Dalrev Vol16 Iss1 Pp5 15.Pdf (6.196Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Leonard Tilley

SIR LEONARD TILLEY JAMES HA NNAY TORONTO MORANG CO L IMITE D 1911 CONTENTS EARLY LIFE AND B' SINESS CAREER ELECTED T0 THE LEGISLAT' RE CHAPTER III THE PROHIBITORY LI' ' OR LAW 29 CHAPTER VI THE MOVEMENT FOR MARITIME ' NION CONTENTS DEFEAT OF CONFEDERATION CHAPTER I' TILLEY AGAIN IN POWER CHAPTER ' THE BRITISH NORTH AMERICA ACT CHA PTER ' I THE FIRST PARLIAMENT OF CANADA CHAPTER ' II FINANCE MINISTER AND GO VERNOR INDE' CHAPTER I EARLY LIFE AND B' SINESS CAREER HE po lit ic al c aree r of Samuel Leonard Tilley did not begin until the year t hat bro ught the work of L emuel Allan Wilmot as a legislator to a we e elect ed e bers t he close . Both r m m of House of 1 850 t he l ea Assembly in , but in fol owing y r Wil elev t ed t o t he benc h t h t t he mot was a , so a province lost his services as a political refo rmer just as a new t o re t man, who was destined win as g a a reputation t he . as himself, was stepping on stage Samuel l at t he . Leonard Til ey was born Gagetown , on St 8th 1 8 1 8 i -five John River, on May , , just th rty years after the landing of his royalist grandfather at St. - l t . e John He passed away seventy eight years a r, ull t he f of years and honours , having won highest prizes that it was in the power of his native province t o bestow. -

Canada and Its Provinces in Twenty-Two Volumes and Index

::;:i:;!U*-;„2: UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES (SDi'nbutgf) (ZBDition CANADA AND ITS PROVINCES IN TWENTY-TWO VOLUMES AND INDEX VOLUME X THE DOMINION INDUSTRIAL EXPANSION PART II The Edinburgh Edition of ' Caxada and its Provinces' is limited to Sjs Impressions on All- Rag Watermarked Paper This Impression is Nuviber /.iP..t> LORD STRATHCONA AND MOUNT ROYAL From a photograph by Lafayette CANADA AND ITS PROVINCES A HISTORY OF THE CANADIAN PEOPLE AND THEIR INSTITUTIONS BY ONE HUNDRED ASSOCIATES GENERAL EDITORS: ADAM SHORTT AND ARTHUR G. DOUGHTY VOLUME X THE DOMINION INDUSTRIAL EXPANSION EDINBURGH EDITION PRINTED BY T. ds" A. CONSTABLE AT THE EDINBURGH UNIVERSITY PRESS EOR THE PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION OF CANADA LIMITED TORONTO 1914 . t ( * * " Copyright in all countries subscribing to the Berne Convention — F V. I O CONTENTS rAOK NATIONAL HIGHWAYS OVERLAND. By S. J. MLean I. EARLY GENERAL HISTORY ...... 359 Highways and Highway Travel— Beginnings of Railways n. THE MARITIME PROVINCES ..... 378 The Halifax and Quebec Project—The European and North American Project in. THE CANADAS ....... 39I Railway Policy of Francis Hincks—Railway Expansion in the Canadas IV. CONFEDERATION AND RAILWAY EXPANSION . -417 The Intercolonial—The Canadian Pacific—Railway Develop- ment in Ontario —Quebec Railway Projects— Rate Wars The Gauge Problem V. THE GOVERNMENT AND THE RAILWAYS .... 432 Eastern Expansion of the Canadian Pacific — The Grand Trunk "'. the Canadian Pacific— Manitoba and the Canadian Pacific—The Dominion and the Provinces—The Dominion Subsidy Policy VL RECENT RAILWAY DEVELOPMENT. .... 449 The Influence of 'Wheat'— British Columbia and the Yukon —The Canadian Northern—The Grand Trunk Pacific—The Great Northern in Canada—Government Railways—Govern- ment Aid— Railway Rates—The Board of Railway Com- missioners SHIPPING AND CANALS. -

