Benin: an African Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inadequacy of Benin's and Senegal's Education Systems to Local and Global Job Markets: Pathways Forward; Inputs of the Indian and Chinese Education Systems

Clark University Clark Digital Commons International Development, Community and Master’s Papers Environment (IDCE) 5-2016 INADEQUACY OF BENIN'S AND SENEGAL'S EDUCATION SYSTEMS TO LOCAL AND GLOBAL JOB MARKETS: PATHWAYS FORWARD; INPUTS OF THE INDIAN AND CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEMS. Kpedetin Mignanwande [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers Part of the Higher Education Commons, International and Comparative Education Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Mignanwande, Kpedetin, "INADEQUACY OF BENIN'S AND SENEGAL'S EDUCATION SYSTEMS TO LOCAL AND GLOBAL JOB MARKETS: PATHWAYS FORWARD; INPUTS OF THE INDIAN AND CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEMS." (2016). International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE). 24. https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers/24 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Master’s Papers at Clark Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE) by an authorized administrator of Clark Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. INADEQUACY OF BENIN'S AND SENEGAL'S EDUCATION SYSTEMS TO LOCAL AND GLOBAL JOB MARKETS: PATHWAYS FORWARD; INPUTS OF THE INDIAN AND CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEMS. Kpedetin S. Mignanwande May, 2016 A MASTER RESEARCH PAPER Submitted to the faculty of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, in partial fulfill- ment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in the department of International Development, Community, and Environment And accepted on the recommendation of Ellen E Foley, Ph.D. Chief Instructor, First Reader ABSTRACT INADEQUACY OF BENIN'S AND SENEGAL'S EDUCATION SYSTEMS TO LOCAL AND GLOBAL JOB MARKETS: PATHWAYS FORWARD; INPUTS OF THE INDIAN AND CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEMS. -

Benin Kingdom • Year 5

BENIN KINGDOM REACH OUT YEAR 5 name: class: Knowledge Organiser • Benin Kingdom • Year 5 Vocabulary Oba A king, or chief. Timeline of Events Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means 900 CE Lots of villages join together and make a “Rulers of the Sky”. kingdom known as Igodomigodo, ruled by Empire lots of countries or states, all ruled by the Ogiso. one monarch or single state. c. 900- A huge earthen moat was constructed Guild A group of people who all do the 1460 CE around the kingdom, stretching 16.000 km same job, usually a craft. long. Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 1180 CE The Oba royal family take over from the Voodoo The belief that non-human objects Osigo, and begin to rule the kingdom. (or Vodun) have spirits or souls. They are treated like Gods. Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as 1440 CE Benin expands its territory under the rule of Oba Ewuare the Great. a kind of money to trade with African leaders. 1470 CE Oba Ewuare renames the kingdom as Civil war A war between people who live in the Edo, with it;s main city known as Ubinu (Benin in Portuguese). same country. Moat A long trench dug around an area to 1485 CE The Portuguese visit Edo and Ubinu. keep invaders out. 1514 CE Oba Esigie sets up trading links with the Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Portuguese, and other European visitors. country by force, and live among the 1700 CE A series of civil wars within Benin lead to people. -

A Re-Assessment of Government and Political Institutions of Old Oyo Empire

QUAESTUS MULTIDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH JOURNAL A RE-ASSESSMENT OF GOVERNMENT AND POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS OF OLD OYO EMPIRE Oluwaseun Samuel OSADOLA, Oluwafunke Adeola ADELEYE Abstract: Oyo Empire was the most politically organized entity founded by the Yoruba speaking people in present-day Nigeria. The empire was well organized, influential and powerful. At a time it controlled the politics and commerce of the area known today as Southwestern Nigeria. It, however, serves as a paradigm for other sub-ethnic groups of Yoruba derivation which were directly or indirectly influenced by the Empire before the coming of the white man. To however understand the basis for the political structure of the current Yorubaland, there is the need to examine the foundational structure from which they all took after the old Oyo Empire. This paper examines the various political structures that made up government and governance in the Yoruba nation under the political control of the old Oyo Empire before the coming of the Europeans and the establishment of colonial administration in the 1900s. It derives its data from both primary and secondary sources with a detailed contextual analysis. Keywords: Old Oyo Empire INTRODUCTION Pre-colonial systems in Nigeria witnessed a lot of alterations at the advent of the British colonial masters. Several traditional rulers tried to protect and preserve the political organisation of their kingdoms or empires but later gave up after much pressure and the threat from the colonial masters. Colonialism had a significant impact on every pre- colonial system in Nigeria, even until today.1 The entire Yoruba country has never been thoroughly organized into one complete government in a modern sense. -

