Source Unit on Swine Production and Management Covered a "Broad Area of Problems Dealing with Swine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yorkshire Features to find out More About Yorkshire Breed Registration and Show Eligibility, Visit Nationalswine.Com

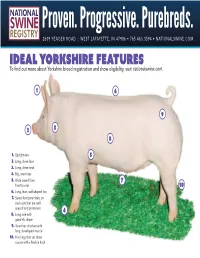

Proven. Progressive. Purebreds. 2639 YEAGER ROAD :: WEST LAFAYETTE, IN 47906 • 765.463.3594 • NATIONALSWINE.COM Ideal yorkshire Features To find out more about Yorkshire breed registration and show eligibility, visit nationalswine.com. 1 6 9 2 3 8 1. Upright ears 5 2. Long, clean face 3. Long, clean neck 4. Big, even toes 5. Wide based from 7 front to rear 10 6. Long, lean, well-shaped top 7. Seven functional teats on each side that are well spaced and prominent 4 8. Long side with good rib shape 9. Good hip structure with long, developed muscle 10. Hind legs that set down square with a flexible hock Yorkshire AMERICA’S MATERNAL BREED Yorkshire boars and gilts are utilized as Grandparents (GP) in the production of F1 parent stock females that are utilized in a ter- minal crossbreeding program. They are called “The Mother Breed” and excel in litter size, birth and weaning weight, rebreeding interval, durability and longevity. They produce F1 females that exhibit 100% maternal heterosis when mated to a Landrace. Yorkshire breeders have led the industry in utilization History of the Yorkshire Breed of the "STAGES™" genetic evaluation program. From Yorkshires are white in color and have erect ears. They are 1990-2006, Yorkshire breeders submitted over 440,000 the most recorded breed of swine in the United States growth and backfat records and over 320,000 sow and in Canada. They are found in almost every state, productivity records. This represents the largest source with the highest populations being in Illinois, Indiana, of documented performance records in the world. -

Oclc # Issn Title Imprint

Serial titles taken from The Literature of the Agricultural Sciences, Wallace C. Olsen, series editor OCLC # ISSN TITLE IMPRINT 11245385 A few hens Boston, Mass. : [I.S. Johnson & Co.], 1897-1902 12374891 A Stuffed club [Denver, Colo. : s.n., 1907- 1589859 0888-2479 A.M.A. archives of internal medicine Chicago, Ill : American Medical Association, c1950-c1960 436084535 A.P.A. progress Waynesville, Ohio : American Poultry Association 124045499 African beekeeping= Afrikaanse byeboerdery Port Shepstone : [s.n.], 1958-1959 726764166 Agricultural bulletin / National Association of Food Chains Washington, D.C. : The Association 1478526 0096-6681 Agricultural chemicals [Caldwell, N.J., etc., Industry Publications] 1478533 0002-1458 Agricultural engineering [St. Joseph, Mich., etc., American Society of Agricultural Engineers] 1692532 0096-6673 Agricultural news letter Wilmington, Del. : E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co 45878840 Agrimotor magazine Chicago, Ill. : Halliwell and Patton Pub. Co 1478600 0002-1962 Agronomy journal [Madison, Wis., etc., American Society of Agronomy] 1 9/14/2011 Serial titles taken from The Literature of the Agricultural Sciences, Wallace C. Olsen, series editor OCLC # ISSN TITLE IMPRINT 1479576 0002-7626 American bee journal [Hamilton, Ill., etc., Dadant & Sons] 11220544 American beef producer Denver, Colo. : American National Live Stock Association Pub. Co., 1969-1972 633268164 American Beekeeper New York. W.T. Falconer. 1892 1479582 American Berkshire record Springfield, Ill. : American Berkshire Association, 1876- 5234320 American blacksmith and motor shop Buffalo, N.Y. [1901-24] 2444606 0002-7723 American brewer [Kutztown, Pa., etc. American Brewer Pub. Corp.] 8326108 American brewers' review Chicago : [s.n 5323417 American butter & cheese review New York, Urner-Barry Pub. -

