Henry Morgenthau's Voice in History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“100 Percent American”: Henry Morgenthau Jr. and American Jewry, 1934-1945 Lucy

Reconciling American Jewishness with the “100 Percent American”: Henry Morgenthau Jr. and American Jewry, 1934-1945 Lucy Hammet Senior Research Capstone History 480, Senior Research Seminar Dr. Vivien Dietz Hammet 2 Reflecting on his childhood, his family, and his religion, Henry Morgenthau III, son and namesake of FDR’s Secretary of the Treasury, wrote in 1991 of his Jewish heritage, calling it “a kind of birth defect that could not be eradicated but with proper treatment could be overcome, if not in this generation then probably in the next. The cure was achieved through the vigorous lifelong exercise of one’s Americanism.”1 He goes on to recount a childhood memory that took place in the early 1920s in New York City when a fellow playmate asked about his religion. Later, he confronted his parents with the question, “What’s my religion?” In response, Morgenthau III was taught the following: “If anyone ever asks you that again, just tell them you’re an American.”2 And that is what he did for much of his life. Had he asked his father, Henry Morgenthau Jr., this same question twenty years later, the answer would likely have been very different. By the end of World War II, Morgenthau Jr. was a leader in the American Jewish establishment, chairman of the United Jewish Appeal, and an aggressive actor in the struggle to save the remaining Jews of Europe. His son understood this change as having “sprung from something hidden deep within his conscience.”3 In reality, Morgenthau was one of many American Jews who underwent a turbulent change in experience of Jewishness in the 1930s and 1940s. -

One: Introduction: Impressionism, Consumer Culture and Modern Women

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84080-4 - Modern Women and Parisian Consumer Culture in Impressionist Painting Ruth E. Iskin Excerpt More information one: introduction: impressionism, consumer culture and modern women < Shall I tell you what was the finest thing I ever produced since I first began to work, and the one which I recall with the greatest pleasure? It’s quite a story . I produced a perfect work of art. I took the dishes, the plates, the pans, and the jars, and arranged the different colors; I devised a wonderful picture of still life, with subtle scales of tints leading up to brilliant flashes of color. It was something barbaric and superb, suggesting a paunch amid a halo of glory; but there was such a cutting sarcastic touch about it all that people crowded to the window, alarmed by the fierce flare of the shop front. Emile Zola, Le ventre de Paris, 18731 Z ola’s 1873 novel, Le ventre de Paris, published a year before the first Impres- sionist exhibition, includes an avant-garde artist, Claude Lantier, who was based on Manet and the Impressionists. In this novel about Les Halles, Zola portrays his artist as obsessed with the market and keenly aware of its role in the epochal changes the capital is undergoing.2 Yet Claude remains a passionate observer who cannot depict the market in his paintings. In his own judgment, his best “work” was a startling “still life,” in which he turned the glittering goods in the window of a recently opened charcuterie from an appetizing display of pork products into a sarcastic critique. -

William Lescaze Reconsidered

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Spring 1984 William Lescaze Reconsidered William H. Jordy Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Architectural History and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Jordy, William H. "William Lescaze Reconsidered." William Lescaze and the Rise of Modern Design in America. Spec. issue of The Courier 19.1 (1984): 81-104. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES CO URI ER THE RISE OF MODERN DESIGN IN AMERICA A BRIEF SURVEY OF THE SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY A R. CHI TEe T U R A L H 0 L 0 I N GS VOLUME XIX 1 SPRING 1 984 Contents Foreword by Chester Soling, Chairman of the Syracuse University 5 Library Associates WILLIAM LESCAZE AND THE RISE OF MODERN DESIGN IN AMERICA Preface by Dennis P. Doordan, Assistant Professor of Architecture, 7 Tulane University, and Guest Editor William Lescaze and the Machine Age by Arthur ]. Pulos, Pulos Design Associates, Inc., and 9 Professor Emeritus, Syracuse University William Lescaze and Hart Crane: A Bridge Between Architecture and Poetry by Lindsay Stamm Shapiro, Parsons School of Design 25 The "Modern" Skyscraper, 1931 by Carol Willis, Parsons School of Design 29 William Lescaze and CBS: A Case Study in Corporate Modernism by Dennis P. Doordan, Assistant Professor of Architecture, 43 Tulane University European Modernism in an American Commercial Context by Robert Bruce Dean, Assistant Professor of Architecture, 57 Syracuse University William Lescaze Symposium Panel Discussion Respondents: Stuart Cohen, University of Illinois 67 Werner Seligmann, Syracuse University Robert A. -

