Eliminating the Mere Exposure Effect Through Changes in Context Between Exposure and Test Daniel De Zilva a , Chris J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exposure and Vulnerability

Determinants of Risk: 2 Exposure and Vulnerability Coordinating Lead Authors: Omar-Dario Cardona (Colombia), Maarten K. van Aalst (Netherlands) Lead Authors: Jörn Birkmann (Germany), Maureen Fordham (UK), Glenn McGregor (New Zealand), Rosa Perez (Philippines), Roger S. Pulwarty (USA), E. Lisa F. Schipper (Sweden), Bach Tan Sinh (Vietnam) Review Editors: Henri Décamps (France), Mark Keim (USA) Contributing Authors: Ian Davis (UK), Kristie L. Ebi (USA), Allan Lavell (Costa Rica), Reinhard Mechler (Germany), Virginia Murray (UK), Mark Pelling (UK), Jürgen Pohl (Germany), Anthony-Oliver Smith (USA), Frank Thomalla (Australia) This chapter should be cited as: Cardona, O.D., M.K. van Aalst, J. Birkmann, M. Fordham, G. McGregor, R. Perez, R.S. Pulwarty, E.L.F. Schipper, and B.T. Sinh, 2012: Determinants of risk: exposure and vulnerability. In: Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation [Field, C.B., V. Barros, T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, D.J. Dokken, K.L. Ebi, M.D. Mastrandrea, K.J. Mach, G.-K. Plattner, S.K. Allen, M. Tignor, and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA, pp. 65-108. 65 Determinants of Risk: Exposure and Vulnerability Chapter 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................67 2.1. Introduction and Scope..............................................................................................................69 -

124214015 Full.Pdf

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI DEFENSE MECHANISM ADOPTED BY THE PROTAGONISTS AGAINST THE TERROR OF DEATH IN K.A APPLEGATE’S ANIMORPHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MIKAEL ARI WIBISONO Student Number: 124214015 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2016 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI DEFENSE MECHANISM ADOPTED BY THE PROTAGONISTS AGAINST THE TERROR OF DEATH IN K.A APPLEGATE’S ANIMORPHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MIKAEL ARI WIBISONO Student Number: 124214015 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2016 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI A SarjanaSastra Undergraduate Thesis DEFENSE MECIIAMSM ADOPTED BY TITE AGAINST PROTAGOMSTS THE TERROR OT OTATTT IN K.A APPLEGATE'S AAUMORPHS By Mikael Ari Wibisono Student Number: lz4ll4}ls Defended before the Board of Examiners On August 25,2A16 and Declared Acceptable BOARD OF EXAMINERS Name Chairperson Dr. F.X. Siswadi, M.A. Secretary Dra. Sri Mulyani, M.A., ph.D / Member I Dr. F.X. Siswadi, M.A. Member2 Drs. HirmawanW[ianarkq M.Hum. Member 3 Elisa DwiWardani, S.S., M.Hum Yogyakarta, August 31 z}rc Faculty of Letters fr'.arrr s41 Dharma University s" -_# 1,ffi QG*l(tls srst*\. \ tQrtnR<{l -

Novel Learning-Based Spatial Reuse Optimization in Dense WLAN Deployments Imad Jamil1,3*, Laurent Cariou2 and Jean-François Hélard3

