Guide to Best Practice Integrating Adaptation to Climate Change Into

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Sample Procurement Plan Agriculture and Land Growth Management Project (P151469) Public Disclosure Authorized I. General 2. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan: Original: January 2016 – Revision PP: December 2016 – February 2017 3. Date of General Procurement Notice: - 4. Period covered by this procurement plan: July 2016 to December 2017 II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: [Thresholds for applicable Public Disclosure Authorized procurement methods (not limited to the list below) will be determined by the Procurement Specialist /Procurement Accredited Staff based on the assessment of the implementing agency’s capacity.] Type de contrats Montant contrat Méthode de passation de Contrat soumis à revue a en US$ (seuil) marchés priori de la banque 1. Travaux ≥ 5.000.000 AOI Tous les contrats < 5.000.000 AON Selon PPM < 500.000 Consultation des Selon PPM fournisseurs Public Disclosure Authorized Tout montant Entente directe Tous les contrats 2. Fournitures ≥ 500.000 AOI Tous les contrats < 500.000 AON Selon PPM < 200.000 Consultation des Selon PPM fournisseurs Tout montant Entente directe Tous les contrats Tout montant Marchés passes auprès Tous les contrats d’institutions de l’organisation des Nations Unies Public Disclosure Authorized 2. Prequalification. Bidders for _Not applicable_ shall be prequalified in accordance with the provisions of paragraphs 2.9 and 2.10 of the Guidelines. July 9, 2010 3. Proposed Procedures for CDD Components (as per paragraph. 3.17 of the Guidelines: - 4. Reference to (if any) Project Operational/Procurement Manual: Manuel de procedures (execution – procedures administratives et financières – procedures de passation de marches): décembre 2016 – émis par l’Unite de Gestion du projet Casef (Croissance Agricole et Sécurisation Foncière) 5. -

Commune D'ambinanitelo 1967-1968

Repobli::u Mologosy Re publ ique Française OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE MINISTERE DES FINANCES ET DU COMMERCE ET TECHNIQUE OUTRE MER NSTITUT NATIONAL DE LA STATISTIQUt: Ire de Tananarive ET DE LA RÈCHERCHE ECONOMIQUE ENeE D'OBSERVATION PERMANENT DU MOUVE ENT DE LA POPUL ( Co une d' Ambinanitelo 19671968 ) F· GENDREAU 1969 UNE EXPERIENCE D'OBSERVATION PERMANENTE DU HOUVEMENT DE LA POPULATION (COl~ d'MJrnINAl~ITELO, 1967 - 1968) par Francis GEtIDREAU Chargé de Recherches à l'ORSTOM avec la collaboration de la Section Population de l'L~titut National de la Statistique et de la Recherche Economique. O.R.S.T.O.M. B.P. 434 Tananarive Tananarive, Août 1969. I.NoSoR.E. BoP. 485 Tananarive RESUME Ce rapport présente les résult1".ts d'une expérience d'"observation permanenteIl du mouvement de la population Denée durant un an dans la COWLlune Rurale d'Aobinanitelo, sur la Côte Est de Madagascar. Cette enquête avait essentielleBent pour objet de nettre au point une néthodologie adaptée aux besoins du pays'et de donner une preDière idée des causes et du degré de I:1é'.uvais fonctionneuent de l'Etat-Civil. Si ce genre d'opérati?ns se heurte à un certain nombre de difficultés provenant tant q.u Bilieu quo do If: l1LturO des phénonènes, cette expérience seuble ~ependant avoir Dis en évidence la richesse des :r:enseigneiJl(jnts qui peuvent en être tirés et l'intérêt que peut y trouver le. recherche dénographique. En effet la confrontation des évènenents enregistrés par l'Etat-Civil avec cetlX observés par l'enquêteur de l'observation pernanente pernet à l'ffilalyso des prolongoDonts et autorise des conclusions qui ne sont rendues possibles quo par l'existence de deux sources de renseigneoonts. -

