William Lescaze Reconsidered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One: Introduction: Impressionism, Consumer Culture and Modern Women

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84080-4 - Modern Women and Parisian Consumer Culture in Impressionist Painting Ruth E. Iskin Excerpt More information one: introduction: impressionism, consumer culture and modern women < Shall I tell you what was the finest thing I ever produced since I first began to work, and the one which I recall with the greatest pleasure? It’s quite a story . I produced a perfect work of art. I took the dishes, the plates, the pans, and the jars, and arranged the different colors; I devised a wonderful picture of still life, with subtle scales of tints leading up to brilliant flashes of color. It was something barbaric and superb, suggesting a paunch amid a halo of glory; but there was such a cutting sarcastic touch about it all that people crowded to the window, alarmed by the fierce flare of the shop front. Emile Zola, Le ventre de Paris, 18731 Z ola’s 1873 novel, Le ventre de Paris, published a year before the first Impres- sionist exhibition, includes an avant-garde artist, Claude Lantier, who was based on Manet and the Impressionists. In this novel about Les Halles, Zola portrays his artist as obsessed with the market and keenly aware of its role in the epochal changes the capital is undergoing.2 Yet Claude remains a passionate observer who cannot depict the market in his paintings. In his own judgment, his best “work” was a startling “still life,” in which he turned the glittering goods in the window of a recently opened charcuterie from an appetizing display of pork products into a sarcastic critique. -

THE LEADING CHESS MOIITHLY News

THE LEADING CHESS MOIITHLY News. Pictures. Games. Problems • Learn winning technique from Rubinstein's brilliant games you CAN GET more practical information on how to play winning chess by study Rubinstein (Black) Won ing the games of the great RUBINSTEIN than in Four Crushing Moves! you could obtain from a dozen theoretical text-books. 1 ... RxKtl! By playing over the selections in "Rubin stein's Chess Masterpieces," you will see for 2 PxQ yourself how this great strategist developed R.Q7!! his game with accuracy and precision, over 3 QxR came his world-renowned opponents with BxBch crushing blows in the middle-game or with superb, polished technique in the end-game, 4 Q-Kt2 There is no beller or more pleasant way of R·HS!! inproving your knowledge of chess. You will 5 Resigns enjoy these games for their entertainment value alone. You will learn how to apply the This startling combination from Ru underlying principles of Rubinstein's winning binstein's "Immortal Game" reveals technique to your own games. Complete and his great genius and shows how the thorough annotations explain the intricacies Grandmaster used "blitz-krieg" tac of Rubinstein's play, help you to understand tics when given the opportunity. the motives and objectives. CREATIVE GENIUS REVEALED IN GAMES See Page 23 of this new book con Rubinstein has added more to chess theory taining 100 of Rubinstein's brilliant. and technique than any other master in the instructive games. Just published. past 30 years! His creative genius is revealed Get your copy NOW. in this book. -

Benjamin Tallmadge Trail Guide.P65

Suffolk County Council, BSA The Benjamin Tallmadge Historic Trail Suffolk County Council, BSA Brookhaven, New York The starting point of this Trail is the Town of Brookhaven parking lot at Cedar Beach just off Harbor Beach Road in Mount Sinai, NY. Hikers can be safely dropped off at this loca- tion. 90% of this trail follows Town roadways which closely approximate the original route that Benjamin Tallmadge and his contingent of Light Dragoons took from Mount Sinai to the Manor of St. George in Mastic. Extreme CAUTION needs to be observed on certain heavily traveled roads. Some Town roads have little or no shoulders at all. Most roads do not have sidewalks. Scouts should hike in a single line fashion facing the oncoming traffic. They should be dressed in their Field Uniforms or brightly colored Class “B” shirt. This Trail should only be hiked in the daytime hours. Since this 21 mile long Trail is designed to be hiked over a two day period, certain pre- arrangements must be made. The overnight camping stay can be done at Cathedral Pines County Park in Middle Island. Applications must be obtained and submitted to the Suffolk County Parks Department. On Day 2, the trail veers off Smith Road in Shirley onto a ser- vice access road inside the Wertheim National Wildlife Refuge for about a mile before returning to the neighborhood roads. As a courtesy, the Wertheim Refuge would like a letter three weeks in advance informing them that you will be hiking on their property. There are no water sources along this hike so make sure you pack enough. -

