The Boreal Forest Study: Finding Exceptional Protected Area Sites in the Boreal Ecozone That Could Merit World Heritage Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mr. Pavel Sulyandziga

Mr. Pavel Sulyandziga Nationality: Udege (Russia) Occupation: First Vice-President of RAIPON UNPFII Portfolio: Economic and Social Development, Environment EDUCATION · 1984 - Khabarovsk State Pedagogical Institute - Teacher of Mathematics · 1985 - Courses for the Higher Pedagogical Staff · 1986-89 - University of Marxism-Leninism, Legislation Department, Thesis on National Policy in the Modern Society PROFESSIONAL CAREER · 1984- 1987 Teacher of Mathematics, settlement of Krasny Yar, Primorsky Kray · 1985 -1987 School Deputy Director · 1987 - 1991 Chairman of the Executive Committee of Rural Council (Krasny Yar settlement) · 1991 - 1994 Chairman of the National Rural Council (Far East) · 1991- present Chairman of the Indigenous Peoples Association of the Primorsky Kray · 1994 - 1997 Councillor to the Governor of the Primorsky Kray on Indigenous Issues · 1997 - present Vice-President of the RAIPON · 2001 – present First Vice-President of the RAIPON OTHER ACTIVITIES International cooperation · 1991 -1993 participated in the Eurasian Club (Japan) activity - assistance to the education and preservation of culture of indigenous peoples · 1993 - Visited Indian reservations in the USA (California, Oregon, Washington) to study the experience on education, culture and self-governance · 1993 -1994 Participated in the elaboration of the project on biodiversity preservation in the Bikin river valley, responsible for the project implementation and direction. The project funded by the US State Department and US Federal Forest Service. · 1994 - 1995 -

Rock Art Studies: a Bibliographic Database Page 1 800 Citations: Compiled by Leigh Marymor 04/12/17

Rock Art Studies: A Bibliographic Database Page 1 800 Citations: Compiled by Leigh Marymor 04/12/17 Keywords: Peterborough, Canada. North America. Cultural Adams, Amanda Shea resource management. Conservation and preservation. 2003 Reprinted from "Measurement in Physical Geography", Visions Cast on Stone: A Stylistic Analysis of the Occasional Paper No. 3, Dept. of Geography, Trent Petroglyphs of Gabriola Island, BCMaster/s Thesis :79 pgs, University, 1974. Weathering. University of British Columbia. Cited from: LMRAA, WELLM, BCSRA. Keywords: Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada. North America. Stylistic analysis. Marpole Culture. Vision. Alberta Recreation and Parks Abstract: "This study explores the stylistic variability and n.d. underlying cohesion of the petroglyphs sites located on Writing-On-Stone Provincial ParkTourist Brochure, Alberta Gabriola Island, British Columbia, a southern Gulf Island in Recreation and Parks. the Gulf of Georgia region of the Northwest Coast (North America). I view the petroglyphs as an inter-related body of Keywords: WRITING-ON-STONE PROVINCIAL PARK, ancient imagery and deliberately move away from (historical ALBERTA, CANADA. North America. "THE BATTLE and widespread) attempts at large regional syntheses of 'rock SCENE" PETROGLYPH SITE INSERT INCLUDED WITH art' and towards a study of smaller and more precise PAMPHLET. proportion. In this thesis, I propose that the majority of petroglyphs located on Gabriola Island were made in a short Cited from: RCSL. period of time, perhaps over the course of a single life (if a single, prolific specialist were responsible for most of the Allen, W.A. imagery) or, at most, over the course of a few generations 2007 (maybe a family of trained carvers). -