17 Avril 2018

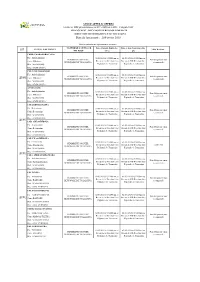

AVIS D’APPEL D’OFFRES N° 07 MRI-DIRA A toutes les MPE présélectionnées en 2017 -2018 par le FID FINANCEMENT: MECANISME DE REPONSE IMMEDIATE DIRECTION INTER REGIONALE DE TOAMASINA Date de lancement : 17 Avril 2018 Pour la réalisation des infrastructures suivantes : Date et lieu de dépôt des Date et lieu d’ouverture des INTITULE DE PROJET MAITRE DE L'OUVRAGE DELEGUE Visite des lieux LOT CAT offres plis EC TAMPOLO Fkt : TAMPOLO 02/05/2018 à 09 H 00 mn au 02/05/2018 à 09 H 30 mn au FID DIRECTION INTER REGIONALE Non Obligatoire mais Bureau de la Direction Inter Bureau de la Direction Inter Com : RANTABE DE TOAMASINA recommandée Régionale de Toamasina Régionale de Toamasina Dist : MAROANTSETRA Lot N°1 CAT 1 BAT Rég : ANALANJIROFO (Relance) EPP ANDROKAROKA Fkt : ANDROKAROKA 02/05/2018 à 09 H 00 mn au 02/05/2018 à 09 H 30 mn au FID DIRECTION INTER REGIONALE Non Obligatoire mais Com : MAROANTSETRA Bureau de la Direction Inter Bureau de la Direction Inter DE TOAMASINA recommandée Régionale de Toamasina Régionale de Toamasina Dist : MAROANTSETRA Rég : ANALANJIROFO CSB 1 SAHATELO Fkt : SAHATELO 02/05/2018 à 09 H 00 mn au 02/05/2018 à 09 H 30 mn au FID DIRECTION INTER REGIONALE Non Obligatoire mais Bureau de la Direction Inter Bureau de la Direction Inter Com : MASOMELOKA DE TOAMASINA recommandée Régionale de Toamasina Régionale de Toamasina Dist : MAHANORO Lot N°4 Rég : ATSINANANA CAT 1 BAT (Relance) CSB 1 AMBODIHARINA Fkt : AMBODIHARINA 02/05/2018 à 09 H 00 mn au 02/05/2018 à 09 H 30 mn au FID DIRECTION INTER REGIONALE Non Obligatoire mais Com : -

Candidats Fenerive Est Ambatoharanana 1

NOMBRE DISTRICT COMMUNE ENTITE NOM ET PRENOM(S) CANDIDATS CANDIDATS GROUPEMENT DE P.P MMM (Malagasy Miara FENERIVE EST AMBATOHARANANA 1 KOMPA Justin Miainga) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST AMBATOHARANANA 1 RAVELOSAONA Rasolo Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) GROUPEMENT DE P.P MMM (Malagasy Miara FENERIVE EST AMBODIMANGA II 1 SABOTSY Patrice Miainga) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST AMBODIMANGA II 1 RAZAFINDRAFARA Elyse Emmanuel Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) FENERIVE EST AMBODIMANGA II 1 INDEPENDANT TELO ADRIEN (Telo Adrien) TELO Adrien AMPASIMBE INDEPENDANT BOTOFASINA ANDRE (Botofasina FENERIVE EST 1 BOTOFASINA Andre MANANTSANTRANA Andre) AMPASIMBE GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST 1 VELONORO Gilbert MANANTSANTRANA Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) AMPASIMBE FENERIVE EST 1 GROUPEMENT DE P.P MTS (Malagasy Tonga Saina) ROBIA Maurille MANANTSANTRANA AMPASIMBE INDEPENDANT KOESAKA ROMAIN (Koesaka FENERIVE EST 1 KOESAKA Romain MANANTSANTRANA Romain) AMPASIMBE INDEPENDANT TALEVANA LAURENT GERVAIS FENERIVE EST 1 TALEVANA Laurent Gervais MANANTSANTRANA (Talevana Laurent Gervais) GROUPEMENT DE P.P MMM (Malagasy Miara FENERIVE EST AMPASINA MANINGORY 1 RABEFIARIVO Sabotsy Miainga) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST AMPASINA MANINGORY 1 CLOTAIRE Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) INDEPENDANT ROBERT MARCELIN (Robert FENERIVE EST ANTSIATSIAKA 1 ROBERT Marcelin Marcelin) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST ANTSIATSIAKA 1 KOANY Arthur Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) -

