Grounding of Articulated Tug and Barge Nathan E Stewart/DBL 55

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

Commercial Fishing Guide

1981 Commercial Fishing Guide Includes: STOCK EXPECTATIONS and PROPOSED FISHING PLANS Government Gouvernement I+ of Canada du Canada Fisheries Pech es and Oceans et Oceans LIBRARY PACIFIC BIULUG!CAL STATION ADDENDUM 1981 Commercial Fishing Guide - Page 28 Two-Area Troll Licensing - clarification Fishermen electing for an inside licence will receive an inside trolling privilege only and will not be eligible to participate in any other salmon fishery on the coast. Fishermen electing for an outside licence may participate in any troll or net fishery on the coast except the troll fishery in the Strait of Georgia. , ....... c l l r t 1981 Commercial Fishing Guide Department of Fisheries and Oceans Pacific Region 1090 West Pender Street Vancouver, B.C. Government Gouvernement I+ of Canada du Canada Fisheries Pee hes and Oceans et Oceans \ ' Editor: Brenda Austin Management Plans Coordinator: Hank Scarth Cover: Bev Bowler Canada Joe Kambeitz 1981 Calendar JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH s M T w T F s s M T w T F s s M T w T F s 2 3 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 1-1 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 15 -16 17 18 19 20 21 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 ?2 23 _24 25 26 27 28 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 31 APRIL MAY JUNE s M T w T F s s M T w T F s s M T w T F s 1 2 3 4 1 2 2 3 4 5 6 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 -

RG 42 - Marine Branch

FINDING AID: 42-21 RECORD GROUP: RG 42 - Marine Branch SERIES: C-3 - Register of Wrecks and Casualties, Inland Waters DESCRIPTION: The finding aid is an incomplete list of Statement of Shipping Casualties Resulting in Total Loss. DATE: April 1998 LIST OF SHIPPING CASUALTIES RESULTING IN TOTAL LOSS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA COASTAL WATERS SINCE 1897 Port of Net Date Name of vessel Registry Register Nature of casualty O.N. Tonnage Place of casualty 18 9 7 Dec. - NAKUSP New Westminster, 831,83 Fire, B.C. Arrow Lake, B.C. 18 9 8 June ISKOOT Victoria, B.C. 356 Stranded, near Alaska July 1 MARQUIS OF DUFFERIN Vancouver, B.C. 629 Went to pieces while being towed, 4 miles off Carmanah Point, Vancouver Island, B.C. Sept.16 BARBARA BOSCOWITZ Victoria, B.C. 239 Stranded, Browning Island, Kitkatlah Inlet, B.C. Sept.27 PIONEER Victoria, B.C. 66 Missing, North Pacific Nov. 29 CITY OF AINSWORTH New Westminster, 193 Sprung a leak, B.C. Kootenay Lake, B.C. Nov. 29 STIRINE CHIEF Vancouver, B.C. Vessel parted her chains while being towed, Alaskan waters, North Pacific 18 9 9 Feb. 1 GREENWOOD Victoria, B.C. 89,77 Fire, laid up July 12 LOUISE Seaback, Wash. 167 Fire, Victoria Harbour, B.C. July 12 KATHLEEN Victoria, B.C. 590 Fire, Victoria Harbour, B.C. Sept.10 BON ACCORD New Westminster, 52 Fire, lying at wharf, B.C. New Westminster, B.C. Sept.10 GLADYS New Westminster, 211 Fire, lying at wharf, B.C. New Westminster, B.C. Sept.10 EDGAR New Westminster, 114 Fire, lying at wharf, B.C. -

The Nathan E. Stewart and Its Oil Spill MARCH 2017 HEILTSUK NATION PHOTO: APRIL BENCZE

