Property Holding, Charitable Purposes and Dissolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trustee Liability Issues –Offshore

TRUSTEE LIABILITY ISSUES –OFFSHORE 11th Annual International Estate Planning Institute March 13th – 4pm, Crowne Plaza, Times Square, New York Vanessa Schrum, Appleby (Bermuda) Limited 1. INTRODUCTION A trustee can be faced with many forms of liability including liabilities to third parties, contractual liabilities, liabilities in tort and liabilities as a titleholder (eg shareholder or owner or land). But perhaps one of the biggest concerns to trustees is potential liability to beneficiaries for breaches of trust. In order to fully appreciate the extent to which trustees may face liability for breaches of trust it is important to understand the duties of trustees. 2. TRUSTEE DUTIES Trustee duties are obligations contained in the trust instrument or imposed by common law or statute, which must be carried out by the trustees. In the Channel Islands (unlike other offshore jurisdictions) generally trustee duties are imposed by statute. Duties and powers prescribed by general law may be modified by the trust instrument, but there are minimum core obligations placed on trustees that cannot be avoided. At their basic a duty to act honestly and in good faith1 and an overriding obligation to preserve and safeguard the trust property. Importantly there is a “duty of care” on the trustees which is a standard that they must meet in every aspect of the performance of the role as trustees. The standard applied to the duty of care differs for lay and professional trustees. Licensed trustees in offshore jurisdictions will also be subject to the Regulations and Codes of Practice issued by the relevant governing authority in that jurisdiction. -

ARMITAGE V. NURSE (1997) the Facts the Settlement Was Made on 11Th. October 1984. It Was the Result of an Application to The

ARMITAGE v. NURSE (1997) The facts The Settlement was made on 11th. October 1984. It was the result of an application to the Court by the trustees of a Marriage Settlement made by Paula’s Grandfather for the variation of the trusts of the settlement under the Variation of Trusts Act 1958. Paula’s Mother was life tenant under the Marriage Settlement and Paula, who was then aged 17, was entitled in remainder. The settled property consisted largely of land which was farmed by a family company called G.W. Nurse & Co. Limited (“the Company”). The Company had farmed the land for many years and until March 1984 it had held a tenancy of the land. Paula’s Mother and Grandmother were the sole directors and shareholders of the Company. Under the terms of the variation the property subject to the trusts of the Marriage Settlement was partitioned between Paula and her Mother. Part of the land together with a sum of £230,000 was transferred to Paula’s Mother absolutely free and discharged from the trusts of the Marriage Settlement. The remainder of the land (“Paula’s land”) together with a sum of £30,000 was allocated to Paula. Since she was under age, her share was directed to be held on the trusts of a settlement prepared for her benefit. So the Settlement came into being. Under the trusts of the Settlement the trustees held the income upon trust to accumulate it until Paula attained 25 with power to pay it to her or to apply it for her benefit. -

An Ordering of the Law of Trusts

This essay was originally Chapter 36 of the third edition of Equity & Trusts, published in 2003. Its purpose was, at the end of that book, to consider the various forms of trust including public interest trusts and unincorporated associations. I am in the course of attempting to put together an article on the ordering of trusts law which will build on these ideas. In time it will appear on this site. AN ORDERING OF THE LAW OF TRUSTS 36.1 INTRODUCTORY The express trust is an equitable institution: one which has hardened over time into something resembling a contract in that the rules for its creation, operation and termination have become concrete.1 This development is due both to its commercial application and its long-standing use as a means of providing for the welfare of rich families in marriage settlements or will trusts. Both of these contexts required certainty in the use of trusts with the result that the general equitable notions have been pushed into the background.2 This chapter suggests that the bright line tendency of much of the law on express trusts towards ever stricter rules means that there is a need for a new division in the categories of the law of trusts. The increasing prominence of pension funds and investment funds based on trusts law principles requires that the existing principles of trusts law be developed to match the regulatory rules applied to such funds. That is aside from the equally difficult developments in the treatment of trusts implied by law.3 This essay attempts to outline some of the ways in which that re- drawing of principles could take effect, once it has re-established the foundations on which trusts law is built in spite of other competing, fashionable notions. -

The Strength of Beneficiaries' Rights Under English Law and the Laws of the Caribbean States

