Oral History Interview with Michael Purington, October 17, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Pdf) Download

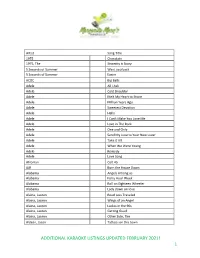

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Big Hits Karaoke Song Book

Big Hits Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 3OH!3 Angus & Julia Stone You're Gonna Love This BHK034-11 And The Boys BHK004-03 3OH!3 & Katy Perry Big Jet Plane BHKSFE02-07 Starstruck BHK001-08 Ariana Grande 3OH!3 & Kesha One Last Time BHK062-10 My First Kiss BHK010-01 Ariana Grande & Iggy Azalea 5 Seconds Of Summer Problem BHK053-02 Amnesia BHK055-06 Ariana Grande & Weeknd She Looks So Perfect BHK051-02 Love Me Harder BHK060-10 ABBA Ariana Grande & Zedd Waterloo BHKP001-04 Break Free BHK055-02 Absent Friends Armin Van Buuren I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHK000-02 This Is What It Feels Like BHK042-06 I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHKSFE01-02 Augie March AC-DC One Crowded Hour BHKSFE02-06 Long Way To The Top BHKP001-05 Avalanche City You Shook Me All Night Long BHPRC001-05 Love, Love, Love BHK018-13 Adam Lambert Avener Ghost Town BHK064-06 Fade Out Lines BHK060-09 If I Had You BHK010-04 Averil Lavinge Whataya Want From Me BHK007-06 Smile BHK018-03 Adele Avicii Hello BHK068-09 Addicted To You BHK049-06 Rolling In The Deep BHK018-07 Days, The BHK058-01 Rumour Has It BHK026-05 Hey Brother BHK047-06 Set Fire To The Rain BHK021-03 Nights, The BHK061-10 Skyfall BHK036-07 Waiting For Love BHK065-06 Someone Like You BHK017-09 Wake Me Up BHK044-02 Turning Tables BHK030-01 Avicii & Nicky Romero Afrojack & Eva Simons I Could Be The One BHK040-10 Take Over Control BHK016-08 Avril Lavigne Afrojack & Spree Wilson Alice (Underground) BHK006-04 Spark, The BHK049-11 Here's To Never Growing Up BHK042-09 -

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

An Advanced Songwriting System for Crafting Songs That People Want to Hear

How to Write Songs That Sell _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ An Advanced Songwriting System for Crafting Songs That People Want to Hear By Anthony Ceseri This is NOT a free e-book! You have been given one copy to keep on your computer. You may print out one copy only for your use. Printing out more than one copy, or distributing it electronically is prohibited by international and U.S.A. copyright laws and treaties, and would subject the purchaser to expensive penalties. It is illegal to copy, distribute, or create derivative works from this book in whole or in part, or to contribute to the copying, distribution, or creating of derivative works of this book. Furthermore, by reading this book you understand that the information contained within this book is a series of opinions and this book should be used for personal entertainment purposes only. None of what’s presented in this book is to be considered legal or personal advice. Published by: Success For Your Songs Visit us on the web at: http://www.SuccessForYourSongs.com Copyright © 2012 by Success For Your Songs All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. How to Write Songs That Sell 3 Table of Contents Introduction 6 The Methods 8 Special Report 9 Module 1: The Big -

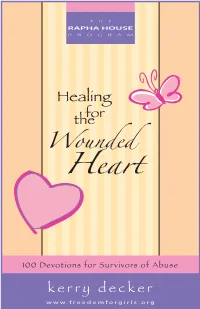

Healing for the Wounded Heart Devotions

100 Devotions for Survivors of Abuse © 2007, 2009, Kerry Decker. All rights reserved. Second Edition Scripture taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. The “NIV” and “New International Version” trademarks are registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by International Bible Society. Use of either trademark requires the permission of International Bible Society. Scripture quotations marked NLT are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright 1996. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Wheaton, Illinois 60189. All rights reserved. Scriptures marked as “(CEV)” are taken from the Contemporary English Version Copyright © 1995 by American Bible Society. Used by permission. Scripture taken from The Message. Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2002. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. The Living Bible. Copyright © 1987 by Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Wheaton, Illinois 60189. All rights reserved. Rapha House Freedom Foundation 6755 Victoria Ave. Riverside, CA 92506 Rapha is the Hebrew word for “healing.” Rapha House in Cambodia provides shelter and care for girls who have survived human trafficking and sexual exploitation. The “Healing for the Wounded Heart” resources, including these devotions, were developed to help these girls with their emotional and spiritual recovery. Many survivors of abuse may not have experienced sexual slavery, but they know what it’s like to be prisoners in dysfunctional families or relationships. And they know what it’s like to be prisoners of their own guilt and shame. All abuse wounds the heart, whether it involves a single incidence or sexual enslavement. -

Harris.Pdf (194.4Kb)

