Bertram Goodhue Index, Avery Library, Columbia University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1875 El Prado San Diego, CA 92101 (619) 238-1233

Volunteer Orientation Handbook 1875 El Prado San Diego, CA 92101 (619) 238-1233 www.rhfleet.org The Reuben H. Fleet Science Center seeks to inspire lifelong learning by furthering the public understanding and enjoyment of science and technology. Welcome Welcome to the Volunteer and Internship Programs at the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center. We thank you for your interest in helping our organization inspire lifelong learning in our community. We sincerely hope that your experiences here will be rewarding, educational and fun! Volunteers and interns play an integral role in the operation of the Fleet and its programs. Our team is made up of over 200 dedicated volunteers and interns (and roughly 100 employees) serving in a multitude of roles, all helping to spark a better understanding and enjoyment of science and technology by the public. We would like to express our sincere appreciation for your interest in our volunteer and intern programs. We couldn't do any of this without your support. THANK YOU for sharing your time and talent with us! General Information Mission Statement: The Reuben H. Fleet Science Center seeks to inspire lifelong learning by furthering the public understanding and enjoyment of science and technology. Physical Address: 1875 El Prado (at the intersection of Park Blvd. & Space Theater Way) San Diego, CA 92101 Mailing Address: PO Box 33303 San Diego, CA 92163 Telephone: (619) 238-1233 Website: www.rhfleet.org Hours: Open every day, including holidays! We open every day at 10:00 a.m. (exception: 11:30 a.m. on Christmas day). Closing times vary—check our website for updates. -

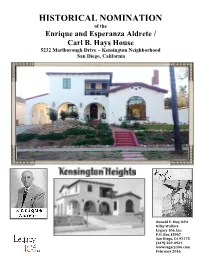

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House 5232 Marlborough Drive ~ Kensington Neighborhood San Diego, California Ronald V. May, RPA Kiley Wallace Legacy 106, Inc. P.O. Box 15967 San Diego, CA 92175 (619) 269-3924 www.legacy106.com February 2016 1 HISTORIC HOUSE RESEARCH Ronald V. May, RPA, President and Principal Investigator Kiley Wallace, Vice President and Architectural Historian P.O. Box 15967 • San Diego, CA 92175 Phone (619) 269-3924 • http://www.legacy106.com 2 3 State of California – The Resources Agency Primary # ___________________________________ DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # ______________________________________ PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial __________________________________ NRHP Status Code 3S Other Listings ___________________________________________________________ Review Code _____ Reviewer ____________________________ Date __________ Page 3 of 38 *Resource Name or #: The Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House P1. Other Identifier: 5232 Marlborough Drive, San Diego, CA 92116 *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County: San Diego and (P2b and P2c or P2d. Attach a Location Map as necessary.) *b. USGS 7.5' Quad: La Mesa Date: 1997 Maptech, Inc.T ; R ; ¼ of ¼ of Sec ; M.D. B.M. c. Address: 5232 Marlborough Dr. City: San Diego Zip: 92116 d. UTM: Zone: 11 ; mE/ mN (G.P.S.) e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, etc.) Elevation: 380 feet Legal Description: Lots Three Hundred Twenty-three and Three Hundred Twenty-four of KENSINGTON HEIGHTS UNIT NO. 3, according to Map thereof No. 1948, filed in the Office of the County Recorder, San Diego County, September 28, 1926. It is APN # 440-044-08-00 and 440-044-09-00. -

Arciiltecture

· BALBOA PARK· CENTRAL MESA PRECISE PLAN Precise Plan • Architecture ARCIIlTECTURE The goal of this section is to rehabilitate and modify the architecture of the Central Mesa ina manner which preserves its historic and aesthetic significance while providing for functional needs. The existing structures built for the 1915 and the 1935 Expositions are both historically and architecturally significant and should be reconstructed or rehabilitated. Not only should the individual structures be preserved, but the entire ensemble in its original composition should be preserved and restored wherever possible. It is the historic relationship between the built and the outdoor environment that is the hallmark of the two Expositions. Because each structure affects its site context to such a great degree, it is vital to the preservation of the historic district that every effort be made to preserve and restore original Exposition building footprints and elevations wherever possible. For this reason, emphasis has been placed on minimizing architectural additions unless they are reconstructions of significant historical features. Five major types of architectural modifications are recommended for the Central Mesa and are briefly described below. 1. Preservation and maintenance of existing structures. In the case of historically significant architecture, this involves preserving the historical significance of the structure and restoring lost historical features wherever possible. Buildings which are not historically significant should be preserved and maintained in good condition. 2. Reconstructions . This type of modification involves the reconstruction of historic buildings that have deteriorated to a point that prevents rehabilitation of the existing structure. This type of modification also includes the reconstruction of historically significant architectural features that have been lost. -

Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Balboa Park Cultural Partnership Contact: Michael Warburton [email protected] Mobile (619) 850-4677 Website: Explorer.balboapark.org Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend San Diego, CA – March 31 – The Balboa Park Cultural Partnership (BPCP) announced that today the parkwide Balboa Park Explorer Pass program has resumed the sale of day and annual passes, in advance of more museums reopening this Easter weekend and beyond. “The Explorer Pass is the easiest way to visit multiple museums in Balboa Park, and is a great value when compared to purchasing admission separately,” said Kristen Mihalko, Director of Operations for BPCP. “With more museums reopening this Friday, we felt it was a great time to restart the program and provide the pass for visitors to the Park.” Starting this Friday, April 2nd, the nonprofit museums available to visit with the Explorer Pass include: • Centro Cultural de la Raza, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • Japanese Friendship Garden, 7 days/week • San Diego Air and Space Museum, 7 days/week • San Diego Automotive Museum, 6 days/week, closed Monday • San Diego Model Railroad Museum, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • San Diego Museum of Art, 6 days/week, closed Wednesdays • San Diego Natural History Museum (The Nat), 5 days/week, closed Wednesday and Thursday The Fleet Science Center will rejoin the line up on April 9th; the Museum of Photographic Arts and the San Diego History Center will reopen on April 16th, and the Museum of Us will reopen on April 21st. -

Casa Del Prado in Balboa Park

Chapter 19 HISTORY OF THE CASA DEL PRADO IN BALBOA PARK Of buildings remaining from the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, exhibit buildings north of El Prado in the agricultural section survived for many years. They were eventually absorbed by the San Diego Zoo. Buildings south of El Prado were gone by 1933, except for the New Mexico and Kansas Buildings. These survive today as the Balboa Park Club and the House of Italy. This left intact the Spanish-Colonial complex along El Prado, the main east-west avenue that separated north from south sections The Sacramento Valley Building, at the head of the Plaza de Panama in the approximate center of El Prado, was demolished in 1923 to make way for the Fine Arts Gallery. The Southern California Counties Building burned down in 1925. The San Joaquin Valley and the Kern-Tulare Counties Building, on the promenade south of the Plaza de Panama, were torn down in 1933. When the Science and Education and Home Economy buildings were razed in 1962, the only 1915 Exposition buildings on El Prado were the California Building and its annexes, the House of Charm, the House of Hospitality, the Botanical Building, the Electric Building, and the Food and Beverage Building. This paper will describe the ups and downs of the 1915 Varied Industries and Food Products Building (1935 Food and Beverage Building), today the Casa del Prado. When first conceived the Varied Industries and Food Products Building was called the Agriculture and Horticulture Building. The name was changed to conform to exhibits inside the building. -

Balboa Park Facilities

';'fl 0 BalboaPark Cl ub a) Timken MuseumofArt ~ '------___J .__ _________ _J o,"'".__ _____ __, 8 PalisadesBuilding fDLily Pond ,------,r-----,- U.,..p_a_s ..,.t,..._---~ i3.~------ a MarieHitchcock Puppet Theatre G BotanicalBuild ing - D b RecitalHall Q) Casade l Prado \ l::..-=--=--=---:::-- c Parkand Recreation Department a Casadel Prado Patio A Q SanD iegoAutomot iveMuseum b Casadel Prado Pat io B ca 0 SanD iegoAerospace Museum c Casadel Prado Theate r • StarlightBow l G Casade Balboa 0 MunicipalGymnasium a MuseumofPhotograph icArts 0 SanD iegoHall of Champions b MuseumofSan Diego History 0 Houseof PacificRelat ionsInternational Cottages c SanDiego Mode l RailroadMuseum d BalboaArt Conservation Cente r C) UnitedNations Bui lding e Committeeof100 G Hallof Nations u f Cafein the Park SpreckelsOrgan Pavilion 4D g SanDiego Historical Society Research Archives 0 JapaneseFriendship Garden u • G) CommunityChristmas Tree G Zoro Garden ~ fI) ReubenH.Fleet Science Center CDPalm Canyon G) Plaza deBalboa and the Bea Evenson Fountain fl G) HouseofCharm a MingeiInternationa l Museum G) SanDiego Natural History Museum I b SanD iegoArt I nstitute (D RoseGarden j t::::J c:::i C) AlcazarGarden (!) DesertGarden G) MoretonBay Ag T ree •........ ••• . I G) SanDiego Museum ofMan (Ca liforniaTower) !il' . .- . WestGate (D PhotographicArts Bui lding ■ • ■ Cl) 8°I .■ m·■ .. •'---- G) CabrilloBridge G) SpanishVillage Art Center 0 ... ■ .■ :-, ■ ■ BalboaPar kCarouse l ■ ■ LawnBowling Greens G 8 Cl) I f) SeftonPlaza G MiniatureRail road aa a Founders'Plaza Cl)San Diego Zoo Entrance b KateSessions Statue G) War MemorialBuil ding fl) MarstonPoint ~ CentroCu lturalde la Raza 6) FireAlarm Building mWorld Beat Cultura l Center t) BalboaClub e BalboaPark Activ ity Center fl) RedwoodBrid geCl ub 6) Veteran'sMuseum and Memo rial Center G MarstonHouse and Garden e SanDiego American Indian Cultural Center andMuseum $ OldG lobeTheatre Comp lex e) SanDiego Museum ofArt 6) Administration BuildingCo urtyard a MayS. -

