9781483437163

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

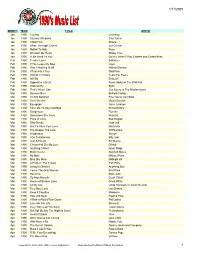

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

Como Fabricar Um Gangsta: Masculinidades Negras Nos Videoclipes Dos Rappers Jay-Z E 50 Cent

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE HUMANIDADES, ARTES E CIÊNCIAS PROFESSOR MILTON SANTOS PROGRAMA MULTIDISCIPLINAR DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CULTURA E SOCIEDADE COMO FABRICAR UM GANGSTA: MASCULINIDADES NEGRAS NOS VIDEOCLIPES DOS RAPPERS JAY-Z E 50 CENT por DANIEL DOS SANTOS Orientador(a): Prof. Dr. Leandro Colling SALVADOR 2017 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE HUMANIDADES, ARTES E CIÊNCIAS PROFESSOR MILTON SANTOS PROGRAMA MULTIDISCIPLINAR DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CULTURA E SOCIEDADE COMO FABRICAR UM GANGSTA: MASCULINIDADES NEGRAS NOS VIDEOCLIPES DOS RAPPERS JAY-Z E 50 CENT por DANIEL DOS SANTOS Orientador: Prof. Dr. Leandro Colling Dissertação apresentada ao Programa Multidisciplinar de Pós-Graduação em Cultura e Sociedade do Instituto de Humanidades, Artes e Ciências como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do grau de Mestre. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Leandro Colling SALVADOR 2017 Ficha catalográfica elaborada pelo Sistema Universitário de Bibliotecas (SIBI/UFBA), com os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a). Dos Santos, Daniel Como Fabricar um Gangsta: Masculinidades Negras nos Videoclipes dos Rappers Jay-Z e 50 Cent / Daniel Dos Santos. -- Salvador - Bahia, 2017. 175 f. : il Orientador: Leandro Colling. Dissertação (Mestrado - Programa Multidisciplinar de Pós-Graduação em Cultura e Sociedade) -- Universidade Federal da Bahia, Instituto de Humanidades, Artes e Ciências Professor Milton Santos, 2017. 1. Raça. 2. Gênero. 3. Masculinidades Negras. 4. Gangsta Rap. 5. Representação. I. Colling, Leandro. II. Título. Em memória de Maria Izabel Francisca Dos Santos, minha mãe. Todos os meus textos e títulos são seus. Para meu pai Franklin Pereira Dos Santos e todos os homens negros que falam a língua do silêncio. Para Marcos Santos, o amigo que o Atlântico Negro me deu. -

Never Change 2.1

Never Change 2.1: A Look at Jay-Z’s Lyrical Evolution kashema h. www.kashema.com Never Change 2.1: A look Jay-Z’s Lyrical Evolution By kashema h. “Intro” Jay-Z’s classic album Reasonable Doubt (1996) turned 20 years old this summer but it has been two years since he has released another album. He released “Spiritual” after the extrajudicial killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. Jay is featured on the remix of “All the Way Up” and teamed up with DJ Khaled and Future to create “I Got the Keys.” Back in April, Mr. Carter made a cameo on his wife’s Beyoncé’s visual album, Lemonade as a family man. The last time we saw the lyricist in full rap mode (e.g. album, singles and tour) was for Magna Carta Holy Grail in 2013. The promotional On The Run trailer for the married couple’s tour stars Jay-Z and Beyoncé as bank robbers à la Bonnie and Clyde, and features all kinds of guns, ski masks, shady figures, cop chases and a line-up. In 2014, I started to think about Jay’s past criminal life as a drug dealer, and his references to it on his records. I let the thing between my eyes analyze Jay’s skills, then put it down—type Braille...you feel me? Last month, the rapper narrated the New York Times Op-Ed: “The War on Drugs Is an Epic Fail.” I went back to my study of Jay-Z and his lyrics with a more critical eye. -