Exhibition of Architecture for the Modern School

^B-MUSEUM OF MODERN ART lt WEST 53RD STREET, NEW YORK ,, FPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 TgLE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MUSEUM OP MODERN ART OPENS EXHIBITION OF ARCHITECTURE FOR THE MODERN SCHOOL The latest development in elementary school architecture embodies the intimate and personal qualities of the little red school- house of our forefathers. The importance of modern architecture in meeting a child1s psychological as well as physical needs will be shown in an exhibition Modern Architecture for the Modern School which opens to the public Wednesday, September 16, at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street. The exhibition has been designed by Elizabeth Mock for the Department of Circulating Exhibitions, which will send it on a tour of schools, colleges and museums throughout the country after it closes at the Museum of Modern Art on October 18, The exhibition consists of 40 enlargements of the best modern schools for the elementary grades, a scale model, and 30 panels with drawings, photographs and explanatory labels which contrast the old and the new methods of elementary education and show the contribution modern architecture can make to modern education. Examples of good modern design are shown not only in schoolhouses of the United States but in those of Brazil, England, France, Sweden and Switzerland. A few non-elementary schools are shown, which present different problems but similar principles of design. Solutions of the problems of school-building brought about by priorities in materials and stoppage of non-essential construction are also considered. Mrs. Mock, designer of the exhibition, comments on its purpose as follows: "Educators today are very much concernod with child psychology, but they often forget that the child's sense of unity and security, his appreciation of honesty and beauty, are affected by his school surroundings as well as by his school activities. -

Neighborhood Preservation Center

Landmarks Preservation Commission January 27, 1976, Number 1 LP-0898 LESCAZE HOUSE, 211 East 43th Street Borough of Manhattan. Built 1933-34; archite~t William Lescaze. ' Landl'.lark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1322, Lot 107. On September 23, 1975, the Landmarks Preservation Cor.~ission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Land~ark of the Lescnze House and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.2). 1be hearing was continued to November 25, 1975 (Item No. 1). B'oth hearings had been duly ~vertised in accordance with the provisior.s of law. A total of three Wltnesses spoke in favor of designation at the two hearings. ~~ry Lescaze, owner of the house, has given her approval of the designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Lescaze House of 1933-34, desi~ed by William Lescaze for his own use as a co~bined residence and architectural office, is an ernbodiDent of the theory and practice of one of the most influential exponents of modern archi tecture in the United States. His go~l -- the creation of an architecture expressive of the spirit and life of the 20th century and of each client•s' indi vidual roquirements -- is fully r~aiizcd in this house by an ha~onious - design of deceptive siEplicity, dete~ined by a rational, functional plan, and developed through the use of the newest available technology, materials and Ee~ods of co~struction. The sudden appearance on East 48th Street of this startlingly "raodern" facade of 1934, set between deteriorating brownstones of the post-Civil War period, had a drama. -

Fall 04 Newsletter

-MORR ST O O W P Post-Morrow Foundation FOUNDATION, INC. EWSLETTER volume 14, number 1 Summer 2010 Board of Directors N and Officers Bruce T. Wallace AMLET REES President, Director H T Thomas B. Williams Vice-President The Brookhaven Village Association (BVA) has been planting new trees around Director Thomas Ludlam the Hamlet for the last several years. You may have seen them. They usually have Secretary, Director two cedar stakes on each side to keep them upright and sometimes have a green Ginny Everitt water irrigation bag around them so they may be well-watered over time. More Treasurer, Director than 128 trees have been planted so far in the Hamlet. Norman Nelson Director Dorothy Hubert Jones You can see a map of where they have been planted and the types of trees at: Trustee Emerita http://www.brookhavenvillageassociation.org/treemap/BVATreeMap.htm. Faith McCutcheon Trustee Emerita About 100 years ago, James Post planted Norway maple trees along Beaver Dam Staff Florence Pope Road and other streets in the Hamlet. Recently they have been dying out due Administrative Assistant to age. Because of this loss of street trees , the BVA has undertaken to replace Kenny Budny them in order to keep the lovely, shaded ambience of our roadways. Facilities Manager Today , Norway maple is a frequent History of Post-Morrow invader of urban and suburban The Post-Morrow Foundation, Inc. is located in the Hamlet of forests. Its extreme shade tolerance, Brookhaven, Suffolk County, New York. Its principal office is at 16 Bay especially when young, has allowed it Road, Brookhaven, NY 11719. -

