How Animacy and Verbal Information Influence V2 Sentence Processing: Evidence from Eye Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verbs Show an Action (Eg to Run)

VERBS Verbs show an action (e.g. to run). The tricky part is that sometimes the action can't be seen on the outside (like run) – it is done on the inside (e.g. to decide). Sometimes the action even has to do with just existing, in other words to be (e.g. is, was, are, were, am). Tenses The three basic tenses are past, present and future. Past – has already happened Present – is happening Future – will happen To change a word to the past tense, add "-ed" (e.g. walk → walked). ***Watch out for the words that don't follow this (or any) rule (e.g. swim → swam) *** To change a word to the future tense, add "will" before the word (e.g. walk → will walk BUT not will walks) Exercise 1 For each word, write down the correct tense in the appropriate space in the table below. Past Present Future dance will plant looked runs shone will lose put dig Spelling note: when "-ed" is added to a word ending in "y", the "y" becomes an "i" e.g. try → tried These are the basic tenses. You can break present tense up into simple present (e.g. walk), present perfect (e.g. has walked) and present continuous (e.g. is walking). Both past and future tenses can also be broken up into simple, perfect and continuous. You do not need to know these categories, but be aware that each tense can be found in different forms. Is it a verb? Can it be acted out? no yes Can it change It's a verb! tense? no yes It's NOT a It's a verb! verb! Exercise 2 In groups, decide which of the words your teacher gives you are verbs using the above diagram. -

Modals and Auxiliaries 12

Verbs: Modals and Auxiliaries 12 An auxiliary is a helping verb. It is used with a main verb to form a verb phrase. For example, • She was calling her friend. Here the word calling is the main verb and the word was is an auxiliary verb. The words be , have , do , can , could , may , might , shall , should , must , will , would , used , need , dare , ought are called auxiliaries . The verbs be, have and do are often referred to as primary auxiliaries. They have a grammatical function in a sentence. The rest in the above list are called modal auxiliaries, which are also known as modals. They express attitude like permission, possibility, etc. Note the forms of the primary auxiliaries. Auxiliary verbs Present tense Past tense be am, is, are was, were do do, does did have has, have had The table below illustrates the application of these primary verbs. Primary auxiliary Function Example used in the formation of She is sewing a dress. continuous tenses I am leaving tomorrow. be in sentences where the The missing child was action is more important found. than the subject 67 EBC-6_Ch19.indd 67 8/12/10 11:47:38 PM when followed by an We are to leave next infinitive, it is used to week. indicate a plan or an arrangement denotes command You are to see the Principal right now. used to form the perfect The carpenter has tenses worked well. have used with the infinitive I had to work that day. to indicate some kind of obligation used to form the He doesn’t work at all. -

The Production of Finite and Nonfinite Complement Clauses by Children with Specific Language Impairment and Their Typically Developing Peers

The Production of Finite and Nonfinite Complement Clauses by Children With Specific Language Impairment and Their Typically Developing Peers Amanda J. Owen University of Iowa, Iowa City The purpose of this study was to explore whether 13 children with specific language Laurence B. Leonard impairment (SLI; ages 5;1–8;0 [years;months]) were as proficient as typically developing age- and vocabulary-matched children in the production of finite and Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN nonfinite complement clauses. Preschool children with SLI have marked difficulties with verb-related morphology. However, very little is known about these children’s language abilities beyond the preschool years. In Experiment 1, simple finite and nonfinite complement clauses (e.g., The count decided that Ernie should eat the cookies; Cookie Monster decided to eat the cookies) were elicited from the children through puppet show enactments. In Experiment 2, finite and nonfinite complement clauses that required an additional argument (e.g., Ernie told Elmo that Oscar picked up the box; Ernie told Elmo to pick up the box) were elicited from the children. All 3 groups of children were more accurate in their use of nonfinite complement clauses than finite complement clauses, but the children with SLI were less proficient than both comparison groups. The SLI group was more likely than the typically developing groups to omit finiteness markers, the nonfinite particle to, arguments in finite complement clauses, and the optional complementizer that. Utterance-length restrictions were ruled out as a factor in the observed differences. The authors conclude that current theories of SLI need to be extended or altered to account for these results. -

