An Irish View of Scottish Mottes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cake & Cockhorse

CAKE & COCKHORSE BA JBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY SPRING 1984. PRICE fl.OO ISSN 0522-0823 I President: The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman: Mrs. G.W. Brinkworth, Flat 3, Calthorpe Manor, Dashwood Road, Banbury, 0x16, 8HE. Tel: Banbury 3000 Deputy chairman: J . S. W. Gibson, Harts Cottage, Church Hanborough, Oxford. OX7 2AB. Magazine Editor: D.A. Hitchcox, 1 Dorchester Grove, Broughton Road, Banbury. Tel: Banbury 53733 I Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: i Mrs N.M. Clifton, Miss Mary Stanton, Senendone House, 12 Kennedy House, I Shenington, Banbury. Orchard Way, Banbury. (Tel: Edge Hill 262) (Tel: 57754) Hon. Membership Secretary: Records Series Editor: Mrs Sarah Gosling, J.S.W. Gibson, Banbury Museum, Harts Cottage, 8 Horsefair, Banbury. Church Hanborough, Oxford OX7 2AB. (Tel: 59855) (Tel: Freeland (0993)882982) I' Committee Members: 'I Dr E. Asser, Mrs G. Beeston, Mr D.E.M. Fiennes Mrs Clare Jakeman, Mr G. de C. Parmiter, Mr J. F. Roberts Details about the Society's activities and publications can be found on the inside back cover The cover illustration is of a hawking scene taken by R. J. Ivens from a II medieval drawing published in Life and Work of the People of England (Batsford 1928) by D. Hartley and M. M. Elliot. CAKE & COCKHORSE The Magazine of the Banbury Historical Society. Issued three times a year. Volume 9 Number 5 Spring 1984 R.J. Ivens De Arte Venandi cum Avibus 130 Sarah Gosling The Banbury Trades Index 138 I Barbara Adkins The Old Vicarage, Horsefair, Banbury 139 D.E.M. Fiennes The Will of Nathaniel Fiennes 143 C.G. -

English Heritage Og Middelalderborgen

English Heritage og Middelalderborgen http://blog.english-heritage.org.uk/the-great-siege-of-dover-castle-1216/ Rasmus Frilund Torpe Studienr. 20103587 Aalborg Universitet Dato: 14. september 2018 Indholdsfortegnelse Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Indledning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Problemstilling ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Kulturarvsdiskussion ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Diskussion om kulturarv i England fra 1980’erne og frem ..................................................................... 5 Definition af Kulturarv ............................................................................................................................... 6 Hvordan har kulturarvsbegrebet udviklet sig siden 1980 ....................................................................... 6 Redegørelse for Historic England og English Heritage .............................................................................. 11 Begyndelsen på den engelske nationale samling ..................................................................................... 11 English -

Chapter 3: the Finds

Chapter 3: The Finds THE MEDIEVAL AND POST-MEDIEVAL A draft report on the pottery from the 1984 POTTERY (FIGS 3.1-11) excavations was written by Maureen Mellor in the by Cathy Keevill 1980s. The primary aim of the further analysis was to refine the site chronology and to understand the Summary development of the site. This involved adding in the An assemblage of 6779 sherds was recovered from pottery recovered from the 1988-1991 excavations, stratified contexts. The majority of these (a total of amending the context dates derived from the assoc 6317 or 93%) were medieval. This is the first iated pottery where necessary, and checking on the stratified sequence from Witney and as such is dating for the main types within the assemblage in highly important for the understanding of the order to establish a chronology that would corres development of 12th-century and early-13th-century pond to the Oxfordshire pottery sequence. Under pottery traditions in West Oxfordshire. The most standing the development of the major local fabric interesting feature of the assemblage was the range and vessel traditions in west Oxfordshire was also a of imported material from other regions, particularly priority, especially the calcareous gravel-tempered south-western England. These included fabric types fabric (Witney Fabric 1), which is similar to types in from Minety, Wiltshire (Fabrics 9 and 37), from the Cotswolds (Mellor 1994,72) and at Oxford (fabric Laverstock, south Wiltshire (Fabrics 5 and 25), types OXAC). known in Bath and Trowbridge (fabric 23), Newbury The analysis also included a consideration of the (Fabrics 2 and 3), Winchester (Fabric 8), and a status of the site (and of different areas within the possible Nash Hill product (Fabric 33). -

Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honour of Odo of Bayeux1 R.J

Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honour of Odo of Bayeux1 R.J. Ivens SUMMARY From an examination of Odo of Bayeux’s estate as recorded in Domesday Book, together with an analysis of the excavated structural phases at Deddington Castle, it is suggested that Deddington may have been the caput of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire parts of Odo’s barony. HISTORICAL EVIDENCE Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Earl of Kent, was one of the greatest of the tenants-in- chief of his half-brother King William, outstripping in wealth even such a magnate as his own brother Robert, Count of Mortain. Odo held lands in twenty-two English counties, and Domesday Book lists holdings in 456 separate manors. In all, these lands amounted to almost 1,700 hides worth over £3,000, and of these some 274 hides worth £534 were retained in demesne. The extent of these lands is far too great to consider in any detail, so only the distribution of the estates will be discussed here.2 Tables 1 and 2 list the extent of these holdings by county totals.3 The distribution of Odo’s estates may be seen more graphically on the maps, Figs. 1 and 2. Fig. 1, which shows the distribution of the individual manors, demonstrates that this distribution is far from random, and that several distinct clusterings may be observed, notably those around the Thames Estuary, in Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire, in Suffolk and in Lincolnshire. The maps presented in Fig. 2 are perhaps even more enlightening. These show the proportion of Odo’s estate in each of the twenty-two counties in which he held lands, and illustrate: the distribution of the total hidage; the value of the total hidage; the demesne hidage and the demesne value (the exact figures are listed in Tables 1 and 2). -

SMA 1983.Pdf

ii66 144 la COUNCIL FOR BRITISH ARCHAEOLOGY REGIONAL GROUP 9 (Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire) NEWSLETTER No.13 1983. SOUTH MIDLANDS ARCHAEOLOGY Editor: David Hall, Chairman: John Steane, Dept. of Archaeology, City & County Museum, University of Cambridge. Woodstock. lion.Sec.: Martin Petchey, Hon.Treas.: Dr. R.P. Hagerty, Milton Keynes Development 65 Camborne Avenue, 'Corporation, Aylesbury, Bradwell Abbey Field Centre, Bucks. HP21 7UE Bradwell, MILTON KEYNES. CONTENTS: Page EDITORIAL .. .. 1 BEDFORDSHIRE 2 BUCKINGHAMSHIRE .. .. 10 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE 15 UNITS AND INSTITUTIONS 42 Oxford University Department for External Studies , Rewley House, 3-7 Wellington Square, Oxford. ISBN 0308-2067 1 EDITORIAL After some delays it is with pleasure that the Executive Council present this volume of the Annual Newsletter. You will see that the title has been changed; we felt that although called a 'newsletter' the scope and content of our annual activities were much more like a journal than the name indicated, and altered the title accordingly. We hope that the changes will represent the beginning of a new era, rather than the end of an old one. Oxford University Department for External Studies, which has financed and produced all previous volumes of the Newsletter, will no longer be able to do so. This edition is the last that can be so financed, and Executive is grateful for all the help that.it has had over the years since the first issue in 1970, and for a generous gift of all the back numbers. We are now on our own. If members wish the Newsletter to continue and fulfil the useful task of promptly informing everyone about the latest work, then marathon efforts need to be made to sell copies. -