GEORGE BROWN the Reformer

GEORGE BROWN The Reformer by Alastair C.F. Gillespie With a Foreword by the Hon. Preston Manning Board of Directors Richard Fadden Former National Security Advisor to the Prime Minister and former Deputy Minister of National Defence CHAIR Rob Wildeboer Brian Flemming Executive Chairman, Martinrea International Inc. International lawyer, writer, and policy advisor Robert Fulford VICE CHAIR Former Editor of Saturday Night magazine, columnist with Jacquelyn Thayer Scott the National Post Past President and Professor, Wayne Gudbranson Cape Breton University, Sydney CEO, Branham Group Inc., Ottawa MANAGING DIRECTOR Stanley Hartt Brian Lee Crowley Counsel, Norton Rose LLP SECRETARY Calvin Helin Lincoln Caylor International speaker, best-selling author, entrepreneur Partner, Bennett Jones LLP, Toronto and lawyer. TREASURER Peter John Nicholson Martin MacKinnon Former President, Canadian Council of Academies, Ottawa CFO, Black Bull Resources Inc., Halifax Hon. Jim Peterson Former federal cabinet minister, Counsel at Fasken DIRECTORS Martineau, Toronto Pierre Casgrain Maurice B. Tobin Director and Corporate Secretary of Casgrain the Tobin Foundation, Washington DC & Company Limited Erin Chutter President and CEO of Global Cobalt Corporation Research Advisory Board Laura Jones Janet Ajzenstat Executive Vice-President of the Canadian Federation Professor Emeritus of Politics, McMaster University of Independent Business (CFIB). Brian Ferguson Vaughn MacLellan Professor, Health Care Economics, University of Guelph DLA Piper (Canada) LLP Jack Granatstein Historian and former head of the Canadian War Museum Advisory Council Patrick James Professor, University of Southern California John Beck Rainer Knopff Chairman and CEO, Aecon Construction Ltd., Toronto Professor of Politics, University of Calgary Navjeet (Bob) Dhillon Larry Martin President and CEO, Mainstreet Equity Corp., Calgary Principal, Dr. -

The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: a History of Corporate Ownership in Canada

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: A History of Corporate Governance around the World: Family Business Groups to Professional Managers Volume Author/Editor: Randall K. Morck, editor Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-53680-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/morc05-1 Conference Date: June 21-22, 2003 Publication Date: November 2005 Title: The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Author: Randall Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Tian, Bernard Yeung URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10268 1 The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Randall K. Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Y. Tian, and Bernard Yeung 1.1 Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century, large pyramidal corporate groups, controlled by wealthy families or individuals, dominated Canada’s large corporate sector, as in modern continental European countries. Over several decades, a large stock market, high taxes on inherited income, a sound institutional environment, and capital account openness accompa- nied the rise of widely held firms. At mid-century, the Canadian large cor- porate sector was primarily freestanding widely held firms, as in the mod- ern large corporate sectors of the United States and United Kingdom. Then, in the last third of the century, a series of institutional changes took place. These included a more bank-based financial system, a sharp abate- Randall K. Morck is Stephen A. Jarislowsky Distinguished Professor of Finance at the University of Alberta School of Business and a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