2 AON DIRA 200218.Xlsx

AVIS D’APPEL D’OFFRES A toutes les MPE présélectionnées en 2017 et 2018 par le FID : Catégorie 1BAT FINANCEMENT : MECANISME DE REPONSE IMMEDIATE DIRECTION INTER REGIONALE DE TOAMASINA Date de lancement : 20 Février 2018 Pour la réalisation des infrastructures suivantes : MAITRE DE L'OUVRAGE Date et lieu de dépôt des Date et lieu d’ouverture des INTITULE DE PROJET Visite des lieux LOT DELEGUE offres plis CHRD 2 MAHANORO Cuisine Fkt : Ambalakininina 02/03/2018 à 09 H 00 mn au 02 /03/2018 à 09 H 30mn au FID DIRECTION INTER Non Obligatoire mais Com : Mahanoro Bureau de la Direction Inter Bureau du FID Direction Inter REGIONALE DE TOAMASINA recommandée Dist : MAHANORO Régionale de Toamasina Régionale de Toamasina Rég : ATSINANANA CSB 2 SMI MAHANORO Fkt : Ambalakininina 02/03/2018 à 09 H 00 mn au 02 /03/2018 à 09 H 30mn au FID DIRECTION INTER Non Obligatoire mais Com : Mahanoro Bureau de la Direction Inter Bureau du FID Direction Inter LOT N°16 REGIONALE DE TOAMASINA recommandée Dist : MAHANORO Régionale de Toamasina Régionale de Toamasina Rég : ATSINANANA ANNEXE BSD Fkt : Ambalakininina 02/03/2018 à 09 H 00 mn au 02 /03/2018 à 09 H 30mn au FID DIRECTION INTER Non Obligatoire mais Com : Mahanoro Bureau de la Direction Inter Bureau du FID Direction Inter REGIONALE DE TOAMASINA recommandée Dist : MAHANORO Régionale de Toamasina Régionale de Toamasina Rég : ATSINANANA CSB 2 BETSIZARAINA Fkt : Betsizaraina 02/03/2018 à 09 H 00 mn au 02 /03/2018 à 09 H 30mn au FID DIRECTION INTER Non Obligatoire mais Com : Betsizaraina Bureau de la Direction Inter -

Sample Procurement Plan Agriculture and Land Growth Management Project (P151469)

Sample Procurement Plan Agriculture and Land Growth Management Project (P151469) Public Disclosure Authorized I. General 2. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan: Original: January 2016 – Revision PP: December 2016 – February 2017 3. Date of General Procurement Notice: - 4. Period covered by this procurement plan: July 2016 to December 2017 II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: [Thresholds for applicable Public Disclosure Authorized procurement methods (not limited to the list below) will be determined by the Procurement Specialist /Procurement Accredited Staff based on the assessment of the implementing agency’s capacity.] Type de contrats Montant contrat Méthode de passation de Contrat soumis à revue a en US$ (seuil) marchés priori de la banque 1. Travaux ≥ 5.000.000 AOI Tous les contrats < 5.000.000 AON Selon PPM < 500.000 Consultation des Selon PPM fournisseurs Public Disclosure Authorized Tout montant Entente directe Tous les contrats 2. Fournitures ≥ 500.000 AOI Tous les contrats < 500.000 AON Selon PPM < 200.000 Consultation des Selon PPM fournisseurs Tout montant Entente directe Tous les contrats Tout montant Marchés passes auprès Tous les contrats d’institutions de l’organisation des Nations Unies Public Disclosure Authorized 2. Prequalification. Bidders for _Not applicable_ shall be prequalified in accordance with the provisions of paragraphs 2.9 and 2.10 of the Guidelines. July 9, 2010 3. Proposed Procedures for CDD Components (as per paragraph. 3.17 of the Guidelines: - 4. Reference to (if any) Project Operational/Procurement Manual: Manuel de procedures (execution – procedures administratives et financières – procedures de passation de marches): décembre 2016 – émis par l’Unite de Gestion du projet Casef (Croissance Agricole et Sécurisation Foncière) 5. -