Deddington Castle

CSG Northampton Conference - Deddington Castle 1 acre Outer Bailey 8.5 acres Fig. 1. Plan of the castle as excavated by E M Jope, 1950. From Jope, E. M. and Threlfall, R. I., 1946-7, ‘Recent Mediaeval finds in the Oxford District’ Oxoniensia Vol. 11-12, pp. 167-8. Inset: Excavations in the late 1970s. The base of the tower on the Inner Bailey motte top. The SE corner looking toward the NW. Deddington Castle century once stone-walled enclosure castle. The Summary: monument is situated immediately east of the The motte and bailey castle and the later stone present village of Deddington. It occupies an enclosure castle at Deddington survive as extant east-facing spur overlooking a shallow valley earthworks on the eastern edge of the village through which a spring-fed stream flows from whose development it both promoted and then north to south. later affected. Each phase is a good example of Detail: its type, and part excavation has demonstrated The low motte and its western bailey survive as that both phases contain archaeological and an impressive group of earthworks, with the environmental remains relating to the monument, enclosure castle built into the north east corner. the landscape in which it was built and the The latter remains visible as a series of low economy of the inhabitants. The central part of banks and hollows within an enclosing ditch. To the site is in the care of the Secretary of State and the east, a second bailey, which encloses a the west outer bailey forms a public amenity used number of platforms and extends down to the and looked after by the villagers. -

Notes and News

Notes and News ARCHAEOLOGICAL NOTES, 1951 A . PREHISTORIC, ROMAN AND SAXON Bampum, Oxon. Mr. F. W. Shallcross reported the discovery of sherds of Romano-British coarse pottery and one fragment ofSarnian ware (Drag. Form 18/3 1) during building operations in the village. The site has since been concreted in. Cassingwn, Oxon. (Smith's Pit II. Nat. Grid 42/450099.) A fragment of tusk and a tooth of mammoth were dredged from the clay underlying the gravel, and presented to the Department of Geology together with similar past finds from this pit. An Anglo-Saxon iron spearhead, with traces of the wooden shaft in the socket was found in top-soil. It is in the Ashmolean Museum (1951.126). FIG. 17 COMPTON BEAUCHAMP, BERKS. Sherds of Iron Age A :2 pottery from Knighton Hill (p. 80) Scale: i In June and July, Mr. H.J. Case and Mr.J. H. Hedgelyexcavated the area of the gap in the big enclosure-ditch (PL. IX, A, and see Oxonimsia, VIl, 106-7) leading to the ford over the Evenlode just downstream from the present mill. There was no made-up road or any gate structure. Finds in the lowest filling of the ditches, besides the contracted burials of a woman and a child, included a few pieces of the latest non-Belgic local Iron Age pottery; stratified above was Belgic pottery. Then came Late Belgic corresponding to some of the finds from Alchester; this layer was post·conquest, and represented a prosperous period with plentiful food refuse. Above was 2nd-century Roman, and finally 2nd- and 3rd-century Roman pottery. -

Number Fifteen, 2000

THE JOURNAL OF THE WYCHWOODS LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY Number Fifteen, 2000 WYCHWOODS LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY Contents Foreword Foreword 3 The year 2000 seems an appropriate time for the Wychwoods Local History Society to hold an exhibition, Wychwood 2000, and celebrate the A Survey of the Earthworks at Ascott d'Oilly Castle 4 end of one millennium and the start of the next. The theme of Wychwood 2000 and this journal, timed to coincide with the exhibition, is continuity A Wychwoods Farming Year 1854–55 36 and change. The articles included are intended to complement the displays. A thousand years ago England as a state was in its infancy and the first Shipton and Religion in the Sixteenth Century 43 comprehensive written references to the Wychwood Forest and its associated villages is in the Domesday Survey. Much can also be learnt Medieval Pottery in the Wychwoods 51 from the scattering of debris left by the medieval villagers as they went about their domestic and farming life. Members of the Society have taken The Burford to Banbury Turnpike Road 55 part in much field-walking over the years and we are pleased to publish an integrated analysis. Members have also helped James Bond survey several The Wychwoods Manors in Domesday Book 65 sites of archaeological interest around the Wychwood villages and in October 1999 surveyed the humps and bumps by Ascott D’Oilly castle at What’s in a Name 72 Ascott manor. The results of the survey, published here, show this site to have been the most important that we have surveyed, and representative The Society’s Publications 77 of a generally understudied class of site. -

