La Fornarina Does Not Have Breast Cancer M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raphael Sanzio

1 Born in Urbino in 1483, Raffaello is a 2 He started his career in Perugia under the guide of “Il Perugino” , but 3 He decided to move to Florence, preeminent artist of the Italian Renaissance. His as early as 18 it was acknowledged that he possessed a unique talent fascinated by the work of Leonardo and father, Giovanni Santi (Sanzio meaning Santi’s), and he was commissioned works all around Umbria. Michelangelo. was a famous artist and ran a flourishing workshop in Urbino, one of the most important artistic towns at that time; it was there that Raffaello approached art. At the age of eight the young artist lost his mother. His father passed away a few years later. 5 His workshop gathered both young apprentices and famous artists who worked with him on several projects at the same time. 4 At 25 Raphael triumphed with the frescoes in the Pope’s rooms, creating one of the most renowned works of art of the Renaissance: The school of Athens 6 Not only was Raphel an artist, but he (1509-1511). was also an architect: since 1514 he worked on the project of St Peter’s Basilica Raphael Sanzio 7 Raphael’s strength is in the emotional 8 Among his most important work: The Marriage of the charge the artist endows the characters’ Virgin (1504), in Saint France’s Church in Città di Raphael died at the early age of 37. His 9 faces, which manages to communicate Castello, The Resurrection of Christ (1501) kept at the body is the Pantheon, in Rome Museu de Arte in San Pao, Brazil, the Madonna of the their feelings Goldfinch (1507) at the Uffizi Museum in Florence, La fornarina (1518-1519) e The trasfiguration , his last work. -

RAFFAELLO SANZIO Una Mostra Impossibile

RAFFAELLO SANZIO Una Mostra Impossibile «... non fu superato in nulla, e sembra radunare in sé tutte le buone qualità degli antichi». Così si esprime, a proposito di Raffaello Sanzio, G.P. Bellori – tra i più convinti ammiratori dell’artista nel ’600 –, un giudizio indicativo dell’incontrastata preminenza ormai riconosciuta al classicismo raffaellesco. Nato a Urbino (1483) da Giovanni Santi, Raffaello entra nella bottega di Pietro Perugino in anni imprecisati. L’intera produzione d’esordio è all’insegna di quell’incontro: basti osservare i frammenti della Pala di San Nicola da Tolentino (Città di Castello, 1500) o dell’Incoronazione di Maria (Città del Vaticano, Pinacoteca Vaticana, 1503). Due cartoni accreditano, ad avvio del ’500, il coinvolgimento nella decorazione della Libreria Piccolomini (Duomo di Siena). Lo Sposalizio della Vergine (Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera, 1504), per San Francesco a Città di Castello (Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera), segna un decisivo passo di avanzamento verso la definizione dello stile maturo del Sanzio. Il soggiorno a Firenze (1504-08) innesca un’accelerazione a tale processo, favorita dalla conoscenza dei tra- guardi di Leonardo e Michelangelo: lo attestano la serie di Madonne con il Bambino, i ritratti e le pale d’altare. Rimonta al 1508 il trasferimento a Roma, dove Raffaello è ingaggiato da Giulio II per adornarne l’appartamento nei Palazzi Vaticani. Nella prima Stanza (Segnatura) l’urbinate opera in autonomia, mentre nella seconda (Eliodoro) e, ancor più, nella terza (Incendio di Borgo) è affiancato da collaboratori, assoluti responsabili dell’ultima (Costantino). Il linguaggio raffaellesco, inglobando ora sollecitazioni da Michelangelo e dal mondo veneto, assume accenti rilevantissimi, grazie anche allo studio dell’arte antica. -

