Walking on Thin Ice: a Balanced Arctic Strategy for the EU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

New Siberian Islands Archipelago)

Detrital zircon ages and provenance of the Upper Paleozoic successions of Kotel’ny Island (New Siberian Islands archipelago) Victoria B. Ershova1,*, Andrei V. Prokopiev2, Andrei K. Khudoley1, Nikolay N. Sobolev3, and Eugeny O. Petrov3 1INSTITUTE OF EARTH SCIENCE, ST. PETERSBURG STATE UNIVERSITY, UNIVERSITETSKAYA NAB. 7/9, ST. PETERSBURG 199034, RUSSIA 2DIAMOND AND PRECIOUS METAL GEOLOGY INSTITUTE, SIBERIAN BRANCH, RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, LENIN PROSPECT 39, YAKUTSK 677980, RUSSIA 3RUSSIAN GEOLOGICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE (VSEGEI), SREDNIY PROSPECT 74, ST. PETERSBURG 199106, RUSSIA ABSTRACT Plate-tectonic models for the Paleozoic evolution of the Arctic are numerous and diverse. Our detrital zircon provenance study of Upper Paleozoic sandstones from Kotel’ny Island (New Siberian Island archipelago) provides new data on the provenance of clastic sediments and crustal affinity of the New Siberian Islands. Upper Devonian–Lower Carboniferous deposits yield detrital zircon populations that are consistent with the age of magmatic and metamorphic rocks within the Grenvillian-Sveconorwegian, Timanian, and Caledonian orogenic belts, but not with the Siberian craton. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test reveals a strong similarity between detrital zircon populations within Devonian–Permian clastics of the New Siberian Islands, Wrangel Island (and possibly Chukotka), and the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago. These results suggest that the New Siberian Islands, along with Wrangel Island and the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago, were located along the northern margin of Laurentia-Baltica in the Late Devonian–Mississippian and possibly made up a single tectonic block. Detrital zircon populations from the Permian clastics record a dramatic shift to a Uralian provenance. The data and results presented here provide vital information to aid Paleozoic tectonic reconstructions of the Arctic region prior to opening of the Mesozoic oceanic basins. -

Geography Notes.Pdf

THE GLOBE What is a globe? a small model of the Earth Parts of a globe: equator - the line on the globe halfway between the North Pole and the South Pole poles - the northern-most and southern-most points on the Earth 1. North Pole 2. South Pole hemispheres - half of the earth, divided by the equator (North & South) and the prime meridian (East and West) 1. Northern Hemisphere 2. Southern Hemisphere 3. Eastern Hemisphere 4. Western Hemisphere continents - the largest land areas on Earth 1. North America 2. South America 3. Europe 4. Asia 5. Africa 6. Australia 7. Antarctica oceans - the largest water areas on Earth 1. Atlantic Ocean 2. Pacific Ocean 3. Indian Ocean 4. Arctic Ocean 5. Antarctic Ocean WORLD MAP ** NOTE: Our textbooks call the “Southern Ocean” the “Antarctic Ocean” ** North America The three major countries of North America are: 1. Canada 2. United States 3. Mexico Where Do We Live? We live in the Western & Northern Hemispheres. We live on the continent of North America. The other 2 large countries on this continent are Canada and Mexico. The name of our country is the United States. There are 50 states in it, but when it first became a country, there were only 13 states. The name of our state is New York. Its capital city is Albany. GEOGRAPHY STUDY GUIDE You will need to know: VOCABULARY: equator globe hemisphere continent ocean compass WORLD MAP - be able to label 7 continents and 5 oceans 3 Large Countries of North America 1. United States 2. Canada 3. -