Zarif, Ansarullah Official Hold Talks in Oman

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 16 Pages Price 40,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 39th year No.13563 Wednesday DECEMBER 25, 2019 Dey 4, 1398 Rabi’ Al thani 28, 1441 Top commander felicitates Expediency Council still Stramaccioni, Congratulations on birth anniversary of evaluating FATF-related Esteghlal; an unsolved the birth anniversary of Jesus Christ to all Jesus Christ 2 bills 2 problem 15 monotheists in the world Iran, India to expand transit co-op through Chabahar port TEHRAN – Iranian Transport and Urban between Iran and India has been followed Zarif, Ansarullah official Development Minister Mohammad Esla- in a variety of aspects and a number of new mi and Indian Minister of External Affairs agreements have been reached, the most Subrahmanyam Jaishankar met on Monday important of which were in transportation in Tehran to discuss expansion of transport and transit with Chabahar in focus. and transit cooperation between the two In the past few years, the development countries, especially through Chabahar port. of Chabahar port has been pursued very Speaking to the press after the meet- seriously, so that trade activities in the hold talks in Oman ing, the Iranian minister noted that the port have more than tripled in the past See page 2 development of economic cooperation two years, according to Eslami. 4 Tehran rejects Reuters’ claim on unrest death toll TEHRAN — An official at Iran’s Supreme accusations is basically very easy,” he National Security Council (SNSC) has said, describing the act as a psychological denied a claim by Reuters that said the operation against the Islamic Republic. -

Final Report

Final Report - Quebec Lower North Shore- Labrador Straits Regional Collaboration Workshop November 22, 2014 Quebec Lower North Shore-Labrador Straits Final Report Regional Development Workshop List of acronyms ATR: Association touristique régionale CEDEC: Community Economic Development and Employability Corporation CLD: Centre local de développement CRRF: Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation FFTNL: Fédération des francophones de Terre-Neuve et du Labrador LNS: Lower North Shore MNL: Municipalities Newfoundland and Labrador MUN: Memorial Univeristy of Newfoundland MRC: Municipalité Régionale de Comté NL: Newfoundland and Labrador OSSC: Organizational Support Services Co-operative QC: Québec QLNS-LS: Québec Lower North Shore-Labrador Straits RED Boards: Regional Economic Development Boards RDÉE TNL: Réseau de développement économique et d’employabilité de Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador UQAR: Université du Québec à Rimouski Page 2 of 42 Quebec Lower North Shore-Labrador Straits Final Report Regional Development Workshop Executive summary The Quebec Lower North Shore-Labrador Straits regional development workshop took place on October 14-16 2014 in Blanc Sablon (Québec) and L’Anse-au-Clair (Newfoundland and Labrador). The objective of this 2-day workshop was to learn from other jurisdictions on cross-boundary collaboration challenges, opportunities, and lessons learned; to assess and identify the local and regional contexts and priorities; and finally to explore and identify potential strategies and actors for moving forward with collaboration -

Neruské Národy Ruskej Federácie, Ich Etnonymá a Transliterácia

Neruské národy Ruskej federácie, ich etnonymá a transliterácia Viktória BALLOVÁ Neruské národy Ruskej federácie Hneď na úvod je nevyhnutné definovať si pojmy, s ktorými budeme v tejto analýze operovať - pojmy „národ“ a „neruský“. Národ je spoločenstvo ľudí, väčšinou rovnakého antropologického typu, ktorých spája rovnaká história, jazyk, kultúra a zvyky. Kvôli správnemu chápaniu slova „neruský“, je potrebné priblížiť si pojem „ruský“ (podrobnejšie napr. Guzi, 2008, 85-87). Na celom svete žije okolo 150 miliónov východoslovanského etnika – národa, známeho ako Rusi. V Ruskej federácii predstavujú okolo 116 miliónov obyvateľstva, čo je asi 79,8 % celkového obyvateľstva štátu (zo 150 miliónov). Najviac Rusov žije v centrálnej časti, na Severozápade krajiny a na Urale. Rozlišujeme dva hlavné dialekty ruského jazyka - severný (okajúci) a južný (akajúci). Ruský národ zastrešuje veľké množstvo malých národov ako napríklad Gorjuny, Garany, Kazaki (skôr kozácky subetnos), Kamčadaly, Kolymčane, Russoustinci, Markovci, Keržaki, Molokane atď (Itogi, 2000, 38). Dorozumievajú sa ruským jazykom, ktorý sa zaradzuje do východnej podskupiny, slovanskej skupiny indoeurópskej jazykovej rodiny. V kontexte nášho pojednania sa vyhneme charakteristike imigrantov a obyvateľov okolitých štátov, ktorý žijú aj na tomto území ako napr. Ukrajinci, Kazachovia, Litovčania, Gruzínci, nakoľko nie sú štátotvornou národnosťou Ruskej federácie. Podľa sčítania ľudu z roku 2002 prebýva na území Ruskej federácie okolo 180 národov. Unikátne, kultúrne i historicky bohaté etniká, ktoré tvoria približne 20% celkového obyvateľstva, ostávajú pre verejnosť takmer zabudnuté. Títo ľudia hovoria jazykmi 13-tich jazykových rodín (Abcházsko-adygejskej, Nachsko-dagestanskej, Kartveľskej, Uralskej, Altajskej, Jenisejskej, Jukagirsko-čuvanaskej, Čukotsko-kamčatskej, Aleutskej, Ajnskej, Semitskej, Sino-tibetskej, Austro-ázijskej) a Nivchskím jazykom, ktorý je považovaný za izolovaný (Guzi, 2009, s. -