Case 8 2013/14: Portrait of a Lady Called Barbara Salutati , By

Case 8 2013/14: Portrait of a Lady called Barbara Salutati, by Domenico Puligo Expert adviser’s statement Reviewing Committee Secretary’s note: Please note that any illustrations referred to have not been reproduced on the Arts Council England website Executive Summary 1. Brief Description of Item Domenico degli Ubaldini, called ‘Il Puligo’ (Florence 1492-1527 Florence) Portrait of a Lady, probably Barbara Rafficani Salutati, half-length, seated at a table, holding an open book of music, with a volume inscribed PETRARCHA Oil on panel, c. 1523-5 100 x 80.5 cms Inscribed in gold on the cornice of the architecture: MELIORA. LATENT Inscribed in gold on the edge of the table: TV.DEA.TV.PRESE[N]S.NOSTRO.SVCCVRRE LABORI A half-length portrait of a woman wearing a red dress with gold trim, and tied with a bow at her waist. Around her neck are a string of pearls and a gold necklace. She wears a black and gold headdress with a brooch at the centre. Seated behind a green table she holds open a book of music. A book at her right hand is closed. The book at her left hand is open; it has text in Italian and on its edge: ‘Petrarcha’. Behind her is greenish-grey classical architecture. The upper left corner of the painting depicts a hilly landscape at sunset. A tower and battlements can be seen behind the tree on which stand tiny figures. Beneath an arch is another small figure. From this arch a bridge spans a stream. 2. Context Provenance Giovanni Battista Deti, Florence, by the second half of 16th century (according to Borghini, Il Ripsoso (1584), if this is the painting first mentioned by Vasari) ; Purchased by George Nassau Cowper, 3rd Earl Cowper (1738-1789) by 1779 for his Florentine palazzo (picture list no. -

Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar | Epicurean Traveler

Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar | Epicurean Traveler https://epicurean-traveler.com/rome-celebrates-raphael-superstar/?... U a Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar by Lucy Gordan | Travel | 0 comments Self-portrait of Raphael with an unknown friend This year the world is celebrating the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death with exhibitions in London at both the National Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum, in Paris at the Louvre, and in Washington D.C. at the National Gallery. However, the mega-show, to end all shows, is “Raffaello 1520-1483” which opened on March 5th and is on until June 2 in Rome, where Raphael lived the last 12 years of his short life. Since January 7th over 70,000 advance tickets sales from all over the world have been sold and so far there have been no cancellations in spite of coronavirus. Not only is Rome an appropriate location, but so are the Quirinal’s scuderie or stables, as the Quirinal was the summer palace of the popes, then the home of Italy’s Royal family and now of its President. On display are 240 works-of-art; 120 of them (including the Tapestry of The Sacrifice of Lystra based on his cartoons and his letter to Medici-born Pope Leo X (reign 1513-21) about the importance of preserving Rome’s antiquities) are by Raphael himself. Twenty- 1 of 9 3/6/20, 3:54 PM Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar | Epicurean Traveler https://epicurean-traveler.com/rome-celebrates-raphael-superstar/?... seven of these are paintings, the others mostly drawings. Never before have so many works by Raphael been displayed in a single exhibition. -

FORNARINA. May 2012

Amado Rafael (sobre Rafael y la Fornarina) Un drama en dos actos ©©© Aurora MATEOS 1 AMADO RAFAEL __________________________________________________ La obra ha sido legalmente registrada. Queda prohibida, salvo excepción prevista en la ley, cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación publica, espectáculo y transformación de esta obra sin contar con la autorización de Aurora Mateos. La infracción de los derechos mencionados puede ser constitutiva de delito contra la propiedad intelectual y puede asimismo dar lugar a las acciones administrativas y civiles correspondientes 2 A R Roger,oger, por las cosas que pasan en RomaRoma.... RAPHAEL URBINAS QUOD NATURA ABSTULERAT, ARTE RESTITUIT 1. Tu sai perché, senza vengarlo in carte 2, Ch´io dimostrai il contrario del mio cuore. 1 “Rafael de Urbino, lo que la naturaleza quitara, el arte lo restituye”, inscripción en la tumba del elefante Annone, regalado por el rey Emmanuel de Portugal al Papa León, y que Rafael pintó en la “Stanza della Segnatura” del Vaticano. 2 Soneto n.IV de Raffaelo: “Tú sabes sin que yo lo niegue por carta, por qué demuestro el contrario de mi corazón”. Actualmente en el dibujo PII 546 del Ashmolean Museum de Oxford . 3 AGRADECIMIENTOS: A la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Cambridge (Reíno Unido) y del Magdalene College , por dejarme acceder a sus archivos; al profesor Eamon Duffy por sus consejos eclesiásticos; al teatro Echegaray de Málaga, por incluir la primera lectura dramatizada de la obra en el XXVI festival internacional de teatro; a Francisca Medina (Universidad de Granada) por el estudio sobre los tratamientos protocolarios de los personajes; a Ignacio del Moral por ser amigo y maestro; y particularmente a Boomie Petersen, Peter Coy y Rick Hite, Director, Dramaturgista y traductor en la “Virginia Playwrights & Screenwriters Initiative, VPSI” del Teatro Hamner en Estados Unidos, a quienes esta obra y yo estamos en deuda. -