July 2016 Nuisance Case Update

www.iowapork.org The official publication of the Iowa Pork Producers Association Vol. 5253 NO. 4-56-7 MayJuly 2016 Nuisance Case update JULY 2016 1 2 JULY 2016 Table of Contents 05 Randomly Speaking – A message from the president 08 National Pork Board announces new CEO 12 New stained glass pork artwork unveiled at ISU 14 Eldon McAfee’s nuisance case update 16 Pork slider a tasty hit at IPPA Lawn Party 18 Strengthened efforts needed to prevent gastric ulcers in slaughter pigs 20 PQA Plus® revisions announced at World Pork Expo 21 Producers share audit experiences, advice at World Pork Expo 22 ISU economist bullish on exports to China 24 Producer optimism shines through at 2016 World Pork Expo About the Cover 26 NPPC honors industry leader ‘Pig’ Paul Pork producers continue to be targeted in nuisance cases and IPPA legal counsel 27 IPPA holds first Iowa Speedway promotion of season Eldon McAfee takes a look at the nuisance 28 ISU veterinarians find easier way to collect diagnostic case situation and what may lie ahead. Get the details on page 14. samples from pigs 29 Farm-to-Fork Week held in Webster City 30 2016 Iowa Pork Foundation scholarship winners 32 College students enhance education through IPPA internships Programs are made available to pork 33 86th Iowa General Assembly summary producers without regard to race, color, sex, religion or national origin. The Iowa 34 Continuous learning helps producers adjust Pork Producers Association is an equal opportunity employer. In Every Issue The Iowa Pork Producer is the official publication of the Iowa Pork Producers 06 Pork Industry Briefs Association and sent standard mail from 10 Iowa Pork Industry Center News Des Moines, Iowa, to Iowa pork producers by the first week of the month of issue. -

Pdf Download

Ideal Duroc Features To find out more about Duroc breed registration and show eligibility, visit nationalswine.com. 2 1 6 9 3 7 10 1. Long, clean face 2. Drooping ears 5 3. Long, clean neck 4. Big, even toes 5. Wide based from front to rear 8 6. Square, expressively muscled top 2639 YEAGER ROAD :: WEST LAFAYETTE, IN 47906 • 765.463.3594 NATIONALSWINE.COM 2639 YEAGER ROAD :: WEST LAFAYETTE, Proven. Progressive. Purebreds. Progressive. Proven. 7. Seven prominent, functional 11 teats on each side that are well spaced 4 8. Long side with good rib shape 9. Durably constructed frame 10. Long, deep muscular through all portions of the ham 11. Hind legs that set down square with a flexible hock Duroc THE WORLD'S TERMINAL SIRE Duroc sires are utilized most frequently as a Terminal/Paternal sire in a terminal cross-breeding program. They sire market pigs that excel in durability, growth, and muscle qualities attributes, and are competitive with oth- er industry sires for carcass leanness and feed efficiency. Duroc boars are the predominate Terminal sire used in the world and provide 100% heterosis when mated to Yorkshire x Landrace F1 females. Some systems utilize a com- mercial parent stock female that is 25% Duroc to improve robustness and longevity in their sow herds. breed potency in today's picture of swine improvement and History of the Duroc Breed holds forth inviting promise of future usefulness and value. Durocs are red pigs with drooping ears. They are the second Durocs were identified as a superior genetic source for most recorded breed of swine in the United States and a major improving eating qualities of pork in the recent National breed in many other countries, especially as a terminal sire or Pork Producers Council Terminal Sire Line Evaluation. -

Genetic Effects on Maternal, Growth and Carcass Traits of Swine Satjar Ravungsook Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1996 Genetic effects on maternal, growth and carcass traits of swine Satjar Ravungsook Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, Animal Sciences Commons, and the Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Ravungsook, Satjar, "Genetic effects on maternal, growth and carcass traits of swine " (1996). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 11564. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/11564 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfihn master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Breeds of Swine

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 11-1966 BREEDS OF SWINE Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BREEDS OF SWINE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA COUNTY EXTENSION OFFICE COURT HOUSE WI LBER, NEBRASKA 68465 Farmers Bulletin No. 1263 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE The purpose of this bulletin is to present the most important features of the principal breeds of swine in this country, and the relationship of purebreds to the commercial swine industry. For information regard ing the rules of registry and the issuance of herdbooks, or for lists of breeders, write to the individual associations. The officers and ad dresses of the breed-record associations change from time to time; hence they are not included in this bulletin. But, on request, the Animal Hus bandry Research Division, USDA, Beltsville, Md. 20705, will furnish the names and addresses of the secretaries of established associations as last reported. Although encouraging the development of improved types of swine and other livestock, the United States Department of Agriculture has no jurisdiction over the registration of animals or the operation of the re spective associations. Acknowledgement is made to swine record associations and breeders of purebred hogs, who furnished photographs of animals representative of present-day types. -