Columbus-OH-Winners.Pdf

Top Junior Petite Intermediate Soloist 1st Place 537 Somewhere Over the RainbowLoren Norman Dance ELITE Top Junior Petite Competitive Soloist 1st Place 111 Kindergarten Lovesong Naomi Smith Passe Dance Center Top Junior Competitive Soloist 1st Place 106 Your Hands Alexis Lombardi Passe Dance Center Top Junior Elite Soloist 1st Place 402 Follow Your Light Reese Callaway Cole Academy Top Junior Pre-Teen Intermediate Soloist 1st Place 546 Pretty Young Thing Eva Williford Dance ELITE Top 10 Junior Pre-Teen Competitive Soloists 1st Place 184 Birdsong Alexa Spohn Marjorie Jones Schools 2nd Place 185 Daughter Meghan Robertson Marjorie Jones Schools 3rd Place 210 Music Box Katie Sabatino Marjorie Jones Schools 4th Place 117 Runway Walk Leiana Rice Passe Dance Center 5th Place 180 Miss Otis Regrets Cara Lalli Marjorie Jones Schools 6th Place 105 Ain't She Sweet Kendall Alton Passe Dance Center 7th Place 570 Firehouse Ava Harrington Independent 8th Place 201 Fire Under Feet Sarah Shacter Marjorie Jones Schools 9th Place 510 Hi De Ho Man Enrico Dillon The Dance Space 10th Place 342 Before You Go Briana Ritchie YMCA Creative Arts Center Top 3 Junior Pre-Teen Elite Soloists 1st Place 300 Le Jazz Hot Delaney Constancio Powell Dance Academy 2nd Place 297 Dancin Fool Grace Bozic Powell Dance Academy 3rd Place 316 Big Noise Mackenzie Troutman Powell Dance Academy Top 5 Teen Competitive Soloists 1st Place 545 Sol Zion Robinson Dance ELITE 2nd Place 113 Try Adriana Tonello Passe Dance Center 3rd Place 539 In Christ Alone Rebekkah Day Dance ELITE 4th Place -

He Is Not Here; He Has Risen!

333 April, 2021 Easter Edition "Let Us Give Thanks To The God And Father Of Our Lord Jesus Christ! Because Of His Great Mercy He Gave Us New Life By Raising Jesus Christ From Death. This Fills Us With A Living Hope." (1 Peter 1:3 GNT) IT WAS NOW ABOUT NOON, and darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon, for the sun stopped shining. And the curtain of the temple was torn in two. Jesus called out with a loud voice, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit.” When he had said this, he breathed his last… Now there was a man named Joseph…a good and upright man…from the Judean town of Arimathea… Going to Pilate, he asked for Jesus’ body. Then he took it down, wrapped it in linen cloth and placed it in a tomb cut in the rock, one in which no one had yet been laid… ON THE FIRST DAY OF THE WEEK, very early in the morning, the women took the spices they had prepared and went to the tomb. They found the stone tolled away from the tomb, but when they entered, they did not find the body of the Lord Jesus. While they were wondering about this, suddenly two men in clothes that gleaned like lighting stood beside them. In their fright the women bowed down with their faces to the ground, but the men said to them, “Why do you look for the living among the dead?” He is not here; He has risen!. -