Madagascar Cyclone Enawo

Sambava Bealanana Andapa ! ! ! ! ! MA002_7 Marotolana Ambalavan!io ! Andapa Ambinanifaho Antsahameloka ! Antanandava Ambalaromba ! Bealampona ! Ampontsilahy ANOVIARA Manantenina Ambodiadabo M Andrakata Tsaratanana ! ! ! ! Ampah! ana Antsambalahy Marohasina Ambalambato ! ! Antetezantany Andilandrano ANTSAMBALAHY ! ! Maroambihy ! Ambodilalona ! ! ! Ankijanabe Andasibe Ambodivohitra Madiotsifafana ! ! ! Betavilona Ampondrabe ! Tanandava Anoviara (= Mahavelona) Andranofotsy Ambohinasondrotra Antanibe Manandriana Ambodimanga I ! Bemarambonga Ambohimarina ! ! ! ! ! Station Ambohimitsinjo ! Nosimbendrana ! ! Antsahabe ! Besariaka Antsirabe Ambodisikidy ! Ambodiadabo ! ! Antsahanoro! Andembilemisy SARAHANDRANO ! Ambohimarina ! Ambalapaiso ! ! Ambohitsara Sarahandrano Befontsy ! Ambahavala Betaindrafia Belalona ! ! ! Antananivo Marojao ! ! ! AMBINANY Andampy ANTSAHAMENA Antsahabeoran!a Amparihy ! (Androva) ! Matsondakana ! Antsahamena Ambalarivo Antsahamena ! ! Antanambaobe Antananambo ! Andampy Ankizanibe Andranobetsisilaoka ! Bemanevika ! Ambany ! Antombana S Ambodiangezoka ° ! 5 Andrikiriky 1 ! Ambohitsara MATSONDAKANA ! ! ! Ambendrana Analavory ! Marofototra ! Andranomena ! Lanjarivo Ambodisikidy ! ! Ambodisikidy ! Befandriana Marofinaritra Nord Ambinanitelo ! Manambolo Androfary Andranonahoatra ! ! Antsakabary Andaparaty ! ! Ambatonahisodrano ! Antalaha ! Ankarongana Antakotako Antsiradrano Andapanomby ! Manambolo Sakatihina ! ! Marovaka Ambohimena ! ! Sahajinja Ambatoharanana ! ! Marovovanana Tanambao Antakotako ! ! ! Rantavatobe-Andasibe -

Makira Forest Project Madagascar

Makira Forest Project Madagascar David Meyers December 18, 2001 MEF – IRG/PAGE – USAID Table of Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................................i I. Background .......................................................................................................... 1 II. The Makira Forest Project Overview..................................................................... 2 III. General Description of the Makira Forest Project Area......................................... 5 IV. The Carbon Value of Makira............................................................................... 12 A. Carbon Benefits of Makira................................................................................ 12 B. Leakage of Carbon Benefits............................................................................. 17 C. Carbon and Biodiversity................................................................................... 18 D. Financial Value of Makira Carbon .................................................................... 18 V. The Biodiversity Value of Makira ........................................................................ 20 A. Flora of Makira ................................................................................................. 21 B. Fauna of Makira ............................................................................................... 23 C. Biodiversity Conclusions ................................................................................. -