Verbnet Guidelines

VerbNet Annotation Guidelines 1. Why Verbs? 2. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource 3. VerbNet Contents a. The Hierarchy b. Semantic Role Labels and Selectional Restrictions c. Syntactic Frames d. Semantic Predicates 4. Annotation Guidelines a. Does the Instance Fit the Class? b. Annotating Verbs Represented in Multiple Classes c. Things that look like verbs but aren’t i. Nouns ii. Adjectives d. Auxiliaries e. Light Verbs f. Figurative Uses of Verbs 1 Why Verbs? Computational verb lexicons are key to supporting NLP systems aimed at semantic interpretation. Verbs express the semantics of an event being described as well as the relational information among participants in that event, and project the syntactic structures that encode that information. Verbs are also highly variable, displaying a rich range of semantic and syntactic behavior. Verb classifications help NLP systems to deal with this complexity by organizing verbs into groups that share core semantic and syntactic properties. VerbNet (Kipper et al., 2008) is one such lexicon, which identifies semantic roles and syntactic patterns characteristic of the verbs in each class and makes explicit the connections between the syntactic patterns and the underlying semantic relations that can be inferred for all members of the class. Each syntactic frame in a class has a corresponding semantic representation that details the semantic relations between event participants across the course of the event. In the following sections, each component of VerbNet is identified and explained. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource VerbNet is a lexicon of approximately 5800 English verbs, and groups verbs according to shared syntactic behaviors, thereby revealing generalizations of verb behavior. -

TAV of English Finite Verb Phrase

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, July 2018, Vol. 8, No. 7, 1126-1130 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2018.07.019 D DAVID PUBLISHING TAV of English Finite Verb Phrase Peter Lung-shan CHUNG University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China It is widely known that a finite verb phrase (fVP) of a clause in English consists of three components: tense, aspect and voice. While the two tenses, present and past, and the two voices, active and passive, are recognized and generally agreed, the number and constituents of aspects may not be so simple and they are open to dispute. This paper proposes that a new aspect, the “modal” aspect, be included in addition to the commonly recognized ones, namely “simple”, “perfect” and “continuous” (also known as “progressive”). With the inclusion of the “modal” aspect, there are four single aspects: “simple”, “modal”, “perfect” and “continuous”. They can be combined to form multiple aspects according to the aforesaid sequence. The “modal” aspect is realized with a modal verb (any ofthe modal verbs will/would, shall/should, can/could, may/might, must, ought to, used to and the two semi-modals, “need” and “dare” in interrogative and negative structures). Whenever a modal verb is used, the verb phrase is in the modal aspect. The modal verb to be used is for the interlocutor to decide and falls beyond this discussion, which focuses on the structure of the fVP of the English language. The two tenses, eight aspects and two voices (active and passive) make up the 32 TAVs (an acronym formed with “Tense”, “Aspect” and “Voice”) of the English fVP. -

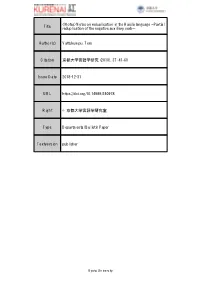

Title <Notes>Notes on Reduplication in the Haisla Language --Partial

<Notes>Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language --Partial Title reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb-- Author(s) Vattukumpu, Tero Citation 京都大学言語学研究 (2018), 37: 41-60 Issue Date 2018-12-31 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/240978 Right © 京都大学言語学研究室 Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 京都大学言語学研究 (Kyoto University Linguistic Research) 37 (2018), 41 –60 Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language Ü Partial reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb Ü Tero Vattukumpu Abstract: In this paper I will point out that, according to my data, a plural form of the negative auxiliary verb formed by means of partial reduplication exists in the Haisla language in contrary to a description on the topic in a previous study. The plural number of the subject can, and in many cases must, be indicated by using a plural form of at least one of the components of the predicate, i.e. either an auxiliary verb (if there is one), the semantic head of the predicate or both. Therefore, I have examined which combinations of the singular and plural forms of the negative auxiliary verb and different semantic heads of the predicate are judged to be acceptable by native speakers of Haisla. My data suggests that – at least at this point – it seems to be impossible to make convincing generalizations about any patterns according to which the acceptability of different combinations could be determined *. Keywords: Haisla, partial reduplication, negative auxiliary verb, plural, root extension 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to introduce some preliminary notes about reduplication in the Haisla language from a morphosyntactic point of view as a first step towards a better understanding and a more comprehensive analysis of all the possible patterns of reduplication in the language. -