World Transport Market and Logistics Project

World Transport Market and Logistics Project KO1029 Barents Region Transport and Logistics Report 15.5.2020 CONTENTS This report includes the following sections 1 Background and goals of the study p. 2-3 2 The implementer's recommendations and conclusions p. 4-6 Barents Region as a transportation and logistics p. 7-32 3 operating environment today 4 The signals of change p. 33-51 5 Scenarios of the future p. 52-83 1 1 Background and goals of the study 2 BACKGROUND AND GOALS The report examines the current state of different logistics and transportation flows in the Barents Region and creates understanding on the area’s future competitiveness Barents Region is under a transformation The rich natural resources of the Barents Region and growing tourism cause effects to the logistics chains and different material flows from and to the area. The fishing industry is developing and is moving towards the THE RESEARCH QUESTIONS OF THE REPORT ARE North and to new spheres. In addition to these changes, the Northeast passage offers a faster transportation route between Asia and Europe, Phase 1: AS-IS analysis Phase 2: Future scenarios that has big impacts on the development of the Barents Region. At the same time, the industries in the are face still the problem of reachability. 1. What kinds of different goods-, cargo- 1. What is the competitiveness of the Investments in mining-, energy production and fishery are not possible and tourism flows are moving in the Barents Region in the Global market without good connectivity to different markets. Barents Region at the moment? in 2030 and 2040? Understanding the current situation is vital 2. -

Arctic Species Trend Index 2010

Arctic Species Trend Index 2010Tracking Trends in Arctic Wildlife CAFF CBMP Report No. 20 discover the arctic species trend index: www.asti.is ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Directorate for Nature Management, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • The Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment, the Environmental Agency, the Government of Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organisations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ICC) Greenland, Alaska and Canada • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • The Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Louise McRae, Christoph Zöckler, Michael Gill, Jonathan Loh, Julia Latham, Nicola Harrison, Jenny Martin and Ben Collen. 2010. Arctic Species Trend Index 2010: Tracking Trends in Arctic Wildlife. CAFF CBMP Report No. 20, CAFF International Secretariat, Akureyri, Iceland. For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Website: www.caff.is Design & Layout: Lily Gontard Cover photo courtesy of Joelle Taillon. March 2010 ___ CAFF Designated Area Report Authors: Louise McRae, Christoph Zöckler, Michael Gill, Jonathan Loh, Julia Latham, Nicola Harrison, Jenny Martin and Ben Collen This report was commissioned by the Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program (CBMP) with funding provided by the Government of Canada. -

Arctic Council: Navigating Global Change

At a glance February 2015 Arctic Council: navigating global change Climate change and globalisation have increased the focus on the Arctic region and thus on the Arctic Council (AC) as a circumpolar player. Ahead of the ministerial meeting in April 2015 – where the AC will decide on the EU's bid for observer status – preparations for the US to take over the rotating chairmanship for 2015-17 are rekindling debate on the AC's future priorities and role. Informal forum for Arctic cooperation The inter-governmental Arctic Council (AC) was founded in 1996 by the five Arctic coastal states, Canada, Denmark (including Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Norway, Russia, and the United States, plus Finland, Iceland and Sweden, as a 'high level forum' to promote sustainable development and environmental protection. Since then, the AC has continued to develop its organisational structures, for example by making the temporary secretariat in Tromsø, Norway, permanent in 2013. However, the AC lacks legal personality and formally speaking is not an international organisation. Its decisions and standards are consensual and non-binding, and it does not impose policies or payments on its member states. On the basis of this soft legal status, the AC has established itself as a key forum for Arctic scientific and policy cooperation. Between the biennial AC Ministerial Meetings, the eight member states are represented by appointed national Senior Arctic Officials (SAOs), who meet at least twice a year. The current membership would only change if Greenland were to gain full independence, causing Denmark to lose its status as an Arctic state. -