APPLIED NUTRITIONAL STUDIES with ZOOLOGICAL REPTILES by KYLE SAMUEL THOMPSON Bachelor of Science in Animal Science California S

APPLIED NUTRITIONAL STUDIES WITH ZOOLOGICAL REPTILES By KYLE SAMUEL THOMPSON Bachelor of Science in Animal Science California State University Fresno Fresno, California 2006 Master of Science in Animal Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2016 APPLIED NUTRITIONAL STUDIED WITH ZOOLOGICAL REPTILES Dissertation Approved: Dr. Clint Krehbiel Dissertation Adviser Dr. Gerald Horn Dr. Scott Carter Dr. Lionel Dawson ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “Until one has loved an animal, a part of one's soul remains unawakened." -Anatole France First and foremost, I would like to thank my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. He has always provided a light for me during times of discouragement. Secondly I would like to give a very big thank you to my advisor and mentor Dr. Clint Krehbiel who has been very patient and caring all these years. Thank you for all the guidance and giving me the freedom to pursue my dreams. I also want to extend a thank you to Donna Perry, Diana Batson, and Debra Danley for always being there for me to comfort and laugh. I would like to send a special thank you to the San Diego Zoo Nutrition Services team, Dr. Mike Schlegel, Edith Galindo and Michele Gaffney. Thank you for your guidance and patience and continued friendship. Further thank you is needed to Dr. Schlegel for accepting me in 2009 and opening my eyes to the world of zoo and captive wildlife nutrition. -

St. Bartholomew's Church and Community House: Draft Nomination

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S CHURCH AND COMMUNITY HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: St. Bartholomew’s Church and Community House Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 325 Park Avenue (previous mailing address: 109 East 50th Street) Not for publication: City/Town: New York Vicinity: State: New York County: New York Code: 061 Zip Code: 10022 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _X_ Public-Local: District: Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 buildings sites structures objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 2 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: DRAFT NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S CHURCH AND COMMUNITY HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival Into Balboa Park

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival into Balboa Park By Iris H.W. Engstrand G. Aubrey Davidson’s laudatory address to an excited crowd attending the opening of the Panama-California Exposition on January 1, 1915, gave no inkling that the Spanish Colonial architectural legacy that is so familiar to San Diegans today was ever in doubt. The buildings of this exposition have not been thrown up with the careless unconcern that characterizes a transient pleasure resort. They are part of the surroundings, with the aspect of permanence and far-seeing design...Here is pictured this happy combination of splendid temples, the story of the friars, the thrilling tale of the pioneers, the orderly conquest of commerce, coupled with the hopes of an El Dorado where life 1 can expand in this fragrant land of opportunity. G Aubrey Davidson, ca. 1915. ©SDHC #UT: 9112.1. As early as 1909, Davidson, then president of the Chamber of Commerce, had suggested that San Diego hold an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. When City Park was selected as the site in 1910, it seemed appropriate to rename the park for Spanish explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, who had discovered the Pacific Ocean and claimed the Iris H. W. Engstrand, professor of history at the University of San Diego, is the author of books and articles on local history including San Diego: California’s Cornerstone; Reflections: A History of the San Diego Gas and Electric Company 1881-1991; Harley Knox; San Diego’s Mayor for the People and “The Origins of Balboa Park: A Prelude to the 1915 Exposition,” Journal of San Diego History, Summer 2010. -