Asatiwisipe Aki Management Plan – Poplar River First Nation

May 2011 ASATIWISIPE AKI MANAGEMENT PLAN FINAL DRAFT May, 2011 Poplar River First Nation ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND SPECIAL THANKS benefit of our community. She has been essential to documenting our history and traditional use and occupancy. The most important acknowledgement goes to our ancestors who loved and cherished this land and cared for it for centuries to ensure all Thanks go to the Province of Manitoba for financial assistance and to future generations would have life. Their wisdom continues to guide us the staff of Manitoba Conservation for their assistance and support. today in our struggles to keep the land in its natural beauty as it was created. We are very grateful to all of our funders and particularly to the Metcalf Foundation for its support and for believing in the importance of a The development and completion of the Asatiwisipe Aki Lands Lands Management Plan for our community. We would also like to thank Management Plan has occurred because of the collective efforts of many. the Canadian Boreal Initiative for their support. Our Elders have been the driving force for guidance, direction and motivation for this project and it is their wisdom, knowledge, and Meegwetch experience that we have captured within the pages of our Plan. Our Steering Committee of Elders, youth, Band staff and Council, and other community members have worked tirelessly to review and provide Poplar River First Nation feedback on the many maps, text and other technical materials that have Land Management Plan Project been produced as part of this process. Community Team Members We, the Anishinabek of Poplar River First Nation, have been fortunate Thanks go to the following people for their time, energy and vision. -

National Park System Plan

National Park System Plan 39 38 10 9 37 36 26 8 11 15 16 6 7 25 17 24 28 23 5 21 1 12 3 22 35 34 29 c 27 30 32 4 18 20 2 13 14 19 c 33 31 19 a 19 b 29 b 29 a Introduction to Status of Planning for National Park System Plan Natural Regions Canadian HeritagePatrimoine canadien Parks Canada Parcs Canada Canada Introduction To protect for all time representa- The federal government is committed to tive natural areas of Canadian sig- implement the concept of sustainable de- nificance in a system of national parks, velopment. This concept holds that human to encourage public understanding, economic development must be compatible appreciation and enjoyment of this with the long-term maintenance of natural natural heritage so as to leave it ecosystems and life support processes. A unimpaired for future generations. strategy to implement sustainable develop- ment requires not only the careful manage- Parks Canada Objective ment of those lands, waters and resources for National Parks that are exploited to support our economy, but also the protection and presentation of our most important natural and cultural ar- eas. Protected areas contribute directly to the conservation of biological diversity and, therefore, to Canada's national strategy for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity. Our system of national parks and national historic sites is one of the nation's - indeed the world's - greatest treasures. It also rep- resents a key resource for the tourism in- dustry in Canada, attracting both domestic and foreign visitors. -

The Quality of Animal Habitats Estimated from Track Activity and Remote Sensing Data a B B A

