Bedford-Stuyvesant and Downtown Brooklyn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downtown Rising: Rising: 02.2016 02.2016 Howhow Brooklyn Brooklyn Became Became a Model a Model for for Urbanurban Development Development

DowntownDowntown Rising: Rising: 02.2016 02.2016 HowHow Brooklyn Brooklyn became became a model a model for for urbanurban development development 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 11 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 -

An Economic Snapshot of the Greater Downtown Brooklyn Area

An Economic Snapshot of the Greater Downtown Brooklyn Area Thomas P. DiNapoli Kenneth B. Bleiwas New York State Comptroller Deputy Comptroller Report 5-2013 July 2012 The greater downtown Brooklyn area is the civic Highlights center of Brooklyn and includes the largest business district in New York City outside of • Private sector employment in the greater Manhattan. With its close proximity to Manhattan downtown Brooklyn area rose by and excellent transportation options, the area 18.3 percent between 2003 and 2010. offers a lower-cost business district that has • Health care and social assistance is the attracted large and small firms in a wide range of largest employment sector, accounting for sectors. nearly one-third of the area’s private sector jobs in 2010. Job growth in the area has been robust, outperforming the rest of Brooklyn and the rest of • The business and finance sectors together the City between 2003 and 2010. Although more accounted for 21.3 percent of the area’s recent neighborhood data are not available, it private sector jobs in 2010. appears that the greater downtown Brooklyn area • The educational services sector accounted continues to experience strong job growth. for nearly 11 percent of all private sector Together, business, finance and educational jobs, reflecting the area’s concentration of services account for one-third of the area’s jobs, colleges and universities. This sector grew by which is almost twice their share in the rest of nearly one-quarter between 2003 and 2010. Brooklyn. High-tech businesses also have taken a • Employment in the leisure and hospitality foothold in the area. -

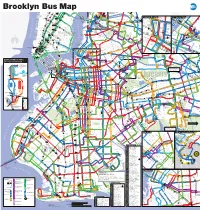

Brooklyn Bus Map

Brooklyn Bus Map 7 7 Queensboro Q M R Northern Blvd 23 St C E BM Plaza 0 N W R W 5 Q Court Sq Q 1 0 5 AV 6 1 2 New 3 23 St 1 28 St 4 5 103 69 Q 6 7 8 9 10 33 St 7 7 E 34 ST Q 66 37 AV 23 St F M Q18 to HIGH LINE Chelsea 44 DR 39 E M Astoria E M R Queens Plaza to BROADWAY Jersey W 14 ST QUEENS MIDTOWN Court Sq- Q104 ELEVATED 23 ST 7 23 St 39 AV Astoria Q 7 M R 65 St Q PARK 18 St 1 X 6 Q 18 FEDERAL 32 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 102 Long 28 St Q Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 27 MADISON AV E 28 ST Roosevelt Av BUILDING 67 14 St A C E TUNNEL 32 44 ST 58 ST L 8 Av Hunters 62 70 Q R R W 67 G 21 ST Q70 SBS 14 St X Q SKILLMAN AV E F 23 St E 34 St / VERNON BLVD 21 St G Court Sq to LaGuardia SBS F Island 66 THOMSO 48 ST F 28 Point 60 M R ED KOCH Woodside Q Q CADMAN PLAZA WEST Meatpacking District Midtown Vernon Blvd 35 ST Q LIRR TILLARY ST 14 St 40 ST E 1 2 3 M Jackson Av 7 JACKSONAV SUNNYSIDE ROTUNDA East River Ferry N AV 104 WOODSIDE 53 70 Q 40 AV HENRY ST N City 6 23 St YARD 43 AV Q 6 Av Hunters Point South / 7 46 St SBS SBS 3 GALLERY R L UNION 7 LT AV 2 QUEENSBORO BROADWAY LIRR Bliss St E BRIDGE W 69 Long Island City 69 St Q32 to PIERREPONT ST 21 ST V E 7 33 St 7 7 7 7 52 41 26 SQUARE HUNTERSPOINT AV WOOD 69 ST Q E 23 ST WATERSIDE East River Ferry Rawson St ROOSEV 61 St Jackson 74 St LIRR Q 49 AV Woodside 100 PARK PARK AV S 40 St 7 52 St Heights Bway Q I PLAZA LONG 7 7 SIDE 38 26 41 AV A 2 ST Hunters 67 Lowery St AV 54 57 WEST ST IRVING PL ISLAND CITY VAN DAM ST Sunnyside 103 Point Av 58 ST Q SOUTH 11 ST 6 3 AV 7 SEVENTH AV Q BROOKLYN 103 BORDEN AV BM 30 ST Q Q 25 L N Q R 27 ST Q 32 Q W 31 ST R 5 Peter QUEENS BLVD A Christopher St-Sheridan Sq 1 14 St S NEWTOWN CREEK 39 47 AV HISTORICAL ADAMS ST 14 St-Union Sq 5 40 ST 18 47 JAY ST 102 Roosevelt Union Sq 2 AV MONTAGUE ST 60 Q F 21 St-Queensbridge 4 Cooper McGUINNESS BLVD 48 AV SOCIETY JOHNSON ST THE AMERICAS 32 QUEENS PLAZA S. -