Breeds of Swine

Historic, archived document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. BREEDS OF SWINE F. G. ASHBROOK Animal Husbandry Division FARMERS' BULLETIN 765 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Contribution from the Bureau of Animal Industry A. D. MELVIN, Chief Washington, D. C# March, 1917 r I ^HERE are two distinct types of swine, the lard and the • bacon types. Swine of the lard type far outnumber those of the bacon type in the United States. The lard type is preferred by the people of this country, consequently the majority of feeders produce the rapid fattening, heavily fleshed lard type. The bacon type is not raised extensively in the United States. The production of choice bacon is more general in those countries where the feed of the hog is more varied and where com is not rehed upon as the principal grain for hogs. The principal breeds of the lard type are the Poland-China' Berkshire, Chester White, Duroc-Jersey, and Hampshire. The principal breeds of the bacon type are the Tamworth and the Large Yorkshire. There is no best breed of swine. Some breeds are superior to others in certain respects, and one breed may be better adapted than another to certain local conditions. This is a matter which the farmer will have to decide for himself. Infor- mation concerning the various breeds of swine, their origin, general appearance, development, and adaptabihty is given in the following pages. BREEDS OF SWINE. CONTENTS. Page. Page. Choosing a breed 3 The lard type of hog—Continued. Classification of swine 3 The Hampshire 10 The lard type of hog 4 The bacon type of hog 12 The Poland-China 5 The Tamworth 12 The Berkshire 6 The Large Yorkshire ' 13 The Duroo-Jersey 7 Minor breeds of hogs 14 The Chester White 9 CHOOSING A BREED. -

Raising Pigs

NATIONAL JUNIOR SWINE ASSOCIATION Raising pigs. Raising kids. Raising our MEMBER PACKET Dear National Junior Swine Association Member, Congratulations on becoming a member of the NJSA – one of the fastest growing and most exciting youth livestock organizations in the country! We have many great opportunities for you to gain knowledge, develop friendships and have fun in the NJSA! The NJSA was formally established in 2000 for youth, ages 21 and under, who have an interest in the purebred Duroc, Hampshire, Landra- ce and Yorkshire breeds of swine. The organization offers young people an opportunity to become further involved and informed about the industry, while meeting other youth that have the same passion. Throughout the year, NJSA puts on numerous swine shows and leadership conferences, along with providing scholarship and internship opportunities, just to name a few. NJSA has grown to over 12,500 members as of early 2016! We promote ethical values and practices in raising and showing hogs to our youth, along with maintaining and building the knowledge and experiences of past generations. You will not want to miss out on all of the leadership and involvement opportunities offered in the NJSA! NJSA past members speak about how much NJSA helped them find their closest friends and learn to open up and embrace who they are. Don't hold back from getting involved, you won't regret it! NJSA is present at twelve different shows throughout the year, all over the country. The NJSA hosts four regional shows (Eastern Re- gional-Hamburg, NY; Southwest Regional-Woodward, OK; Southeast Regional-Perry, GA; Western Regional-Turlock, CA), three na- tional shows (World Pork Expo Junior National-Des Moines, IA; National Junior Summer Spectacular-Louisville, KY; National Barrow Show-Austin, MN) and partners with five other national swine shows (American Royal-Kansas City, MO; North American International Livestock Exposition-Louisville, KY; National Western Stock Show-Denver, CO; Ak-Sar-Ben-Omaha, NE; Arizona Junior Nationals-Phoe- nix, AZ). -

Member Handbook

E STAGES Member Handbook LANDRAC CE REN NFE CO PE WORLD PORK EXPO TY ER DUR M OC M OGY SU NOL CH TE S & IC CLASSIC ET FALL N SR GE N L E ITT R ER I RE H CO S RD K IN R GS O Y E IR H S P M A H N O I T A I C O S S A E N I W S R O I N U J L E A G D N E O I K T C A O T N S D E E S About NSR History & Membership Demographics. Each of the respective breed associations that comprise the National Swine Registry have a long and rich history that goes back to the 1800s. During the time when each association operated as a separate entity, the general oversight and development of each breed was governed individually. In the earlier stages of the purebred seedstock industry in the U.S., breeders typically raised and sold one breed of hogs. Over time, these breeders began to take part in more than one organization, as the average seedstock supplier maintained several breeds on their farm to meet the demands of the U.S. commercial producer. As this trend increased throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s, an increase in the level of sophistication of commercial clients was also taking place. As the commercial clients of purebred seedstock suppliers began to utilize more specific crossbreeding programs, this ultimately placed increased pressure on the seedstock supplier, and ultimately, the needed services offered by breed organizations. -