Jamil et al. EURASIP Journal on Wireless Communications and Networking (2016) 2016:184 DOI 10.1186/s13638-016-0632-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Novel learning-based spatial reuse optimization in dense WLAN deployments Imad Jamil1,3*, Laurent Cariou2 and Jean-François Hélard3 Abstract To satisfy the increasing demand for wireless systems capacity, the industry is dramatically increasing the density of the deployed networks. Like other wireless technologies, Wi-Fi is following this trend, particularly because of its increasing popularity. In parallel, Wi-Fi is being deployed for new use cases that are atypically far from the context of its first introduction as an Ethernet network replacement. In fact, the conventional operation of Wi-Fi networks is not likely to be ready for these super dense environments and new challenging scenarios. For that reason, the high efficiency wireless local area network (HEW) study group (SG) was formed in May 2013 within the IEEE 802.11 working group (WG). The intents are to improve the “real world” Wi-Fi performance especially in dense deployments. In this context, this work proposes a new centralized solution to jointly adapt the transmission power and the physical carrier sensing based on artificial neural networks. The major intent of the proposed solution is to resolve the fairness issues while enhancing the spatial reuse in dense Wi-Fi environments. This work is the first to use artificial neural networks to improve spatial reuse in dense WLAN environments. For the evaluation of this proposal, the new designed algorithm is implemented in OPNET modeler. Relevant scenarios are simulated to assess the efficiency of the proposal in terms of addressing starvation issues caused by hidden and exposed node problems. -

SOURCE MERE EXPOSURE and PERSUASION a Dissertation

SOURCE MERE EXPOSURE AND PERSUASION A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Ian M. Handley August 2003 This dissertation entitled SOURCE MERE EXPOSURE AND PERSUASION BY IAN M. HANDLEY has been approved for the Department of Psychology and the College of Arts and Sciences by G. Daniel Lassiter Professor of Psychology Leslie A. Flemming Dean, College of Arts and Sciences HANDLEY, IAN M. Ph.D. August 2003. Psychology Source Mere Exposure and Persuasion (146 pp.) Director of Dissertation: G. Daniel Lassiter Recent research on the “mere exposure effect” has demonstrated that repeated exposure to a stimulus induces diffuse positive affect—the source or target of which individuals are unaware—capable of positively influencing individuals’ preferences for that stimulus, similar stimuli, and quite novel stimuli. In this dissertation, four studies have tested the notion that repeated exposure to the source (communicator) of a persuasive communication similarly induces diffuse positive affect that, ultimately, favorably influences individuals’ attitudes toward that communication. In Study 1, participants were initially presented a female face. Later, half of the participants were shown the same face, and another half were shown a novel face, as being the author of an upcoming essay. All participants then read a persuasive essay and indicated their attitudes toward the essay, thoughts about the essay, and liking for the author. Results indicated that participants who had been repeatedly exposed to the essay author, relative to those who had not, formed more favorable attitudes and generated more favorable thoughts about the essay. -

A National Profile of Children Exposed to Family Violence: Police Response, Family Response, & Individual Impact

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: A National Profile of Children Exposed to Family Violence: Police Response, Family Response, & Individual Impact Author(s): David Finkelhor, Heather Turner Document No.: 248577 Date Received: January 2015 Award Number: 2010-IJ-CX-0021 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. NIJ 2010-IJ-CX-0021 Final Report 1 December 16, 2014 A National Profile of Children Exposed to Family Violence: Police Response, Family Response, & Individual Impact David Finkelhor Heather Turner Crimes against Children Research Center University of New Hampshire 125 McConnell Hall 15 Academic Way Durham, NH 03824 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. NIJ 2010-IJ-CX-0021 Final Report 2 Abstract A National Profile of Children Exposed to Family Violence: Police Response, Family Response and Individual Impact provides the first nationally representative data on youth contact with law enforcement and victim services – including best practices and help-seeking obstacles – for cases of family violence involving exposure to children. -

Study of Response of Human Beings Accidentally Exposed to Significant Fallout Radiation