Affordable Housing for Rent

Affordable Housing for Rent 33 BOND STREET APARTMENTS 143 NEWLY CONSTRUCTED UNITS AT 33 Bond Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201 Downtown Brooklyn Amenities: 24-hour attended lobby, on-site resident manager, sun terrace, fitness center†, computer lounge†, dog grooming†, party rooms†, laundry room†, bike storage† (†additional fees apply). Transit: Trains - 2/3/4/5/A/B/C/G/Q, Buses - B25/B26/B38/B52 No application fee • No broker’s fee • Smoke-free building • More information: nyc.gov/housingconnect This building is being constructed through the Inclusionary Housing Program and is approved to receive a Tax Exemption through the 421- a Program of the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development and the 80/20 New Construction Housing Program of the New York State Homes and Community Renewal. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Who Should Individuals or households who meet the income A percentage of units is set aside for: Apply? and household size requirements listed in the Mobility - disabled applicants (5%) table below may apply. Qualified applicants will Vision - or hearing - disabled applicants (2%) be required to meet additional selection criteria. Preference for a percentage of units goes to: Applicants who live in New York City receive a Residents of Community Board #2 (50%) general preference for apartments. Municipal employees (5%) * Up to half of CB preference units may be allocated through referrals of applicants from city agencies AVAILABLE UNITS AND INCOME REQUIREMENTS 3 1 2 Annual Household Income Unit Size Monthly Rent Units Available Household Size Minimum – Maximum4 Studio $897 51 → 1 person $32,640 - $38,100 1 person $34,972 - $38,100 1 bedroom UNITS $963 52 → 2 people $34,972 - $43,500 (AMI) (AMI) 2 people $41,966 - $43,500 2 bedroom $1,166 40 → 3 people $41,966 - $48,960 0% AREA MEDIAN INCOME INCOME MEDIAN AREA 0% 6 4 people $41,966 - $54,360 1 Rent includes gas for cooking. -

Narrative Summary of Constraints and Opportunities Provided to the Panel by NYC DOT

