Puzzles of State Transformation : the Cases of Armenia and Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country of Origin Information Report Republic of Georgia 25 November

REPUBLIC OF GEORGIA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT Country of Origin Information Service 25 November 2010 GEORGIA 25 NOVEMBER 2010 Contents Preface Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.05 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Post-communist Georgia, 1990-2003.................................................................. 3.02 Political developments, 2003-2007...................................................................... 3.03 Elections of 2008 .................................................................................................. 3.05 Presidential election, January 2008 ................................................................... 3.05 Parliamentary election, May 2008 ...................................................................... 3.06 Armed conflict with Russia, August 2008 .......................................................... 3.09 Developments following the 2008 armed conflict.............................................. 3.10 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS .......................................................................................... -

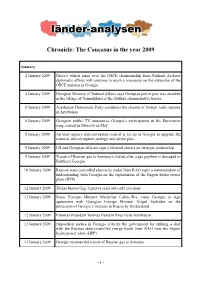

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2009

Chronicle: The Caucasus in the year 2009 January 2 January 2009 Greece, which takes over the OSCE chairmanship from Finland, declares diplomatic efforts will continue to reach a consensus on the extension of the OSCE mission in Georgia 4 January 2009 Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs says Georgian police post was attacked in the village of Ganmukhuri at the Abkhaz administrative border 6 January 2009 Azerbaijan Democratic Party condemns the closure of foreign radio stations in Azerbaijan 6 January 2009 Georgian public TV announces Georgia’s participation in the Eurovision song contest in Moscow in May 8 January 2009 An inter-agency anti-corruption council is set up in Georgia to upgrade the national anti-corruption strategy and action plan 9 January 2009 US and Georgian officials sign a bilateral charter on strategic partnership 9 January 2009 Transit of Russian gas to Armenia is halted after a gas pipeline is damaged in Southern Georgia 10 January 2009 Russian state-controlled electricity trader Inter RAO signs a memorandum of understanding with Georgia on the exploitation of the Enguri hydro power plant (HPP) 12 January 2009 Tbilisi Mayor Gigi Ugulava rules out early elections 12 January 2009 Swiss Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey visits Georgia to sign agreement with Georgian Foreign Minister Grigol Vashadze on the protection of Georgia’s interests in Russia by Switzerland 12 January 2009 Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves visits Azerbaijan 13 January 2009 Opposition parties in Georgia criticize the government for striking -

Adlib Express Watermark

IHS Global Insight Report: Georgia (Country Intelligence) Report printed on 14 January 2009 CONTENTS Country Reports AdlibCopyright ©2008 Express Global Insight Inc. All rights reserved. WatermarkPage 1 of 36 Nature of Risk Rating Summary Political: Risks 2.75 The situation in Georgia is uncertain in the aftermath of the military conflict with Russia, but it is clear that the state will remain functioning, even if the separatist republics claim chunks of its territory (highly unlikely). The economy will pay the price of military damage, although most importantly, crucial elements of the country's infrastructure such as bridges and mountain tunnels have remained intact. President Mikhail Saakashvili, who essentially triggered the hostilities by ordering a Georgian offensive on South Ossetia, will have to fight to retain his seat, which he only won for the second term in January 2008. Given the popular consensus in the face of the Russian offensive, however, Saakashvili may well rely on his charismatic turns to actually elevate and strengthen his domestic position. The government will also remain committed to its economic reform policy, although most of the legislation and regulation is already in place. Economic: Risks 3.50 Georgia is a poor country with weak external financial and trade links outside Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States. The collapse in growth associated with post-Soviet economic management during the early 1990s was heightened in Georgia's case by a brief civil war on its borders. The economy finally began to recover strongly from its collapsed base in the second half of the 1990s. Although Georgian GDP rose steadily in 1995-2006, growth rates have been highly variable, from lows of about 2% to highs of arou nd 11%. -

Russia, NATO, and Black Sea Security for More Information on This Publication, Visit

Russia, NATO, and Black Sea Security Russia, NATO, C O R P O R A T I O N STEPHEN J. FLANAGAN, ANIKA BINNENDIJK, IRINA A. CHINDEA, KATHERINE COSTELLO, GEOFFREY KIRKWOOD, DARA MASSICOT, CLINT REACH Russia, NATO, and Black Sea Security For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA357-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0568-5 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2020 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Cover graphic by Dori Walker, adapted from a photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Weston Jones. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The Black Sea region is a central locus of the competition between Russia and the West for the future of Europe. -

