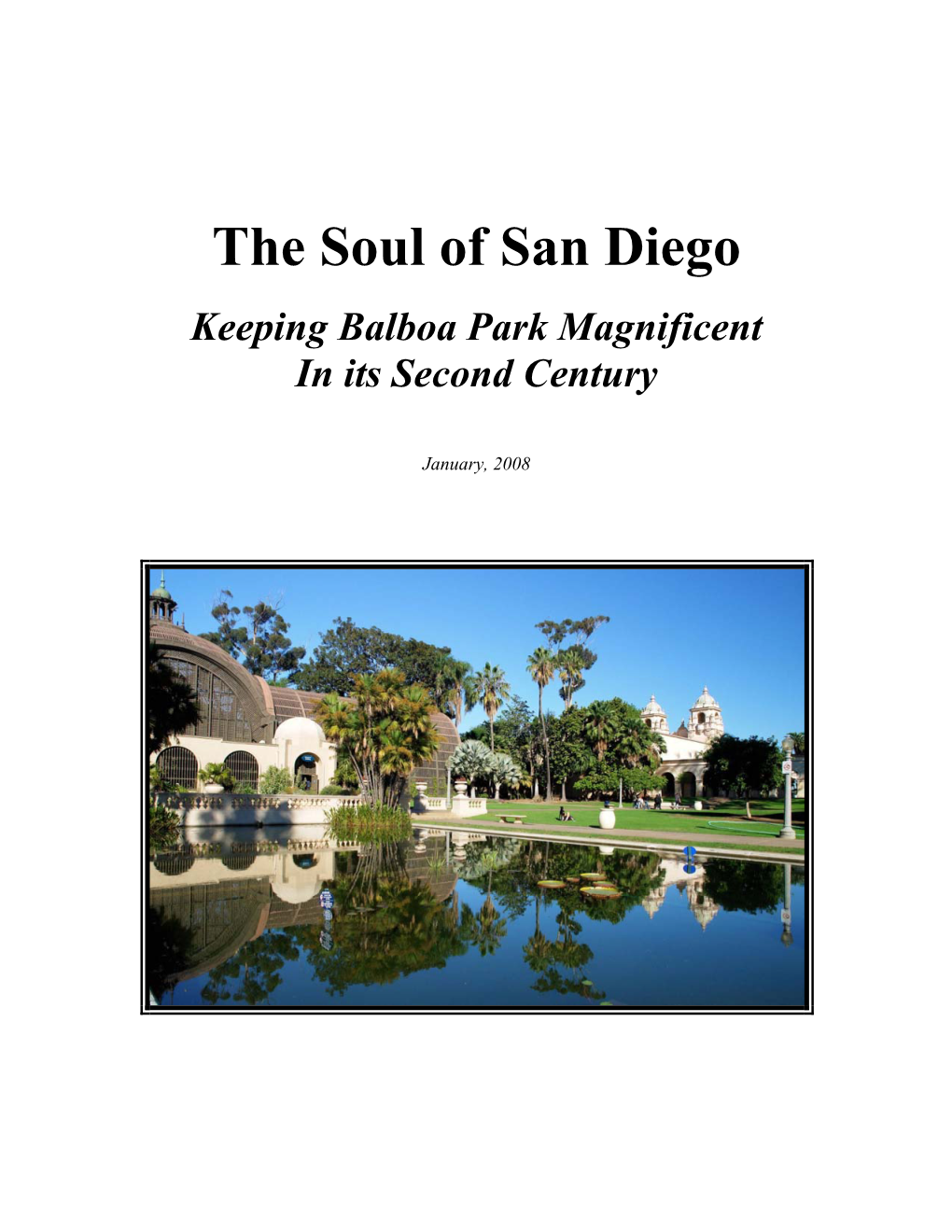

The Soul of San Diego: Keeping Balboa Park Magnificent in Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Balboa Park Cultural Partnership Contact: Michael Warburton [email protected] Mobile (619) 850-4677 Website: Explorer.balboapark.org Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend San Diego, CA – March 31 – The Balboa Park Cultural Partnership (BPCP) announced that today the parkwide Balboa Park Explorer Pass program has resumed the sale of day and annual passes, in advance of more museums reopening this Easter weekend and beyond. “The Explorer Pass is the easiest way to visit multiple museums in Balboa Park, and is a great value when compared to purchasing admission separately,” said Kristen Mihalko, Director of Operations for BPCP. “With more museums reopening this Friday, we felt it was a great time to restart the program and provide the pass for visitors to the Park.” Starting this Friday, April 2nd, the nonprofit museums available to visit with the Explorer Pass include: • Centro Cultural de la Raza, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • Japanese Friendship Garden, 7 days/week • San Diego Air and Space Museum, 7 days/week • San Diego Automotive Museum, 6 days/week, closed Monday • San Diego Model Railroad Museum, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • San Diego Museum of Art, 6 days/week, closed Wednesdays • San Diego Natural History Museum (The Nat), 5 days/week, closed Wednesday and Thursday The Fleet Science Center will rejoin the line up on April 9th; the Museum of Photographic Arts and the San Diego History Center will reopen on April 16th, and the Museum of Us will reopen on April 21st. -