As presented to the BQE Expert Panel for informational/background purposes only https://bqe-i278.com/en/expert-panel/documents Narrative Summary of Constraints and Opportunities Provided to the panel by NYC DOT What Makes the Project So Complicated? Fixing the BQE is exceptionally complicated due to its unusual design and the constrained site in which it operates. This corridor is sandwiched between Brooklyn Bridge Park, the Promenade and Brooklyn Heights, the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges, bustling DUMBO and Vinegar Hill, and an extraordinary volume of infrastructure below – four subway lines, an eight-foot DEP interceptor sewer, and many other utility lines. Creating sufficient space to stage the construction (e.g. to fit equipment like cranes and store materials) is a key challenge that any concept must address. Specifically, any construction concept needs to account for the complexities of working with a cantilever structure, building on or around Furman Street, the surrounding open spaces, and other infrastructure running above and below the BQE. This part of the BQE corridor is also comprised of multiple structures that require different methods of rehabilitation or replacement. Although the triple cantilever is the most well-known portion of this project, the double cantilever and the bridges at Joralemon, Old Fulton, and Columbia Heights all require repair. Cantilever Considerations A traditional bridge structure is usually rehabilitated lane-by-lane. Construction crews shut down a portion of the bridge, repair those areas, and then shift traffic to the rehabilitated section. This type of construction staging is not possible on the triple cantilever due to the unique nature of the BQE. -

Summer Camp Guide 2018 Summer Camps Easily Accessible from Brooklyn Heights, DUMBO, Downtown Brooklyn, Bococa and Beyond

Summer Camp Guide 2018 Summer camps easily accessible from Brooklyn Heights, DUMBO, Downtown Brooklyn, BoCoCa and beyond This comprehensive summer camp guide profiles 50 local summer camps in Brooklyn Heights, DUMBO, Downtown Brooklyn, Gowanus, BoCoCa and beyond! We have listed program details, age groups, dates, hours, costs and contact information for each camp for children 18 months to 18 years old. The guide includes arts, animation, circus, cooking, engineering, fashion design, movie making, swimming, skateboarding, tennis, theater, STEM, and textile camps. It also features French, Spanish, Hebrew, Italian and Mandarin immersion summer programs in our neighborhood and much more! Animation & Music Camp Program: In our Stop Motion Animation camp young creators ages 5-9 will learn and create original animation movies and engage in activities designed to cultivate curiosity, creativity, self- expression and friendship. They are guided through the steps of producing movies with cool themes, titles, sound effects and a whole host of unique features and work with variety of materials to create their stop-motion’s objects, sets, figures, props, sequential drawing or animate toys. Our enriching summer experience is designed so that children additionally to movie making explore sound, music, drumming, martial arts and other activities indoor and outdoor including a daily recess at the John Street lawn in Brooklyn Bridge Park. Small group limited to 6 campers a day. Students are required to bring their own iPad or iPhone to camp with the appropriate -

Brooklyn Night Bus

BBrrookkllyynn BBuuss Night Night M Mapap 1:00 AM to 5:00 AM Q 23 St ae E Northern Blvd nq 46 100 Queensboro Plaza CHELSEA 12 28 St 33 St Q n7 23 St Q 66 f MADISON AV Court Sq 39 E Queens Plaza HIGH LINE W 14 ST 23 St 46 7 23 St 65 St EIGHTH AV E E 37 AV 12 28 St HUNTERS 39 AV FEDERAL 36 AV ELEVATED 62 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn Court Sq 7 Q Downtown Brooklyn BUILDING LIC / Queens Plaza New Jersey PARK ae L 8 Av 18 St POINT 32 Roosevelt Av 14 St nq G 70 X Q70 SBS E 38 AV 23 St E 34 St / 21 St G Court Sq Q to LaGuardia SBS CADMAN PLAZA WEST 14 St 28 LEXINGTON AV THOMSO 46 ST Midtown 60 Q Q F ED KOCH 12 f Vernon Blvd - WOODSIDE TILLARY ST 14 St SUNNYSIDE 35 ST ROTUNDA East River Ferry Jackson Av N AV LIRR 53 70 Q 46 JACKSON AV YARD 39 ST 6 Av L Hunters Point South / 7 WOODSIDE SBS SBS GALLERY 26 62 66 23 St 42 ST QUEENSBORO BRIDGE UNION Long Island City 52 41 23 ST ST 7 33 St- 7 74 St- SQUARE LIRR Q 7 7 PIERREPONT ST Q BROADWAY E 23 ST WATERSIDE Rawson St 7 Bway East River Ferry HUNTERSPOINT AV 32 69 St Q LONG PARK LIRR 30 PL 100 PLAZA 7 7 40 St 7 52 St 61 St - 38 26 LONG Lowery St Woodside 32 ISLAND ISLAND Hunters SUNNYSIDE 7 Q IRVING PL 3 AV McGUINNESS BLVD Point Av 58 ST BROOKLYN 14 St- 11 ST Q CHRISTOPHER ST SEVENTH AV nql CITY 46 St QUEENS BLVD Q 60 Q 21 ST CITY Union Sq 30 ST HISTORICAL FAMILY QUEENS PLAZA S PETER 39 Bliss St 63 ST 1 2 AV 25 102 ROOSEVELT 101 21 St VAN DAM SOCIETY NY STATE JOHNSON ST F CRESCENT ST Christopher St 12 l 3 Av COOPER Q MONTAGUE ST COURT Queensbridge Sheridan Sq 48 AV 44 AV SUPREME 25 ISLAND VILLAGE -