THE LEADING CHESS MOIITHLY News

THE LEADING CHESS MOIITHLY News. Pictures. Games. Problems • Learn winning technique from Rubinstein's brilliant games you CAN GET more practical information on how to play winning chess by study Rubinstein (Black) Won ing the games of the great RUBINSTEIN than in Four Crushing Moves! you could obtain from a dozen theoretical text-books. 1 ... RxKtl! By playing over the selections in "Rubin stein's Chess Masterpieces," you will see for 2 PxQ yourself how this great strategist developed R.Q7!! his game with accuracy and precision, over 3 QxR came his world-renowned opponents with BxBch crushing blows in the middle-game or with superb, polished technique in the end-game, 4 Q-Kt2 There is no beller or more pleasant way of R·HS!! inproving your knowledge of chess. You will 5 Resigns enjoy these games for their entertainment value alone. You will learn how to apply the This startling combination from Ru underlying principles of Rubinstein's winning binstein's "Immortal Game" reveals technique to your own games. Complete and his great genius and shows how the thorough annotations explain the intricacies Grandmaster used "blitz-krieg" tac of Rubinstein's play, help you to understand tics when given the opportunity. the motives and objectives. CREATIVE GENIUS REVEALED IN GAMES See Page 23 of this new book con Rubinstein has added more to chess theory taining 100 of Rubinstein's brilliant. and technique than any other master in the instructive games. Just published. past 30 years! His creative genius is revealed Get your copy NOW. in this book. -

Benjamin Tallmadge Trail Guide.P65

Suffolk County Council, BSA The Benjamin Tallmadge Historic Trail Suffolk County Council, BSA Brookhaven, New York The starting point of this Trail is the Town of Brookhaven parking lot at Cedar Beach just off Harbor Beach Road in Mount Sinai, NY. Hikers can be safely dropped off at this loca- tion. 90% of this trail follows Town roadways which closely approximate the original route that Benjamin Tallmadge and his contingent of Light Dragoons took from Mount Sinai to the Manor of St. George in Mastic. Extreme CAUTION needs to be observed on certain heavily traveled roads. Some Town roads have little or no shoulders at all. Most roads do not have sidewalks. Scouts should hike in a single line fashion facing the oncoming traffic. They should be dressed in their Field Uniforms or brightly colored Class “B” shirt. This Trail should only be hiked in the daytime hours. Since this 21 mile long Trail is designed to be hiked over a two day period, certain pre- arrangements must be made. The overnight camping stay can be done at Cathedral Pines County Park in Middle Island. Applications must be obtained and submitted to the Suffolk County Parks Department. On Day 2, the trail veers off Smith Road in Shirley onto a ser- vice access road inside the Wertheim National Wildlife Refuge for about a mile before returning to the neighborhood roads. As a courtesy, the Wertheim Refuge would like a letter three weeks in advance informing them that you will be hiking on their property. There are no water sources along this hike so make sure you pack enough. -

Fall 04 Newsletter

-MORR ST O O W P Post-Morrow Foundation FOUNDATION, INC. EWSLETTER volume 14, number 1 Summer 2010 Board of Directors N and Officers Bruce T. Wallace AMLET REES President, Director H T Thomas B. Williams Vice-President The Brookhaven Village Association (BVA) has been planting new trees around Director Thomas Ludlam the Hamlet for the last several years. You may have seen them. They usually have Secretary, Director two cedar stakes on each side to keep them upright and sometimes have a green Ginny Everitt water irrigation bag around them so they may be well-watered over time. More Treasurer, Director than 128 trees have been planted so far in the Hamlet. Norman Nelson Director Dorothy Hubert Jones You can see a map of where they have been planted and the types of trees at: Trustee Emerita http://www.brookhavenvillageassociation.org/treemap/BVATreeMap.htm. Faith McCutcheon Trustee Emerita About 100 years ago, James Post planted Norway maple trees along Beaver Dam Staff Florence Pope Road and other streets in the Hamlet. Recently they have been dying out due Administrative Assistant to age. Because of this loss of street trees , the BVA has undertaken to replace Kenny Budny them in order to keep the lovely, shaded ambience of our roadways. Facilities Manager Today , Norway maple is a frequent History of Post-Morrow invader of urban and suburban The Post-Morrow Foundation, Inc. is located in the Hamlet of forests. Its extreme shade tolerance, Brookhaven, Suffolk County, New York. Its principal office is at 16 Bay especially when young, has allowed it Road, Brookhaven, NY 11719. -