234 MOTION for Permanent Injunction.. Document Filed by Capitol

Arista Records LLC et al v. Lime Wire LLC et al Doc. 237 Att. 12 EXHIBIT 12 Dockets.Justia.com CRAVATH, SWAINE & MOORE LLP WORLDWIDE PLAZA ROBERT O. JOFFE JAMES C. VARDELL, ID WILLIAM J. WHELAN, ffl DAVIDS. FINKELSTEIN ALLEN FIN KELSON ROBERT H. BARON 825 EIGHTH AVENUE SCOTT A. BARSHAY DAVID GREENWALD RONALD S. ROLFE KEVIN J. GREHAN PHILIP J. BOECKMAN RACHEL G. SKAIST1S PAULC. SAUNOERS STEPHEN S. MADSEN NEW YORK, NY IOOI9-7475 ROGER G. BROOKS PAUL H. ZUMBRO DOUGLAS D. BROADWATER C. ALLEN PARKER WILLIAM V. FOGG JOEL F. HEROLD ALAN C. STEPHENSON MARC S. ROSENBERG TELEPHONE: (212)474-1000 FAIZA J. SAEED ERIC W. HILFERS MAX R. SHULMAN SUSAN WEBSTER FACSIMILE: (212)474-3700 RICHARD J. STARK GEORGE F. SCHOEN STUART W. GOLD TIMOTHY G. MASSAD THOMAS E. DUNN ERIK R. TAVZEL JOHN E. BEERBOWER DAVID MERCADO JULIE SPELLMAN SWEET CRAIG F. ARCELLA TEENA-ANN V, SANKOORIKAL EVAN R. CHESLER ROWAN D. WILSON CITYPOINT RONALD CAM I MICHAEL L. SCHLER PETER T. BARBUR ONE ROPEMAKER STREET MARK I. GREENE ANDREW R. THOMPSON RICHARD LEVIN SANDRA C. GOLDSTEIN LONDON EC2Y 9HR SARKIS JEBEJtAN DAMIEN R. ZOUBEK KRIS F. HEINZELMAN PAUL MICHALSKI JAMES C, WOOLERY LAUREN ANGELILLI TELEPHONE: 44-20-7453-1000 TATIANA LAPUSHCHIK B. ROBBINS Kl ESS LING THOMAS G. RAFFERTY FACSIMILE: 44-20-7860-1 IBO DAVID R. MARRIOTT ROGER D. TURNER MICHAELS. GOLDMAN MICHAEL A. PASKIN ERIC L. SCHIELE PHILIP A. GELSTON RICHARD HALL ANDREW J. PITTS RORYO. MILLSON ELIZABETH L. GRAYER WRITER'S DIRECT DIAL NUMBER MICHAEL T. REYNOLDS FRANCIS P. BARRON JULIE A. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Luke I Wanna Rock 4:23 Luke - Greatest Hits 8 1996 Rap 128 Disk Local 2 Angie Stone No More Rain (In this Cloud) 4:42 Black Diamond 1999 Soul 3 128 Disk Local 3 Keith Sweat Merry Go Round 5:17 I'll Give All My Love to You 4 1990 RnB 128 Disk Local 4 D'Angelo Brown Sugar (Live) 10:42 Brown Sugar 1 1995 Soul 128 Disk Grand Verbalizer, What Time Is Local 5 X Clan 4:45 To the East Blackwards 2 1990 Rap 128 It? Disk Local 6 Gerald Levert Answering Service 5:25 Groove on 5 1994 RnB 128 Disk Eddie Local 7 Intimate Friends 5:54 Vintage 78 13 1998 Soul 4 128 Kendricks Disk Houston Local 8 Talk of the Town 6:58 Jazz for a Rainy Afternoon 6 1998 Jazz 3 128 Person Disk Local 9 Ice Cube X-Bitches 4:58 War & Peace, Vol.1 15 1998 Rap 128 Disk Just Because God Said It (Part Local 10 LaShun Pace 9:37 Just Because God Said It 2 1998 Gospel 128 I) Disk Local 11 Mary J Blige Love No Limit (Remix) 3:43 What's The 411- Remix 9 1992 RnB 3 128 Disk Canton Living the Dream: Live in Local 12 I M 5:23 1997 Gospel 128 Spirituals Wash Disk Whitehead Local 13 Just A Touch Of Love 5:12 Serious 7 1994 Soul 3 128 Bros Disk Local 14 Mary J Blige Reminisce 5:24 What's the 411 2 1992 RnB 128 Disk Local 15 Tony Toni Tone I Couldn't Keep It To Myself 5:10 Sons of Soul 8 1993 Soul 128 Disk Local 16 Xscape Can't Hang 3:45 Off the Hook 4 1995 RnB 3 128 Disk C&C Music Things That Make You Go Local 17 5:21 Unknown 3 1990 Rap 128 Factory Hmmm Disk Local 18 Total Sittin' At Home (Remix) -