Casa Del Prado in Balboa Park

Chapter 19 HISTORY OF THE CASA DEL PRADO IN BALBOA PARK Of buildings remaining from the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, exhibit buildings north of El Prado in the agricultural section survived for many years. They were eventually absorbed by the San Diego Zoo. Buildings south of El Prado were gone by 1933, except for the New Mexico and Kansas Buildings. These survive today as the Balboa Park Club and the House of Italy. This left intact the Spanish-Colonial complex along El Prado, the main east-west avenue that separated north from south sections The Sacramento Valley Building, at the head of the Plaza de Panama in the approximate center of El Prado, was demolished in 1923 to make way for the Fine Arts Gallery. The Southern California Counties Building burned down in 1925. The San Joaquin Valley and the Kern-Tulare Counties Building, on the promenade south of the Plaza de Panama, were torn down in 1933. When the Science and Education and Home Economy buildings were razed in 1962, the only 1915 Exposition buildings on El Prado were the California Building and its annexes, the House of Charm, the House of Hospitality, the Botanical Building, the Electric Building, and the Food and Beverage Building. This paper will describe the ups and downs of the 1915 Varied Industries and Food Products Building (1935 Food and Beverage Building), today the Casa del Prado. When first conceived the Varied Industries and Food Products Building was called the Agriculture and Horticulture Building. The name was changed to conform to exhibits inside the building. -