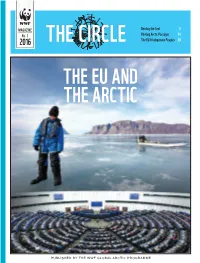

The Eu and the Arctic

MAGAZINE Dealing the Seal 8 No. 1 Piloting Arctic Passages 14 2016 THE CIRCLE The EU & Indigenous Peoples 20 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC PUBLISHED BY THE WWF GLOBAL ARCTIC PROGRAMME TheCircle0116.indd 1 25.02.2016 10.53 THE CIRCLE 1.2016 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC Contents EDITORIAL Leaving a legacy 3 IN BRIEF 4 ALYSON BAILES What does the EU want, what can it offer? 6 DIANA WALLIS Dealing the seal 8 ROBIN TEVERSON ‘High time’ EU gets observer status: UK 10 ADAM STEPIEN A call for a two-tier EU policy 12 MARIA DELIGIANNI Piloting the Arctic Passages 14 TIMO KOIVUROVA Finland: wearing two hats 16 Greenland – walking the middle path 18 FERNANDO GARCES DE LOS FAYOS The European Parliament & EU Arctic policy 19 CHRISTINA HENRIKSEN The EU and Arctic Indigenous peoples 20 NICOLE BIEBOW A driving force: The EU & polar research 22 THE PICTURE 24 The Circle is published quar- Publisher: Editor in Chief: Clive Tesar, COVER: terly by the WWF Global Arctic WWF Global Arctic Programme [email protected] (Top:) Local on sea ice in Uumman- Programme. Reproduction and 8th floor, 275 Slater St., Ottawa, naq, Greenland. quotation with appropriate credit ON, Canada K1P 5H9. Managing Editor: Becky Rynor, Photo: Lawrence Hislop, www.grida.no are encouraged. Articles by non- Tel: +1 613-232-8706 [email protected] (Bottom:) European Parliament, affiliated sources do not neces- Fax: +1 613-232-4181 Strasbourg, France. sarily reflect the views or policies Design and production: Photo: Diliff, Wikimedia Commonss of WWF. Send change of address Internet: www.panda.org/arctic Film & Form/Ketill Berger, and subscription queries to the [email protected] ABOVE: Sarek glacier, Sarek National address on the right. -

A Newly Discovered Glacial Trough on the East Siberian Continental Margin

Clim. Past Discuss., doi:10.5194/cp-2017-56, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Clim. Past Discussion started: 20 April 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. De Long Trough: A newly discovered glacial trough on the East Siberian Continental Margin Matt O’Regan1,2, Jan Backman1,2, Natalia Barrientos1,2, Thomas M. Cronin3, Laura Gemery3, Nina 2,4 5 2,6 7 1,2,8 9,10 5 Kirchner , Larry A. Mayer , Johan Nilsson , Riko Noormets , Christof Pearce , Igor Semilietov , Christian Stranne1,2,5, Martin Jakobsson1,2. 1 Department of Geological Sciences, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 106 91, Sweden 2 Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden 10 3 US Geological Survey MS926A, Reston, Virginia, 20192, USA 4 Department of Physical Geography (NG), Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 5 Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, New Hampshire 03824, USA 6 Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 106 91, Sweden 7 University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS), P O Box 156, N-9171 Longyearbyen, Svalbard 15 8 Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, 8000, Denmark 9 Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 690041 Vladivostok, Russia 10 Tomsk National Research Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia Correspondence to: Matt O’Regan ([email protected]) 20 Abstract. Ice sheets extending over parts of the East Siberian continental shelf have been proposed during the last glacial period, and during the larger Pleistocene glaciations. The sparse data available over this sector of the Arctic Ocean has left the timing, extent and even existence of these ice sheets largely unresolved. -

Black Carbon and Methane in the Norwegian Barents Region Black Carbon and Methane in the Norwegian Barents Region | M276

REPORT M-276 | 2014 Black carbon and methane in the Norwegian Barents region Black carbon and methane in the Norwegian Barents region | M276 COLOPHON Executive institution The Norwegian Environment Agency Project manager for the contractor Contact person in the Norwegian Environment Agency Ingrid Lillehagen, The Ministry of Climate and Solrun Figenschau Skjellum Environment, section for polar affairs and the High North M-no Year Pages Contract number M-276 2014 15 Publisher The project is funded by The Norwegian Environment Agency The Norwegian Environment Agency Author(s) Maria Malene Kvalevåg, Vigdis Vestreng and Nina Holmengen Title – Norwegian and English Black carbon and methane in the Norwegian Barents Region Svart karbon og metan i den norske Barentsregionen Summary – sammendrag In 2011, land based emissions of black carbon and methane in the Norwegian Barents region were 400 tons and 23 700 tons, respectively. The largest emissions of black carbon originate from the transport sector and wood combustion in residential heating. For methane, the largest contributors to emissions are the agricultural sector and landfills. Different measures to reduce emissions from black carbon and methane can be implemented. Retrofitting of diesel particulate filters on light and heavy vehicles, tractors and construction machines will reduce black carbon emitted from the transport sector. Measures to reduce black carbon from residential heating are to accelerate the introduction of wood stoves with cleaner burning, improve burning techniques and inspect and maintain the wood stoves that are already in use. In the agricultural sector, methane emissions from food production can be reduced by using manure or food waste as raw material to biogas production. -