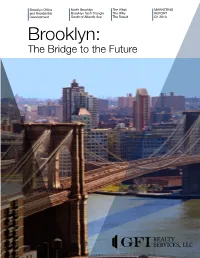

Brooklyn Bus Map

Brooklyn Bus Map To E 5757 StSt 7 7 Q M R C E BM Queensboro N W Northern Blvd Q Q 100 Plaza 23 St 23 St R W 5 5 AV 1 28 St 6 E 34 ST 103 69 Q WEST ST 66 33 St Court Sq 7 7 Q 37 AV Q18 to 444 DR 9 M CHELSEA F M 4 D 3 E E M Queens Astoria R Plaza Q104 to BROADWAY 23 St QUEENS MIDTOWN7 Court Sq - Q 65 St HIGH LINE W 14 S 23 ST 23 St R 7 46 AV 39 AV Astoria 18 M R 37 AV 1 X 6 Q FEDERAL 36 ELEVATED T 32 62 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza AV 47 AV D Q Downtown Brooklyn BUILDING 67 LIC / Queens Plaza 27 1 T Q PARK 18 St MADISON28 AVSt 32 ST Roosevelt Av 14 St A C E TUNNEL G Court Sq 58 ST 70 R W 67 212 ST 102 E ST 44 Q70 SBS L 8 Av X 28 S Q 6 S E F 38 T 4 TILLARY ST E 34 St / HUNTERSHUNTER BLV21 StSt G SKILLMAN AV SBS 103 AV 28 23 St VERNON to LaGuardia BACABAC F 14 St LEXINGTON AV T THOMSO 0 48 T O 6 Q Q M R ED KOCH Midtown 9 ST Q CADMAN PLAZA F M VernonVe Blvdlvd - 5 ST T 37 S WOODSIDE 1 2 3 14 St 3 LIRRRR 53 70 POINT JaJ cksonckson AvAv SUNNYSIDE S 104 ROTUNDA Q East River Ferry N AV 40 ST Q 2 ST EIGHTH AV 6 JACKSONAV QUEENS BLVD 43 AV NRY S 40 AV Q 3 23 St 4 WOODSIDEOD E TILLARY ST L 7 7 LIRR YARD SBS SBS 32 GALLERY 26 H N 66 23 Hunters Point South / 46 St T AV HE 52 41 QUEENSBORO 9 UNION E 23 ST M 7 L R 6 BROADWAY BRIDGEB U 6 Av HUNTERSPOINT AV 7 33 St- Bliss St E 7 Q32 E Long Island City A 7 7 69 St to 7 PIERREPONT ST W Q SQUARE Rawson St WOOD 69 ST 62 57 D WATERSIDE 49 AV T ROOSEV 61 St - Jackson G Q Q T 74 St- LONG East River Ferry T LIRR 100 PARK S ST 7 T Woodside Bway PARK AV S S 7 40 St S Heights 103 1 38 26 PLAZA -