Balboa Park Facilities

';'fl 0 BalboaPark Cl ub a) Timken MuseumofArt ~ '------___J .__ _________ _J o,"'".__ _____ __, 8 PalisadesBuilding fDLily Pond ,------,r-----,- U.,..p_a_s ..,.t,..._---~ i3.~------ a MarieHitchcock Puppet Theatre G BotanicalBuild ing - D b RecitalHall Q) Casade l Prado \ l::..-=--=--=---:::-- c Parkand Recreation Department a Casadel Prado Patio A Q SanD iegoAutomot iveMuseum b Casadel Prado Pat io B ca 0 SanD iegoAerospace Museum c Casadel Prado Theate r • StarlightBow l G Casade Balboa 0 MunicipalGymnasium a MuseumofPhotograph icArts 0 SanD iegoHall of Champions b MuseumofSan Diego History 0 Houseof PacificRelat ionsInternational Cottages c SanDiego Mode l RailroadMuseum d BalboaArt Conservation Cente r C) UnitedNations Bui lding e Committeeof100 G Hallof Nations u f Cafein the Park SpreckelsOrgan Pavilion 4D g SanDiego Historical Society Research Archives 0 JapaneseFriendship Garden u • G) CommunityChristmas Tree G Zoro Garden ~ fI) ReubenH.Fleet Science Center CDPalm Canyon G) Plaza deBalboa and the Bea Evenson Fountain fl G) HouseofCharm a MingeiInternationa l Museum G) SanDiego Natural History Museum I b SanD iegoArt I nstitute (D RoseGarden j t::::J c:::i C) AlcazarGarden (!) DesertGarden G) MoretonBay Ag T ree •........ ••• . I G) SanDiego Museum ofMan (Ca liforniaTower) !il' . .- . WestGate (D PhotographicArts Bui lding ■ • ■ Cl) 8°I .■ m·■ .. •'---- G) CabrilloBridge G) SpanishVillage Art Center 0 ... ■ .■ :-, ■ ■ BalboaPar kCarouse l ■ ■ LawnBowling Greens G 8 Cl) I f) SeftonPlaza G MiniatureRail road aa a Founders'Plaza Cl)San Diego Zoo Entrance b KateSessions Statue G) War MemorialBuil ding fl) MarstonPoint ~ CentroCu lturalde la Raza 6) FireAlarm Building mWorld Beat Cultura l Center t) BalboaClub e BalboaPark Activ ity Center fl) RedwoodBrid geCl ub 6) Veteran'sMuseum and Memo rial Center G MarstonHouse and Garden e SanDiego American Indian Cultural Center andMuseum $ OldG lobeTheatre Comp lex e) SanDiego Museum ofArt 6) Administration BuildingCo urtyard a MayS. -

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival Into Balboa Park

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival into Balboa Park By Iris H.W. Engstrand G. Aubrey Davidson’s laudatory address to an excited crowd attending the opening of the Panama-California Exposition on January 1, 1915, gave no inkling that the Spanish Colonial architectural legacy that is so familiar to San Diegans today was ever in doubt. The buildings of this exposition have not been thrown up with the careless unconcern that characterizes a transient pleasure resort. They are part of the surroundings, with the aspect of permanence and far-seeing design...Here is pictured this happy combination of splendid temples, the story of the friars, the thrilling tale of the pioneers, the orderly conquest of commerce, coupled with the hopes of an El Dorado where life 1 can expand in this fragrant land of opportunity. G Aubrey Davidson, ca. 1915. ©SDHC #UT: 9112.1. As early as 1909, Davidson, then president of the Chamber of Commerce, had suggested that San Diego hold an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. When City Park was selected as the site in 1910, it seemed appropriate to rename the park for Spanish explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, who had discovered the Pacific Ocean and claimed the Iris H. W. Engstrand, professor of history at the University of San Diego, is the author of books and articles on local history including San Diego: California’s Cornerstone; Reflections: A History of the San Diego Gas and Electric Company 1881-1991; Harley Knox; San Diego’s Mayor for the People and “The Origins of Balboa Park: A Prelude to the 1915 Exposition,” Journal of San Diego History, Summer 2010. -

The Greening of Balboa Park: a Holistic, Sustainable and Replicable Model

The Greening of Balboa Park: A Holistic, Sustainable and Replicable Model Julieann Summerford, Heschong Mahone Group, Inc. Risa Baron, San Diego Gas & Electric Company Anna Stark, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Rory Ruppert, Balboa Park Cultural Partnership David McGrew, Reuben H. Fleet Science Center ABSTRACT Developed for the 1915 Panama Exposition, Balboa Park now houses more than two dozen major museums, performing arts organizations, gardens, and the San Diego Zoo. Located on over 1200 acres of land with over a million square feet of property, Balboa Park is one of the nation’s largest urban cultural centers, attracting more than 6.5 million visitors annually from around the world. Through recent collaborative efforts, Balboa Park is poised to become a national model for cultural institutions and urban parks to achieve environmental sustainability. In 2008 the Balboa Park Cultural Partnership established a Park-wide sustainability program that includes 26 cultural institutions, the City of San Diego, San Diego Gas & Electric, and many other community stakeholders. Designed to be a replicable model, the Partnership’s goals are the creation and alignment of sustainable business practices; the identification of, and communication with, key internal and external stakeholders; and the education of visitors, employees, stakeholders, and the public. All sustainability initiatives and results are benchmarked, measured and quantified—a vital component for measuring its carbon footprint and aligning with the state’s plan for energy efficiency. The Balboa Park Cultural Partnership (BPCP) has become the first network of cultural institutions in the country to benchmark the energy performance of its buildings using the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) ENERGY STAR® Portfolio Manager. -