Railway Background V3

BACKGROUND READING for “Irrational Exuberance:” The Creation of the CNR, 1917 – 1919 The Impact of Railways on the World MGT 2917 Canadian Business History Professor Joe Martin This reading was prepared by Professor Joe Martin to supplement the class discussion on The Creation of the CNR case. Copyright © 2005 by the Governing Council of the University of Toronto.To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials write to the Joseph L. Rotman School of Management, Business Information Centre,Toronto, M5S 3E6, or go to www.rotman.utoronto.ca/bic. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means, whether by photocopying, recording or by electronic or mechanical means, or otherwise, without the written permission of the Joseph L. Rotman School of Management. The Impact of Railways on the World Railroads first appeared in the United Kingdom in the early 19th Century.This new transportation technology turned out to be revolutionary in more than one sense. Railroads not only reduced travel time for individuals and dramatically cut the costs of shipped goods, they also contributed to the creation of modern capitalism and even led to the acceptance of standardized time. Simply put, the demands for capital were so great (“about $36,000 a mile on average at a time when $1,000 a year was a middle class income”)1 old ways of providing capital, usually from wholesale merchants, were no longer sufficient. As for the standardization of time, a uniquely Canadian contribution,2 railway travel spanning thousands of miles and several time zones (as was the case in Canada) required that time be synchronized on a more widespread standard basis, rather than varying from city to city, as had been the case prior to the adoption of Standard Time. -

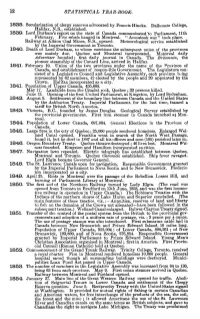

STATISTICAL YEAR-BOOK-. 1838. Secularization of Clergy Reserves

12 STATISTICAL YEAR-BOOK-. 1838. Secularization of clergy reserves advocated by Francis Hincks. Dalhousie College, Halifax, N.S., established. 1839. Lord Durham's report on the state of Canada communicated 'to Parliament, 11th February. Five rebels hanged in Montreal. " Aroostook war " took place. Railway at Albion Coal Mines, N.S., opened. Meteorological service established by the Imperial Government in Toronto. 1840. Death of Lord Durham, to whose exertions the subsequent union of the provinces was mainly due. Quebec and Montreal incorporated. Montreal daily Advertiser founded; first daily journal in Canada. The Britannia, the pioneer steamship of the Cunard Line, arrived in Halifax. 1841. February 10. Union of the two provinces under the name of the "Province of Canada, and establishment of responsible Government. The Legislature con sisted of a Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly, each province bfing represented by 62 members, 42 elected by the people and 20 appointed by the Crown. Halifax incorporated as a city. 1841. Population of Upper Canada, 455,688. May 17. Landslide from the Citadel rock, Quebec ; 32 persons killed. June 13. Opening of the first United Parliament, at Kingston, by Lord Sydenham. 1842. August 9. Settlement of the boundary line between Canada and the United States by the Ashburton Treaty. Imperial Parliament, for the last time, framed a tariff for British North America. 1843. Victoria, B.C., founded by James Douglas. Geological Survey established by the provincial government. First iron steamer in Canada launched a$ Mon treal. 1844. Population of Lower Canada, 697,084. General Elections in the Province of Canada. 1845. Large fires in the city of Quebec; 25,000 people rendered homeless. -

Grand Trunk Railway

History of the Grand Trunk Railway Local History at the St. Thomas Public Library 10 November 1852: The Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) is formally incorporated to construct a main railway line serving Ontario and Quebec, connecting Chicago with Portland, Maine. It is financed by a group of private British investors and fronted by Sir Francis Hincks, who is determined to build a main trunk line for eastern Canada. 1853: The Grand Trunk purchases five small railroad companies: the St. Lawrence & Atlantic (which reaches from Longueil, Quebec to Portland, Maine), Quebec & Richmond, Toronto & Guelph, Grand Junction, and Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada East. October 1856: The main line between Montreal and Toronto is opened. It is built with the Canadian Standard Gauge, 5’6”. December 1859: The Victoria Bridge is opened to traffic. It is a tubular bridge built originally for rail traffic, although lanes for automobiles will be added in 1927. It is the first bridge to span the St. Lawrence River, and is built especially for withstanding the ice and winter conditions of the river. The Victoria Bridge, Montreal, Quebec. 1859: An extension of the main line to Sarnia via Guelph, Stratford, and London is opened. The Grand Trunk Railway now provides through transportation from Sarnia to the Atlantic coast, a distance of 800 miles. 1860: The Grand Trunk acquires an extension from Quebec City to Rivière-du-Loup. 1861: The GTR has accumulated a debt of several hundred thousand pounds sterling as the result of expansion and overestimating the demand for rail service. Sir Edward William Watkin, railway chairman and politician, is sent from London to sort out the company’s financial situation. -

