPD Amphibious Transport Dock LPH Amphibious Assault Ship (Helicopter) LPR Amphibious Transport, Small LPSS Amphibious Transport Submarine LSD Dock Landing Ship LSM Medium Landing Ship LST Tank Landing Ship MCM Mine Countermeasure Ship MCS Mine Countermeasure Support Ship MHC Mine Hunter, Coastal MMD Mine Layer, Fast MSC Minesweeper, Coastal (Nonmagnetic) MSCO Minesweeper, Coastal (Old) MSF Minesweeper, Fleet Steel Hulled 10/17/03 Copyright (C) 2003. -

The Archeology of the Atomic Bomb

THE ARCHEOLOGY OF THE ATOMIC BOMB: A SUBMERGED CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT OF THE SUNKEN FLEET OF OPERATION CROSSROADS AT BIKINI AND KWAJALEIN ATOLL LAGOONS REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS Prepared for: The Kili/Bikini/Ejit Local Government Council By: James P. Delgado Daniel J. Lenihan (Principal Investigator) Larry E. Murphy Illustrations by: Larry V. Nordby Jerry L. Livingston Submerged Cultural Resources Unit National Maritime Initiative United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers Number 37 Santa Fe, New Mexico 1991 TABLE OF CONTENTS ... LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ......................................... 111 FOREWORD ................................................... vii Secretary of the Interior. Manuel Lujan. Jr . ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................... ix CHAPTER ONE: Introduction ........................................ 1 Daniel J. Lenihan Project Mandate and Background .................................. 1 Methodology ............................................... 4 Activities ................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO: Operation Crossroads .................................. 11 James P. Delgado The Concept of a Naval Test Evolves ............................... 14 Preparing for the Tests ........................................ 18 The AbleTest .............................................. 23 The Baker Test ............................................. 27 Decontamination Efforts ....................................... -

Gato Class Boats Finished the War with a Mod 3A Fairwater

A VISUAL GUIDE TO THE U.S. FLEET SUBMARINES PART ONE: GATO CLASS (WITH A TAMBOR/GAR CLASS POSTSCRIPT) 1941-1945 (3rd Edition, 2019) BY DAVID L. JOHNSTON © 2019 The Gato class submarines of the United States Navy in World War II proved to be the leading weapon in the strategic war against the Japanese merchant marine and were also a solid leg of the triad that included their surface and air brethren in the USN’s tactical efforts to destroy the Imperial Japanese Navy. Because of this they have achieved iconic status in the minds of historians. Ironically though, the advancing years since the war, the changing generations, and fading memories of the men that sailed them have led to a situation where photographs, an essential part of understanding history, have gone misidentified which in some cases have led historians to make egregious errors in their texts. A cursory review of photographs of the U.S. fleet submarines of World War II often leaves you with the impression that the boats were nearly identical in appearance. Indeed, the fleet boats from the Porpoise class all the way to the late war Tench class were all similar enough in appearance that it is easy to see how this impression is justified. However, a more detailed examination of the boats will reveal a bewildering array of differences, some of them quite distinct, that allows the separation of the boats into their respective classes. Ironically, the rapidly changing configuration of the boats’ appearances often makes it difficult to get down to a specific boat identification.