Paul Barlow Imagining Intimacy

J434 – 01-Barlow 24/3/05 1:06 pm Page 15 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link Paul Barlow Imagining Intimacy: Rhetoric, Love and the Loss of Raphael This essay is concerned with intimacy in nineteenth-century art, in particular about an imagined kind of intimacy with the most admired of all artists – Raphael. I will try to demonstrate that this preoccupation with intimacy was a distinctive phenomenon of the period, but will concentrate in particular on three pictures about the process of painting emotional intimacy, all of which are connected to the figure of Raphael. Raphael was certainly the artist who was most closely associated with this capacity to ‘infuse’ intimacy into his art. As his biographers Crowe and Cavalcaselle wrote in 1882, Raphael! At the mere whisper of the magic name, our whole being seems spell-bound. Wonder, delight and awe, take possession of our souls, and throw us into a whirl of contending emotions … [He] infused into his creations not only his own but that universal spirit which touches each spectator as if it were stirring a part of his own being. He becomes familiar and an object of fondness to us because he moves by turns every fibre of our hearts … His versatility of means, and his power of rendering are all so varied and so true, they speak so straightforwardly to us, that we are always in commune with him.1 It is this particular ‘Raphaelite’ intimacy that I shall be exploring here, within the wider context of the transformations of History Painting in the period. -

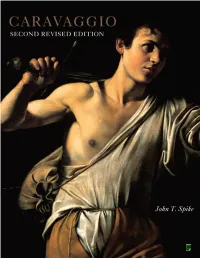

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio. -

COVER NOVEMBER Prova.Qxd

54-55 Lucy Art RAPHAEL Apri20 corr1_*FACE MANOPPELLO DEF.qxd 3/24/20 11:58 AM Page 54 Of Books, Art and People RAPHAEL SUPERSTAR n On this page, Raphael’s self-portrait; and BY LUCY GORDAN Madonna del Granduca; Portrait of Pope Leo X with Two Cardinals ith over 70,000 ad - One loan is Raphael’s realistic vance ticket sales Uffizi Portrait of Pope Leo X with Two Cardi - from all over the Commissioned by the W nals (c. 1517). world and, as of this writing Pope himself and painted in Rome, it was (in late February) no cancelations a wedding present for his nephew Loren - in spite of coronavirus, the mega- zo, the Duke of Urbino, who fathered show three years in the planning Catherine who became Queen of France, “Raf - was opened on and so ended up in the . The cardi - faello 1520-1483” Uffizi March 3 by Sergio Mattarella, the nal on the left is the Pope’s nephew, Giu - president of Italy. To celebrate the liano de’ Medici (future Pope Clement 500th death anniversary of the “ VII); the other is Cardinal Luigi de’ divin or “ Rossi, a maternal cousin. It was especial - pictor” dio mortale” (“mortal as his contemporary artist-bi - ly restored for “ at the God”) Raffaello” Opificio ographer Giorgio Vasari called in Florence delle Pietre Dure . Raphael, it’s on in the Quirinal’s The other paintings by Raphael Uffizi until June 2. [ : are his , Scuderie Note The gov - San Giovanni Battista La Velata, perhaps a portrait of Raphael’s great love ernment announced in early March .] Margherita Luti; a portrait of the closing of the show until April 3 due to the virus Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi On display are 240 works-of-art; 120 of them (includ - (1470-1520), a patron of Raphael, a close da Bibbiena ing the based on his advisor to Pope Leo X and the uncle of Raphael’s official Tapestry of The Sacrifice of Lystra cartoons and his letter to Medici-born Pope Leo X, reign but not beloved fiancée; Ezekiel’s Vision, Madonna del 1513-21, about the importance of preserving Rome’s an - and a portrait of Granduca Madonna dell’Impannata, tiquities) are by Raphael himself. -