ISSN 1995-4255, Contemporary Problems of Ecology, 2009, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 176–184. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2009. Original Russian Text © A.S. Zheltukhin, Yu.G. Puzachenko, R.B. Sandlerskii, 2009, published in Sibirskii Ekologicheskii Zhurnal, 2009, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 341–351. The Quality of Animal Habitats Estimated from Track Activity and Remote Sensing Data a b b A. S. Zheltukhin , Yu. G. Puzachenko , and R. B. Sandlerskii aCentral Forest State Natural Biospheric Reserve, POB Zapovednik, Nelidovo Raion, Tver Oblast, 172513 Russia bSevertsov Institute of Problems of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninskii pr. 33, Moscow, 119071 Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—A method is proposed for estimating the quality of animal habitats from field counts with positioning routes and tracks by means of GPS, multi-channel remote sensing Landsat data, digital elevation model, and discriminant analysis. The distribution of American and European minks is analyzed to demonstrate the principle of choosing an optimal method for analyzing the environmental characteristics that determine the distribution of species and for mapping and estimating the quality of habitats and the probability of track detection. Outlooks and some problems of implementation of the proposed approach are discussed. DOI: 10.1134/S1995425509030035 Key words: habitat, track activity, remote sensing data, mustelids The estimation of habitat quality is a traditional eco- models opens new ways to study relationships between logical problem. Habitat implies a joint action of eco- species and environmental conditions as well as to esti- logical factors determining the level of population or mate habitat quality. The multichannel remote informa- the state of species population on some territory, i.e., tion transfers, either directly or indirectly, various ecological niche [1]. -

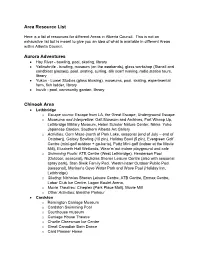

Area Resource List

Area Resource List Here is a list of resources for different Areas in Alberta Council. This is not an exhaustive list but is meant to give you an idea of what is available in different Areas within Alberta Council. Aurora Adventures • Hay River - bowling, pool, skating, library • Yellowknife - bowling, museum (on the weekends), glass workshop (Stencil and sandblast glasses), pool, skating, curling, silk scarf making, radio station tours, library • Yukon - Lumel Studios (glass blowing), museums, pool, skating, experimental farm, fish ladder, library • Inuvik - pool, community garden, library Chinook Area • Lethbridge o Escape rooms: Escape from LA, the Great Escape, Underground Escape o Museums and Interpretive: Galt Museum and Archives, Fort Whoop Up, Lethbridge Military Museum, Helen Schuler Nature Center, Nikka Yuko Japanese Garden, Southern Alberta Art Gallery o Activities: Corn Maze (north of Park Lake, seasonal (end of July – end of October)), Galaxy Bowling (10 pin), Holiday Bowl (5 pin), Evergreen Golf Centre (mini-golf outdoor + go-karts), Puttz Mini-golf (indoor at the Movie Mill), Elizabeth Hall Wetlands, Wear’m’out indoor playground and cafe o Swimming Pools: ATB Centre (West Lethbridge), Henderson Pool (Outdoor, seasonal), Nicholas Sheran Leisure Centre (also with seasonal spray park), Stan Siwik Family Pool, Westminster Outdoor Public Pool (seasonal), Mariner’s Cove Water Park and Wave Pool (Holiday Inn, Lethbridge) o Skating: Nicholas Sheran Leisure Centre, ATB Centre, Enmax Centre, Labor Club Ice Centre, Logan Boulet Arena, -