The Strength of Beneficiaries’ Rights Under English Law and the Laws of the Caribbean States The Honourable Mr Justice David Hayton, Judge of the Caribbean Court of Justice A Transcontinental Trust Conference in Geneva Geneva 19 June 2013 Informa Connect gathers millions of professional and commercial customers. Their mission is to give access to extraordinary people and exceptional insight. They provide unique opportunities to learn, establish relationships and do business. They do this through a range of products and services, from digital platforms to live events like the Transcontinental Trust Conference. Remarks By The Honourable Mr Justice David Hayton, Judge of the Caribbean Court of Justice, On the occasion of The Transcontinental Trust Conference in Geneva 19 June 2013 The general background as to beneficiaries’ rights As Millett LJ (as he then was) stated1, “There is an irreducible core of obligations owed by the trustees to the beneficiaries and enforceable by them which is fundamental to the concept of a trust. If the beneficiaries have no rights enforceable against the trustees there are no trusts.” In recent years, however, many settlors have increasingly wished to diminish their beneficiaries’ rights so far as possible. Draftspersons have accommodated these wishes to the extent that they consider possible and many Caribbean States have responded by enacting legislation making clear how far it is possible to diminish beneficiaries’ rights. Indeed, the Cayman Islands went so far as to enact Special Trust Alternative Regime legislation to create special trusts known as STAR trusts where what would normally be the beneficiaries’ rights against the trustees are held only by an enforcer or enforcers appointed pursuant to the terms of the trust or by order of the court. -

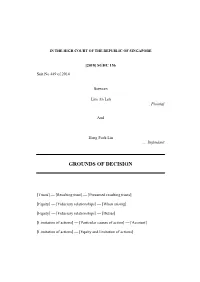

Grounds of Decision

IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2018] SGHC 156 Suit No 449 of 2014 Between Lim Ah Leh … Plaintiff And Heng Fock Lin … Defendant GROUNDS OF DECISION [Trusts] — [Resulting trust] — [Presumed resulting trusts] [Equity] — [Fiduciary relationships] — [When arising] [Equity] — [Fiduciary relationships] — [Duties] [Limitation of actions] — [Particular causes of action] — [Account] [Limitation of actions] — [Equity and limitation of actions] TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................1 SUMMARY OF MY FINDINGS....................................................................2 FACTUAL BACKGROUND ..........................................................................4 THE PARTIES....................................................................................................4 THE PARTIES ENTER INTO AN ARRANGEMENT..................................................5 THE SHANGHAI PROPERTIES ............................................................................5 THE ROCHOR PROPERTY..................................................................................6 THE PLAINTIFF SEEKS AN ACCOUNT.................................................................8 SUMMARY OF PARTIES’ CASES.........................................................................8 ISSUES TO BE DETERMINED............................................................................10 ISSUE 1: RECEIPT OF MONEY ................................................................10 -

Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Know: Part 1 – Background, Cowan V Scargill and MNRPF

The Short-form ‘Best Interests Duty’ – Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Know: Part 1 – Background, Cowan v Scargill and MNRPF David Pollard1 Overview Trustees, company directors and others occupy a ‘fiduciary‘ position towards the relevant trust, company or other principal. There is clearly a need for an explanation to be given to the relevant office holder of what this means – and for judges to describe the relevant duties when looking at claims of breach. How should a trustee board actually exercise a relevant power or discretion? Much of the case law and commentary seeks to encapsulate the essence of the fiduciary duties in a simple phrase: that a trustee owes an overarching duty to ‘act in the best interests of the beneficiaries’. In the UK (where private sector pension schemes are established as express trusts), many pension lawyers play ‘best interests‘ bingo in spotting (and condemning) the use of this phrase. It even creeps into legislation (rather worryingly). But, as this article will seek to demonstrate, this is a very misleading encapsulation of the nature of fiduciary duties. There is a risk that, understandably given its use by judges and sometimes in statutes, trustee boards and directors take the formulation literally. This could easily take them into error. Clearly it does not override the terms of the trust, nor can it be taken literally. This article is split into two parts. Part 1 (‘Background, Cowan v Scargill and MNRPF’) looks at: ● the nature of any best interests duty; ● why does the analysis of the supposed duty matter; ● some examples of a best interests duty in official guidance; ● why the test appears in cases about who is a fiduciary (including looking at the decisions of Millett LJ in Mothew and Armitage v Nurse in this context); ● why a literal duty is both dangerous and imprecise and unworkable; 1 Barrister, Wilberforce Chambers, Lincoln’s Inn. -