Plaza De Panama

WINTER 2010 www.C100.org PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The Balboa Park Alliance The Committee of One Hundred, The Balboa Park Trust at the San Diego Foundation, and Friends of Balboa Park share a common goal: to protect, preserve, and enhance Balboa Park. These three non-profi t organizations have formed Our Annual Appeal Help restore the Plaza de Panama. Make a check The Balboa Park Alliance (BPAL). Functioning to The Committee of One Hundred and mail it to: as an informal umbrella organization for nonprofi t groups committed to the enhancement of the Park, THE COMMITTEE OF ONE HUNDRED BPAL seeks to: Balboa Park Administration Building 2125 Park Boulevard • Leverage public support with private funding San Diego, CA 92103-4753 • Identify new and untapped revenue streams • Cultivate and engage existing donors has great potential. That partnership must have the • Attract new donors and volunteers respect and trust of the community. Will the City • Increase communication about the value of Balboa grant it suffi cient authority? Will the public have the Park to a broader public confi dence to support it fi nancially? • Encourage more streamlined delivery of services to The 2015 Centennial of the Panama-California the Park and effective project management Exposition is only fi ve years away. The legacy of • Advocate with one voice to the City and other that fi rst Exposition remains largely in evidence: authorizing agencies about the needs of the Park the Cabrillo Bridge and El Prado, the wonderful • Provide a forum for other Balboa Park support California Building, reconstructed Spanish Colonial groups to work together and leverage resources buildings, the Spreckels Organ Pavilion, the Botanical Building, and several institutions. -

The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915 by Richard W

The Journal of San Diego History SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY Winter 1990, Volume 36, Number 1 Thomas L. Scharf, Editor The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915 by Richard W. Amero Researcher and Writer on the history of Balboa Park Images from this article On July 9, 1901, G. Aubrey Davidson, founder of the Southern Trust and Commerce Bank and Commerce Bank and president of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, said San Diego should stage an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal. He told his fellow Chamber of Commerce members that San Diego would be the first American port of call north of the Panama Canal on the Pacific Coast. An exposition would call attention to the city and bolster an economy still shaky from the Wall Street panic of 1907. The Chamber of Commerce authorized Davidson to appoint a committee to look into his idea.1 Because the idea began with him, Davidson is called "the father of the exposition."2 On September 3, 1909, a special Chamber of Commerce committee formed the Panama- California Exposition Company and sent articles of incorporation to the Secretary of State in Sacramento.3 In 1910 San Diego had a population of 39,578, San Diego County 61,665, Los Angeles 319,198 and San Francisco 416,912. San Diego's meager population, the smallest of any city ever to attempt holding an international exposition, testifies to the city's extraordinary pluck and vitality.4 The Board of Directors of the Panama-California Exposition Company, on September 10, 1909, elected Ulysses S. -

Biographies of Established Masters

Biographies of Established Masters Historical Resources Board Jennifer Feeley Tricia Olsen, MCP Ricki Siegel Ginger Weatherford, MPS Historical Resources Board Staff 2011 i Master Architects Frank Allen Lincoln Rodgers George Adrian Applegarth Lloyd Ruocco Franklin Burnham Charles Salyers Comstock and Trotshe Rudolph Schindler C. E. Decker Thomas Shepherd Homer Delawie Edward Sibbert Edward Depew John Siebert Roy Drew George S. Spohr Russell Forester * John B. Stannard Ralph L. Frank Frank Stevenson George Gans Edgar V. Ullrich Irving Gill * Emmor Brooke Weaver Louis Gill William Wheeler Samuel Hamill Carleton Winslow William Sterling Hebbard John Lloyd Wright Henry H. Hester Eugene Hoffman Frank Hope, Sr. Frank L. Hope Jr. Clyde Hufbauer Herbert Jackson William Templeton Johnson Walter Keller Henry J. Lange Ilton E. Loveless Herbert Mann Norman Marsh Clifford May Wayne McAllister Kenneth McDonald, Jr. Frank Mead Robert Mosher Dale Naegle Richard Joseph Neutra O’Brien Brothers Herbert E. Palmer John & Donald B. Parkinson Wilbur D. Peugh Henry Harms Preibisius Quayle Brothers (Charles & Edward Quayle) Richard S. Requa Lilian Jenette Rice Sim Bruce Richards i Master Builders Juan Bandini Philip Barber Brawner and Hunter Carter Construction Company William Heath Davis The Dennstedt Building Company (Albert Lorenzo & Aaron Edward Dennstedt) David O. Dryden Jose Antonio Estudillo Allen H. Hilton Morris Irvin Fred Jarboe Arthur E. Keyes Juan Manuel Machado Archibald McCorkle Martin V. Melhorn Includes: Alberta Security Company & Bay City Construction Company William B. Melhorn Includes: Melhorn Construction Company Orville U. Miracle Lester Olmstead Pacific Building Company Pear Pearson of Pearson Construction Company Miguel de Pedroena, Jr. William Reed Nathan Rigdon R.P.