The Complexities of the Welsh Copula

The complexities of the Welsh copula Bob Borsley University of Essex and Bangor University Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar University of Bucharest Stefan Muller,¨ Petya Osenova (Editors) 2019 CSLI Publications pages 5–25 http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/HPSG/2019 Keywords: copula, syntax-morphology mismatches, Welsh Borsley, Bob. 2019. The complexities of the Welsh copula. In Muller,¨ Stefan, & Osenova, Petya (Eds.), Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Head- Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, University of Bucharest, 5–25. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Abstract The Welsh copula has a complex set of forms reflecting agreement, tense, polarity, the distinction between main and complement clauses, the presence of a gap as subject or complement, and the contrast between predicative and equative interpretations. An HPSG analysis of the full set of complexities is possible given a principle of blocking, whereby constraints with more specific antecedents take precedence over constraints with less specific antecedents, and a distinction between morphosyntactic features relevant to syntax and morphosyntactic features relevant to morphology. 1. Introduction It is probably a feature of most languages that the copula is more complex in various ways than standard verbs. This is true in English, and it is very definitely true in Welsh. The Welsh copula has a complex set of forms reflecting agreement, tense, polarity, the distinction between main and complement clauses, the presence of a gap as subject or complement, and the contrast between predicative and equative interpretations. In this paper, I will set out the facts and develop an analysis within the Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG) framework. -

Word Order and Information Structure in Finite Verb Clauses in Hellenistic Period Hebrew by Andrew R. Jones a Thesis Submitted I

Word Order and Information Structure in Finite Verb Clauses in Hellenistic Period Hebrew by Andrew R. Jones A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Andrew R. Jones (2015) Word Order and Information Structure in Finite Verb Clauses in Hellenistic Period Hebrew Ph.D. 2015 Andrew R. Jones Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto This study investigates the relationship between word order and information structure in finite verb clauses in four ancient Hebrew texts from among the Dead Sea Scrolls—the Community Rule, the War Rule, and the Habakkuk Pesher. An excursus provides a separate treatment of Daniel 8–12. The theoretical linguistic foundations of the study are rooted in generative linguistics, especially the work of J. Uriagereka and N. Erteschik-Shir. The Early Immediate Constituent Theory of J. Hawkins also plays an important role. The emphasis is on syntactic structures where word order is flexible in order to investigate the effect of variation on information structure. The basic word order of subject and verb is indeterminate, and therefore it is not possible to know whether SV or VS order is marked (although the tendencies of each order are nonetheless clear). However, it is simple to determine that the basic word order of verb and object is VO. Deviations from the basic VO order can be explained using three structures: left-dislocation of a shift topic; fronting of a Topic (whether a shift topic, contrastive constituent, or restrictive constituent); and fronting of a non-Topic (whether a cleft constituent or a constituent that opens the clause-final attentive focus position for a different constituent). -

4 the Sentence, Auxiliary Verbs, and Recursion

Introduction to Configurational Syntax Chapter 4 : Chapter 4. 4 The Sentence, Auxiliary Verbs, and Recursion 4.1 Introduction In this chapter the sentence and the verb (predicate) phrase whose head is an auxiliary verb are formally introduced. These two categories do not appear to follow the universal expansion of XP proposed in Chapter 2. In the Principles and Parameters framework of syntax the structure of the sentence can be shown to fol- low the universal expansion of XP. However, the analysis of the sentence given the category CP1 is considered too complex to be covered here. The analyses given here follow the earlier standard views on the structure of the sentence. 4.2 The Sentence At first glance, note that the sentence contains a NP and a VP: (297)a. The moon orbits around the earth. b. [NP the moon ] [VP orbits around the earth ]. We can state the expansion of S (sentence) as: (298) The Expansion of S [1] S ˘ NP VP. The structure for (297 is: (299) [S [NP The moon ] [VP orbits around the earth]] Up to this point we have claimed that all constituents contain a head and a complement. If this is the case then what is the head of S? In advanced work it can be shown to be either tense in some points of view, or the verb in other points of view. In some sense both points of view or correct; however, it is too complex a matter to attempt to explain this here. We will adopt the above expansion, which is traditional and found in most texts, and note that the verb is the unexplained head of the sentence. -