Trustee Exculpation—The Law, the Quirks and the Business Sense

Trusts & Trustees, Vol. 20, No. 9, November 2014, pp. 933–942 933 Trustee exculpation—the law, the quirks and the business sense Lawrence Cohen QC and Thomas Seymour Abstract Although the law on this subject has grown out of English case law, its development is now more Trustee exculpation clauses: the law as it stands– closely aligned to offshore trust centres such what duties/liabilities fall outside the standard as Cayman and the Channel Islands which are clause and/or cannot be lawfully excluded: the Downloaded from the engine rooms of modern trust law.1 meaning of ‘wilful default’–how far it extends in practice–the borderline with dishonesty. To what Amongst the consequences of which to be aware extent can the supine trustee rely on a clause which are both the legislative and public policy differences between jurisdictions. One example of a legisla- excepts wilful default? See the Weavering decision. http://tandt.oxfordjournals.org/ Is the ‘wilful default’ standard applied differently tive difference is the Guernsey provision limiting depending on remuneration, professional, and the ability to exculpate in new trusts (see business experience? Points arising on fraud or dis- Spread Trustee discussed below) and the inapplic- honesty. Are wide-form exculpation clauses a bad ability of many of the provisions of the Trustee Act thing? Special considerations affecting professional 2000.2 trustees: the standards applicable, and whether We are principally concerned with profes- such clauses relied on by professional trustees sional trustees who accept their trusteeships in by guest on October 16, 2014 bring the trust industry into disrepute. -

Spread Trustee Company Limited V Sarah Ann Hutcheson & Others

[2011] UKPC 13 Privy Council Appeal No 0007 of 2010 JUDGMENT Spread Trustee Company Limited (Appellant) v Sarah Ann Hutcheson & Others (Respondent) From the Court of Appeal of Guernsey before Lady Hale Lord Mance Lord Kerr Lord Clarke Sir Robin Auld JUDGMENT DELIVERED BY Lord Clarke ON 15 June 2011 Heard on 13 - 14 December 2010 Appellant Respondent Phillip Jones QC Robert Hildyard QC Jonathan Harris John Stephens David Johnston QC Simon Howitt (Instructed by Mayer (Instructed by Harcus Brown International LLP) Sinclair) LORD CLARKE: Introduction 1. This is the judgment of the Board with which Lord Mance and Sir Robin Auld have agreed but to which they have added concurring judgments, with which I agree. 2. On 22 April 1989 there came into force in Guernsey the Trusts (Guernsey) Law 1989 (“the 1989 Law”), which for the first time made statutory provision for Guernsey trusts. It provided by section 34(7): “Nothing in the terms of a trust shall relieve a trustee of liability for a breach of trust arising from his own fraud or wilful misconduct.” Subsection (7) was amended by section 1(f) of the Trusts (Amendment) (Guernsey) Law 1990 (“the Amendment Law”) by the addition of the words “or gross negligence” at the end. The Amendment Law came into force on 19 February 1991. 3. In the proceedings which have given rise to this appeal the respondents (“the beneficiaries”) claim damages for breaches of trust in connection with two settlements made in November 1977. The claims are made against the appellant trustee company (“the trustee”), which is a professional trustee and was appointed as the sole trustee of the settlements on 10 July 1990. -

WILLS and ESTATES Practice Basics 2017

WILLS AND ESTATES Practice Basics 2017 chair Jordan Atin, C.S., TEP Atin Professional Corporation March 27, 2017 *CLE17-0030501-A-PUB* DISCLAIMER: This work appears as part of The Law Society of Upper Canada’s initiatives in Continuing Professional Development (CPD). It provides information and various opinions to help legal professionals maintain and enhance their competence. It does not, however, represent or embody any official position of, or statement by, the Society, except where specifically indicated; nor does it attempt to set forth definitive practice standards or to provide legal advice. Precedents and other material contained herein should be used prudently, as nothing in the work relieves readers of their responsibility to assess the material in light of their own professional experience. No warranty is made with regards to this work. The Society can accept no responsibility for any errors or omissions, and expressly disclaims any such responsibility. © 2017 All Rights Reserved This compilation of collective works is copyrighted by The Law Society of Upper Canada. The individual documents remain the property of the original authors or their assignees. The Law Society of Upper Canada 130 Queen Street West, Toronto, ON M5H 2N6 Phone: 416-947-3315 or 1-800-668-7380 Ext. 3315 Fax: 416-947-3991 E-mail: [email protected] www.lsuc.on.ca Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Wills and Estates Practice Basics 2017 ISBN 978-1-77094-221-0 (Hardcopy) ISBN 978-1-77094-222-7 (PDF) WILLS AND ESTATES Practice Basics 2017 Chair: Jordan Atin, C.S., TEP, Atin Professional Corporation Monday, March 27, 2017 9:00 a.m. -