1 Tonoyan.Indd

Rising Armenian–Georgian Tensions and the Possibility of a New Ethnic Conflict in the South Caucasus Artyom Tonoyan Abstract: This article analyzes the recent geopolitical developments in Georgian and Armenian societies and the possibility of a new interstate conflict between the two nations. The article focuses on the role of internal and external political factors, such as the the integration of the Armenian minority in Georgia’s Javakheti region into the political processes and economic projects in that country; unresolved issues concerning the ownership of Armenian churches in Georgia; third-party geopolitical overtures in the region; and the role of new information technologies in social mobilization and political activism. The article finds that despite a centu- ries-old relationship between these two countries, the possibility of new con- flicts in the South Caucasus is, though small, not entirely out-of-the-question. Keywords: Armenia, Georgia, ethnic conflict, South Caucasus he South Caucasus region is in the news again, and not for good reasons. There have T been occasional bursts of headline-grabbing events in the Caucasus since the heyday of Gorbachev-era political reforms and following the collapse of the Soviet Union, many of them having to do with military confrontation between the region’s various ethnoreli- gious inhabitants. Considered the traditional domain of Russian economic, political and military influence, the South Caucasus has generally been absent from Western political and media analysis, but with the recent engagement of the United States and the Euro- Artyom Tonoyan is a doctoral candidate in Religion, Politics & Society in the J.M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies at Baylor University, where he also lectures on nationalism, ethnic conflict, and international human rights. -

081210Cover (Skrivskyddat)

Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst BI-WEEKLY BRIEFING VOL. 10 NO. 24 10 DECEMBER 2008 Searchable Archives with over 1,500 articles at http://www.cacianalyst.org ANALYTICAL ARTICLES: FIELD REPORTS: RUSSIA’S STRATEGIC CHALLENGES IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS: AZERBAIJAN WORLD’S FAMOUS SANTA CLAUSES UNITE IN MOVES CENTER STAGE KYRGYZSTAN Roger N McDermott Erica Marat GOVERNMENT RESHUFFLE IN GEORGIA CHINA’S RECENT ADVANCES Johanna Popjanevski IN CENTRAL ASIA Sébastien Peyrouse TAJIK LABOR MIGRATION AND ITS CONSE- QUENCES FOR WOMEN RECONCILING SHARIA WITH Sergey Medrea REALPOLITIK: THE INTERNATIONAL OUTLOOK OF THE CAUCASUS EMIRATE TURKMENISTAN BOOSTS ITS ROLE IN RE- Kevin Daniel Leahy GIONAL ENERGY COOPERATION Roman Muzalevsky CURRENCY CHANGES IN TURKMENISTAN: NEWS DIGEST ECONOMIC REFORMS ON THE WAY? Rafis Abazov Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst BI-WEEKLY BRIEFING VOL. 10 NO. 24 10 DECEMBER 2008 Contents Analytical Articles RUSSIA’S STRATEGIC CHALLENGES IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS: 3 AZERBAIJAN MOVES CENTER STAGE Roger N McDermott CHINA’S RECENT ADVANCES IN CENTRAL ASIA 6 Sébastien Peyrouse RECONCILING SHARIA WITH REALPOLITIK: 9 THE INTERNATIONAL OUTLOOK OF THE CAUCASUS EMIRATE Kevin Daniel Leahy CURRENCY CHANGES IN TURKMENISTAN: 12 ECONOMIC REFORMS ON THE WAY? Rafis Abazov Field Reports WORLD’S FAMOUS SANTA CLAUSES UNITE IN KYRGYZSTAN 15 Erica Marat GOVERNMENT RESHUFFLE IN GEORGIA 16 Johanna Popjanevski TAJIK LABOR MIGRATION AND ITS CONSEQUENCES FOR WOMEN 18 Sergey Medrea TURKMENISTAN BOOSTS ITS ROLE IN REGIONAL ENERGY COOPERATION 19 Roman Muzalevsky News Digest 21 THE CENTRAL ASIA-CAUCASUS ANALYST Editor: Svante E. Cornell Assistant Editor: Niklas Nilsson Assistant Editor, News Digest: Alima Bissenova Chairman, Editorial Board: S. Frederick Starr The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst is an English-language journal devoted to analysis of the current issues facing Central Asia and the Caucasus. -