.._... —____ ... _.. - ‘---- ( --- . c Jk!-t 1+. “’?mlts,w OPERAIION CASTLE - ~lNAL REPORT PRO Jt(’1 4 1“ ~ * Study of Response of Human Beings Accidentally Exposed to Significant Fallout Radiation ,. by !--- E. P. Cronkite, Commander, MC, USN .. V. P. Bond, M. D., Ph.D. L. F,. Browning, Lt. Col., MC, USA W. H. Chapman, Lt., MSC, USN .- . S. H. Cohn, Ph.D. ft. A. Conard, Commander, MC, USN .+$$$ ,#Je C. L. Dunham, M.D. 1?. S. Farr, Lt., MC, USN W. S. Hall, Conlm:mder, MC, USN ,,,:$gl~$ti it. Sharp, Lt. (jg), USN N. R. Shulman, L~., MC, USN <~“:’’~,~ \ ~.;L ,).’ , !,3$ ,@ ,\ +“’.:: ! ()t,ltb(, r 1954 ;. g . .. ‘. ,,<f\~ :W ,). +! NIIVUIMcdicwl 1{{.search III. IIUI(, ~.. Iltth(si;,,Marvl:n,lS3~;’~&$ “‘“ ““ }Ind ‘\ 11.S. Naval Rad]olo~mal Defense Lubo&‘ .V San i~’rant isco, California ,; ,. .- -.——.—— .. .. -4 ., L. ,. -k -w ABSTRACT . F(Jll(JwIIIg tli(, cf(, donation” of Shot 1 I)n Ilikini Atoll (m 1 Mar(mh 1!)54, 28 Ali)(,]-i(-;ttt*”i\l]ct 239 M~rsllill 1(,s(, W(Sr(J(,x]J(~s(,d to fill lout. One hull(irtd fifty -SCW(,II(I[ th(} Mitrsll:Ill(,s(~ wi~r{ 011 U(Irik /ltoli, M WI,I.(, III) 1{1111~{,l;Il) Aloll, ;Lll(i 18 w(.rt~ (III th(, 1]~.i~hl)orll]g :11011of .Alllll~litilt~. TII(J 2X An)(,rl(:ll]~ w(,I( I)n l{(,!l~!(,rlk Atoll. TII(s l)rI.s(*I\r(I of SIKIIIII(.;IIII fiillo~lt 011tli(~st, i~l(]ll~ was flrsi lll.l(r II IIIII.11 I)v :1 r{>(.{)1.{lltig(h)sil])(4(,r, 1()(’;l[td 011 lton~t, rik, Wh(~[l thls (t(Wl(. -

Biological Effects of Radiation Biological Effects of Radiation

Reactor Concepts Manual Biological Effects of Radiation Biological Effects of Radiation Whether the source of radiation is natural or man-made, whether it is a small dose of radiation or a large dose, there will be some biological effects. This chapter summarizes the short and long term consequences which may result from exposure to radiation. USNRC Technical Training Center 9-1 0603 Reactor Concepts Manual Biological Effects of Radiation Radiation Causes Ionizations of: ATOMS which may affect MOLECULES which may affect CELLS which may affect TISSUES which may affect ORGANS which may affect THE WHOLE BODY Although we tend to think of biological effects in terms of the effect of radiation on living cells, in actuality, ionizing radiation, by definition, interacts only with atoms by a process called ionization. Thus, all biological damage effects begin with the consequence of radiation interactions with the atoms forming the cells. As a result, radiation effects on humans proceed from the lowest to the highest levels as noted in the above list. USNRC Technical Training Center 9-2 0603 Reactor Concepts Manual Biological Effects of Radiation CELLULAR DAMAGE Even though all subsequent biological effects can be traced back to the interaction of radiation with atoms, there are two mechanisms by which radiation ultimately affects cells. These two mechanisms are commonly called direct and indirect effects. USNRC Technical Training Center 9-3 0603 Reactor Concepts Manual Biological Effects of Radiation Direct Effect Damage To DNA From Ionization If radiation interacts with the atoms of the DNA molecule, or some other cellular component critical to the survival of the cell, it is referred to as a direct effect. -

Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management Plan, June 2019

OREGON WOLF CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT PLAN OREGON DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE JUNE 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY June 2019 The Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management Plan (Plan) was first adopted in 2005 and updated in 2010. This update, which began in March 2016, is the result of a thorough, multi-year evaluation of the Plan and included a facilitated stakeholder process. Some of the changes contained within this Plan are general updates and reorganization of content. Other changes are more substantive in nature, and include management improvements based on information gained over years of wolf management in Oregon. In general, changes made in this Plan include: 1) updates to base information (i.e., status, population, distribution, etc.), 2) new science related to the biology and management of wolves, and 3) management improvements based on information gained through years of wolf management in Oregon. Chapter II (Wolf Conservation and Monitoring) includes detailed information on the three phases of wolf management and discusses the state’s two wolf management zones. Chapter III (Wolf as Special Status Game Mammal) is a new chapter comprised of content from the previous plan and addresses the Special Status Game Mammal definition and conditions of that definition. Chapter IV (Wolf-Livestock Conflicts) includes information on the use of non-lethal deterrents, the use of controlled take in certain situations, and expands livestock producer options for investigating potential wolf depredations of livestock. Chapter V (Wolf- Ungulate Interactions, and Interactions With Other Carnivores) addresses interactions between and impacts of wolves and other wildlife species. Chapter VI (Wolf-Human Interactions) addresses the types of wolf-human interactions and strategies for reducing negative situations. -

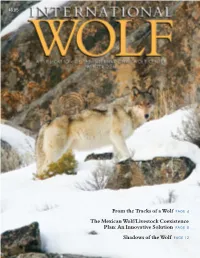

An Innovative Solution PAGE 8 Shadows of the Wolf

$6.95 From the Tracks of a Wolf PAGE 4 The Mexican Wolf/Livestock Coexistence Plan: An Innovative Solution PAGE 8 Shadows of the Wolf PAGE 12 Item 6667 $18.95 Deck the Halls with Howling Great Gifts! Item 9665-PARENT $25.00 Item 7223 $13.50 Item 3801 $14.95 Item 6610-PARENT $44.95 Order today at shop.wolf.org or call 1-800-ELY-WOLF VOLUME 24, NO. 4 THE QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WOLF CENTER WINTER 2014 4 David Moskowitz 8 Interagncy Field Team Mexican Wolf 12 Curtis ©Shutterstock.com/Tom From the Tracks of a Wolf The Mexican Wolf/ Shadows of the Wolf Livestock Coexistence Plan: By tracking wolf OR-7 for a An Innovative Solution The Eurasian wolf, sometimes month, a Wild Peace Alliance known as the common wolf or team consisting of a storyteller, A Mexican wolf recovery Middle Russian forest wolf, was wildlife tracker, documentary plan in New Mexico and prevalent throughout Britain and filmmaker, educator, multimedia Arizona avoids the problems Europe in ancient times. While producer and conservationist of traditional compensation it has long since been extinct in aimed to stimulate conversations programs by instead paying Britain, more than 200 place about wolf recovery and learn ranchers for the presence of names in the British Isles might from the people of the land wolves. This innovative program be associated with the former firsthand about their experiences has the potential to resolve a habitation of the Eurasian wolf. living close to wolves. long-standing conflict between ranchers and conservationists. By Robin Whitlock By Galeo Saintz By Sherry Barrett and Sisto Hernandez On the Cover Departments Wolf ’06: “The most famous wolf in the world.” 3 From the Photo by Jimmy Jones/Jimmy Jones Photography Executive Director Visit http://jimmyjonesphotography.com/ 14 Tracking the Pack for more images of Wolf ’06 and other wildlife. -

Exposure to Ideas, Evaluation Apprehension, and Incubation Intervals in Collaborative Idea Generation

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 04 July 2019 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01459 Exposure to Ideas, Evaluation Apprehension, and Incubation Intervals in Collaborative Idea Generation Xiang Zhou1,2, Hong-Kun Zhai1, Bibi Delidabieke1, Hui Zeng2,3*, Yu-Xin Cui1 and Xue Cao1 1Department of Social Psychology, Nankai University, Tianjin, China, 2 Department of International Business, School of Economics, Nankai University, Tianjin, China, 3 Collaborative Innovation Center for China Economy, Tianjin, China This study focused on the social factors and cognitive processes that influence collaborative idea generation, using the research paradigm of group idea generation, evaluation apprehension, and incubation. Specifically, it aimed to explore the impact of exposure to others’ ideas, evaluation apprehension, and incubation intervals on collaborative idea generation through three experiments. The results showed that in the process of generating ideas in a group, exposure to others’ ideas and evaluation apprehension can lead to Edited by: Linden John Ball, productivity deficits in the number and categories of ideas, without affecting the novelty University of Central Lancashire, of ideas. Further, exposure to others’ ideas and evaluation apprehension had an interaction United Kingdom effect on the number of ideas. As compared with the situation without exposure to others’ Reviewed by: idea, in that with exposure to others’ idea, evaluation apprehension had a weaker impact Ut Na Sio, The Education University of on the productivity of the number of ideas. -