African Dialects

African Dialects • Adangme (Ghana ) • Afrikaans (Southern Africa ) • Akan: Asante (Ashanti) dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Fante dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Twi (Akwapem) dialect (Ghana ) • Amharic (Amarigna; Amarinya) (Ethiopia ) • Awing (Cameroon ) • Bakuba (Busoong, Kuba, Bushong) (Congo ) • Bambara (Mali; Senegal; Burkina ) • Bamoun (Cameroons ) • Bargu (Bariba) (Benin; Nigeria; Togo ) • Bassa (Gbasa) (Liberia ) • ici-Bemba (Wemba) (Congo; Zambia ) • Berba (Benin ) • Bihari: Mauritian Bhojpuri dialect - Latin Script (Mauritius ) • Bobo (Bwamou) (Burkina ) • Bulu (Boulou) (Cameroons ) • Chirpon-Lete-Anum (Cherepong; Guan) (Ghana ) • Ciokwe (Chokwe) (Angola; Congo ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Mauritian dialect (Mauritius ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Seychelles dialect (Kreol) (Seychelles ) • Dagbani (Dagbane; Dagomba) (Ghana; Togo ) • Diola (Jola) (Upper West Africa ) • Diola (Jola): Fogny (Jóola Fóoñi) dialect (The Gambia; Guinea; Senegal ) • Duala (Douala) (Cameroons ) • Dyula (Jula) (Burkina ) • Efik (Nigeria ) • Ekoi: Ejagham dialect (Cameroons; Nigeria ) • Ewe (Benin; Ghana; Togo ) • Ewe: Ge (Mina) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewe: Watyi (Ouatchi, Waci) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewondo (Cameroons ) • Fang (Equitorial Guinea ) • Fõ (Fon; Dahoméen) (Benin ) • Frafra (Ghana ) • Ful (Fula; Fulani; Fulfulde; Peul; Toucouleur) (West Africa ) • Ful: Torado dialect (Senegal ) • Gã: Accra dialect (Ghana; Togo ) • Gambai (Ngambai; Ngambaye) (Chad ) • olu-Ganda (Luganda) (Uganda ) • Gbaya (Baya) (Central African Republic; Cameroons; Congo ) • Gben (Ben) (Togo -

The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'ivoire, and Togo

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Public Disclosure Authorized Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon Public Disclosure Authorized 00000_CVR_English.indd 1 12/6/17 2:29 PM November 2017 The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 1 11/29/17 3:34 PM Photo Credits Cover page (top): © Georges Tadonki Cover page (center): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Cover page (bottom): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Page 1: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 7: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 15: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 32: © Dominic Chavez/World Bank Page 48: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 56: © Ami Vitale/World Bank 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 2 12/6/17 3:27 PM Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Nga Thi Viet Nguyen The team greatly benefited from the valuable and Felipe F. Dizon. Additional contributions were support and feedback of Félicien Accrombessy, made by Brian Blankespoor, Michael Norton, and Prosper R. Backiny-Yetna, Roy Katayama, Rose Irvin Rojas. Marina Tolchinsky provided valuable Mungai, and Kané Youssouf. The team also thanks research assistance. Administrative support by Erick Herman Abiassi, Kathleen Beegle, Benjamin Siele Shifferaw Ketema is gratefully acknowledged. Billard, Luc Christiaensen, Quy-Toan Do, Kristen Himelein, Johannes Hoogeveen, Aparajita Goyal, Overall guidance for this report was received from Jacques Morisset, Elisée Ouedraogo, and Ashesh Andrew L. Dabalen. Prasann for their discussion and comments. Joanne Gaskell, Ayah Mahgoub, and Aly Sanoh pro- vided detailed and careful peer review comments. -

Broadcast Media Intervention in Mental Health Challenge in Edo State, Nigeria

O. S. Omoera & P. Aihevba– Broadcast Media Intervention in Mental Health Challenge Medical Anthropology 439 - 452 Broadcast Media Intervention in Mental Health Challenge in Edo State, Nigeria Osakue Stevenson Omoera1 and Peter Aihevba2 Abstract In most communities, especially in Africa, people with mental health challenges are denigrated; the society is not sympathetic with sufferers of mental illness. A lot of issues can trigger mental illness. These can be stress (economic stress, social stress, educational stress, etc); hereditary factors; war and aggression; rape; spiritual factors, to mention a few. Therefore, there is the need for understanding and awareness creation among the people as one of the ways of addressing the problem. Methodologically, this study deploys analytical, observation and interview techniques. In doing this, it uses the Edo State, Nigeria scenario to critically reflect, albeit preliminarily, on the interventionist role the broadcast media have played/are playing/should play in creating awareness and providing support systems for mentally challenged persons in urban and rural centres in Nigeria. The study argues that television and radio media are very innovative and their innovativeness can be deployed in the area of putting mental health issue in the public discourse and calling for action. This is because, as modern means of mass communication, radio and television engender a technologically negotiated reaching-out or dissemination of information which naturally flows to all manner of persons regardless of -