"New Winds in the Barents Region"

"NEW WINDS IN THE BARENTS REGION" 2nd Programme of Cultural Cooperation 2008-2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION BACKGROUND OF THE BARENTS REGION AND COOPERATION STRUCTURE Barents Region Cooperation structure PART A CULTURAL POLICY PROGRAMME 2008 - 2010 1. General basis for the Programme 2. Objectives for cooperation 2.1. Cultural diversity and multicultural dialogue 2.2. Culture as a tool for regional, social and economic development 2.3. New cultural meeting places 3. Activities 4. Monitoring and evaluation 5. Funding PART B ACTION PLAN AND PROJECTS www.barentsinfo.org, www.barentsculture.ru. ANNEX - Mandate of JWGC - Kirkenes Declaration 1993 - Arkhangelsk Communiqué 1998 - Oulu Communiqué 2002 INTRODUCTION "Cultural sphere, in the full sense of it, includes social experience and a concept as well as economic, legal, scientific, moral and ethnical values Culture includes not only culture and arts, but also the way of life and system of values. In this sense culture becomes the major power for intellectual renewal and human perfection» (the European Council Report on European Cultural Policy) Culture plays a fundamental role in human and regional development in the Barents Region. The Programme of Cultural Cooperation 2008-2010 "New Winds in the Barents Region" is the framework for inter-regional cultural cooperation in the Barents Euro-Arctic Region. It highlights cultural diversity and the importance of culture and cultural industry as a unique tool for the development of the region. The cultural potential must be recognised and utilized to the full. This is the second Cultural Programme since Barents cooperation in the field of culture started in 1993. The first programme "Voices in the Barents Region" was implemented in the period of 2003-2006. -

Natural Variability of the Arctic Ocean Sea Ice During the Present Interglacial

Natural variability of the Arctic Ocean sea ice during the present interglacial Anne de Vernala,1, Claude Hillaire-Marcela, Cynthia Le Duca, Philippe Robergea, Camille Bricea, Jens Matthiessenb, Robert F. Spielhagenc, and Ruediger Steinb,d aGeotop-Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, QC H3C 3P8, Canada; bGeosciences/Marine Geology, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, 27568 Bremerhaven, Germany; cOcean Circulation and Climate Dynamics Division, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research, 24148 Kiel, Germany; and dMARUM Center for Marine Environmental Sciences and Faculty of Geosciences, University of Bremen, 28334 Bremen, Germany Edited by Thomas M. Cronin, U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Jean Jouzel August 26, 2020 (received for review May 6, 2020) The impact of the ongoing anthropogenic warming on the Arctic such an extrapolation. Moreover, the past 1,400 y only encom- Ocean sea ice is ascertained and closely monitored. However, its pass a small fraction of the climate variations that occurred long-term fate remains an open question as its natural variability during the Cenozoic (7, 8), even during the present interglacial, on centennial to millennial timescales is not well documented. i.e., the Holocene (9), which began ∼11,700 y ago. To assess Here, we use marine sedimentary records to reconstruct Arctic Arctic sea-ice instabilities further back in time, the analyses of sea-ice fluctuations. Cores collected along the Lomonosov Ridge sedimentary archives is required but represents a challenge (10, that extends across the Arctic Ocean from northern Greenland to 11). Suitable sedimentary sequences with a reliable chronology the Laptev Sea were radiocarbon dated and analyzed for their and biogenic content allowing oceanographical reconstructions micropaleontological and palynological contents, both bearing in- can be recovered from Arctic Ocean shelves, but they rarely formation on the past sea-ice cover.