The Pennsylvania Livestock Association's Hall of Fame

The Pennsylvania Livestock Association’s Hall of Fame Biographical Sketches Originally Compiled by Sharon M. Williams, 2001 Thanks to all of the inductees and their families who provided the information to complete this book. 2 63 to be active in the Dorset industry as a judge and flock consultant. Over the years he has been a consultant for many major Dorset flocks; helping with the management, care, showing and breeding decisions. In 2015 Dick was inducted into the Continental Dorset Hall of Fame. His influence can be seen in the sheep of many Pennsylvania flocks. 62 3 the high scoring individual in sheep judging at KILE. Following college, Dick spent two years with the United States Marines, proudly earning the rank of Sar- gent before returning home to PA. Dick succeeded Shaffner as shepherd at Penn State in February 1971 and continued the legacy of shepherding and high production flocks. He retired from Penn State in 2009 after 38 years. During his time, Dick bred and showed cham- pion sheep for Penn State at the many sheep shows and sales across the country with champions in Chicago and Louisville. One of the many highlights to his career was the 2005 show season. The Penn State Sheep Program attended seven sales throughout the country and were awarded the following champions: National Champion Ewe, 2 Supreme Champi- ons, 6 Grand Champions, 3 Reserve Grand Champions, 2 Junior Champions, and 3 Reserve Senior Champions. Additionally, receiving 3 Best Consignment Awards over all breeds! The Penn State Polled Dorset flock was undefeated that year at the Ohio State Fair, Indiana State Fair, Eastern States Exposition, and North American International Livestock Exposition. -

Teachers of Adult Vocational Education in Agriculture

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 256 CE 005 282 AUTHOR Vincent, Gary; Iverson, Maynard J. TITLE Profitable Hog Prcduction. An Instructional Unit for Teachers of Adult Vocational Education in Agriculture. INSTITUTION Kentucky Univ., Lexington. Div. of Vocational Education. SPONS AGENCY Kentucky State Dept. of Education, Frankfort. Bureau of Vocaticnal Education. REPORT NO VT-102-060 PUB DATE 73 NOTE 144p.; For related documents, see CE 005 271-281 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$6.97 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS *Adult Farmer Education; Adult Vocational Education; Agricultural Education; *Agricultural Production; Curriculum Guides; Instructional Materials; *Livestock; *Teaching Guides; Vocational Agriculture; *Young Farmer Education IDENTIFIERS *Hogs ABSTRACT Developed as a guide for teachers in planning and conducting classes in young or adult farmer education, the 10-lesson unit covers the basic areas of hog production; selection, breeding, feeding, managing, and marketing. The format used is designed to assist teachets in utilizing problem-solving and the discussion method of teaching. The appendix includes teaching forms and a unit evaluation questionnaire. (NJ) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. *********************************************************************** U.S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO. -

Swine Industry Directory

APPENDIX 1 Swine Industry Directory NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS American Association of Swine Practitioners 15921 Fleur Drive Des Moines, IA 50309 Thomas A. Neuzil, DVM, Executive Secretary American Feed Industry Association, Inc. 1501 Wilson Blvd., Suite llOO Arlington, V A 22209 Oakley M. Roy, President Organizational Purpose The national trade association representing feed manufacturers and suppliers to that indus try with the mission of helping to establish a favorable business climate for the industry. American Meat Institute P. o. Box 3556 Washington, DC 20007 J. Patrick Boyle, President Organizational Purpose To create a regulatory, legislative, and consumer environment in which the meat packing and processing industry can operate efficiently and profitably. The institute will provide programs and services to improve the industry's economic environment and to expand the industry's knowledge base through education and research. American Registry of Professional Animal Scientists Business Office: 309 W. Clark Street Champaign, IL 61820 Phone: (217) 356-3182 355 356 SWINE INDUSTRY DIRECTORY Monthly Publication: Professional Animal Scientist Organizational Purpose (1) To certify qualified members, (2) to strengthen Animal Science among the professions, and (3) to promote the profession of Animal Science. American Society of Animal Science Business Office: 309 W. Clark Street Champaign, IL 61820 Phone: (217) 356-3182 Robert B. Zimbelman, Executive Vice President c/o FASEB 9650 Rockville Pike Bethesda,MD 20814 Phone: (301) 571-1875 Monthly Publication: Journal of Animal Science Organizational Purpose To foster communication and collaboration among all individuals and entities associated with animal science research, education, industry, or governance to serve human needs. Midwest Plan Service 122 Davidson Hall Iowa State University Ames, IA 50011 Glenn A.