Anchin, ANAGPIC 2013, 1 Dina Anchin Straus Center For

Anchin, ANAGPIC 2013, 1 Dina Anchin Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies/Harvard Art Museums Refining Style: Technical Investigation of an Early Work by Georges Pierre Seurat in the Maurice Wertheim Collection Anchin, ANAGPIC 2013, 2 Table of Contents 1. Abstract 2. Introduction 3. Georges Pierre Seurat 3.1. Artistic Development and The Early Works 3.2. Aesthetic and Scientific Influences 4. Vase of Flowers 4.1. Technical Investigation of the Painted Structure 4.2. Materials Identification: Palette 4.3. Technique/Materials in later works 5. Applying Theories to Vase of Flowers 6. Conclusion 7. References and Bibliography 8. List of Images 9. Appendices Appendix 1. Letter to Félix Fénéon: Paris, June 20, 1890 Appendix 2. Images of Cross-sections Appendix 3. Condition Report, Treatment Proposal and Treatment Report for Vase of Flowers Anchin, ANAGPIC 2013, 3 1. Abstract: Throughout his artistic career, Georges Seurat devoted himself to the current color and aesthetic theories of his time. Early on, he began applying these theories to canvas, fine-tuning both his technique and selection of materials, culminating in his mature style, pointillism, around 1886, exemplified by A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. This study investigates an early work by Seurat, Vase of Flowers, c. 1878 - c. 1879, in the Harvard Art Museum’s Wertheim Collection, painted around the time he quit the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1879. A number of recent studies (Kirby, Jo. et al. 2003; Herbert and Harris 2004) have characterized Seurat’s later style, technique, and material choices; there is, however, a dearth of material about his earliest works. -

Vol. 77, No. 27.Qxd

T EMPLE E MANU-EL Bulletin Volume 77, Number 27 March 4, 2005 U PCOMING E VENTS Tuesday, March 15 6:30 p.m. Thursday, March 10 6 p.m. MEET American Jewish Reform Sisterhoods of Manhattan: Sacred Space: A Journey of Spirit The Memory of the All are welcome to this viewing of A Journey of THE AUTHOR Lower East Side Spirit, Ann Coppel’s award-winning documentary about Debbie Friedman and her contribution to asia R. Diner is the Paul and Jewish music. Dinner and wine will be served H Sylvia Steinberg Professor of before the film. Both Ms. Coppel and American Jewish History at New York Ms. Friedman will join us afterward for questions. University, with a joint appointment in the This event will be held at Congregation department of history and the Skirball Rodeph Sholom, 7 West 83rd Street. Cost is Department of $25 per person. RSVP to the Women’s Auxiliary Hebrew and Judaic at (212) 744-1400, ext. 235. Studies. She also is director of the Friday, March 11 6:30 p.m. Goldstein Goren Seventh Grade Sabbath Dinner Center for American Seventh grade Religious School students are Jewish History. invited to dinner in the private dining room of In 1998, Ms. Diner Palm Too, 840 Second Avenue. RSVP to was invited to Rabbi Posner at (212) 744-1400, ext. 202. become a fellow in the American Academy for S ABBATH S ERVICES Jewish Research. She was welcomed as a member of the Society of American Historians in 2004. Friday evening, March 11 A specialist in immigration and ethnic Main Sanctuary history, Ms. -

Llfornia STAGES U.S. TITLE MATCH Everyone I

• "",., ",." rh ~ ' ~ LlFORNIA STAGES U.S. TITLE MATCH Everyone i. in good humor ill> the t en·game match for the United St a t es Champion ship get a under way in Los Ange les. Challenger Herman Steiner ( left) I, determined to prov ide iI worthy follow-up t o h is recent international t riumphs ; Champion Arn old S, Denker (rig ht) exu des qu iet confidence; Cyril Towbin (st anding ), pre,ident of the sponsor ing Los Feliz Chess Club, is announcing the moves t o the audience; and C randmaster Reuben Fine (center) seems t o f i nd the ro le of referee mOlt congenial. • • RUNAWAY BESTSELLER! Now In ItS 48th Thousand by IRVING CHERNEV and KENNETH HARKNESS HIS new Picture Guide to Chess has shattered all sales records for chess books! Published in 1945, more than 27,000 copies were T sol d during the first year! Another 20,000 copies have been printed to supply the ever-increasing demand. A total of 47,600 copies are now in print! Why has this book sold in such quantities? Why have so many people bought An Invitatfon to Chess after looking through all the other chess primers in bookstores? Here are some of the reasons: • An Invitation to Chess teaches the • Part Two gives the reader· athOl rules and basic principles of ch ess by ough g rounding in thtl basic principles III a new, visual·aid method of instruction, chess: The Relative Values of t he Ches!· originated by the editors of CHESS RE· men; The Princlple of Superior Force : VIEW. -