The New Encyclopedia of Benin

Barbara Plankensteiner. Benin: Kings and Rituals. Gent: Snoeck, 2007. 535 pp. $85.00, cloth, ISBN 978-90-5349-626-8. Reviewed by Kate Ezra Published on H-AfrArts (December, 2008) Commissioned by Jean M. Borgatti (Clark Univeristy) The exhibition "Benin Kings and Rituals: This section of the catalog features 301 ob‐ Court Arts from Nigeria," organized by Barbara jects discussed in 205 entries by 19 authors. The Plankensteiner, is an extraordinary opportunity objects, all illustrated in full color, are drawn to see hundreds of masterworks of Benin art to‐ from twenty-five museums in Europe, the United gether in one place. It will be on view at the Art States, and Nigeria, and also include several Institute of Chicago, its only American venue, works privately owned by Oba Erediauwa and from July 10 to September 21, 2008. The colossal High Priest Osemwegie Ebohen of Benin City. exhibition catalog provides a permanent record Most of the international team of authors who of this remarkable exhibition and will soon be‐ wrote the catalog entries are renowned Benin come the essential reference work on Benin art, scholars; the others are Africanists who serve as culture, and history. The frst half of the book curators of collections that lent objects to the exhi‐ Benin Kings and Rituals: Court Arts from Nigeria, bition. A full half of the entries were written by edited by Barbara Plankensteiner, consists of Barbara Blackmun (forty-nine) , Kathy Curnow twenty-two essays by a world-class roster of schol‐ (twenty-six), Paula Ben-Amos Girshick (fourteen), ars on a broad range of topics and themes related and Joseph Nevadomsky (thirteen). -

West Africa Power Trade Outlook

--•--11TONY BLAIR ::=i! - ~ INSTITUTE POWER AID FOR GLOBAL FROMTHE AMERICAN PEOPLE ~-ii.!:!:CHANGE AFRICA ~1-, _•- A U.S. GOVERNMENT-LED PARTNERSHIP WEST AFRICA POWER TRADE OUTLOOK POWER AFRICA SENIOR ADVISORS GROUP PROGRAMME Cover Credit: USAID/PowerAfrica/Malawi 2 CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 11 2. Background And Purpose 19 2.1. Introduction 2.2. The Institute’s Energy Practice 2.3. Overview Of The Study 3. Regional Analysis 25 3.1. Approach To Modelling 3.2. Existing Trade 3.3. Two Strategic Priorities: Natural Gas And Power Trade 3.4. Natural Gas Availability And The West Africa Gas Pipeline 3.5. Regional Power Investments And Trading Opportunities 4. Recommendations 45 4.1 Foster Political Understanding And Leadership 4.2 Delivery Of “Transaction Centric” Action Plans To Increase Political Accountability 4.3 Provide Financial Backing For The Power Trades To Address Trust Issues And Accelerate The Market Development 4.4 Taking A Regional Approach To Gas Supplies 4.5 Creation Of A Transactions Oriented Delivery Unit 5. Appendix: The West Africa Gas Pipeline 47 6. Notes 49 3 4 PREFACE This Outlook was developed by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (TBI) in partnership with Power Africa in early 2018 through engagement with Governments, Utilities, the private sector and development partners throughout West Africa, as part of the Power Africa Senior Advisors Group programme.The projections presented in this Outlook are based on the most accurate inputs available at the time, and do not reflect subsequent developments. It would be prudent for this analysis to be updated at least every 2 to 3 years, and TBI is committed to sharing the analytical tools and approach used with regional institutions such that they can take this work forward. -

What Was Life Like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’S Enquiry: Why Is It Important to Learn About Benin in School?