Evolution of a Modern American Architecture: Adding to Square Shadows

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1-1-2007 Evolution of A Modern American Architecture: Adding to Square Shadows Fon Shion Wang University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Wang, Fon Shion, "Evolution of A Modern American Architecture: Adding to Square Shadows" (2007). Theses (Historic Preservation). 93. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/93 A Thesis in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2007. Advisor: David G. De Long This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/93 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evolution of A Modern American Architecture: Adding to Square Shadows Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments A Thesis in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2007. Advisor: David G. De Long This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/93 EVOLUTION OF A MODERN AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE: ADDING TO SQUARE SHADOWS Fon Shion Wang A THESIS In Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2007 ________________________ ______________________________ Advisor Reader David G. De Long John Milner Professor Emeritus of Architecture Adjunct Professor of Architecture _______________________________ Program Chair Frank G. -

Anchin, ANAGPIC 2013, 1 Dina Anchin Straus Center For

Anchin, ANAGPIC 2013, 1 Dina Anchin Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies/Harvard Art Museums Refining Style: Technical Investigation of an Early Work by Georges Pierre Seurat in the Maurice Wertheim Collection Anchin, ANAGPIC 2013, 2 Table of Contents 1. Abstract 2. Introduction 3. Georges Pierre Seurat 3.1. Artistic Development and The Early Works 3.2. Aesthetic and Scientific Influences 4. Vase of Flowers 4.1. Technical Investigation of the Painted Structure 4.2. Materials Identification: Palette 4.3. Technique/Materials in later works 5. Applying Theories to Vase of Flowers 6. Conclusion 7. References and Bibliography 8. List of Images 9. Appendices Appendix 1. Letter to Félix Fénéon: Paris, June 20, 1890 Appendix 2. Images of Cross-sections Appendix 3. Condition Report, Treatment Proposal and Treatment Report for Vase of Flowers Anchin, ANAGPIC 2013, 3 1. Abstract: Throughout his artistic career, Georges Seurat devoted himself to the current color and aesthetic theories of his time. Early on, he began applying these theories to canvas, fine-tuning both his technique and selection of materials, culminating in his mature style, pointillism, around 1886, exemplified by A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. This study investigates an early work by Seurat, Vase of Flowers, c. 1878 - c. 1879, in the Harvard Art Museum’s Wertheim Collection, painted around the time he quit the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1879. A number of recent studies (Kirby, Jo. et al. 2003; Herbert and Harris 2004) have characterized Seurat’s later style, technique, and material choices; there is, however, a dearth of material about his earliest works. -

High Cross House Modernist Icon

High Cross House Modernist Icon High Cross House is one of the most loved buildings on the Dartington estate. It is the pre-eminent 1930s Modernist building in Devon and one of the earliest International Style buildings in the UK. Sadly, despite a successful renovation in the 1990s, High Cross House has fallen into disrepair and we are keen to put this right. Its architect, William Lescaze, was ahead of his time and construction technology had not yet evolved sufficiently to make the building work properly. Huge progress in this field means that the building can now be restored in a way that fully realises Lescaze’s vision. We are committed to raising the funds necessary to bring it back to life so that it is once again buzzing with people and ideas. Once restored, it will become the home of our new Learning Lab, a trans-disciplinary think-tank for new ideas about the future of education and other important issues. As High Cross House was originally built to be a house (and in fact is one of the most intact pieces of domestic architecture from this period in the UK), our aim is to also ensure that it will be accessible to visit and/or stay in at certain times. As you walk around this exhibition, you will learn more about the history of the building, its radical and controversial nature, and understand more about the next phase of its life. How High Cross House Came To Be When William B Curry was offered the role of headmaster at the newly created Dartington Hall School, he suggested William Lescaze as the architect Oak Lane Country Day School William Curry designed by William Lescaze Headmaster of Dartington Hall School to design the new headmaster’s residence. -