Quantification of the Service Life Extension and Environmental

materials Article Quantification of the Service Life Extension and Environmental Benefit of Chloride Exposed Self-Healing Concrete Bjorn Van Belleghem 1,2, Philip Van den Heede 1,2, Kim Van Tittelboom 1 and Nele De Belie 1,* 1 Magnel Laboratory for Concrete Research, Department of Structural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Ghent University, Tech Lane Ghent Science Park, Campus A, Technologiepark Zwijnaarde 904, B-9052 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] (B.V.B.); [email protected] (P.V.d.H.); [email protected] (K.V.T.) 2 Strategic Initiative Materials (SIM vzw), Project ISHECO within the Program “SHE”, Tech Lane Ghent Science Park, Campus A, Technologiepark Zwijnaarde 935, B-9052 Ghent, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-9-264-5522 Academic Editor: Prabir K. Sarker Received: 14 November 2016; Accepted: 16 December 2016; Published: 23 December 2016 Abstract: Formation of cracks impairs the durability of concrete elements. Corrosion inducing substances, such as chlorides, can enter the matrix through these cracks and cause steel reinforcement corrosion and concrete degradation. Self-repair of concrete cracks is an innovative technique which has been studied extensively during the past decade and which may help to increase the sustainability of concrete. However, the experiments conducted until now did not allow for an assessment of the service life extension possible with self-healing concrete in comparison with traditional (cracked) concrete. In this research, a service life prediction of self-healing concrete was done based on input from chloride diffusion tests. Self-healing of cracks with encapsulated polyurethane precursor formed a partial barrier against immediate ingress of chlorides through the cracks. -

Combating Hidden and Exposed Terminal Problems in Wireless Networks Lu Wang, Student Member, IEEE, Kaishun Wu, Member, IEEE, and Mounir Hamdi, Fellow, IEEE

4204 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON WIRELESS COMMUNICATIONS, VOL. 11, NO. 11, NOVEMBER 2012 Combating Hidden and Exposed Terminal Problems in Wireless Networks Lu Wang, Student Member, IEEE, Kaishun Wu, Member, IEEE, and Mounir Hamdi, Fellow, IEEE Abstract—The hidden terminal problem is known to degrade the exposed node and excludes a collided transmission by the throughput of wireless networks due to collisions, while consulting a “Conflict Map”, but the hidden terminal problem the exposed terminal problem results in poor performance by becomes even more acute. Carrier Sense Multiple Access wasting valuable transmission opportunities. As a result, exten- sive research has been conducted to solve these two problems, with Collision Avoidance (CSMA/CA) designs a handshake such as Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Avoidance mechanism called RTS/CTS [4] to mitigate both the hidden (CSMA/CA). However, CSMA-like protocols cannot solve both of and the exposed terminal problems. However, RTS/CTS in- these two problems at once. The fundamental reason lies in the duces a rather high cost and introduces other problems like fact that they cannot obtain accurate Channel Usage Information false blocking. Therefore, RTS/CTS is disabled by default in (CUI, who is transmitting or receiving nearby) with a low cost. To obtain additional CUI in a cost-efficient way, we propose WLANs. a cross layer design, FAST (Full-duplex Attachment System). When trying to solve both the hidden and the exposed FAST contains a PHY layer Attachment Coding,whichtransmits terminal problems, a tradeoff arises between collisions (hidden control information independently on the air, without degrading nodes) and unused capacities (exposed nodes).