PHOTO: KYLE ARTELLE PHOTO: KYLE HEILTSUK TRIBAL COUNCIL INVESTIGATION REPORT: The 48 hours after the grounding of the Nathan E. Stewart and its oil spill MARCH 2017 HEILTSUK NATION PHOTO: APRIL BENCZE A life ring from the Nathan E. Stewart floating in sheen of diesel oil. **Details regarding the photographs contained in this report are contained in the Schedule of Photographs located at the end of this document. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GLOSSARY 4 6.0 HEILTSUK NATION’S POSITION 31 1.1. GLOSSARY OF ORGANIZATIONS 4 ON OIL TANKERS 1.2. GLOSSARY OF VESSELS 4 6.1. MARINE USE PLAN 31 1.3. LIST OF SCHEDULES 5 6.2. SUPPORT FOR A TANKER 31 MORATORIUM 2.0 HEILTSUK NATION JURISDICTION 7 6.3. ENBRIDGE NORTHERN GATEWAY 31 PIPELINE PROJECT 3.0 INVESTIGATION 9 3.1. DOCUMENTS 9 7.0 GALE PASS AND SEAFORTH 32 3.1.1. Requests 9 CHANNEL 3.1.2. Limited Access to 16 7.1. LOCATION OF INCIDENT 32 IAP Software 7.2. CHIEFTAINSHIP OF AREA 33 3.2. INTERVIEWS 16 3.2.1. Requests 16 8.0 EVENTS OF OCTOBER 13, 2016 36 3.2.2. Witnesses 16 (DAY 1) 8.1. CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS 36 4.0 NATHAN E. STEWART AND DBL-55 17 8.2. SPECIFIC ISSUES 42 4.1. KIRBY CORPORATION 17 4.1.1. Tug and Barge Business 17 9.0 EVENTS OF OCTOBER 14, 2016 44 4.1.2. Oil Spill History 18 (DAY 2) 4.2. NATHAN E. STEWART AND DBL-55 20 9.1. CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS 44 4.2.1. -

Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences #### 2009 CERTIFICATION UNIT PROFILE: NORTH COAST and CENTRAL COAST

Submitted to the Marine Stewardship Council on June 1, 2009. The Manuscript Report will be available through DFO’s library website at http://inter01.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/waves2/index.html Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences #### 2009 CERTIFICATION UNIT PROFILE: NORTH COAST AND CENTRAL COAST CHUM SALMON by B. Spilsted and G. Pestal1 Fisheries & Aquaculture Management Branch Department of Fisheries and Oceans 200 - 401 Burrard St Vancouver, BC V6C 3S4 1SOLV Consulting Ltd., Vancouver, BC V6H 4B9 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2009. Cat. No. Fs 97-4/2855E-PDF ISSN 1488-5387 Correct citation for this publication: Spilsted, S. and G. Pestal. 2009. Certification Unit Profile: North Coast and Central Coast Chum Salmon. Can. Man. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. ####: vii + 65p. Table of Contents Abstract .........................................................................................................................................vi Résumé ..........................................................................................................................................vi Preface ..........................................................................................................................................vii 1 Introduction............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Stocks covered in this document ................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Fisheries covered -

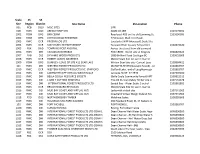

Scale Site SS Region SS District Site Name SS Location Phone

Scale SS SS Site Region District Site Name SS Location Phone 001 RCB DQU MISC SITES SIFR 01B RWC DQC ABFAM TEMP SITE SAME AS 1BB 2505574201 1001 ROM DPG BKB CEDAR Road past 4G3 on the old Lamming Ce 2505690096 1002 ROM DPG JOHN DUNCAN RESIDENCE 7750 Lower Mud river Road. 1003 RWC DCR PROBYN LOG LTD. Located at WFP Menzies#1 Scale Site 1004 RWC DCR MATCHLEE LTD PARTNERSHIP Tsowwin River estuary Tahsis Inlet 2502872120 1005 RSK DND TOMPKINS POST AND RAIL Across the street from old corwood 1006 RWC DNI CANADIAN OVERSEAS FOG CREEK - North side of King Isla 6046820425 1007 RKB DSE DYNAMIC WOOD PRODUCTS 1839 Brilliant Road Castlegar BC 2503653669 1008 RWC DCR ROBERT (ANDY) ANDERSEN Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1009 ROM DPG DUNKLEY- LEASE OF SITE 411 BEAR LAKE Winton Bear lake site- Current Leas 2509984421 101 RWC DNI WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. MAHATTA RIVER (Quatsino Sound) - Lo 2502863767 1010 RWC DCR WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. STAFFORD Stafford Lake , end of Loughborough 2502863767 1011 RWC DSI LADYSMITH WFP VIRTUAL WEIGH SCALE Latitude 48 59' 57.79"N 2507204200 1012 RWC DNI BELLA COOLA RESOURCE SOCIETY (Bella Coola Community Forest) VIRT 2509822515 1013 RWC DSI L AND Y CUTTING EDGE MILL The old Duncan Valley Timber site o 2507151678 1014 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD Sandal Bay - Water Scale. 2 out of 2502861881 1015 RWC DCR BRUCE EDWARD REYNOLDS Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1016 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Ladysmith virtual site 2507541962 1017 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Coastland Virtual Weigh Scale at Mu 2507541962 1018 RTO DOS NORTH ENDERBY TIMBER Malakwa Scales 2508389668 1019 RWC DSI HAULBACK MILLYARD GALIANO 200 Haulback Road, DL 14 Galiano Is 102 RWC DNI PORT MCNEILL PORT MCNEILL 2502863767 1020 RWC DSI KURUCZ ROVING Roving, Port Alberni area 1021 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD-DEAN 1 Dean Channel Heli Water Scale. -