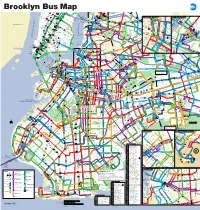

Brooklyn: the Bridge to the Future TABLE of CONTENTS • MARKETING REPORT • Q1 2016

Brooklyn Offce North Brooklyn The What MARKETING and Residential Brooklyn Tech Triangle The Why REPORT Development South of Atlantic Ave The Result Q1 2016 Brooklyn: The Bridge to the Future TABLE OF CONTENTS • MARKETING REPORT • Q1 2016 Brooklyn: The Bridge to the Future 1 A boom in living and working in Brooklyn: What’s driving it? - 2 3 North Brooklyn: - Greenpoint | Williamsburg | Bushwick 4 - 5 6 Brooklyn Tech Triangle: - Dumbo | Downtown Brooklyn | Brooklyn Navy Yard 7 - 8 9 South of Atlantic Ave: What’s Next? - Gowanus | Red Hook | Sunset Park 10 - 11 The Result 12 13 Recent Sales | Contact | About GFI Realty Services - 14 140 BROADWAY 41ST FLOOR | NEW YORK, NY 10005 P: (212) 837.4665 | E: [email protected] INTRODUCTION • MARKETING REPORT • Q1 2016 1 A boom in living and working in Brooklyn: What’s driving it? Due to Brooklyn’s exponential year-over-year residential and retail growth, combined with the staggering number of units in the pipeline, it’s nearly impossible to ignore the development currently taking place in Brooklyn. With the explosive growth of the borough’s population, particularly among millennials, and the borough’s emergence as an incubator for TAMI (Technology, Advertising, Media and Innovation) companies, we are seeing waves of developers “crossing the bridge” as they seek new investment opportunities. his trend began in Northern Brooklyn, with Tthe emergence of neighborhoods such as Greenpoint, Williamsburg and Bushwick, Residential 2015 By end of 2016 and has moved south, particularly in water- Growth front neighborhoods, to the Navy Yard, Down- 2,700 5,000 town Brooklyn, DUMBO, Gowanus, Red Hook and Sunset Park. -

S.O.S. Bed-Stuy Guide to Community Resources, Services and Organizations

S.O.S. Bed-Stuy Guide to Community Resources, Services and Organizations BED-STUY CONTENTS S.O.S. BED-STUY — 3 CROWN HEIGHTS COMMUNITY MEDIATION CENTER — 4 HISTORY OF BED-STUY — 5 ADULT EDUCATION — 6 BUSINESS AND ENTREPRENEUR RESOURCES — 7 CAREER COUNSELING AND TRAINING PROGRAMS — 8 COMMUNITY CENTERS — 11 CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS — 12 DOMESTIC VIOLENCE RESOURCES — 15 FINANCIAL ADVICE — 19 LGBTQ RESOURCES — 21 DAYCARE CENTERS AND HEAD START — 23 HEALTH — 24 HIV/AIDS SERVICES — 27 HOMELESSNESS — 29 HOUSING — 31 HUNGER — 33 LEGAL SERVICES — 35 MEDIATION AND DISPUTE RESOLUTION — 38 MENTAL HEALTH RESOURCES — 39 RE-ENTRY SERVICES AND RESOURCES — 41 SENIOR, VETERAN, AND DISABLED SERVICES — 42 SUBSTANCE ABUSE — 45 YOUTH PROGRAMS AND FAMILY RESOURCES — 48 AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS — 49 AND ACTIVITIES — 49 FATHERHOOD PROGRAMS — 52 FAMILY RESOURCES — 53 USEFUL GOVERNMENT NUMBERS — 55 ELECTED OFFICIALS AND GOVERNMENT REPRESENTATIVES — 57 2 S.O.S. Bed-Stuy Guide to Community Resources, Services and Organizations S.O.S. BED-STUY Save Our Streets (S.O.S.) is a community-based effort to end gun violence. S.O.S. staff prevent gun violence from occurring in the program target areas by mediating conflicts that may end in gun violence and acting as peer counselors to men and women who are at risk of perpetrating or being victimized by violence. S.O.S. works closely with neighborhood leaders and businesses to promote a visible and public message against gun violence, encouraging local voices to articulate that shooting is an unacceptable behavior. The Save Our Streets staff is comprised of Outreach Workers and Violence Interrupters. The outreach staff all have first-hand knowledge of street life and gang life and live in or near the program target area. -