Senior Thesis Essay

Ingres’ Raphael and La Fornarina: The Marriage of Classicism and Romanticism Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in History of Art in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Benjamin Shehadi The Ohio State University April 2021 Project Advisor: Professor Andrew Shelton, Department of History of Art The romance between Raphael and the Fornarina is, in the words of humanities scholar Marie Lathers, “the archetypal artist-model relationship of Western tradition.”1 Nowhere is this classic story more tenderly and iconically depicted than in Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Raphael and La Fornarina series. Ingres’ masterful paintings perfectly harmonized elements from the competing Neoclassical and Romantic art traditions in the early and mid 19th century. In these works, Ingres imbued the Classical heritage, as exemplified by Raphael’s art, with a new sense of Romantic emotionalism and individuality. In this way, Ingres forged a distinctive style of Romantic Classicism, which solidified his status among the pantheon of great Western painters. Raphael, The Lover Vasari’s Lives speaks of Raphael’s infatuation with his mistress: “Raffaello was a very amorous person, delighting much in women, and ever ready to serve them; which was the reason that, in the pursuit of his carnal pleasures, he found his friends more complacent and indulgent towards him than perchance was right. Wherefore, when his dear friend Agostino Chigi commissioned him to paint the first loggia in his palace, Raffaello was not able to give much attention to his work, on account of the love that he had for his mistress.”2 According to Vasari’s account, Raphael was distracted by the love of his mistress during his work on Agostino Chigi’s villa. -

Raphael Santi London

RAPHAEL SANTI LONDON PRINTED BY SPOTTISWOODE AND CO. NEW-STEEET SQUARE RAPHAEL SANTI His Life and His Works BY ALFRED BARON VON WOLZOGEN TRANSLATED BY F. E. BUNNETT TRANSLATOR OF GRIMM'S ' LIFE OF MICHAEL ANGELO' AND GERVINUS'S 'SHAKESPEARE COMMENTARIES LONDON SMITH, ELDER, & CO., 65 CORNHILL 1866 759.5 R12wEb TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE. HAVING translated Grimm's 'Life of Michael Angelo,' I was desirous of finding some memoir of his great contemporary Eaphael, which might complete the picture we already possess of a period so rich in the history of Art. It was not easy to meet with a work which was not too diffuse in its art-criticisms for the ordinary reader, and until Wolzogen's 'Life of Eaphael' appeared, there was no concise biography of the great painter which seemed to me to supply the information required. It is for this reason that I have translated the work; and I trust it will not be without interest to those who have hitherto known Eaphael in his art alone. F. E. BUNNETT. PREFACE. EAPHAEL-LITERATURE already fills a library of its own. Extensive works, such as Passavant's ' Eafael von Urbino und sein Vater Giovanni Santi' (three volumes, with maps, Leipsic, 1839-58), are among its treasures; but there is ever lacking a concise summary of all the more important investigations and decisions hitherto arrived at with regard to the great master's life and works. The best and most spirited of these are for the most part, moreover, in various papers and pamphlets, in which Eaphael is not the sole subject. -

