Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art ANANDA K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

Neidentificate 2020-324

Neidentificate 2020-324 ID Distributie Titlu piesa Autor Interpret Textier Producator Emisiune Spatiu emisie Orchestra Minute Secunde Executii Post 2020-324 Internet 106579948 Adanc In Moarte Adanc In Moarte Aprilie 2020 0 0 1 Oneros Orange.ro - Ian - Iunie 2020 2020-324 Internet 106579949 Adanc In Moarte Adanc In Moarte Februarie 2020 0 0 1 Oneros Orange.ro - Ian - Iunie 2020 2020-324 Internet 106579950 Adanc In Moarte Adanc In Moarte Ianuarie 2020 0 0 1 Oneros Orange.ro - Ian - Iunie 2020 2020-324 Internet Internet Orange - 106579951 Adanc In Moarte Adanc In Moarte Mai 2020 0 0 1 Orange.ro - Ian - Tv Go Iunie 2020 2020-324 Agentii Shield Agentii Shield - Internet 106579952 Cei Care Vor …cei Care Vor Ianuarie 2020 0 0 1 Oneros Orange.ro - Ian - Intra Aici Intra Aici Iunie 2020 2020-324 Agentii Shield Agentii Shield - Internet 106579953 Cei Care Vor …cei Care Vor Martie 2020 0 0 1 Oneros Orange.ro - Ian - Intra Aici Intra Aici Iunie 2020 2020-324 Agentii Shield Agentii Shield - Internet Internet Orange - 106579954 Cei Care Vor …cei Care Vor Mai 2020 0 0 1 Orange.ro - Ian - Tv Go Intra Aici Intra Aici Iunie 2020 2020-324 Internet Agentii Shield Agentii Shield - 106579955 Aprilie 2020 0 0 1 Oneros Orange.ro - Ian - Incheiere Incheiere Iunie 2020 2020-324 Internet Agentii Shield Agentii Shield - 106579956 Ianuarie 2020 0 0 1 Oneros Orange.ro - Ian - Incheiere Incheiere Iunie 2020 2020-324 Internet Agentii Shield Agentii Shield - 106579957 Aprilie 2020 0 0 1 Oneros Orange.ro - Ian - Inchisoarea Inchisoarea Iunie 2020 2020-324 Internet -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

The Ordinary Chants of the Office D

The Ordinary Chants of the Office THE COMMON TONES. At the beginning of the Hours. 1. The'f. Deusin adjutorium. is sung in the Festal tone {see Vespers, p. 250), at Matins, Lands, and Vespers, and also at Terce before Pontifical Mass. 2. It is sung in the Simple tone {see Compline, p. 263), at Prime, Terce, Sext, None, and Compline. 3. On very solemn feasts, at Vespers only, it may be sung as follows : t. 177-. >y. p, fc •• -a-^r+ D E-us in adjut6-ri- um me"- um intende. 1^. D6mine ad adju- 1 * p» a- 1 . s • * • • • • ?? •• 'v' vandum me festi-na. G16-ri- a Patri, et Fi-li-o, et Spi-ri-tu-i San- -•—• • -=-•- + cto. Sic-ut erat in pnncipi- o, et nunc, et semper, et in saecu-la 1—6—1_ •—•—!- u— •• i P '* -•—-•——•—•—•• i saecu-lo-rum. Amen. Alle-lu-ia. or : Laus tf-bi D6mine Rex aet^mae gl6-ri-ae. The Eight Tones of the Psalms. The first verse of a psalm is always intoned by the Cantor with the formula of intonation proper to each tone. The following verses begin on the dominant. This rule is observed at all the Hours, even in the Office for the Dead. This rule is applied also to the Psalms (or divisions of psalms) which are sung under one Antiphon, provided that each ends with the doxology Gloria The Tones of the Psalms. 113 Patri, the formula of intonation being repeated by the Cantor at the first verse of each Psalm or each division. -

