1 Tonoyan.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Orontids of Armenia by Cyril Toumanoff

The Orontids of Armenia by Cyril Toumanoff This study appears as part III of Toumanoff's Studies in Christian Caucasian History (Georgetown, 1963), pp. 277-354. An earlier version appeared in the journal Le Muséon 72(1959), pp. 1-36 and 73(1960), pp. 73-106. The Orontids of Armenia Bibliography, pp. 501-523 Maps appear as an attachment to the present document. This material is presented solely for non-commercial educational/research purposes. I 1. The genesis of the Armenian nation has been examined in an earlier Study.1 Its nucleus, succeeding to the role of the Yannic nucleus ot Urartu, was the 'proto-Armenian,T Hayasa-Phrygian, people-state,2 which at first oc- cupied only a small section of the former Urartian, or subsequent Armenian, territory. And it was, precisely, of the expansion of this people-state over that territory, and of its blending with the remaining Urartians and other proto- Caucasians that the Armenian nation was born. That expansion proceeded from the earliest proto-Armenian settlement in the basin of the Arsanias (East- ern Euphrates) up the Euphrates, to the valley of the upper Tigris, and espe- cially to that of the Araxes, which is the central Armenian plain.3 This expand- ing proto-Armenian nucleus formed a separate satrapy in the Iranian empire, while the rest of the inhabitants of the Armenian Plateau, both the remaining Urartians and other proto-Caucasians, were included in several other satrapies.* Between Herodotus's day and the year 401, when the Ten Thousand passed through it, the land of the proto-Armenians had become so enlarged as to form, in addition to the Satrapy of Armenia, also the trans-Euphratensian vice-Sa- trapy of West Armenia.5 This division subsisted in the Hellenistic phase, as that between Greater Armenia and Lesser Armenia. -

The Image of the Cumans in Medieval Chronicles

Caroline Gurevich THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES MA Thesis in Medieval Studies CEU eTD Collection Central European University Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis -

Freedom of Religion Or Belief in Georgia 2010-2019

FREEDOM OF RELIGION OR BELIEF IN GEORGIA Report 2010-2019 FREEDOM OF RELIGION OR BELIEF IN GEORGIA REPORT 2010-2019 Tolerance and Diversity Institute (TDI) 2020 The report is prepared by Tolerance and Diversity Institute (TDI) within the framework of East-West Management Institute’s (EWMI) "Promoting Rule of Law in Georgia" (PROLoG) project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The report is published with the support from the Open Society Georgia Foundation (OSGF). The content is the sole responsibility of the Tolerance and Diversity Institute (TDI) and does not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), United States Government, East-West Management Institute (EWMI) or Open Society Georgia Foundation (OSGF). Authors: Mariam Gavtadze, Eka Chitanava, Anzor Khatiashvili, Mariam Jikia, Shota Tutberidze, Gvantsa Lomaia Project director: Mariam Gavtadze Translators: Natia Nadiradze, Tamar Kvaratskhelia Design: Tornike Lortkipanidze Cover: shutterstock It is prohibited to reprint, copy or distribute the material for commercial purposes without written consent of the Tolerance and Diversity Institute (TDI). Tolerance and Diversity Institute (TDI), 2020 Web: www.tdi.ge CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 Methodology ..........................................................................................................................................................10 -

Acceptance and Rejection of Foreign Influence in the Church Architecture of Eastern Georgia