Download File

Get Crunk! The Performative Resistance of Atlanta Hip-Hop Party Music Kevin C. Holt Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 ©2018 Kevin C. Holt All rights reserved ABSTRACT Get Crunk! The Performative Resistance of Atlanta Hip-Hop Party Music Kevin C. Holt This dissertation offers an aesthetic and historical overview of crunk, a hip- hop subgenre that took form in Atlanta, Georgia during the late 1990s. Get Crunk! is an ethnography that draws heavily on methodologies from African-American studies, musicological analysis, and performance studies in order to discuss crunk as a performed response to the policing of black youth in public space in the 1990s. Crunk is a subgenre of hip-hop that emanated from party circuits in the American southeast during the 1990s, characterized by the prevalence of repeating chanted phrases, harmonically sparse beats, and moderate tempi. The music is often accompanied by images that convey psychic pain, i.e. contortions of the body and face, and a moshing dance style in which participants thrash against one another in spontaneously formed epicenters while chanting along with the music. Crunk’s ascension to prominence coincided with a moment in Atlanta’s history during which inhabitants worked diligently to redefine Atlanta for various political purposes. Some hoped to recast the city as a cosmopolitan tourist destination for the approaching new millennium, while others sought to recreate the city as a beacon of Southern gentility, an articulation of the city’s mythologized pre-Civil War existence; both of these positions impacted Atlanta’s growing hip-hop community, which had the twins goals of drawing in black youth tourism and creating and marketing an easily identifiable Southern style of hip-hop for mainstream consumption; the result was crunk. -

Winners Hot New Releases

sue 543 $6.00 May 19, 1997 Volume 11 HANSON WINNERS EARPICKS BREAKOUTS ILDCARD HANSON Mercury EN GUE EW/EEG COUNTING CROWS DGC SHERYL CROW A&M THIRD EYE BLIND Elek/EEG TIW SPROCKET Col/CRG BEE GEES Poly/A&M See P. e 14 For Details SHERYL CROW A&M INDIGO GIRLS Epic JON BON JOVI Mercury MEREDITH BROOKS Capitol JON BON JOVI Mercury BOB CARLISLE Jive COUNTING CROWS DGC STEADY MOBB'N Priority SISTER HAZEL Universal M.M. BOSSTONES Mercury HOT NEW RELEASES AALIYAH ALISHA'S ATTIC BABYFACE COLLECTIVE SOUL EN VOGUE 4 Page Letter I Am, I Feel How Come, How Long Listen Whatever Bel/MI/MI G 98021 Mercury N/A Epic N/A AtI/Atl G 84006 EW/EEG N/A JAMIROQUAI JONNY LANG PAUL McCARTNEY MASTA P Virtual Insanity Lie To Me The World Tonight If I Could Change WORK N/A A&M N/A Capitol N/A NI/Priority 53273 REAL Mc SHADES STEVE WINWOOD I Wanna Come (With You) Serenade Spy In The House Of Love Arista N/A Motown 3746-32062-2 Virgin N/A 117-- World Party It Is Time THE ENCLAVE 936 Broadway new york.n.y 10010, www.the-enclave.com May 19, 1997 Volume 11 Issue 543 $6.00 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher LENNY BEER VIBE-RATERS 4 Winning Ticket Editor In Chief Hanson are in the middle of somewhere and Meredith Brooks TONI PROFERA moves to the edge while the debuting Sammy Hagar and Executive Editor Supergrass grow. DAVID ADELSON Vice President/Managing Editor KAREN GLAUBER MOST POWERFUL SONGS 6 Senior Vice President Spice Girls just want to have fun at #1 over runner-up Mary J. -

The Coolest Music Book Ever Made Aka the MC 500 Vol. 1 Marcus Chapman Presents… the Coolest Music Book Ever Made Aka the MC 500 Vol