Rule of Law Symposium 2012

Finance, Property and Business Litigation in a Changing World 25-26 April 2013 Supreme Court Auditorium Organisers: Finance, Property and Business Litigation in a Changing World Plenary Session 2 Trusts and Proprietary Remedies Chairperson Mr Timothy Fancourt QC, Falcon Chambers Speakers The Honourable Judicial Commissioner Vinodh Coomaraswamy, Supreme Court of Singapore Professor Yeo Tiong Min SC, School of Law, Singapore Management University Mr Paul McGrath QC, Essex Court Chambers PROPRIETARY REMEDIES AFTER SINCLAIR V VERSAILLES PAUL McGRATH Q.C. Essex Court Chambers PROPRIETARY REMEDIES IN FRAUD • Litigation about commercial fraud increases in downturn in markets: Madoff, Stanford etc • Availability of proprietary remedies crucial part of armoury of litigator • In seeking to impose restrictions, CA decision in Sinclair v Versailles is disappointing • Also sets English law on a different path Paul McGrath Q.C. Essex Court Chambers FINANCE, PROPERTY AND BUSINESS LITIGATION IN A CHANGING WORLD What did it decide? • Rejected PC in A-G of Hong Kong v Reid in favour of CA in Lister v Stubbs • 䇾…a beneficiary of a fiduciary䇻s duties cannot claim a proprietary interest, but is entitled to an equitable account, in respect of any money or asset acquired by a fiduciary in breach of his duties to the beneficiary, unless the asset or money [A] is or [B] has been beneficially the property of the beneficiary or [C] the trustee acquired the asset or money by taking advantage of an opportunity or right which was properly that of the beneficiary.䇿 per Lord Neuberger MR • Need [A], [B] or [C] to be present for proprietary relief. -

Breach of Trust Discussion Paper

SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION Discussion Paper No 123 Discussion Paper on Breach of Trust September 2003 This Discussion Paper is published for comment and criticism and does not represent the final views of the Scottish Law Commission EDINBURGH: The Stationery Office £xx.xx The Scottish Law Commission was set up by section 2 of the Law Commissions Act 19651 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law of Scotland. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Lord Eassie, Chairman Professor Gerard Maher Professor Kenneth G C Reid Professor Joseph M Thomson. The Secretary of the Commission is Miss Jane L McLeod. Its offices are at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh EH9 1PR. The Commission would be grateful if comments on this discussion paper were submitted by 31 December 2003. Comments may be made on all or any of the matters raised in the paper. All correspondence should be addressed to: Dr David Nichols Scottish Law Commission 140 Causewayside Edinburgh EH9 1PR Tel: 0131 668 2131 Fax: 0131 662 4900 E-mail: [email protected] Online comments at: www.scotlawcom.gov.uk - select "Submit Comments" NOTES 1. Where possible, we would prefer electronic submission of comments, either by e-mail to [email protected] or through the Submit Comments page on our website. We should make it clear that the comments we receive from you may be (i) referred to in any later report on this subject and (ii) made available to any interested party, unless you indicate that all or part of your response is confidential. Such confidentiality will of course be strictly respected. -

TOPIC 2: CREATION of EXPRESS TRUSTS (THE THREE CERTAINTIES) Step 1. Introduction A. Consequences of Creating a Trust Step 2

TOPIC 2: CREATION OF EXPRESS TRUSTS (THE THREE CERTAINTIES) Step 1. Introduction - As [X] is purporting to create a [type] trust, the trust must satisfy [requirements]. o To create a valid express trust, there must be certainty of intention, subject matter and object (Knight), in addition to compliance with statutory formalities and constitution of the trust property. o If the trust fails for some reason, the property will go back to the settlor (trustee would hold on resulting trust for S if trust by transfer) or be disposed of by the rest of the will. a. Consequences of creating a trust - When a trust is validly created, the beneficial interest passes to the beneficiaries. - Therefore, there are IMMEDIATE and BINDING consequences. - These can’t be undone if the settlor changes her mind, or the trustee refuses to act. - Mallott v Wilson established the principle that a trust cannot be revoked, once created, unless a power of revocation exists. - Legal title returns to settlor, who holds ppty subject to the trust. Step 2. Certainty of Intention - RED FLAGS: o Lack of explicit trust language (e.g. no ‘as trustee’, ‘on trust for’, ‘the trust deed’, meaning it is unclear whether it is a trust, a gift, or a gift with a condition) o Precatory language (e.g. ‘on the condition that, hoping that, trusting that, provided that’) o Issues with immediacy (e.g. to commence in 5 years time) - TEST: In order for the clause to be valid, the settlor must have manifested an irrevocable and immediate intention to depart with their beneficial interest in the trust property (Harpur).