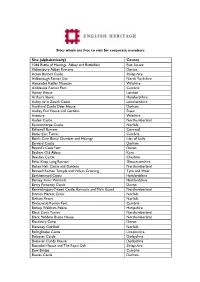

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and -

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are FREE TO VISIT for Corporate Members Opening times vary, pre-booking may be required, please check English Heritage website for details. Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Appuldurcombe House Isle of Wight Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham d's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blackfriars, Gloucester Gloucestershire Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire 1 Boscobel House and The -

St George's College, Windsor Castle, in the Late- Fifteenth and Early

St George’s College, Windsor Castle, in the Late- Fifteenth and Early-Sixteenth Centuries Euan Cameron Roger Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London, September 2015 Department of History, Royal Holloway, University of London 1 I, Euan Cameron Roger, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Euan Cameron Roger Signed: Date: 2 Abstract This thesis examines the royal college of St George, Windsor Castle, in the late- fifteenth and early-sixteenth centuries. The thesis considers specific groups of individuals within the college, including canons, vicars, clerks and poor knights that resided within, and assesses how these groups interacted with one another. This discussion includes problems of individual wages, the college’s collective income, personal interactions and liturgical change. The thesis provides a community study of the college, and questions the extent to which St George’s was a coherent community. It argues that the college was a distinctive institution, which was able to adapt as fashions changed, but which was not perfect. The thesis makes use of the college’s extensive medieval archive at Windsor, supported by manuscripts from The National Archives and other repositories, and fills a substantial gap in the historiography of the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century college. After setting out the college’s fourteenth-century foundations and historiography, five chapters consider different groups within the community. Chapters 1 and 2 investigate the secular canons who ran the college under the supervision of the dean or warden. -

Castles – English Midlands

Castles – English Midlands ‘Build Date’ refers to the oldest surviving significant elements In column 1; B ≡ Bedfordshire, BU ≡ Buckinghamshire, D ≡ Derbyshire, LC ≡ Leicestershire, NR ≡ Northamptonshire, NT ≡ Nottinghamshire, O ≡ Oxfordshire, R ≡ Rutland, ST ≡ Staffordshire WA ≡ Warwickshire, WO ≡ Worcestershire Occupation B Castle Location Configuration Build Date Current Remains Status 1 Someries TL 119 201 Fortified house c1450 Empty, early-18th C Ruined gatehouse & chapel BU 1 Boarstall SP 623 142 Fortified house 1312 Demolished, 1777 Gatehouse occupied as residence D 1 Bolsover SK 471 707 Enclosure + keep Early-12th C Occupied 17th C buildings, some ruined 2 Codnor SK 434 500 Enclosure 14th C Empty, 17th C Scattered ruins of walls & a chamber block 3 Haddon SK 235 664 Fortified house 1190s Occupied Entire, largely unmodified 4. Horston SK 376 432 Tower 12th C Empty, 15th C Fragmentary ruins 5 Mackworth SK 311 378 Fortified house 15th C Empty, 17th C Nothing but high ruin of gatehouse 6 Peveril SK 149 826 Enclosure Late-11th C Empty, c1400 Ruined keep, walls, foundations 7 Wingfield Manor SK 374 547 Fortified house 1439 Empty, 17th C Extensive ruins, especially inner court LC 1 Ashby SK 361 166 Fortified house c1150 Empty, 17th C High ruins of towers 2 Kirby Muxloe SK 524 026 Enclosure 1480 Empty, 17th C High ruins, tower & gatehouse 3 Leicester SK 583 041 Motte & bailey 1068 Part occupied Motte, hall, gatehouses in some form NR 1 Barnwell TL 049 852 Enclosure c1266 Empty, 17th C High ruins of walls, towers, & gatehouse 2 Fotheringhay