The Coolest Music Book Ever Made aka The MC 500 Vol. 1 Marcus Chapman presents… The Coolest Music Book Ever Made aka The MC 500 Vol. 1 k Celebrating 40 Years of Sounds, Life, and Culture Through an All-Star Team of Songs Marcus Chapman For everyone who knows the joy of spending time shopping in a record store, and for the kids of the present and future who will never have that experience… Copyright © 2015 Marcus Chapman All rights reserved. ISBN: 1511780126 ISBN 13: 9781511780124 Contents Intro: What is The MC 500 and What Makes This Book So Cool? BONUS SONG: #501 Ooh . Roy Ayers 500 to 401 500 You Don’t Know How It Feels . Tom Pett y 499 Diggin’ On You. TLC 498 Here I Go Again . Whitesnake 497 Blame It . Jamie Foxx featuring T-Pain 496 Just Shopping (Not Buying Anything) . The Dramatics 495 Girls Dem Sugar . Beenie Man featuring Mya 494 My Heart Belongs To U . Jodeci 493 What’s My Name? . Rihanna featuring Drake 492 Feel the Need . Chocolate Milk 491 Midnight Flight . Jake Jacobson 490 The Big Payback . EPMD 489 Still Talkin’ . Eazy-E 488 Too Hot Ta Trot . Commodores 487 Who Dat . JT Money featuring Solé 486 Dark Vader . Instant Funk 485 Flow On (Move Me No Mountain). Above the Law 484 Fantasy . Earth, Wind & Fire 483 Payback Is a Dog . The Stylistics 452 Life Can Be Happy . Slave 482 Double Vision . Foreigner 451 I’ll Take Your Man . Salt ‘N Pepa 481 Soliloquy of Chaos . Gang Starr 480 Spirit of the Boogie . -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 10-27-1999 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (1999). The George-Anne. 2949. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/2949 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Established 1927 The Official Student Newspaper of Georgia Southern University Lebkihg for some Halloween treats? Halloween is the time for treats and The George-Anne has some great recipes for that Halloween party you've RfcCEl ¥ EU Page 10 OCT 2 71399 HENDERSON LIBRARY Wednesday, October 27, 1999 GSU initiates new e-mail system By Shawntineal Hughes Assistant News Editor GSU has a new method of accessing e-mail accounts for faculty, staff, and students through the world wide web. This new program allows e-mail users to compose messages, read mes- sages and send messages and attach- ments. It does not allow them to have an address book or use different mail- boxes, which pine has. 'This is our first venture into a new area," John Gleissner, assistant direc- tor for technical support, said. "It seems like a good success with the limited features. We are trying to expand to the features of pine and hopefully that will come in the near BE AFRAID, BE VERY AFRAID: future." David Whiddon Recreation majors have been This program was tested over the E-MAIL CHANGES: GSU is revamping its e-mail system. -

The King of Love Willie Hobbs

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 The King of Love Willie Hobbs Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE KING OF LOVE By WILLIE HOBBS, III A Dissertation submitted to the English Department in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2004 Copyright © 2004 Willie Hobbs, III All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Willie Hobbs defended on May 6, 2004. Virgil Suarez Professor Directing Dissertation Maricarmen Martinez Outside Committee Member Elizabeth Stuckey-French Committee Member Darryl Dickson-Carr Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I’d like to thank God first and foremost for good health, good company and the sweet madness of hearing the muse… I’d like to thank my wife Dr. Tameka Bradley Hobbs and son Ashanti for support along this nerve-racking journey. I’d like to thank Ma and Dad and the rest of my family who have supported my unconventional dream… Much appreciation to the FEF McKnight Fellowship for making my matriculation possible. Equally in that respect, much thanks goes to professor Darryl Dickson-Carr for helping the scholar in me better define the artist in me. Much love to Virgil Suarez, Elizabeth Stuckey-French, Sheila Ortiz-Taylor (I’m getting mushy writing all this), Janet Burroway, the unstoppable Robert Olen Butler, the grouchy Bob Shacochis… Writing rules! Much thanks to Drs.