Ontario History Index from 1993 to 2016 Issue 1

Ontario History Scholarly Journal of The Ontario Historical Society since 1899 INDEX 1993-2016 Issue 1 The Ontario Historical Society Established in 1888, the OHS is a non-profit corporation and registered charity; a non-government group bringing together people of all ages, all walks of life and all cultural backgrounds interested in preserving some aspect of Ontario's history. Learn more at www.ontariohistoricalsociety.ca This index was made possible with the financial support of the Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport, the Honourable Michael Chan, Minister, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and the generous assistance of the Ontario Trillium Foundation. CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................... 3 Author Index ................................... 51 Books Reviewed Index .................... 112 Special Issues .................................. 160 Subject Index .................................. 172 To Go Back: Press ALT + (back arrow) (in downloaded PDF, not in browser) 2 Ontario History Scholarly Journal of The Ontario Historical Society since 1899 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1993-2016 Issue 1 The Ontario Historical Society Established in 1888, the OHS is a non-profit corporation and registered charity; a non-government group bringing together people of all ages, all walks of life and all cultural backgrounds interested in preserving some aspect of Ontario's history. Learn more at www.ontariohistoricalsociety.ca 3 To Go Back: Press ALT + (back arrow) (in downloaded PDF, not in browser) Go To Top (Contents) Ontario History, 1993-2016 Issue 1 Table of Contents Volume 85, 1: 1993 Editor: Jean Burnet 1. Cameron, Wendy, “’Till they get tidings from those who are gone…’ Thoms Sockett and Letters from Petworth Emigrants, 1832-1837.” 1-16 2. -

Canadian Government Policy Towards Titular Honours Fkom Macdondd to Bennett

Questions of Honoar: Canadian Government Policy Towards Titular Honours fkom Macdondd to Bennett by Christopher Pad McCreery A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Caaada September, 1999 Q Christopher Paul McCreery National birary Biblioth&quenationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliagraphiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaON KIAON4 OIEawaON K1AON4 Canada Cariada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde melicence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheqe nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or sell reproduire, preter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fih, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format ekctronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni Ia these ai des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent &re imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation- Abstract This thesis examines the Canadian government's policy towards British tituiar honours and their bestowal upon residents of Canada, c. 1867-1935. In the following thesis, I will employ primary documents to undertake an original study of the early development of government policy towards titular honours. The evolution and development of the Canadian government's policy will be examined in the context of increasing Canadian autonomy within the British Empire/Commonwealth- The incidents that prompted the development of a Canadian made formal policy will also be discussed. -