Turqay Ceferov. Gürcistan'da Siyasal Sistem: Tarihsel Gelişimi Ve Anayasal

AZERBAYCAN CUMHURİYETİ EĞİTİM BAKANLIĞI AZERBAYCAN DEVLET İKTİSAT ÜNİVERSİTESİ TÜRK DÜNYASI İŞLETME FAKÜLTESİ LİSANS BİTİRME TEZİ Gürcistan’da siyasal sistem: tarihsel gelişimi ve anayasal sistemi Hazırlayan Turqay Ceferov 1417.02002 BAKÜ-2018 AZERBAYCAN DEVLET İKTİSAT ÜNİVERSİTESİ TÜRK DÜNYASI İŞLETME FAKÜLTESİ LİSANS BİTİRME TEZİ GÜRCİSTAN’DA SİYASAL SİSTEM: TARİHSEL GELİŞİMİ VE ANAYASAL SİSTEMİ Danışman Dr. Nazim Ceferov Hazırlayan Turqay CEFEROV 1417.02002 BAKÜ-2018 AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASI TƏHSİL NAZİRLİYİ AZƏRBAYCAN DÖVLƏT İQTİSAD UNİVERSİTETİ Kafedra “İqtisadiyyat və İşlətmə” TƏSDİQ EDİRƏM “___” _________ 2018 BURAXILIŞ İŞİ ÜZRƏ VERİLMİŞ TAPŞIRIQ “Türk Dünyası İşlətmə” fakültəsinin Beynəlxalq Münasibətlər (Uluslararası İlişkiler) ixtisası üzrə təhsil alan tələbəsi Cəfərov Turqay Şahin (adı, soyadı, atasının adı) Diplom işinin rəhbəri Dr. Nazim Cəfərov Kamil (adı, soyadı, atasının adı, elmi adı və dərəcəsi) 1. İşin mövzusu: Gürcistan’da Siyasal Sistem: Tarihsel Gelişimi ve Anayasal Sistemi Azərbaycan Dövlət İqtisad Universiteti tərəfindən təsdiqlənsin “____” __________________ 2018 il No i 2. Tələbənin sona yetirdiyi işin kafedraya təhvil müddəti: 6 ay 3. İşin məzmunu və həcmi (izahı, hesabı və eksperimental hissəsi, yeni təhlilə ehtiyacı olan müəssisələr) Özet, Giriş, Birinci bölüm, İkinci bölüm, Sonuç, Kaynakça 4. Buraxılış işi üçün lazımi materiallar: ANÇABADZE, Giorgi; GAMKRELİZDE, Gela; KİKNADZE, Zurab; SURGULUDZE, Mziya ve ŞVELİDZE, Dimitri (2009), Gürcistan Tarihi, Logos press, Tbilisi. APRASİDZE, David (2011), Electoral System and Process in Georgia: Possible Means for İmprovement, Caucasus İnstitute for Peace, Democracy and Development, Tbilisi. Avrupa Birliği Gürcistan’a vizeyi kaldırdı , http://www.sozcu.com.tr/2017/dunya/avrupa-birligi-gurcistana-vizeyi- kaldirdi-1703466/ , (07.02.2018). BERUÇAŞVİLİ, Niko; DAVİTAŞVİLİ, Zurab ve ELİZBARAŞVİLİ, Nodar (1999), Gürcistan Coğrafyası, İNTELLEKT Yayın Evi, Tbilisi. CNN, Bush: Georgia 's beacon of liberty http://edition.cnn.com/2005/WORLD/europe/05/10/bush.tuesday/ , (26.01.2018). -

Caucasian Review of International Affairs (CRIA) Is a Quarterly Peer-Reviewed Free, Non-Profit and Only-Online Academic Journal Based in Germany