Our Neighborhood Conversations with and Honors for Park Slope Leaders of Today and Tomorrow

Civic News Summer 2011 The Newsletter of the Park Slope Civic Council | www.parkslopeciviccouncil.org The People in Our Neighborhood Conversations with and honors for Park Slope leaders of today and tomorrow Joe Holtz: Good Food, Cooperation, and Comment Community Service Getting Our Voices into Atlantic Yards Mort Fleisher: Four Decades of News & Notes Working for a Better Slope inside ... inside General Meeting Showcases Major Successes in the Community Emily Lloyd: A New Leader for Prospect Park United for a New Megaproject Model Comment Getting Our Voices into Atlantic Yards The Atlantic Yards project is the single most transfor- project, likely to be built over the span of two decades. The mative construction in the Downtown/Brownstone Brook- project sponsor, the Empire State Development Corporation lyn area in more than 50 years. The project is in the same (ESDC), is a state agency and at present is accountable only league as the clearing of many blocks of Downtown Brook- to the governor. There is no formal process for public in- lyn starting in the late 1930s to make way for the Civic volvement, only the fig leaf of a community outreach office, Center and Cadman Plaza, the construction of the Brook- whose liaison position is vacant as this is written. lyn-Queens Expressway, and the development of huge pub- On the legal front, BrooklynSpeaks, Develop Don’t De- lic housing projects to the west and south of the Brooklyn stroy Brooklyn (DDDB), and others have filed a lawsuit Navy Yard. They all drastically changed the face of Brooklyn against the ESDC over the modified project scope and sched- in their time, and Atlantic Yards stands to do the same. -

FORT GREENE and BROOKLYN HEIGHTS (Including Boerum Hill, Brooklyn Heights, Clinton Hill, Downtown Brooklyn, DUMBO, Fort Greene and Vinegar Hill)

COMMUNITY HEALTH PROFILES 2015 Brooklyn Community District 2: FORT GREENE AND BROOKLYN HEIGHTS (Including Boerum Hill, Brooklyn Heights, Clinton Hill, Downtown Brooklyn, DUMBO, Fort Greene and Vinegar Hill) Health is rooted in the circumstances of our daily lives and the environments in which we are born, grow, play, work, love and age. Understanding how community conditions affect our physical and mental health is the first step toward building a healthier New York City. FORT GREENE AND BROOKLYN HEIGHTS TOTAL POPULATION WHO WE ARE 102,814 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 POPULATION BY RACE AND ETHNICITY 46%e Whit * 27% Black* 14% Hispanic 8% Asian* 4% Other* Population BY AGE HAVE LIMITED 44% ENGLISH NYC 20% PROFICIENCY 20% 15% NYC 10% 10% 11% ARE 0–17 18–24 25–44 45–64 65+ FOREIGN 0 - 17 18-24 25-44 45-64 65+ BORN Percent WHO REPORTED THEIR OWN health AS “EXCELLENT,” LIFE EXPECTANCY ”VERY GOOD” OR “GOOD” 79.4 84% YEARS * Non-Hispanic Note: Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding Sources: Overall population, race and age: U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates, 2013; Foreign born and English proficiency: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2011-2013; Self-reported health: NYC DOHMH Community Health Survey, COMMUNITY2011-2013; Life Expectancy: HEALTH NYC DOHMH PROFILESBureau of Vital Statistics, 2015: 2003-2012 FORT GREENE AND BROOKLYN HEIGHTS 2 Note from Dr. Mary Bassett, Commissioner, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene New York City is a city of neighborhoods. Their diversity, rich history and people are what make this city so special.