The Churches of Mtskheta: Acceptance and Rejection of Foreign Influence in the Church Architecture of Eastern Georgia Samantha Johnson Senior Art History Thesis December 14, 2017 The small town of Mtskheta, located near Tbilisi, the capital of the Republic of Georgia, is the seat of the Georgian Orthodox Church and is the heart of Christianity in the country. This town, one of the oldest in the nation, was once the capital and has been a key player throughout Georgia’s tumultuous history, witnessing not only the nation’s conversion to Christianity, but also the devastation of foreign invasions. It also contains three churches that are national symbols and represent the two major waves of church building in the seventh and eleventh centuries. Georgia is, above all, a Christian nation and religion is central to its national identity. This paper examines the interaction between incoming foreign cultures and deeply-rooted local traditions that have shaped art and architecture in Transcaucasia.1 Nestled among the Caucasus Mountains, between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, present-day Georgia contains fewer than four million people and has its own unique alphabet and language as well as a long, complex history. In fact, historians cannot agree on how Georgia got its English exonym, because in the native tongue, kartulad, the country is called Sakartvelo, or “land of the karvelians.”2 They know that the name “Sakartvelo” first appeared in texts around 800 AD as another name for the eastern kingdom of Kartli in Transcaucasia. It then evolved to signify the unified eastern and western kingdoms in 1008.3 Most scholars agree that the name “Georgia” did not stem from the nation’s patron saint, George, as is commonly thought, but actually comes 1 This research addresses the multitude of influences that have contributed to the development of Georgia’s ecclesiastical architecture. -

Armenian Monuments Awareness Project

Armenian Monuments Awareness Project Armenian Monuments Awareness Project he Armenian Monuments Awareness Proj- ect fulfills a dream shared by a 12-person team that includes 10 local Armenians who make up our Non Governmental Organi- zation. Simply: We want to make the Ar- T menia we’ve come to love accessible to visitors and Armenian locals alike. Until AMAP began making installations of its infor- Monuments mation panels, there remained little on-site mate- rial at monuments. Limited information was typi- Awareness cally poorly displayed and most often inaccessible to visitors who spoke neither Russian nor Armenian. Bagratashen Project Over the past two years AMAP has been steadily Akhtala and aggressively upgrading the visitor experience Haghpat for local visitors as well as the growing thousands Sanahin Odzun of foreign tourists. Guests to Armenia’s popular his- Kobair toric and cultural destinations can now find large and artistically designed panels with significant information in five languages (Armenian, Russian, Gyumri Fioletovo Aghavnavank English, French, Italian). Information is also avail- Goshavank able in another six languages on laminated hand- Dilijan outs. Further, AMAP has put up color-coded direc- Sevanavank tional road signs directing drivers to the sites. Lchashen Norashen In 2009 we have produced more than 380 sources Noratuz of information, including panels, directional signs Amberd and placards at more than 40 locations nation- wide. Our Green Monuments campaign has plant- Lichk Gegard ed more than 400 trees and -

Puzzles of State Transformation : the Cases of Armenia and Georgia

PUZZLES OF STATE TRANSFORMATION : THE CASES OF ARMENIA AND GEORGIA Nicole Gallina ∗∗∗ Abstract The problems of weak state structures, including state territoriality, in the South Caucasus has highly influenced political developments and the building of a democratic state. This paper explains the difficulty of recovering statehood in the cases of Armenia and Georgia, both in the context of post–Soviet state transformation and post–conflict state-rebuilding. It argues that recovering statehood in the South Caucasus meant at once maintaining the status quo within the state structures and managing the highly volatile political and ethnic relations (culminating in armed conflict). In the cases of conflict, elite management impeded conflict solution. In this context, this paper finds that elite power slowed the construction of a democratic and effective state. In particular, elite fragmentation has led to serious impediments for state development and the consolidation of territoriality. In sum, elite-led state development and conflict management hindered the successful consolidation of state territoriality. Keywords: Armenia, Georgia, state-building, frozen conflicts, elite fragmentation Introduction In the South Caucasus, questions of state reform and state territoriality have dominated the post- Soviet situation. In particular, the insufficient consolidation of state territoriality has had a great impact on the overall state capacities, often characterized by large military budgets and low social spending. Instable territoriality and separatist tendencies led to military conflicts in both Armenia and Georgia – most recently in Georgia in August 2008. The example of Georgia has clearly shown the importance of territorial questions in post-Soviet political development. The first hot conflict phase in the early 1990s resulted in the heavy destruction of infrastructure and in the degradation of living conditions . -