CCCAUCASIAN REVIEW OF IIINTERNATIONAL AAAFFAIRS Vol. 4 (((1(111)))) winter 2020201020 101010 RUSSIA ’S PRAGMATIC REIMPERIALIZATION JANUSZ BUGAJSKI PUZZLES OF STATE TRANSFORMATION : THE CASE OF ARMENIA AND GEORGIA NICOLE GALLINA RUSSIA ’S NATIONAL SECURITY STRATEGY TO 2020: A GREAT POWER IN THE MAKING ? SOPHIA DIMITRAKOPOULOU & ANDREW LIAROPOULOS INTERNATIONAL LANGUAGE RIGHTS NORMS IN THE DISPUTE OVER LATINIZATION REFORM IN THE REPUBLIC OF TATARSTAN DILYARA SULEYMANOVA EUROPEAN FOREIGN POLICY AFTER LISBON : STRENGTHENING THE EU AS AN INTERNATIONAL ACTOR KATERYNA KOEHLER THE FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL : TWENTY YEARS OF REFORM ALEKSANDR SHKOLNIKOV & ANNA NADGRODKIEWICZ KAZAN : THE RELIGIOUSLY UNDIVIDED FRONTIER CITY MATTHEW DERRICK “THE CURRENT TREND OF THE KREMLIN IS TO RATHER FORMALLY DISTANCE ITSELF FROM THE NORTH CAUCASUS ” INTERVIEW WITH DR. EMIL SOULEIMANOV , CHARLES UNIVERSITY , PRAGUE ISSN: 1865-6773 www.cria -online.org EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Nasimi Aghayev, LL.M.Eur. EDITORIAL BOARD: Dr. Tracey German (King’s College Dr. Robin van der Hout (Europa-Institute, London, United Kingdom) University of Saarland, Germany) Dr. Andrew Liaropoulos (Institute for Dr. Jason Strakes (Analyst, Research European and American Studies, Greece) Reachback Center East, USA) Dr. Martin Malek (National Defence Dr. Cory Welt (Georgetown University, Academy, Austria) USA) INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD: Prof. Hüseyin Bagci , Middle East Prof. Werner Münch , former Prime Technical University, Ankara, Turkey Minister of Saxony-Anhalt, former Member of the European Parliament, Germany Prof. Hans-Georg Heinrich, University of Vienna, Austria Prof. Elkhan Nuriyev , Director of the Centre for Strategic Studies under the Prof. Edmund Herzig , Oxford University, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan UK Dr. Roy Allison, London School of Prof. -

Georgia's Democracy “New Wave”

Reform or Retouch? Georgia's New Wave of Democracy 1 www.transparency.gewww.transparency.ge In his address to the Georgian parliament this summer, Joe Biden pointed to fundamental flaws within the Georgian political system and called for action to be taken. The Rose Revolution will only be complete when... issues are debated inside this chamber, not only out on the street; when you fully address key constitutional issues regarding the balance of power between the parliament and executive branch and levelling your electoral playing field; when the media is totally independent and professional... when the courts are free from outside influence and rule of law is firmly established and when the transfer of power occurs through peaceful, constitutional and democratic processes... Vice President Joe Biden, Tbilisi, July 23 2009 In a speech to Parliament before Bidens arrival and in a number of other keynote addresses through- out the last several years President Saakashvili promised to address these very concerns, and vowed a new wave of democratisation. This New Wave promised changes in the structure of government, the inclusion of the opposition, and changes in the electoral system, the media and the judiciary. This report seeks to analyse whether those promised changes are being realized and to what extent they will impact the Georgian political and social landscape. Structure of Government: Broad-reaching constitutional changes are currently being considered that offer an enormous potential for long-term strengthening of checks and balances in Georgia. However, because of the overwhelming majority of the ruling party in the current parliament, where it holds 2/3 of seats, any efforts to increase parliaments powers are unlikely to have impact until the next presiden- tial and parliamentary elections. -

“Building a Modern State in 21St Century - Georgia”

3 September Wednesday (Day 3) Close Session only for CDDRL Fellows and Faculty 9:30-12:30 Close Session only for CDDRL Fellows and Faculty towards Building an Alumni Network and Community 12:30-14:00 Lunch 14:00-15:30 Sight visit to the Public Service Hall 16:00-17:30 Lecture at Free University Agenda of the Conference: 20:00 Graduation Dinner at Funicular Restaurant hosted by the Bank of Georgia University. By invitation only. ON Leadership Forum “Building a Modern State in 21st Century - Georgia” September 1-3, 2014 September 1-3, 2014 Conference Participants: Mr.Giorgi Kadagidze, President of the National Bank of Georgia; Mr. Venue: Courtyard Marriott Hotel Kakha Bendukidze, Chairman, Board of Trustees, Free University and Agricultural Working Language: English with a simultaneous interpretation into Georgian University of Georgia; Mr. Lasha Dolidze, Board Member, Economic Policy Research Center (EPRC); Mr. George Chirakadze, Head of Supervisory Board, President of Business Association of Georgia. 1 September Monday (Day 1) 20:00 Gala Reception hosted by H.E. Giorgi Margvelashvili, President of Georgia at the 08:30-09:00 Welcome Coffee and Registration Presidential Palace. By invitation only. 09:00-09:30 Opening Remarks by H.E. Giorgi Margvelashvili, President of Georgia; H.E. Irakli Garibashvili, Prime Minister of Georgia; Mr. David Usupashvili, Chairman of the 2 September Tuesday (Day 2) Parliament of Georgia; H.E. Richard Norland, Ambassador of the U.S. to Georgia; Ms. Keti Khutsishvili, Director of the Open Society Georgia Foundation; Stanford 09:00-10:45 Panel Discussion I – Regional confl ict and instability: The Situation in Ukraine / Faculty. -