Llfornia STAGES U.S. TITLE MATCH Everyone I

• "",., ",." rh ~ ' ~ LlFORNIA STAGES U.S. TITLE MATCH Everyone i. in good humor ill> the t en·game match for the United St a t es Champion ship get a under way in Los Ange les. Challenger Herman Steiner ( left) I, determined to prov ide iI worthy follow-up t o h is recent international t riumphs ; Champion Arn old S, Denker (rig ht) exu des qu iet confidence; Cyril Towbin (st anding ), pre,ident of the sponsor ing Los Feliz Chess Club, is announcing the moves t o the audience; and C randmaster Reuben Fine (center) seems t o f i nd the ro le of referee mOlt congenial. • • RUNAWAY BESTSELLER! Now In ItS 48th Thousand by IRVING CHERNEV and KENNETH HARKNESS HIS new Picture Guide to Chess has shattered all sales records for chess books! Published in 1945, more than 27,000 copies were T sol d during the first year! Another 20,000 copies have been printed to supply the ever-increasing demand. A total of 47,600 copies are now in print! Why has this book sold in such quantities? Why have so many people bought An Invitatfon to Chess after looking through all the other chess primers in bookstores? Here are some of the reasons: • An Invitation to Chess teaches the • Part Two gives the reader· athOl rules and basic principles of ch ess by ough g rounding in thtl basic principles III a new, visual·aid method of instruction, chess: The Relative Values of t he Ches!· originated by the editors of CHESS RE· men; The Princlple of Superior Force : VIEW. -

3 Fischer Vs. Bent Larsen

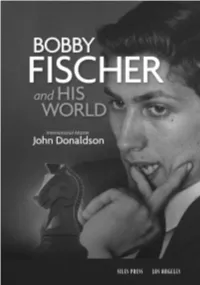

Copyright © 2020 by John Donaldson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. First Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Donaldson, John (William John), 1958- author. Title: Bobby Fischer and his world / by John Donaldson. Description: First Edition. | Los Angeles : Siles Press, 2020. Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020031501 ISBN 9781890085193 (Trade Paperback) ISBN 9781890085544 (eBook) Subjects: LCSH: Fischer, Bobby, 1943-2008. | Chess players--United States--Biography. | Chess players--Anecdotes. | Chess--Collections of games. | Chess--Middle games. | Chess--Anecdotes. | Chess--History. Classification: LCC GV1439.F5 D66 2020 | DDC 794.1092 [B]--dc23 Cover Design and Artwork by Wade Lageose a division of Silman-James Press, Inc. www.silmanjamespress.com [email protected] CONTENTS Acknowledgments xv Introduction xvii A Note to the Reader xx Part One – Beginner to U.S. Junior Champion 1 1. Growing Up in Brooklyn 3 2. First Tournaments 10 U.S. Amateur Championship (1955) 10 U.S. Junior Open (1955) 13 3. Ron Gross, The Man Who Knew Bobby Fischer 33 4. Correspondence Player 43 5. Cache of Gems (The Targ Donation) 47 6. “The year 1956 turned out to be a big one for me in chess.” 51 7. “Let’s schusse!” 57 8. “Bobby Fischer rang my doorbell.” 71 9. 1956 Tournaments 81 U.S. Amateur Championship (1956) 81 U.S. Junior (1956) 87 U.S Open (1956) 88 Third Lessing J. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

I \\ V / / UNITEDSTATHS DEPARTMENT OFTHt INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC Sun Terrace AND/OR COMMON Frederick V. Field House LOCATION STREET& NUMBER Stub Hollow Re«:d _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT New Hartford VICINITY OF 6th, Toby Moffett STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Connecticut 09 Litchfield 005 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE .DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE _MUSEUM -BUILDING(S) 2LPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK .STRUCTURE —BOTH 3L.WORKIN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL -XPRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS -OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Michael M. Taylor STREETS. NUMBER 12 Stonemill Road CITY. TOWN STATE Storrs VICINITY OF Connecticut LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Town Clerk STREET & NUMBER Town Hall CITY. TOWN STATE New Hartford Connecticut REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE 'Subdivision Plan Map of Land Owned by Michael M. Taylor" DATE April, 1977 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY *_LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Office of the Town Clerk, Town Hall CITY. TOW STATE New Hartford Connecticut CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE_____ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Sun Terrace is situated on 7.86 acres of a wooded hilltop about four miles to the south and west of the center of New Hartford, Connecticut It is an International Style country house forming an isolated promitory with exposure to the east, west, and additionally, a fine view to the south.