Nouveautés - Mai 2019

Nouveautés - mai 2019 Animation adultes Ile aux chiens (L') (Isle of dogs) Fiction / Animation adultes Durée : 102mn Allemagne - Etats-Unis / 2018 Scénario : Wes Anderson Origine : histoire originale de Wes Anderson, De : Wes Anderson Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman et Kunichi Nomura Producteur : Wes Anderson, Jeremy Dawson, Scott Rudin Directeur photo : Tristan Oliver Décorateur : Adam Stockhausen, Paul Harrod Compositeur : Alexandre Desplat Langues : Français, Langues originales : Anglais, Japonais Anglais Sous-titres : Français Récompenses : Écran : 16/9 Son : Dolby Digital 5.1 Prix du jury au Festival 2 cinéma de Valenciennes, France, 2018 Ours d'Argent du meilleur réalisateur à la Berlinale, Allemagne, 2018 Support : DVD Résumé : En raison d'une épidémie de grippe canine, le maire de Megasaki ordonne la mise en quarantaine de tous les chiens de la ville, envoyés sur une île qui devient alors l'Ile aux Chiens. Le jeune Atari, 12 ans, vole un avion et se rend sur l'île pour rechercher son fidèle compagnon, Spots. Aidé par une bande de cinq chiens intrépides et attachants, il découvre une conspiration qui menace la ville. Critique presse : « De fait, ce film virtuose d'animation stop-motion (...) reflète l'habituelle maniaquerie ébouriffante du réalisateur, mais s'étoffe tout à la fois d'une poignante épopée picaresque, d'un brûlot politique, et d'un manifeste antispéciste où les chiens se taillent la part du lion. » Libération - La Rédaction « Un conte dont la splendeur et le foisonnement esthétiques n'ont d'égal que la férocité politique. » CinemaTeaser - Aurélien Allin « Par son sujet, « L'île aux chiens » promet d'être un classique de poche - comme une version « bonza? de l'art d'Anderson -, un vertige du cinéma en miniature, patiemment taillé. -

Richard Rufus of Cornwall on Creation: the Reception of Aristotelian Physics in the West

Richard Rufus of Cornwall on Creation: The Reception of Aristotelian Physics in the West REGA WOOD Richard Rufus was an English philosopher-theologian, the fifth Franciscan Master of Theology at Oxford.1 Like Bonaven- ture, he was Master of Arts at Paris before joining the Franciscans in 1238, five years before Bonaventure's entry and two years after the celebrated theologian Alexander of Hales had joined the order, bringing with him what became the order's first chair of theology. Together, Alexander of Hales, Robert Grosseteste, Bonaventure, and Richard Rufus helped make the Franciscan order a major force in the intellectual life of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.2 1. Thomas of Eccleston Tractatus de adventu fratrum mirwrum in Anφam, ed. A. G. Little (Manchester: University Press, 1951), p.5L 2. This paper is dedicated to the late James Weisheipl and to the late Frank Kelley, an esteemed collaborator on the Ockham edition at the Franciscan Institute. Fr. Weisheipl supervised Kelley's doctoral work and encouraged him to broaden his interests to include Franciscan as well as Dominican contributions to the history of Western philosophy. Work on this paper began in 1983 in Erfurt, East Germany, and in West Berlin. It was supported in part by an Alexander von Humboldt Fellowship and a grant from the American Philosophical Society. A preliminary version of this paper was read at Kalamazoo, Michigan, at the 1989 Medieval Congress. It was included in the sessions dedicated to James Weisheipl. i 2 REGA WOOD Rufus's influence was chiefly felt in England during the thirteenth century. -