Interview No. SAS4.02.02 Mr. Charles P. Harris Interviewer: Elizabeth Schaaf Location: Baltimore, Maryland Date: April 2, 2002 Edited by: Elizabeth Schaaf Q: Were you born here in Baltimore? Harris: No. I was born at Alexandria, Virginia. Q: And how long were you in Alexandria? Harris: I think I was brought here when I was very, very young. In fact, I can’t remember anything about it that much, you know. Q: So you started your music training here in Baltimore? Harris: Oh yes. Q: Who was your first teacher? Harris: Oh, on the violin my first teacher was Lucien Odendh’al. In fact, I was introduced to him by a teacher up at Douglass High School, the music teacher. Q: Is that Mr. [W. Llewellyn] Wilson? Harris: Mr. Wilson, yes. Way back there. It’s been a good little while. Names evade me a little bit now, but I’m doing pretty well. Q: I think so. Mr. Wilson I think taught everybody who is anybody. Harris: That’s right. In the music field, yes. He was very, very, very good. He started me off, and I worked with him for a year, a year and a half, and he said, I can’t go any further with you. I will have to get a teacher. And so he got in touch with Lucien Odendh’al, and he started to teach me. And he was a very nice man to go to. Q: How did you and the bass get to be a pair? Harris: Well, in high school, in those days, they didn’t have too many musicians that played the bass and what not. -

The Immortal Actuary

THE IMMORTAL ACTUARY by Friday, December 13, 2165 Stacy Kunz hated the subway—a terrible juxtaposition of clean modernism and filthy dilapidation. She hated the LED lights that filled the walls and ceilings of the car, running ads nonstop. The city was quick to fix even a single diode that burned out, but yet slow to fix any of the crumbling infrastructure the cars ran on. At any turn on the centuries-old tracks, it seemed the train could tip over or fall off its rails. And then there were the people themselves—all broken. The world was broken. The modernist look promised a bright future, that everything would be all right, but it was all a lie. What was there to look forward to? Resources were running dry. Everything was becoming more and more expensive. World population was declining, and sicknesses ran rampant. If anything, the past proved that no one could rely on technology. A. I. turned out to be nothing. Forget the singularity; it never happened. Neural networks were cool and could outperform humans on specific tasks, but never delivered what really mattered. They certainly didn’t stop humans from destroying themselves slowly. At least I have a job. Stacy held on to the top rail as she stood inside the crowded car. She was a student actuary at Manhattan Mutual. My job sucks, but I’m surviving. Her only hope was to work her way to the top, else she’d be on the streets. Her thick coat was still zipped up, as she wasn’t yet warmed up from the bitter cold. -

5 0T H International Film Festival Nyon

50 INDUSTRY — VISIONSRÉEL DU 5 0 TH INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL NYON 5 13 APRIL 2019 MAIN PARTNER MEDIA PARTNER INSTITUTIONAL PARTNERS EDITION NO 50 SUMMARY EDITORIAL 5 DAY BY DAY 6 JURY & AWARDS 8 PITCHING DU RÉEL 15 DOCS IN PROGRESS 59 ROUGH CUT LAB 79 SUMMARY PRIX RTS: PERSPECTIVES D’UN DOC 93 SWITZERLAND MEETS... QUÉBEC 103 OPENING SCENES LAB 115 DOC & ART 127 INDUSTRY TALKS 129 IMMERSIVE & INTERACTIVE 132 MEDIA LIBRARY 133 NETWORKING 134 SPECIAL EVENTS 136 MAP & INFORMATION 137 INDUSTRY TEAM 138 SPECIAL THANKS & PARTNERS 139 PROJECTS’ INDEX 142 3 EDITORIAL EMILIE BUJÈS GUDULA MEINZOLT ARTISTIC DIRECTOR HEAD OF INDUSTRY This year, the Festival is celebrating its selected by the Festival’s programmers; 50th edition. Fifty years during which Switzerland meets… Québec, which will Visions du Réel has taken many forms be the occasion for coproduction meet- and directions, has played an essen- ings between producers and institutions EDITORIAL tial role in the festival landscape, both aiming to network; the Opening Scenes in Switzerland and abroad. Revisiting Lab, a programme made for 16 filmmak- and celebrating history on the Festival ers taking part in the Opening Scenes side and with an ofcial selection to be Competition, that allows them to get proud of (no less than 90 films presented better acquainted with the market and as world premieres), the Industry aims to decision makers. bear witness of richness and strength of cinema of the real, not only for today but Several conferences, panels, debates, also in the years to come. work sessions and case studies will take place and are possible thanks to collab- We have selected 27 strong, provoca- orations and partnerships with organisa- tive and diverse projects for our three tions and institutions we are very happy diferent sections: Pitching du Réel, Docs and proud to be working with: On & For in Progress and Rough Cut Lab. -

This Publication Is Dedicated to the Victims of Drunk Driving Crashes. Acknowledgements