Download the 2019-2020 Annual Report

SHIP-SOURCE OIL POLLUTION FUND SOPF CIDPHN 30 YEARS The Administrator’s Annual Report 2019-2020 Cover Image: Cormorant Kathryn Spirit (“Capsized Ship - Beauharnois – Canada”/Shutterstock.com) Pitts Carillon (Canadian Coast Guard) Published by the Administrator of the Ship-source Oil Pollution Fund Suite 830, 180 Kent Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0N5 Tel.: (613) 991-1726 Fax: (613) 990-5423 http://www.sopf.gc.ca The Honourable Marc Garneau, P.C., M.P. Minister of Transport Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0N5 Dear Minister: Pursuant to Section 121 of the Marine Liability Act, I have the honour of presenting to you the Annual Report for the Ship-source Oil Pollution Fund to be laid before each House of Parliament. The report covers the fiscal year ending March 31, 2020. Yours sincerely, Anne Legars, LL.M., CAE Administrator of the Ship-source Oil Pollution Fund TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................3 1. ACTIVITY REPORT.................................................................................................................................................4 1.1. Claims and Incident Reports for Canadian Oil Spill Incidents.............................................................................6 Map of the Fund’s active portfolio in 2019-2020 ...................................................................................................8 1.1.1. 2019-2020 Claims Portfolio Overview .............................................................................................................10 -

Sea & Shore Technical Newsletter N°44

1 CENTRE OF DOCUMENTATION, RESEARCH AND EXPERIMENTATION ON ACCIDENTAL WATER POLLUTION 715, Rue Alain Colas, CS 41836 - 29218 BREST CEDEX 2, FRANCE Tel: +33 (0)2 98 33 10 10 – Fax: (33) 02 98 44 91 38 Email: [email protected] - Website: www.cedre.fr Sea & Shore Technical Newsletter n°44 Contents • Spills ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Gulf of Mexico: repeated spills in the mouth of the Mississippi (US) ................................................................ 2 Non-persistent pollution due to rig grounding (Transocean Winner, Scotland) ................................................. 3 Potential transboundary pollution from an oil terminal (Aqaba, Jordan) ........................................................... 4 Heavy fuel oil spill in a port from a bunker vessel: small spill but significant impact (Trident Star, Malaysia) ... 4 Oil tanker fires and pollution in North America (Burgos, Mexico; Aframax River, USA).................................... 5 Offshore non-persistent oil spill (Clair rig, North Sea, Scotland) ....................................................................... 5 Diesel spill: medium-sized spill, high sensitivities (Nathan E. Stewart, Canada) .............................................. 5 • Past spills ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Houston Ship Channel spill: fines and safety -

Littleneck Clams

Scientific Excellence • Resource Protection & Conservation • Benefits for Canadians Excellence scientifique • Protection et conservation des ressources • Benefices aux Canadiens Intertidal Clam Surveys of British Columbia - 1991 • N. F. Bourne, G. D. Heritage, and G. Cawdell ~} ~~ "" I. Biological Sciences Branch ". ' ' . Department of Fisheries and Oceans Pacific Biological Station Nanaimo, British Columbia V9R 5K6 1994 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 1972 Fisheries Peches 1+1 and Oceans et Oceans Canada Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Technical reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which is not normally appropriate for primary literature. Technical reports are directed primarily toward a worldwide audience and have an international distribution. No restriction is placed on subject matter and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Technical reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts and indexed in the Department's annual index to scientific and technical publications. Numbers 1-456 in this series were issued as Technical Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 457-714 were issued as Department of the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service, Research and Development Directorate Technical Reports. Numbers 715-924 were issued as Department of Fisheries and the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Technical Reports. The current series name was changed with report number 925. Technical reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. Requests for individual reports will be filled by the issuing establishment listed on the front cover and title page. -