Republic Lost

A post-apocalyptic future where Plato's "Republic" becomes terrifying reality. REPUBLIC LOST Order the complete book from the publisher Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/5581.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. YOUR FREE EXCERPT APPEARS BELOW. ENJOY! REPUBLIC LOST A Novel by J. Paul Rinnan Copyright © 2011 J. Paul Rinnan ISBN 978-1-61434-273-1 REPUBLIC LOST All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Cover art by Todd Engle Map art by S.C. Watson Illustration (www.oreganoproductions.com) Printed in the United States of America. The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2011 First Edition We are compelled by the truth to say that no city, constitution, or individual man will ever become perfect until some chance event compels those few philosophers who are not vicious to take charge of a city, whether they want to or not, and compels the city to obey them, or until a god inspires the present rulers and kings or their offspring with a true erotic love for true philosophy. Plato, Republic, 499b Every trace of anarchy should be utterly eradicated from all the life of men. Plato, Laws, 942d Give me the high eye To see like Kabiri, Fly up the dream heights Kissing eternal light. -

From William Golding's Lord of the Flies to ABC's LOST. By

Humanity Square One: From William Golding’s Lord of the Flies to ABC’s LOST. by Antonia Iliadou A dissertation to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki September 2013 Humanity Square One: From William Golding’s Lord of the Flies to ABC’s LOST. by Antonia Iliadou Has been approved September 2013 APPROVED: _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ Supervisory Committee ACCEPTED: _______________ Department Chairperson Iliadou 1 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................1 ABSTRACT...............................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1: William Golding’s Lord of the Flies: Analysis and Contextualization ..............1 1.1. a. Lord of the Flies in an age of ambiguity: The position of Golding’s novel in the Post War United States...........................................................................................................2 1.1. b. The Impact of Golding’s Lord of the Flies on its Readers........................................14 1.2. “… The picture of man, at once heroic and sick”: The Depiction -

Latin for Lawyers

LATIN FOR LAWYERS The Language of the Law By LAZAR EMANUEL J.D., Harvard Law School Published by Latin For Lawyers, 1st Edition (1999) Emanuel Publishing Corp. • 1328 Boston Post Road • Larchmont, NY 10538 Copyright © 1999 by LAZAR EMANUEL _____________________ ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. This book is not intended as a source of advice for the solution of legal matters or problems. For advice on legal matters, the reader should consult an attor- ney. ISBN 1-56542-499-9 PREFACE I have tried in this book to do several things. y To identify those words, phrases and axioms which still find their way in their original Latin into legal study and writing. y To identify all words and phrases in current English used by lawyers and derived from Latin y To trace the origin of the words and phrases by identifying and defining their Latin roots. y To define each entry in every sense in which it has meaning for lawyers. y To list in each definition appropriate references to such documents as the U.S. Constitution, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct, and other documents of concern to lawyers. My hope is that law students and lawyers will find this a useful tool for studying the origin, development and meaning of all legal words and terms which can be traced to Latin. -

Kane X. Faucher in Order to Better Address The

THE EFFECT OF THE ATOMIST CLINAMEN IN THE CONSTITUTION OF BORGES’S “LIBRARY OF BABEL” Kane X. Faucher n order to better address the problem of Borges’s famous Babe- Ilian library and how it is constituted, we must scale back and have recourse to the debates of antiquity between the finite Aris- totelian universe and the infinite “all” (pan) of the Greek Atomists. Moreover, we ought to consider the problem of the seemingly in- finite permutations of the texts in the Library of Babel, the diffu- sion of the librarians, and the architectural structure of the library itself according to our provisional assertion that these are a prod- uct of the atomistic clinamen (klynamen). Borges himself leaves the question suspended as to whether this library is indeed infinite or merely apparently so (a functional infinite that denotes our lack of seizing the entire library as a conceptual or dimensional whole). We will here (re)consider an Aristotelian version of the Library of Babel to place in higher relief the more dynamic and intriguing conception of the Library as having fidelity to an atomist cosmol- ogy. The thrust of our investigation will be to determine the role of the clinamen in the constitution of the Babelian library. Borges’s narrator effectively is forced to side with the atomist view of the library, a library that is indeed a biblio-chaosmoi. The issues under consideration will include the prospect of the library’s dimension- ality as either finite or infinite, a special case of motion to support both these views, contrasting the Aristotelian and atomist view- point. -

0062077.Pdf (771.4Kb)

Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Humanas UNIVERSIDAD TECNOLÓGICA DE BOLÍVAR PROYECTO DE TRABAJO DE GRADO Único formato aceptado por la Facultad IMPRIMA ESTA HOJA Y DILIGÉNCIELA A MANO PARA ADJUNTARLA SU PROYECTO Director de Diseño de Proyecto: Carlos Durango Aceptación del Director Diseño Proyecto: Fecha:___________________ Aprobación : ___________________ Aceptación Comité Curricular: Nombre y Firma: Fecha: __________________________________________________ - 1 – I. IDENTIFICACIÓN DEL PROYECTO Nombre (s) y Énfasis Profesional: Karem Samoa Díaz Robles TEMA: Análisis Audiovisual – Televisión – Estudios Culturales TIPO DE TRABAJO: Monográfico: ____ Tesis: X Director de trabajo de grado sugerido por Usted: Carlos Durango (Comunicador Social – Periodista Pontificia Universidad Bolivariana) especialista en medios audiovisuales. Título provisional: Una mirada al mundo de LOST Análisis de los elementos de la narrativa audiovisual de la serie que han influenciado culturalmente en la audiencia y su aporte a los shows de su género. - 2 – II. PLANTEAMIENTO DE LA INVESTIGACIÓN 1. PROBLEMA Por medio de esta investigación se pretende desarrollar un análisis de la serie de televisión norteamericana LOST, a partir de una definición de las estructuras narrativas, argumentación, la temática, los personajes, el proceso de producción, los recursos literarios y las referencias culturales que han permitido que esta serie se configure como un hito de la televisión por el impacto que ha tenido en su audiencia. Para llevar a cabo el presente estudio, se hace necesario -

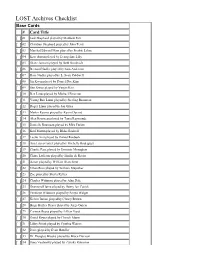

LOST Archives Checklist

LOST Archives Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Jack Shephard played by Matthew Fox [ ] 02 Christian Shephard played by John Terry [ ] 03 Marshal Edward Mars played by Fredric Lehne [ ] 04 Kate Austin played by Evangeline Lilly [ ] 05 Diane Janssen played by Beth Broderick [ ] 06 Bernard Nadler played by Sam Anderson [ ] 07 Rose Nadler played by L. Scott Caldwell [ ] 08 Jin Kwon played by Daniel Dae Kim [ ] 09 Sun Kwon played by Yunjin Kim [ ] 10 Ben Linus played by Michael Emerson [ ] 11 Young Ben Linus played by Sterling Beaumon [ ] 12 Roger Linus played by Jon Gries [ ] 13 Martin Keamy played by Kevin Durand [ ] 14 Alex Rousseau played by Tania Raymonde [ ] 15 Danielle Rousseau played by Mira Furlan [ ] 16 Karl Martin played by Blake Bashoff [ ] 17 Leslie Arzt played by Daniel Roebuck [ ] 18 Ana Lucia Cortez played by Michelle Rodriguez [ ] 19 Charlie Pace played by Dominic Monaghan [ ] 20 Claire Littleton played by Emilie de Ravin [ ] 21 Aaron played by William Blanchette [ ] 22 Ethan Rom played by William Mapother [ ] 23 Zoe played by Sheila Kelley [ ] 24 Charles Widmore played by Alan Dale [ ] 25 Desmond Hume played by Henry Ian Cusick [ ] 26 Penelope Widmore played by Sonya Walger [ ] 27 Kelvin Inman played by Clancy Brown [ ] 28 Hugo Hurley Reyes played by Jorge Garcia [ ] 29 Carmen Reyes played by Lillian Hurst [ ] 30 David Reyes played by Cheech Marin [ ] 31 Libby Smith played by Cynthia Watros [ ] 32 Dave played by Evan Handler [ ] 33 Dr. Douglas Brooks played by Bruce Davison [ ] 34 Ilana Verdansky played by Zuleika