Dedication This publication is dedicated to the victims of drunk driving crashes. Acknowledgements This edition of Shattered Lives is being printed by the New York State STOP-DWI Foundation, Inc and is funded by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration with a grant from the New York Depraved Indifference Murder State Governorʼs Traffic Safety Committee. Shattered Lives was originally published by the Broome County STOP-DWI Program in 2003 in collaboration with MADD of Broome County, the Binghamton City School District, the Daniel K Run/Walk and the City of Binghamton Parks Department. Shattered Lives also received generous support from the New York Press Association, David Skyrca Design and Chris Heide, Broome County Department of Information Technology. Shattered Lives was adapted and reprinted in 2005 as a STOP-DWI New York publication reflecting the impact of impaired driving throughout New York State. This second revision in 2007 provides new and updated statewide information and perspectives. The most sincere acknowledgement goes to the courageous people who were wiling to share their painful stories with the reader to prevent future tragedies related to impaired driving. Denise Cashmere, Editor NYS STOP-DWI Foundation Board Each county in New York State has a STOP-DWI Program. These programs are funded by the fines paid by people convicted of impaired driving. To contact a county STOP-DWI Coordinator please visit www.stopdwi.org Introduction In my view, one of the greatest failing in our criminal justice system is its almost single-minded focus on the effect of arrest and prosecution upon the accused, along with its remarkable disregard for the impact of the crime upon the victim and the victim’s friends and family. -

Þtste Sí @Enubßßee

þtste sÍ @enuBßßee HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION NO.I69 By Representative McDonald and Senators Ford, Herron, Tracy, Overbey, Berke, Harper, Crowe A RESOLUTION to honor country music legend Reba McEntire on the occasion of her induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame. WHEREAS, it is fitting that this General Assembly should pay tribute to those gifted musical artists who have reached the very pinnacle of the country music industry; and WHEREAS, Reba McEntire will receive country music's highest honor when she is inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame, an honor most befitting her outstanding career as a superbly talented musician, and WHEREAS, Reba McEntire was born in McAlester, Oklahoma, on March 28, 1955, to Clark Vincent and Jacqueline Smith McEntire; and WHEREAS, the third of four children, Ms. McEntire was raised on her family's 8,000- acre ranch in Chockie, Oklahoma; and WHEREAS, Reba's family traveled frequently to watch her father, who was a World Champion Steer Roper, compete at rodeos, and, during long car rides to visit him, Reba's mother taught the four children how to sing and harmonize; and WHEREAS, during high school, Reba McEntire and two of her siblings were members of the Kiowa High School Cowboy Band and recorded a single, "The Ballad of John McEntire," for Boss Records in 1971; and WHEREAS, the three musical siblings, all of whom grew up to have careers in the music industry, soon formed their own group, The Singing McEntires, and performed frequently at ¡'odeos, clubs, and dance halls; and WHEREAS, upon her graduation from high school, Reba pursued a degree in elementary education and music at Southeastern Oklahoma State University, from which she graduated in 1976; and WHEREAS, on December 10, 1974, Reba McEntire sang the national anthem at the National Rodeo Finals in Oklahoma City and her performance impressed artist Red Steagall so much that he invited her to Nashville to record demos for his music publishing company; and WHEREAS, in 1975, Ms. -

Pdf, 639.57 KB

00:00:00 Music Music “Oh No, Ross and Carrie! Theme Song” by Brian Keith Dalton. A jaunty, upbeat instrumental. 00:00:09 Ross Host Hello! And welcome to Oh No Ross and Carrie—the show where Blocher we don’t just report on fringe science, spirituality, and claims of the paranormal, but we take part ourselves! 00:00:17 Carrie Host Yep! When they make the claims, we show up, so you don’t have Poppy to. I’m Ross Blocher. 00:00:21 Ross Host And I’m… Carrie Poppy. 00:00:23 Carrie Host [Laughs.] Begrudgingly. 00:00:25 Ross Host Well, now I’m gonna get it. 00:00:26 Crosstalk Crosstalk Ross: You know, “You are not Carrie Poppy!” Carrie: From that one little girl. [They laugh.] 00:00:29 Ross Host You know, I think—I think it happened once before camp, and she just resumed right where she left off. 00:00:34 Carrie Host [Laughing.] Ooh, okay. 00:00:36 Ross Host “You are not Carrie Poppy!” 00:00:37 Carrie Host I’ll be honest, this is not the episode for that little girl, anyway. 00:00:40 Ross Host A fair point. Well, actually—that’s a—that’s a good transition. So, we’re—in this episode, we’re very excited. [Carrie agrees.] We’ve got an interview guest that we hinted at that we might have. Isis Aquarian. 00:00:52 Carrie Host Isis was the archivist and historian and a ranking member of the Source family. 00:00:57 Ross Host You may have listened to our episode on the Source family reunion dinner, held at Gratitude in Beverly Hills.