History Our main enquiry question this term: What was life like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’s enquiry: Why is it important to learn about Benin in school? Benin Where is Benin? Benin is a region in Nigeria, West Africa. Benin was once a civilisation of cities and towns, powerful Kings and a large empire which traded over long distances. The Benin Empire 900-1897 Benin began in the 900s when the Edo people settled in the rainforests of West Africa. By the 1400s they had created a wealthy kingdom with a powerful ruler, known as the Oba. As their kingdom expanded they built walls and moats around Benin City which showed incredible town planning and architecture. What do you think of Benin City? Benin craftsmen were skilful in Bronze and Ivory and had strong religious beliefs. During this time, West Africa invented the smelting (heating and melting) of copper and zinc ores and the casting of Bronze. What do you think that this might mean? Why might this be important? What might this invention allowed them to do? This allowed them to produced beautiful works of art, particularly bronze sculptures, which they are famous for. Watch this video to learn more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zpvckqt/articles/z84fvcw 7 Benin was the center of trade. Europeans tried to trade with Benin in the 15 and 16 century, especially for spices like black pepper. When the Europeans arrived 8 Benin’s society was so advanced in what they produced compared with Britain at the time. -

Country Advice Nigeria Nigeria – NGA40366– Political Assassinations – People’S Democratic Party (PDP) – Passports 29 May 2012

Country Advice Nigeria Nigeria – NGA40366– Political Assassinations – People’s Democratic Party (PDP) – Passports 29 May 2012 1. Deleted. 2. Please provide general information relating to the Egor Local Government area in Benin City, including any information relating to political assassinations, other suspicious murders, corruption, connections to criminal gangs etc. The Local Government area of Egor is located within Edo State, in central-southern Nigeria. Its headquarters are in the town of Uselu, which according to Google Maps is approximately 10.2 kilometres from Benin City.1 The last census from 2006 estimated the population of the Egor Local Government area to be 339,899.2 It is noted that while Benin City does not fall within the Egor Local Government area3, given the areas proximity to the capital city many sources that discuss Egor Local Government area also make reference to Benin City. Figure 1: Map Showing Local Government Areas of Edo State, Nigeria4 Egor Local Government Area Uselu Benin City 1 Google Maps n.d., Uselu to Benin City <http://maps.google.com/maps?saddr=benin+city&daddr=Uselu,+Benin+City,+Nigeria&hl=en&ll=6.33236,5.62671 7&spn=0.275712,0.393791&sll=6.409056,5.614256&sspn=0.008615,0.012306&geocode=FQi6YAAdctpVACnxrM 95YtNAEDGg31hXwBCqhA%3BFWDLYQAdsKpVAA&mra=ls&t=m&z=12> Accessed 25 May 2012 2 Edo Heritage n.d., Egor <http://edoheritage.com/egor.html> Accessed 24 May 2012 3 Benin City falls within the Oredo Local Government area. 4 Nigerian Muse n.d., April 2007 Elections in Nigeria <http://www.nigerianmuse.com/20071205131228zg/nm- projects/electoral-reform-project/star-information-april-2007-elections-in-nigeria-the-case-of-edo-gubernatorial- elections/> Accessed 28 May 2012 Page 1 of 10 Reports were located of three political assassinations in Benin City in 2005 and 2000, two of which involved PDP members. -

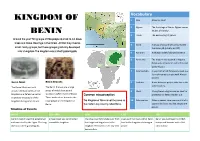

Kingdom of Benin Is Not the Same As 10 Colonisation When Invaders Take Over Control of a Benin

KINGDOM OF Vocabulary 1 Oba A king or chief. 2 Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means BENIN ‘Rulers of the Sky’. 3 Trade The exchanging of goods. Around the year 900 groups of Edo people started to cut down trees and make clearings in the forest. At first they lived in 4 Guild A group of people who all complete small family groups, but these groups gradually developed the same job (usually a craft). into a kingdom. The kingdom was called Igodomigodo. 5 Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 6 Benin city The modern city located in Nigeria. Previously, it has been called Edo and Igodomigodo. 7 Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as a form of money to trade with African leaders. Benin Moat Benin Bronzes 8 Civil war A war between people who live in the same country. The Benin Moat was built The Benin Bronzes are a large around the boundaries of the group of metal plaques and 9 Moat A long trench dug around an area for kingdom as a defensive barrier sculptures (often made of brass). Common misconception protection to keep invaders out. to protect the people of the These works of art decorate the kingdom during times of war. royal palace of the Kingdom of The Kingdom of Benin is not the same as 10 Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Benin. the modern day country called Benin. country by force, and live among the people. Timeline of Events 900 AD 900—1460 1180 1700 1897 Benin Kingdom was first established A huge moat was constructed The Oba royal family take over from A series of civil wars within Benin Benin was destroyed by British and was ruled by the Ogiso. -

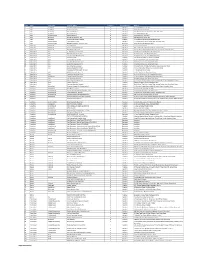

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State.