The Southwest on Display at the Panama- California Exposition, 1915

The Journal of San Diego History SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY Fall 1990, Volume 36, Number 4 Richard W. Crawford, Editor The Southwest on Display at the Panama- California Exposition, 1915 By Richard W. Amero Images from the Article After five years of unrelenting effort, San Diego celebrated the official opening of the Panama- California Exposition in Balboa Park on January 1, 1915. At midnight, December 31, President Woodrow Wilson, in Washington, D.C., pressed a Western Union telegraph key. The signal turned on every light on the grounds and touched off a display of fireworks. The gates to the Exposition swung open. A crush of from 31,836 to 42,486 people on the grounds cheered, waved banners, threw confetti, sang "I Love You California," and snake-danced their way to the Isthmus, or fun street.1 Among the guests who took part in the official but sparsely attended ceremonies, beginning at 11:30 the following morning, were Secretary of the Treasury William G. McAdoo, Commander of the U.S. Pacific fleet Rear Admiral T.B. Howard, Director-General of the Pan-American Union John Barrett, and Spanish delegate Count del Valle de Salazar.2 In his speech to the guests, wearied from the festivities of the night before, Gilbert Aubrey Davidson, president of the Panama-California Exposition Company, declared the Exposition's purpose was to build an empire extending from the back country of the Pacific slope to the west shores of the Missouri River.3 At one point Davidson said: Here is pictured in this happy combination of splendid temples, the story of the friars, the thrilling tale of the pioneers, the orderly conquest of commerce, coupled with the hopes of an El Dorado where life can expand in this fragrant land of opportunity. -

History of the California Building and the San Diego Museum Of

CHAPTER 9 THE CALIFORNIA BUILDING: A CASE OF THE MISUNDERSTOOD BAROQUE AND THE HISTORY OF THE SAN DIEGO MUSEUM/ MUSEUM OF MAN by Richard W. Amero “My judgment is now clear and unfettered, and that dark cloud of ignorance has disappeared, which the continual reading of these detestable books of knight-errantry has cast over my understanding.” Miguel de Cervantes. Don Quixote, Book 2, Part 16. Very few people appear to have looked at the south facade of the California Building in San Diego's Balboa Park. H. K. Raymenton described it as Plateresque in style.[1] Trent Sanford thought it better than anything in Mexico or Spain.[2] William Templeton Johnson called it the finest Spanish- Renaissance facade in existence,[3] and Thomas E. Tallmadge hailed it as the best example of Churrigueresque architecture in the world.[4] An article in the San Diego Union, January 1, 1915, asserted the California Building was "copied in many essential details from the magnificent cathedral at Oaxaca, Mexico."[5] Christian Brinton repeated this suggestion in June of the same year.[6] After checking with Bertram Goodhue, who designed the California Building, C. Matlack Price referred to the comparison as "palpably absurd."[7] The Late-Renaissance Cathedral of Oaxaca, rebuilt in the early eighteenth century, has a compartmentalized facade with three horizontal tiers and five vertical bays which hold one principal and two lateral doorways, and is flanked by two squat, single-stage towers.[8] None of its details resemble those on the California Building. Carol Mendel declared the California Building facade was taken from the seventeenth to nineteenth-century late-Renaissance, Baroque, Neo- Classical facade of the Cathedral of Mexico in Mexico City.[9] If she had selected the mid-eighteenth century Sagrario Metropolitano, which adjoins the cathedral, she would have been closer to the truth, for this building's facade is an outstanding example of Mexican Ultra-Baroque, or, as it is generally known, Churrigueresque.[10] To George H. -