Buildings in Their Patrons' Hands? the Multiform Function of Small Size

Transkulturelle Perspektiven 3/2014 - 1 - و Maria Cristina Carile Buildings in their patrons’ hands? The multiform function of small size models between Byzantium and Transcaucasia The representation of the church model in the hands order to understand the value of these models after of the church's patron or founder finds its roots in the the twelfth century – following the chronological frame arts of Late Antiquity. Since the sixth century, this mo- of this volume – it is important to determine their im- tif adorned church apses, as an image of offering to portance in Caucasian visual culture, first tracing the Christ or the Virgin. 1 Later, it became a strong iconic evolution of the donation image. This will help us to image conveying the role of the patron/founder in the evaluate the meaning of architectural models in the construction and his devotion, which was embodied changed historical context of the Transcaucasian in the model as well as in the building itself. As such, principalities between the late twelfth and the thir- the theme had particular fortune in medieval Rome teenth centuries, when architectural models on and spread to the East as far as the Caucasus. After church walls were enriched with new meanings. the Latin conquest of Constantinople during the fourth crusade (1204 AD), the motif was widely adopted in The first appearance of the motif in the Transcaucasi- the Balkans and in the territories in close contact with an area probably dates back to the sixth century. This Byzantium. 2 This paper will focus on church models is testified by a now-lost sculpted relief with the im- as a motif, reflecting on their spread and role in the age of a woman holding a church model, which may decoration of the external façades of the churches in have decorated the outer walls of the cathedral com- the Caucasus and, specifically, in the area of Trans- plex at Agarak (region of Ayrarat), formed by a fifth- or caucasia. -

Country of Origin Information Report Republic of Georgia 25 November

REPUBLIC OF GEORGIA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT Country of Origin Information Service 25 November 2010 GEORGIA 25 NOVEMBER 2010 Contents Preface Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.05 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Post-communist Georgia, 1990-2003.................................................................. 3.02 Political developments, 2003-2007...................................................................... 3.03 Elections of 2008 .................................................................................................. 3.05 Presidential election, January 2008 ................................................................... 3.05 Parliamentary election, May 2008 ...................................................................... 3.06 Armed conflict with Russia, August 2008 .......................................................... 3.09 Developments following the 2008 armed conflict.............................................. 3.10 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS .......................................................................................... -

Armenian Tourist Attraction

Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... rediscover armenia guide armenia > tourism > rediscover armenia guide about cilicia | feedback | chat | © REDISCOVERING ARMENIA An Archaeological/Touristic Gazetteer and Map Set for the Historical Monuments of Armenia Brady Kiesling July 1999 Yerevan This document is for the benefit of all persons interested in Armenia; no restriction is placed on duplication for personal or professional use. The author would appreciate acknowledgment of the source of any substantial quotations from this work. 1 von 71 13.01.2009 23:05 Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... REDISCOVERING ARMENIA Author’s Preface Sources and Methods Armenian Terms Useful for Getting Lost With Note on Monasteries (Vank) Bibliography EXPLORING ARAGATSOTN MARZ South from Ashtarak (Maps A, D) The South Slopes of Aragats (Map A) Climbing Mt. Aragats (Map A) North and West Around Aragats (Maps A, B) West/South from Talin (Map B) North from Ashtarak (Map A) EXPLORING ARARAT MARZ West of Yerevan (Maps C, D) South from Yerevan (Map C) To Ancient Dvin (Map C) Khor Virap and Artaxiasata (Map C Vedi and Eastward (Map C, inset) East from Yeraskh (Map C inset) St. Karapet Monastery* (Map C inset) EXPLORING ARMAVIR MARZ Echmiatsin and Environs (Map D) The Northeast Corner (Map D) Metsamor and Environs (Map D) Sardarapat and Ancient Armavir (Map D) Southwestern Armavir (advance permission -