The Covid-19 Pandemic Its Impact on Georgia and Beyond to Our Readers

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC ITS IMPACT ON GEORGIA AND BEYOND TO OUR READERS We are pleased to present you the first issue of The Journal of Frontline Democracy, published by Economic Policy Research Center and Fukuyama Democracy Frontline Center. We decided to create this journal to offer our readers a selection of the best articles written within the framework of the research and analysis work of our centers. In this journal, you will have the opportunity to get acquainted with the views and opinions of Georgian as well as foreign experts and decision- makers on both global and regional issues. THE PUBLICATION WAS MADE POSSIBLE BY THE BLACK SEA TRUST, A PROJECT OF THE GERMAN MARSHALL FUND OF THE UNITED STATES. OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN THIS PUBLICATION DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT THOSE OF THE BLACK SEA TRUST OR ITS PARTNERS. © ECONOMIC POLICY RESEARCH CENTER 2020 CONTENT 5 Introduction VIEWS FROM GEORGIA: 11 The Pandemic Outlook: Economic Impact and Implications for Georgia – Irina Guruli 33 Lessons from Pandemic for Social Protection System of Georgia – Andrew Urushadaze 43 Post-Pandemic: Rethinking and Rearranging the Critical Infrastructure in Georgia – Batu Kutelia 55 The Post-Pandemic Characteristics of Global Order: A Georgian Perspective – Grigol Mgaloblishvili 65 Contemporary security environment and future trends in the times of pandemics – Shota Gvineria FROM MOSCOW: 81 Russia’s Corona Challenge: Domestic and Foreign Policy Implications; Russia-Georgia Relationship in the Pandemic Context – Lilia Shevtsova 95 Russia as The Global Challenge – Lilia Shevtsova FROM THE STATES: 117 The Pandemic, Democracy and the United States: Implications for the Black Sea Region – David J.Kramer 125 Transatlantic Relations: From Bad To Worse To What Next? – David J.Kramer INTRODUCTION As this publication goes to print, there are more than 43 million cases of COVID-19 in the world, including more than 1.1 million deaths, according to the World Health Organization. -

The Russian Factor in Turkey's Georgian Policy After the Russian- Georgian War (August 2008)

International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM) ||Volume||08||Issue||04||Pages||EM-2020-1738-1747||2020|| Website: www.ijsrm.in ISSN (e): 2321-3418 DOI: 10.18535/ijsrm/v8i04.em06 The Russian Factor in Turkey's Georgian Policy after the Russian- Georgian War (August 2008) Murad Asadov Azerbaijan, Baku State University, International Relations and Economic Faculty, Ph. D, Abstract Formation of new states in the South Caucasus and Central Asia after the collapse of the Soviet Union raised to have relations with the Turkic peoples of Central Asia first in the history of the Republic for Turkey. Foreign policy the Caucasus continues to evolve in its foreign policy strategy. A force associated with this well-intentioned policy, which is adjacent to the Laki region, is always offered. Whenever Turkey wants to enter the Caucasus, it will not be adversely affected by other countries. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, Russia's influence in the region was weak. The nickname was temporary. At the beginning of the 21st century, Vladimir Putin received a well-developed document with the credibility of Putin. Turkey’s north-east neighbour Georgia is not a very big country, it has a particular importance of the geostrategic position not only in the Caucasus region but also in Turkey. Especially, the location of Georgia in the centre of the transport and trade routes to the Caucasus and Central Asia increases its geostrategic status more. The main positive turning point in the development of Georgia-Turkey relations happened with the realization of oil and natural gas pipelines to run Caspian oil through Tbilisi to Turkey and from there to the West.