Verb Phrase, Or VP

VP Study Guide In the Logic Study Guide, we ended with a logical tree diagram for WANT (BILL, LEAVE (MARY)), in both unlabelled: WANT BILL LEAVE MARY and labelled versions: P WANT BILL P LEAVE MARY We remarked that one could label the Predicate and Argument nodes as well, and that it was common to use S instead of P to label propositions in such logical tree structures in linguistics. It is also com- mon, in practice, to use V to label Predicates, and N (or NP, standing for Noun Phrase) to label Ar- guments. This would produce the following diagram: S V NP NP Subject Formation WANT BILL S V NP LEAVE MARY Note that, while these two predicates are in fact verbs, and the arguments are nouns, that’s not always the case, and one may use V loosely to label any Predicate node, whatever its syntactic class might be. This kind of structural description, intermediate between logic and surface syntax, is called a deep structure; we say this diagram represents the deep structure of Bill wants Mary to leave. Roughly speaking, deep structures are intended to represent the meaning of the sentence, stripped to its essentials. The deep structures are then related to the actual sentence by a series of relational rules. For instance, one such rule is that in English, there must be a subject NP, and it precedes the verb, instead of coming after it, as here. So we relate this structure with the following one by a rule of Subject Formation, which applies to every deep structure towards the end of the derivation (the series of rule applications; a number of other rules would have already applied earlier, producing the other differences). -

Animacy in Sentence Processing Across Languages: an Information-Theoretic Prospective

ANIMACY IN SENTENCE PROCESSING ACROSS LANGUAGES: AN INFORMATION-THEORETIC PROSPECTIVE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zhong Chen August 2014 c 2014 Zhong Chen ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ANIMACY IN SENTENCE PROCESSING ACROSS LANGUAGES: AN INFORMATION-THEORETIC PROSPECTIVE Zhong Chen, Ph.D. Cornell University August 2014 This dissertation is concerned with different sources of information that affect human sentence comprehension. It focuses on the way that syntactic rules in- teract with non-syntactic cues in real-time processing. It develops the idea first introduced in the Competition Model of MacWhinney in the late 1980s such that the weight of a linguistic cue varies among languages. The dissertation addresses this problem from an information-theoretic prospective. The proposed Entropy Reduction metric (Hale, 2003) combines corpus-retrieved attestation frequencies with linguistically-motivated gram- mars. It derives a processing asymmetry called the Subject Advantage that has been observed across languages (Keenan & Comrie, 1977). The modeling re- sults are consistent with the intuitive structural expectation idea, namely that subject relative clauses, as a frequent structure, are easier to comprehend. How- ever, the present research takes this proposal one step further by illustrating how the comprehension difficulty profile reflects uncertainty over different ini- tial substrings. It highlights particular disambiguation -

The Auxiliary Verb

THE AUXILIARY VERB Recognize an auxiliary verb when you find one. Every sentence must have a verb. To depict doable activities, writers use action verbs. To describe conditions, writers choose linking verbs. Sometimes an action or condition occurs just once—bang!—and it is over. Nate stubbed his toe. He is miserable with pain. Other times, the activity or condition continues over a long stretch of time, happens predictably, or occurs in relationship to other events. In these instances, a single-word verb like stubbed or is cannot accurately describe what happened, so writers use multipart verb phrases to communicate what they mean. As many as four words can comprise a verb phrase. A main or base verb indicates the type of action or condition, and auxiliary— or helping—verbs convey the other nuances that writers want to express. Read these three examples: Sherylee smacked her lips as raspberry jelly dripped from the donut onto her white shirt. Sherylee is always dripping something. Since Sherylee is such a klutz, she should have been eating a cake doughnut, which would not have stained her shirt. In the first sentence, smacked and dripped, single-word verbs, describe the quick actions of both Sherylee and the raspberry jelly. Since Sherylee has a pattern of messiness, is dripping communicates the frequency of her clumsiness. The auxiliary verbs that comprise should have been eating and would have stained express not only time relationships but also criticism of Sherylee's actions. 1 Below are the auxiliary verbs. You can conjugate be, do, and have; the modal auxiliaries, however, never change form.