Total Population in Antalaha, Maroantsetra, Andapa and Sambava Districts

MA005 Anaborano Tsarabaria Ifasy Ambinanin'andravory 0 16,418 Andravory 11,276 Ambodimanga 4,616 Ampanefena Amboriala Ambodisambalahy 19,962 Ramena 9,800 Tanambao Manambato 12,649 10,418 Daoud Ambohitrandriana 5,237 9,106 5,358 Antananarivo Antsirabe Antsahavaribe Belambo Nord 13,390 7,632 40,146 Bevonotra Anjialava 7,716 Antindra Marotolana 12,653 16,706 11,734 Anjangoveratra Amboangibe 16,539 Ambatoafo 12,940 Marogaona Bemanevika Anjialavabe 10,453 6,813 10,447 6,621 Analamaho Nosiarina Andrembona 4,789 4,959 Mangindrano 4,930 Antananivo Anjinjaomby Sambava Cu 8,488 41,672 Haut Ambohimitsinjo 5,942 2,063 6,327 Ambohimalaza Ambovonomby Doany Andrahanjo Ambodivoara 8,208 Ambararatabe 7,364 15,569 0 9,703 Andratamarina Nord Morafeno 6,885 4,196 10,482 Farahalana Anjozoromadosy Ambodiampana 21,232 Analila 6,013 Maroambihy 11,530 Marojala 7,505 Ambalamanasy II 11,941 14,847 Bealanana 14,515 Marovato 18,603 Ambatoriha Antsambaharo Betsakotsako 4,787 Est Ankazotokana 3,593 Andranotsara Belaoka 12,737 3,978 7,472Andranomena Belaoka Lokoho Lanjarivo Ambodiangezoka 5,862 Ambinanifaho Marovato 5,828 14,813 26,294 10,451 Ambatosia Matsohely 5,662 12,796 Marotolana 5,841 Andapa Andrakata Ambodiadabo M Ankiakabe 8,133 Ambalaromba 21,952 6,750 7,851 Bealampona Nord Ambararata 5,271 13,425 7,478 Antsambalahy Ampahana Sofia 8,597 19,424 3,144 Anoviara Ambodimanga I 12,033 9,326 Tanandava 8,065 Antsahanoro Sarahandrano 12,446 Ambodisikidy 5,574 7,188 Antananambo Antalaha Ambonivohitra Matsondakana Antsahamena 13,423 Andampy 34,994 42,264 4,793 -

World Bank Document

Sample Procurement Plan Agriculture and Land Growth Management Project (P151469) Public Disclosure Authorized I. General 2. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan: Original: January 2016 – Revision PP: December 2016 – February 2017 3. Date of General Procurement Notice: - 4. Period covered by this procurement plan: July 2016 to December 2017 II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: [Thresholds for applicable Public Disclosure Authorized procurement methods (not limited to the list below) will be determined by the Procurement Specialist /Procurement Accredited Staff based on the assessment of the implementing agency’s capacity.] Type de contrats Montant contrat Méthode de passation de Contrat soumis à revue a en US$ (seuil) marchés priori de la banque 1. Travaux ≥ 5.000.000 AOI Tous les contrats < 5.000.000 AON Selon PPM < 500.000 Consultation des Selon PPM fournisseurs Public Disclosure Authorized Tout montant Entente directe Tous les contrats 2. Fournitures ≥ 500.000 AOI Tous les contrats < 500.000 AON Selon PPM < 200.000 Consultation des Selon PPM fournisseurs Tout montant Entente directe Tous les contrats Tout montant Marchés passes auprès Tous les contrats d’institutions de l’organisation des Nations Unies Public Disclosure Authorized 2. Prequalification. Bidders for _Not applicable_ shall be prequalified in accordance with the provisions of paragraphs 2.9 and 2.10 of the Guidelines. July 9, 2010 3. Proposed Procedures for CDD Components (as per paragraph. 3.17 of the Guidelines: - 4. Reference to (if any) Project Operational/Procurement Manual: Manuel de procedures (execution – procedures administratives et financières – procedures de passation de marches): décembre 2016 – émis par l’Unite de Gestion du projet Casef (Croissance Agricole et Sécurisation Foncière) 5. -