3 Fischer Vs. Bent Larsen

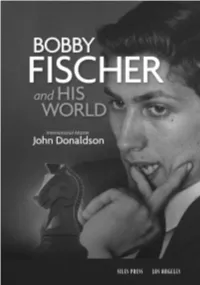

Copyright © 2020 by John Donaldson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. First Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Donaldson, John (William John), 1958- author. Title: Bobby Fischer and his world / by John Donaldson. Description: First Edition. | Los Angeles : Siles Press, 2020. Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020031501 ISBN 9781890085193 (Trade Paperback) ISBN 9781890085544 (eBook) Subjects: LCSH: Fischer, Bobby, 1943-2008. | Chess players--United States--Biography. | Chess players--Anecdotes. | Chess--Collections of games. | Chess--Middle games. | Chess--Anecdotes. | Chess--History. Classification: LCC GV1439.F5 D66 2020 | DDC 794.1092 [B]--dc23 Cover Design and Artwork by Wade Lageose a division of Silman-James Press, Inc. www.silmanjamespress.com [email protected] CONTENTS Acknowledgments xv Introduction xvii A Note to the Reader xx Part One – Beginner to U.S. Junior Champion 1 1. Growing Up in Brooklyn 3 2. First Tournaments 10 U.S. Amateur Championship (1955) 10 U.S. Junior Open (1955) 13 3. Ron Gross, The Man Who Knew Bobby Fischer 33 4. Correspondence Player 43 5. Cache of Gems (The Targ Donation) 47 6. “The year 1956 turned out to be a big one for me in chess.” 51 7. “Let’s schusse!” 57 8. “Bobby Fischer rang my doorbell.” 71 9. 1956 Tournaments 81 U.S. Amateur Championship (1956) 81 U.S. Junior (1956) 87 U.S Open (1956) 88 Third Lessing J. -

China Lobby. ------1

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2003 In Support of “New China”: Origins of the China Lobby, 1937-1941 Tae Jin Park Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Asian History Commons Recommended Citation Park, Tae Jin, "In Support of “New China”: Origins of the China Lobby, 1937-1941" (2003). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7369. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7369 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In Support of “New China”: Origins of the China Lobby, 1937-1941. Tae Jin Park Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Jack L. Hammersmith, Ph.D., Chair Elizabeth A. Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. A. Michal McMahon, Ph.D. Jason C. Parker, Ph.D. Hong N. Kim, Ph.D. -

Press Release Harvard Art Museums' Renovated and Expanded Facility

Press Release Harvard Art Museums’ Renovated and Expanded Facility Opens November 16, 2014 New home provides greater access to the collections, among the nation’s largest and most renowned, for students, faculty, scholars, and the public The Harvard Art Museums (October 25, 2014). Photo: Peter Vanderwarker. Cambridge, MA March 11, 2014 (updated November 5, 2014) The Harvard Art Museums—comprising the Fogg Museum, the Busch-Reisinger Museum, and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum—open their new Renzo Piano Building Workshop–designed facility to the public on November 16, 2014. The renovation and expansion of the museums’ landmark building at 32 Quincy Street in Cambridge brings the three museums and their collections together under one roof for the first time, inviting students, faculty, scholars, and the public into one of the world’s great institutions for arts scholarship and research. In the Harvard Art Museums’ new home, visitors are able to explore new research connected to the objects on display and the ideas they generate in the galleries; gain a glimpse of leading conservators at work; and in the unique Art Study Center, have hands-on experiences with a wide range of objects from the collections. “We are eagerly anticipating the opening of the new Harvard Art Museums facility,” said Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust. “Renzo Piano has designed a building that is as beautiful as the works of art it will house and as thoughtful as the people who will work and learn within it. It will expand the ways in which we use art and art-making as part of the curriculum, and it will invite our neighbors and visitors to enjoy some of the university’s unparalleled treasures.” The design for the new Harvard Art Museums creates new resources for study, teaching, exhibition, and conservation.