Public Notice Agenda

PUBLIC NOTICE AGENDA CITY OF SAN DIEGO PARK AND RECREATION BOARD BALBOA PARK COMMITTEE THURSDAY, MAY 1, 2008 5:30 P.M. *NOTE TIME CHANGE BALBOA PARK CLUB SANTA FE ROOM SAN DIEGO, CA 92101 Committee Members: IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO ATTEND THIS COMMITTEE MEETING, PLEASE CONTACT SHARON KNUTSON AT (619) 235-1157. CALL TO ORDER - Introductions APPROVAL OF MINUTES – April 3, 2008 REQUEST FOR CONTINUANCES NON AGENDA PUBLIC COMMENTS (Limited to items not on the agenda. Each one will be limited to three minutes (3 min.) and is not debatable.) CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT – Vicki Granowitz STAFF REPORT City Council Third District – Jeffery Tom Deputy Park and Recreation Director – Kathleen S Hasenauer Balboa Park Facilities/Special Events District Manager – Susan Lowery-Mendoza Balboa Park Operations District Manager – Bruce Martinez WORKSHOP ITEMS (No actions taken; subject discussed by the committee and staff.) 401. Balboa Park Study ACTION ITEMS Consent (These items are adopted without discussion; they can be moved to adoption by any committee member.) 101. None Adoption (Each adoption item requires individual action; they can be moved to consent by action of the committee.) 201. Proposed Fiscal Year 2009 Park & Rec. Budget- Stacey LoMedico, Park and Recreation Director Special Events (Special Events that require road or plaza closures, or will potentially impact park and/or institution operation, are brought to the Committee for a formal recommendation. They can be moved to consent by action of the committee.) 301. Cool Globes, Public Art Exhibit presented by Rita Alpert Cool Globes is an environmental art exhibit featuring 30-35 five foot in diameter, free- standing globes on concrete pedestals that were designed by various artists from around the world. -

Keeping Balboa Park Magnificent in Its Second Century

Prepared by The Trust for Public Land Center for City Park Excellence Washington, D.C. August 2006 Keeping Balboa Park Magnificent In its Second Century A Look at Management, Fundraising, and Private Partnerships at Five Other Major U.S. City Parks Balboa Park, San Diego. Photos Courtesy of Balboapark.org Introduction Covering 1,200 acres, containing an amazing 85 cultural, conservation and recreation organizations within its boundaries, and attracting upwards of 13 million visitors a year, San Diego’s Balboa Park ranks as one of the very most significant urban parks in America. Nevertheless, looking beyond the flamboyant Spanish architecture, exotic flora and man- icured lawn bowling fields, a park is revealed that is facing huge challenges, including hundreds of millions of dollars of repairs, a crisis of invasive plant species, unresolved issues about automobiles, large areas of contaminated land, a population of homeless per- sons, erosion, conflicts between user groups and - worst - an inability to keep up with day-to-day park maintenance. In order to help determine the best possible model for successfully and sustainably oper- ating a park as large and complex as Balboa, the Legler Benbough Foundation commis- sioned the Center for City Park Excellence (CCPE) to produce a short study of public- private partnerships operating in four other major cities: New York, St. Louis, Houston and Atlanta. Following a summary discussion of Balboa Park, the report describes the private support structures developed for Central Park and Prospect Park in New York, Forest Park in St. Louis, Piedmont Park in Atlanta and Hermann Park in Houston. -