The Political History of Canada Between 1840 and 1855

IGtbranj KINGSTON. ONTARIO : 1 L THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF CUM BETWEEN 1840 AND 1855. A^ LECTURE DELIVERED ON THE 1 7th OCTOBER, 1877, AT THE REQUEST OP THE ST. PATRICK'S NATIONAL ASSOCIATION WITH COPIOUS ADDITIONS Hon. Sir FRANCIS HINCKS, P.C., K.C.M.G., C.B. JRontral DAWSON BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS. 1.877. «* ••••• ••••• •••«• • • • • • • • • • • I * • • • • • • • »•• • • • • « : THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF MAM BETWEEN 1840 AND 1855. A^ LECTURE DELIVERED ON THE 17th OCTOBER. 1877, AT THE REQUEST OF THE ST. PATRICK'S NATIONAL ASSOCIATION WITH COPIOUS ADDITIONS Hon. Sir FRANCIS HINCKS, P.C., K.C.M.G., C.B. Pontat DAWSON BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS. 1877. —A A desire having been expressed that the following lecture delivered on the 17th October, at the request of the St. Patrick's National Association—should be printed in pamphlet form, I have availed myself of the opportunity of elucidating some branches of the subjects treated of, by new matter, which could not have been introduced in the lecture, owing to its length. I have quoted largely from a pamphlet which I had printed in Jjondon in the year 1869, for private distribution, in consequence of frequent applications made to me, when the disestablishment of the Irish Church was under consideration in the House of Commons, for information as to the settlement of cognate ques- tions in Canada, and which was entitled w Religious Endowments in Canada: The Clergy Eeserve and Eectory Questions.— Chapter of Canadian History." The new matter in the pamphlet is enclosed within brackets, thus [ ]. F. HINCKS. Montreal, October, 1817. 77904 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/politicalhistoryOOhinc — The Political History of Canada. -

Developing Nova Scotia: Railways and Public Accounts, 1849-1867

ROSEMARIE LANGHOUT Developing Nova Scotia: Railways and Public Accounts, 1849-1867 SEVENTEEN YEARS AGO DEL MUISE argued that the view of history which cast Nova Scotians as uniformly and vehemently anti-Confederate needed revision.1 Pointing to the substantial group of voters in Nova Scotia who supported the Confederation option — with its implications of continental and industrial, rather than maritime and commercial growth — he suggested the existence of aspirations radically different from those commonly attributed to Maritimers of the Golden Age. Whereas traditional historical treatments of the wood, wind, and sail economy had presumed among Nova Scotians an affinity for a state structure which exercised only a limited jurisdiction, Muise's work made it clear that the option of an activist, interventionist state was not anathema to all colonial Nova Scotians. A revisionist interpretation of Maritime history has begun to appear-in the last decade, but much of this literature has been predom inantly concerned with the post-Confederation period. As a result, the origins of the developments Muise discussed have remained largely unexplored.2 In Nova Scotia the period of Responsible Government, from 1849 to 1867, was one of crucial importance in the development of public policy. As Nova Scotian politicians recognized, accepted and explored the control they could now exercise over the province's economic future, priorities shifted. Of central importance to this shift was a change in attitudes with respect to the role the state should play in society. Through much of the 19th century, political rhetoric, both in Britain and the colonies, supported cheap, limited government. -

Hincks, Sir Francis

HINCKS , Sir FRANCIS , banker, journalist, politician, and colonial administrator; b. 14 Dec. 1807 in Cork (Republic of Ireland), the youngest of nine children of the Reverend Thomas Dix Hincks and Anne Boult; m. first 29 July 1832 Martha Anne Stewart (d. 1874) of Legoniel, near Belfast (Northern Ireland), and they had five children; m. secondly 14 July 1875 Emily Louisa Delatre, widow of Robert Baldwin Sullivan*; d. 18 Aug. 1885 in Montreal, Que. Francis Hincks’s father was a Presbyterian clergyman whose interest in education and social reform led him to resign his pastorate and devote himself full time to teaching. His elder sons, of whom William* was one, became university teachers or clergymen, and it was assumed that Francis would follow in their footsteps. However, after briefly attending the Royal Belfast Academical Institution in 1823, he expressed a strong preference for a business career and was apprenticed to a Belfast shipping firm, John Martin and Company, in that year. In August 1832 Hincks and his bride of two weeks departed for York (Toronto), Upper Canada. He had visited the colony during the winter of 1830–31 while investigating business opportunities in the West Indies and the Canadas. Early in December he opened a wholesale dry goods, wine, and liquor warehouse in premises rented from William Warren Baldwin* and his son Robert*; the two families soon became close friends. Hincks’s first advertisement in the Colonial Advocate offered sherry, Spanish red wine, Holland Geneva (gin), Irish whiskey, dry goods, boots and shoes, and stationery to the general merchants of Upper Canada.