Raffaello E Le Sue Reincarnazioni

Originalveröffentlichung in: Atti e studi: NS, 1 (2006), S. 5-30 RAFFAELLO E LE SUE REINCARNAZIONI SYBILLE EBERT-SCHIFFERER Sappiamo bene come per secoli la lode più alta che quello con Zeusi(2), alla cui arte sono legati sin dalla si potesse fare a un pittore era di confrontarlo ai letteratura artistica antica le nozioni di venustas (o due sommi pittori dell ’Antichità, Apelle e Zeusi. charis) e grazia-, 2) il paragone con Zeusi, più speci- Raffaello Sanzio non è l’unico a cui fu fatto questo fìco in quanto legato alla leggenda delle cinque ver- onore, ma è forse l’unico al quale, nel corso dei gini di Crotone dalle quali trasse la bellezza della secoli, fu concesso lo stesso ruolo di punto di riferi- sua Elena, leggenda alla quale il Sanzio stesso, in mento assoluto con cui paragonarsi sia stilistica- una sua lettera, avrebbe legato la nozione della mente sia, per certi casi, biograficamente. Vorrei “certa idea ”, che ebbe tanta fortuna nella dottrina esaminare acuni esempi di questo processo che accademica del classicismo, traduzione di un con- portò, sotto vari punti di vista, alla sostituzione cetto ciceroniano di Giovanni Francesco Pico(3); 3) delle figure di Apelle o Zeusi con quella di l’elevazione a “divino”e, fmalmente, 4) il trasferi- Raffaello. Mentre si tratta, spesse volte, di valuta- mento, operato sin dal Vasari, delle caratteristiche zioni o elogi espressi da teorici o biografi, si verifi- riconosciute alle sue opere, al suo carattere e alla cano anche casi in cui l’emulazione è voluta dagli sua condotta di vita, nell’interesse della costruzione stessi artisti; dalla seconda metà del Settecento, si di una perfetta kalokagatia (che fìnisce per essere assiste alla proiezione e modellazione di intere bio- eterna giovinezza). -

RAFFAELLO SANZIO Di Carla Amirante

RAFFAELLO SANZIO di Carla Amirante 2020 è l’anno in cui ricorre il quinto centenario della morte di Raffaello Sanzio pittore e architetto tra i più grandi artisti di tutti i tempi, considerato come un esempio perfetto della pittura del Rinascimento italiano. Con i suoi dipinti caratterizzati da un giusto equilibrio compositivo e da una raffinata ricerca formale il Sanzio ha saputo creare opere così serene e concluse, prive dell'ambiguità leonardesca e del dramma michelangiolesco, tali da apparire inafferrabili e divine. Nella sua attività Raffaello fu aiutato da un bell’aspetto, una personalità amabile, educata e raffinata, ma essendo anche molto ambizioso seppe unire a queste sue doti naturali anche un talento straordinario e una capacità organizzativa, di tipo imprenditoriale, quasi moderna tale che in pochi anni di carriera riuscì ad ottenere grandissima fama e notevole ricchezza. Neppure Leonardo e Michelangelo erano riusciti ad ottenere altrettanto. Di eccezionale apertura mentale, Raffaello continuò anche in età matura a migliorare la sua formazione artistica seguendo più strade, interessandosi alla cultura del suo tempo e studiando altri artisti. Egli prese contatto con i protagonisti del pensiero neoplatonico e strinse amicizia con letterati e intellettuali per arricchire al massimo la sua personalità, utilizzando e rielaborando le loro idee e saperi per dare così altra linfa alla sua già feconda creatività. Raffaello riuscì a fondere così la più alta tradizione quattrocentesca con gli elementi innovativi del ‘500 in una personale visione unitaria e, avendo inoltre grande padronanza dei mezzi espressivi, portò nelle sue opere un linguaggio chiaro, preciso e dallo stile inconfondibile. Per i pittori venuti dopo di lui Raffaello divenne quindi il modello assoluto a cui fare riferimento e fu considerato il creatore della pittura “all’antica”, influenzando profondamente sia l’arte del suo tempo che quella venuta dopo di lui, la corrente artistica che va sotto il nome di Manierismo.