DRAFT Northern Salmon IFMP 2020-21

PACIFIC REGION DRAFT INTEGRATED FISHERIES MANAGEMENT PLAN JUNE 1, 2020 - MAY 31, 2021 SALMON NORTHERN BC Genus Oncorhynchus This Integrated Fisheries Management Plan is intended for general purposes only. Where there is a discrepancy between the Plan and the Fisheries Act and Regulations, the Act and Regulations are the final authority. A description of Areas and Subareas referenced in this Plan can be found in the Pacific Fishery Management Area Regulations, 2007. TABLE OF CONTENTS DEPARTMENT CONTACTS ..................................................................................................... 12 INDEX OF WEB-BASED INFORMATION ............................................................................... 15 GLOSSARY AND LIST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................. 21 FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................ 24 NEW FOR 2020/2021 .................................................................................................................... 25 1 OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................... 28 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 28 1.2 History .................................................................................................................................... 28 1.3 Type of -

COMMERCIAL FISHING GUIDE Proposed Fisliing Plans and Stock Expectations

DFO • Library I MPO • BibliotMque 1982 l l ll l ll ll ~ij~ ~~,~~Hl ll l COMMERCIAL FISHING GUIDE Proposed Fisliing Plans and Stock Expectations SH 22 4 P2 A93 1982 1982 Commercial Fishing Guide Editor: Brenda Austin Department of Fisheries and Oceans Pacific Region 1090 West Pender Street Vancouver, B.C. V6E 2Pl Government Gouvernement I+ of Canada du Canada Fisheries Pee hes and Oceans et Oceans GULF REGIONAL LIBRAR't ~ FISHERIES AND OCEANS \..__,.: ·~ BIBLIOT I QUE REGION DU GO[~ PECHE T OCEANS .;; ~ -~ 1982 Calendar JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH s M T W T F S S M T W T F s s M T W T F s 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 28 29 30 31 31 APRIL MAY JUNE S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 2 3 1 1 2 3 4 5 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 25 26 27 28 29 30 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 27 28 29 30 30 31 JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 26 27 28 29 30 31 31 3 This publication is based on the best available information at the time of printing and is intended as a guideline only. -

FLATS BOATS UPDITE the Magic Hours

Special Reporfp y Dusk and Dawn — FLATS BOATS UPDITE The Magic Hours Exploring -the/British Columbia Coast inside septembei/oclobei Features 30 Madness at Marthas Vineyard BY NELSON SIGELMAN Fishing in the fast lane 40 A British Columbia Coastal Odyssey BY JACK BERRYMAN Exploring for salmon and rockfish 50 Surfing for Snook BY BILL MURDICH How and where to hook a snook On the cover.. Fly tying on the Inside Passage. Photo by BRIAN O'KEEFE Departments 0 Publisher's Letter Bycatch—euphemism for plunder 0 Mailboat Readers ponder history and a bait ban 14 Salt Spray Conservation matters and other stuff 22 Resource Grass comes back to Galveston Bay 30 Fly Tier's Bench Dan Blanton's Sar-Mul-Mac 33 New Titles Casting, coastal fishing and billfish 10 Boating: Special Report What's new in flats boats 19 New Products 11 Q&A with Lefty Kreh Orvis launches Trident; marine products, and more Questions about lines and leaders One More Cast 70 Fly Casting Instructors Watcli for the iovember/Qecember issue SPINDHF," BY CHALLENGER ol Fly Fisliinj in Salt Waters, lealuring: Texas Specs • Mangrove Snappers * Imitating East Coast Baitfish All About Backing • Cuban Preview • Ten Thousand Islands 0 cycled pape; Budget Fishing • The Net Ban Spreads. FLY FISHING IN SALT WATERS Written by Jack' W. Hcvryman Ok , so maybe salmon on a cast fly the British Columbia and was optimistic we coast doesn't rank at could do the same. the top of the list of Shearwater is located the world's favorite on Denny Island near saltwater fly-fishing the famous Inside spots.