The Bridges of San Diego County: the Art of Civil Engineering

The Bridges of San Diego County: The Art of Civil Engineering Christine Robbins Every bridge represents a problem solved, a challenge overcome, a connection made. San Diego, with its abundance of hills, mesas, and canyons, showcases the art of bridge building. Civil engineers took on the task and were lauded for their work in this poem: They have built magnificent bridges where the nation’s highways go; O’er perilous mountain ridges and where great rivers flow. Wherever a link was needed between the new and the known They have left their marks of Progress, in iron and steel and stone. There was never a land too distant nor ever a way too wide, But some man’s mind, insistent, reached out to the other side. They cleared the way, these heroes, for the march of future years. The march of Civilization—and they were its Pioneers. —Portion of “The Bridge Builders,” a poem by Evelyn Simms The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) considers bridges an important aspect of civil engineering. According to the organization’s policy statement; “Bridges are a visible icon of the Civil Engineer’s art. Historic bridges are important links to our past, serve as safe and vital transportation routes in the Author Christine Robbins acknowledges contributions by Civil Engineers Tim Shell, PE, of the City of Vista and Wade Durant, PE, Pete Smith, PE, ENV SP, and Clark Fernon, PE, of T.Y. Lin International. The author wishes to acknowledge all those who generously shared their recollections of working on some of the bridges discussed in the article. -

Casa Del Prado History

The Committee of One Hundred Panama-California Sculpture Court, Casa del Prado Courtyard History of the Casa del Prado Photo # Completed in 1971, the Casa del Prado is a modified reconstruction of the largest of the temporary exhibition 01 halls built in 1914 for the Panama-California Exposition of 1915-1916. The exposition celebrated the opening of the Panama Canal, which was expected to bring expanded trade and prosperity to the port cities of the Pacific Coast. Like the other Spanish Baroque style buildings of Balboa Park’s Central Mesa, the exterior of this building was designed as a part of a romantic and idealized evocation of a prosperous Spanish Colonial city of the early 18th Century. Although many of the ornamental features of these buildings were inspired by actual historical buildings in Spain and in Spain’s New World colonies, the intense richness of the exposition’s architecture was deliberately exaggerated to enhance the fun and fantasy experienced by the exposition’s visitors. The Panama-California Exposition’s Supervising Architect was Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue (1869-1924), of Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson, with offices in New York, Boston and Los Angeles. Goodhue controlled all design decisions for the exposition’s permanent and temporary structures, and employed two main assistants, Carleton Monroe Winslow (1876-1946), Project Architect, and Frank P. Allen, Jr. The Committee of One Hundred Panama-California Sculpture Court, Casa del Prado Courtyard (1881-1943), the project’s Chief Engineer and Director of Works. They are credited with the design of most of the exposition’s “temporary” buildings. The Casa del Prado’s original building was designed by Winslow. -

San Diego Invites the World to Balboa Park a Second Time by Richard W

The Journal of San Diego History SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY Fall 1985, Volume 31, Number 4 Thomas L. Scharf, Editor San Diego Invites the World to Balboa Park a Second Time by Richard W. Amero First Prize, Copley Award San Diego History Center 1985 Institute of History Images from this article THE California-Pacific International Exposition, held in Balboa Park in 1935-36, was a milepost in San Diego's history. Of the people who backed the exposition, architect-in-charge Richard Requa did the most to determine its final shape.1 Talk of holding a second exposition had begun before the 1915-16 Panama-California Exposition had closed. Instead of being torn down, as the exposition's master architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue had advised, the temporary buildings on Balboa Park's main avenue, El Prado, had been patched up in 1922 and again in 1933.2 In August 1933, Frank Drugan, former field representative for the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain, visited the renovated El Prado, admired its appearance, and suggested to San Diego businessmen that they use the buildings as the nucleus for a second exposition.3 As dynamic promoter for the second exposition, Drugan assumed the role Colonel "Charlie" Collier had taken for the first. Chicago's 1933-34 Century of Progress Exposition was in its final year. Many of its exhibits could be transported easily to San Diego. The exposition's promise of a happy and prosperous future had appealed to people beleaguered by the Great Depression.4 Frank G. Belcher, assistant cashier and vice president of the First National Trust and Savings Bank of San Diego, became the second exposition's president, the office G.