100 Dpi) 7 1:27000 5 5

356000 358000 360000 362000 364000 366000 368000 370000 372000 S 49°40'0"E 49°41'0"E 49°42'0"E 49°43'0"E 49°44'0"E 49°45'0"E 49°46'0"E 49°47'0"E 49°48'0"E 49°49'0"E " 0 ' 2 S 2 " ° 0 ' 5 2 1 GLIDE number: 2018-000023 Activation ID: EMSR274 2 ° 5 1 Product N.: 13MAROANTSETRA, v2, English MAROANTSETRA - MADAGASCAR 0 0 17 0 0 0 5 2 0 5 0 0 17 50 75 0 0 5 1 1 0 Storm - Situation as of 20/03/2018 0 12 5 0 5 00 0 3 2 3 8 8 Delineation Map 0 2 0 0 0 7 5 15 2 0 5 £ 2 £ 0 2 5 0 5 7 5 5 0 1 " 1 7 0 Mahajanga " 1 125 5 Antsiranana 5 2 5 1 0 S " 0 ' 3 S 2 " 5 20 ° 0 0 2 ' 2 5 5 0 3 2 0 1 2 ° 0 0 5 0 Mozambique 1 Maroantsetra 2 !13 1 0 ( 1 Channel 5 0 0 5 Anjahana Antananarivo 2 2 ^ 25 5 Madagascar 0 Toamasina INDIAN OCEAN 0 0 1 1 5 0 2 2 0 0 0 7 5 2 0 8 2 8 Antongila Bay 0 5 0 9 5 9 2 2 8 1 8 2 1 5 INDIAN OCEAN 2 2 Anjanazana 5 16 1 2 2 5 5 5 30 0 0 0 km 1 5 2 2 2 2 5 S 5 0 " 0 ' 5 4 S 2 " ° 0 7 ' 0 5 4 1 2 2 ° 0 2 5 1 1 2 Cartographic Information 5 0 1 0 1 1 2 Full color ISO A1, low resolution (100 dpi) 7 1:27000 5 5 5 0 0 7 2 2 5 0 0.5 1 2 5 5 1 25 0 km 150 0 0 0 5 0 0 Grid: W GS 1984 UTM Zone 39S map coordinate system 0 0 1 6 6 9 1 9 Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system 2 50 5 2 8 0 8 ± a Analanjirofo Toamasina an 5 l ba Legend 2 m na tai Crisis Information Hydrography Physiography n Flooded Area A 7 Coastline Elevation Contour (m) 5 S " (20/03/2018 07:22 UTC) 0 ' 5 S " Ankofa 2 River Tran£ sportation ° 0 General Information ' 5 5 1 2 Bridge and elevated highway ° Area of Interest Stream " 5 1 200 Placenames Island Secondary Road -

L'infrastructure Routière Face Au Développement

MINISTÈRE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEURE ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE ----------- ********************* ---------- FACULTÉ UNIVERSITÉDES LETTRES DE ET TOAMASINA SCIENCES HUMAINE, ---------- ---------- MENTION GÉOGRAPHIE MÉMOIRE EN VUE DE L’OBTENTION DU DIPLÔME DE MAÎTRISE EN GÉOGRAPHIE L’INFRASTRUCTURE ROUTIÈRE FACE AU DÉVELOPPEMENT ÉCONOMIQUE. CAS DU DISTRICT DE MAROANTSETRA DANS LARÉGION ANALANJIROFO Présentée par : Sulda RASOALANGE Sous la direction de : Monsieur Sylvestre TSIRAHAMBA, Maître de conférences à l’Université de Toamasina Année 2018 1 MINISTÈRE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEURE ET DE ----------- LA RECHERCHE ---------- SCIENTIFIQUE ********************* UNIVERSITÉ DE TOAMASINA FACULTÉ DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINE, ---------- ---------- MENTION GÉOGRAPHIE MÉMOIRE EN VUE DE L’OBTENTION DU DIPLÔME DE MAÎTRISE EN GÉOGRAPHIE L’INFRASTRUCTURE ROUTIÈRE FACE AU DÉVELOPPEMENT ÉCONOMIQUE. CAS DU DISTRICT DE MAROANTSETRA DANS LA RÉGION ANALANJIROFO MÉMOIRE POUR L’OBTENTION DE DIPLÔME DE MAITRISE EN GÉOGRAPHIE Présentée par : Sulda RASOALANGE Les membres du jury : Président : Monsieur JAORIZIKY, Professeur à l’Université de Toamasina Examinateur : Monsieur Maholy Félicien RABEMANAMBOLA, Maitre de conférences à l’Université de Toamasina Rapporteur : Monsieur Sylvestre TSIRAHAMBA, Maitre de conférences à l’université de Toamasina Année 2018 SOMMAIRE SOMMAIRE ............................................................................................................................... I REMERCIEMENTS ................................................................................................................