Armenians in the Making of Modern Georgia

Armenians in the Making of Modern Georgia Timothy K. Blauvelt & Christofer Berglund While sharing a common ethnic heritage and national legacy, and an ambiguous status in relation to the Georgian state and ethnic majority, the Armenians in Georgia comprise not one, but several distinct communities with divergent outlooks, concerns, and degrees of assimilation. There are the urbanised Armenians of the capital city, Tbilisi (earlier called Tiflis), as well as the more agricultural circle of Armenians residing in the Javakheti region in southwestern Georgia.1 Notwithstanding their differences, these communities have both helped shape modern Armenian political and cultural identity, and still represent an intrinsic part of the societal fabric in Georgia. The Beginnings The ancient kingdoms of Greater Armenia encompassed parts of modern Georgia, and left an imprint on the area as far back as history has been recorded. Moreover, after the collapse of the independent Armenian kingdoms and principalities in the 4th century AD, some of their subjects migrated north to the Georgian kingdoms seeking save haven. Armenians and Georgians in the Caucasus existed in a boundary space between the Roman-Byzantine and Iranian cultures and, while borrowing from both spheres, struggled to preserve their autonomy. The Georgian regal Bagratids shared common origins with the Armenian Bagratuni dynasty. And as part of his campaign to forge a unified Georgian kingdom in the late 11th and early 12th centuries, the Georgian King David the Builder encouraged Armenian merchants to settle in Georgian towns. They primarily settled in Tiflis, once it was conquered from the Arabs, and in the town of Gori, which had been established specifically for Armenian settlers (Lordkipanidze 1974: 37). -

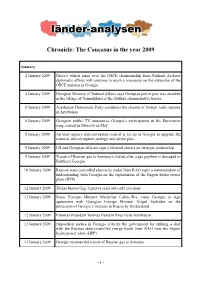

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2009

Chronicle: The Caucasus in the year 2009 January 2 January 2009 Greece, which takes over the OSCE chairmanship from Finland, declares diplomatic efforts will continue to reach a consensus on the extension of the OSCE mission in Georgia 4 January 2009 Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs says Georgian police post was attacked in the village of Ganmukhuri at the Abkhaz administrative border 6 January 2009 Azerbaijan Democratic Party condemns the closure of foreign radio stations in Azerbaijan 6 January 2009 Georgian public TV announces Georgia’s participation in the Eurovision song contest in Moscow in May 8 January 2009 An inter-agency anti-corruption council is set up in Georgia to upgrade the national anti-corruption strategy and action plan 9 January 2009 US and Georgian officials sign a bilateral charter on strategic partnership 9 January 2009 Transit of Russian gas to Armenia is halted after a gas pipeline is damaged in Southern Georgia 10 January 2009 Russian state-controlled electricity trader Inter RAO signs a memorandum of understanding with Georgia on the exploitation of the Enguri hydro power plant (HPP) 12 January 2009 Tbilisi Mayor Gigi Ugulava rules out early elections 12 January 2009 Swiss Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey visits Georgia to sign agreement with Georgian Foreign Minister Grigol Vashadze on the protection of Georgia’s interests in Russia by Switzerland 12 January 2009 Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves visits Azerbaijan 13 January 2009 Opposition parties in Georgia criticize the government for striking -

Adlib Express Watermark

IHS Global Insight Report: Georgia (Country Intelligence) Report printed on 14 January 2009 CONTENTS Country Reports AdlibCopyright ©2008 Express Global Insight Inc. All rights reserved. WatermarkPage 1 of 36 Nature of Risk Rating Summary Political: Risks 2.75 The situation in Georgia is uncertain in the aftermath of the military conflict with Russia, but it is clear that the state will remain functioning, even if the separatist republics claim chunks of its territory (highly unlikely). The economy will pay the price of military damage, although most importantly, crucial elements of the country's infrastructure such as bridges and mountain tunnels have remained intact. President Mikhail Saakashvili, who essentially triggered the hostilities by ordering a Georgian offensive on South Ossetia, will have to fight to retain his seat, which he only won for the second term in January 2008. Given the popular consensus in the face of the Russian offensive, however, Saakashvili may well rely on his charismatic turns to actually elevate and strengthen his domestic position. The government will also remain committed to its economic reform policy, although most of the legislation and regulation is already in place. Economic: Risks 3.50 Georgia is a poor country with weak external financial and trade links outside Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States. The collapse in growth associated with post-Soviet economic management during the early 1990s was heightened in Georgia's case by a brief civil war on its borders. The economy finally began to recover strongly from its collapsed base in the second half of the 1990s. Although Georgian GDP rose steadily in 1995-2006, growth rates have been highly variable, from lows of about 2% to highs of arou nd 11%.