Central Sikhote-Alin

WHC Nomination Documentation File Name: 766rev.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND THE NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Central Sikhote-Alin DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 16th December 2001 STATE PARTY: RUSSIAN FEDERATION CRITERIA: N (iv) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 25th Session of the World Heritage Committee The Committee inscribed Central Sikhote-Alin on the World Heritage List under criterion (iv): Criterion (iv): The nominated area is representative of one of the world's most distinctive natural regions. The combination of glacial history, climate and relief has allowed the development of the richest and most unusual temperate forests in the world. Compared to other temperate ecosystems, the level of endemic plants and invertebrates present in the region is extraordinarily high which has resulted in unusual assemblages of plants and animals. For example, subtropical species such as tiger and Himalayan bear share the same habitat with species typical of northern taiga such as brown bear and reindeer. The site is also important for the survival of endangered species such as the scaly-sided (Chinese) merganser, Blakiston's fish-owl and the Amur tiger. This serial nomination consists of two protected areas in the Sikhote- Alin mountain range in the extreme southeast of the Russian Federation: NAME LOCATION AREA Sikhote-Alin Nature Preserve Terney District 401,428 ha Goralij Zoological Preserve Coastal zone on the Sea of Japan, N of Terney 4,749 ha The Committee encouraged the State Party to improve management of the Bikin River protected areas (Bikin Territory of Traditional Nature Use and Verkhnebikinski zakaznik) before nominating it as an extension. -

KEC Update We Believe in Excellence, Respect, Citizenship, Safety and Responsibility

Spring/Summer Edition June 2014 KEC Update We Believe in Excellence, Respect, Citizenship, Safety and Responsibility Kildonan-East Collegiate River East Transcona School Division 845 Concordia Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba R2K 2M6 Provincial Announcement at KEC Phone: 204-667-2960 The Autobody Paint Shop at Kildonan-East Collegiate was the site of a major provincial funding announcement on May 27th . Principal Diana Posthumus Premier Greg Selinger was on hand to announce that the province is making a $30 million investment to upgrade technical training facilities Vice-Principals used to train high school students, to help meet the growing demand for Rob Hadath skilled workers in Manitoba. Don Kupiak Darlene Martineau “Providing more opportunities for young Manitobans to transition from high school into good jobs is critical as we work toward our ambitious target of Attendance Line adding 75,000 more workers by 2020,” says Premier Selinger. 204-669-6036 Technical training facilities give students opportunities to learn on cutting- RETSD Board of Trustees edge equipment, earn high school credits and enable work placements and participation in the High School Apprenticeship Program. Robert Fraser 204-667-9348 “Speaking on behalf of all Manitoba school divisions, we welcome and (Chair) appreciate the additional funding announced by the province today. (Ward 3 for KEC) High school students throughout Manitoba will benefit greatly from the Colleen Carswell enhanced technical training facilities, which will translate into good jobs 204-222-1486 -

CHURCHILL POLAR BEARS Activity Level: 2 October 25, 2021 – 7 Days

CHURCHILL POLAR BEARS Activity Level: 2 October 25, 2021 – 7 Days 3 nights in Churchill with 2 expeditions in 14 Meals Included: 5 breakfasts, 4 lunches, 5 dinners the Tundra Buggy to watch polar bears Fares per person: $8,845 double/twin; $10,385 single Experience one of the world’s most Please add 5% GST. wonderful natural phenomena — the Early Bookers: annual polar bear migration on the coast of $200 discount if you book by April 30, 2021. Hudson Bay. The world’s largest polar bear Experience Points: denning area is 40 km southeast of Earn 155 points on this tour. Redeem 155 points if you book by June 23, 2021. Churchill and has been protected in Wapusk National Park. The bears occupy Departures from: BC Interior this area through the summer and early fall. Tundra Buggies by Hudson Bay With October’s snow and approaching winter, the polar bears start to migrate north to Churchill and wait for the ice to form on Hudson Bay where they spend the winter hunting seals. Therefore, late October and early November are the prime viewing weeks and polar bear sightings are at their peak. ITINERARY Day 1: Monday, October 25 Thule, and modern Inuit times. We stay three Flights are arranged from Kamloops, Kelowna, nights in Churchill (hotel name to be advised and Penticton to Winnipeg. Tonight, we stay at later). Tonight, a cultural presentation is arranged the Lakeview Signature Hotel near the airport, so with a local speaker. we are conveniently located for the early flight to Meals included: Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner Churchill on Wednesday.