Cake & Cockhorse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Service 488: Chipping Norton - Hook Norton - Bloxham - Banbury

Service 488: Chipping Norton - Hook Norton - Bloxham - Banbury MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS Except public holidays Effective from 02 August 2020 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 489 Chipping Norton, School 0840 1535 Chipping Norton, Cornish Road 0723 - 0933 33 1433 - 1633 1743 1843 Chipping Norton, West St 0650 0730 0845 0940 40 1440 1540 1640 1750 1850 Over Norton, Bus Shelter 0654 0734 0849 0944 then 44 1444 1544 1644 1754 - Great Rollright 0658 0738 0853 0948 at 48 1448 1548 1648 1758 - Hook Norton Church 0707 0747 0902 0957 these 57 Until 1457 1557 1657 1807 - South Newington - - - - times - - - - - 1903 Milcombe, Newcombe Close 0626 0716 0758 0911 1006 each 06 1506 1606 1706 1816 - Bloxham Church 0632 0721 0804 0916 1011 hour 11 1511 1611 1711 1821 1908 Banbury, Queensway 0638 0727 0811 0922 1017 17 1517 1617 1717 1827 1914 Banbury, Bus Station bay 7 0645 0735 0825 0930 1025 25 1525 1625 1725 1835 1921 SATURDAYS 488 488 488 488 488 489 Chipping Norton, Cornish Road 0838 0933 33 1733 1833 Chipping Norton, West St 0650 0845 0940 40 1740 1840 Over Norton, Bus Shelter 0654 0849 0944 then 44 1744 - Great Rollright 0658 0853 0948 at 48 1748 - Hook Norton Church 0707 0902 0957 these 57 Until 1757 - South Newington - - - times - - 1853 Milcombe, Newcombe Close 0716 0911 1006 each 06 1806 - Bloxham Church 0721 0916 1011 hour 11 1811 1858 Banbury, Queensway 0727 0922 1017 17 1817 1904 Banbury, Bus Station bay 7 0735 0930 1025 25 1825 1911 Sorry, no service on Sundays or Bank Holidays At Easter, Christmas and New Year special timetables will run - please check www.stagecoachbus.com or look out for seasonal publicity This timetable is valid at the time it was downloaded from our website. -

English Heritage Og Middelalderborgen

English Heritage og Middelalderborgen http://blog.english-heritage.org.uk/the-great-siege-of-dover-castle-1216/ Rasmus Frilund Torpe Studienr. 20103587 Aalborg Universitet Dato: 14. september 2018 Indholdsfortegnelse Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Indledning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Problemstilling ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Kulturarvsdiskussion ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Diskussion om kulturarv i England fra 1980’erne og frem ..................................................................... 5 Definition af Kulturarv ............................................................................................................................... 6 Hvordan har kulturarvsbegrebet udviklet sig siden 1980 ....................................................................... 6 Redegørelse for Historic England og English Heritage .............................................................................. 11 Begyndelsen på den engelske nationale samling ..................................................................................... 11 English -

Chapter 3: the Finds

Chapter 3: The Finds THE MEDIEVAL AND POST-MEDIEVAL A draft report on the pottery from the 1984 POTTERY (FIGS 3.1-11) excavations was written by Maureen Mellor in the by Cathy Keevill 1980s. The primary aim of the further analysis was to refine the site chronology and to understand the Summary development of the site. This involved adding in the An assemblage of 6779 sherds was recovered from pottery recovered from the 1988-1991 excavations, stratified contexts. The majority of these (a total of amending the context dates derived from the assoc 6317 or 93%) were medieval. This is the first iated pottery where necessary, and checking on the stratified sequence from Witney and as such is dating for the main types within the assemblage in highly important for the understanding of the order to establish a chronology that would corres development of 12th-century and early-13th-century pond to the Oxfordshire pottery sequence. Under pottery traditions in West Oxfordshire. The most standing the development of the major local fabric interesting feature of the assemblage was the range and vessel traditions in west Oxfordshire was also a of imported material from other regions, particularly priority, especially the calcareous gravel-tempered south-western England. These included fabric types fabric (Witney Fabric 1), which is similar to types in from Minety, Wiltshire (Fabrics 9 and 37), from the Cotswolds (Mellor 1994,72) and at Oxford (fabric Laverstock, south Wiltshire (Fabrics 5 and 25), types OXAC). known in Bath and Trowbridge (fabric 23), Newbury The analysis also included a consideration of the (Fabrics 2 and 3), Winchester (Fabric 8), and a status of the site (and of different areas within the possible Nash Hill product (Fabric 33). -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

2018 PPP FINAL COMPLETE , Item 120

Oxfordshire County Council Pupil Place Plan 2018-2022 November 2018 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 3 2. SCHOOL ORGANISATION CONTEXT ................................................................ 4 2.1 Oxfordshire’s education providers ...................................................................... 4 Early education ............................................................................................. 4 Primary education ......................................................................................... 4 Secondary education .................................................................................... 5 Specialist education ...................................................................................... 5 2.2 Policies and legislation ....................................................................................... 6 Early education and childcare sufficiency ..................................................... 6 School places - local authorities’ statutory duties .......................................... 7 Policy on spare school places ....................................................................... 7 Special Educational Needs & Disabilities (SEND)......................................... 8 Academies in Oxfordshire ............................................................................. 9 Oxfordshire Education Strategy .................................................................. 10 2.3 -

Special Meeting of Council

Public Document Pack Special Meeting of Council Tuesday 27 January 2015 Members of Cherwell District Council, A special meeting of Council will be held at Bodicote House, Bodicote, Banbury, OX15 4AA on Tuesday 27 January 2015 at 6.30 pm, and you are hereby summoned to attend. Sue Smith Chief Executive Monday 19 January 2015 AGENDA 1 Apologies for Absence 2 Declarations of Interest Members are asked to declare any interest and the nature of that interest which they may have in any of the items under consideration at this meeting. 3 Communications To receive communications from the Chairman and/or the Leader of the Council. Cherwell District Council, Bodicote House, Bodicote, Banbury, Oxfordshire, OX15 4AA www.cherwell.gov.uk Council Business Reports 4 Cherwell Boundary Review: Response to Local Government Boundary Commission for England Draft Recommendations (Pages 1 - 44) Report of Chief Executive Purpose of report To agree Cherwell District Council’s response to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s (“LGBCE” or “the Commission”) draft recommendations of the further electoral review for Cherwell District Council. Recommendations The meeting is recommended: 1.1 To agree the Cherwell District Council’s response to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s draft recommendations of the further electoral review for Cherwell District Council (Appendix 1). 1.2 To delegate authority to the Chief Executive to make any necessary amendments to the council’s response to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s draft recommendations of the further electoral review for Cherwell District Council prior to submission in light of the resolutions of Council. -

The Warriner School

The Warriner School PLEASE CAN YOU ENSURE THAT ALL STUDENTS ARRIVE 5 MINUTES PRIOR TO THE DEPARTURE TIME ON ALL ROUTES From 15th September- Warriner will be doing an earlier finish every other Weds finishing at 14:20 rather than 15:00 Mon - Fri 1-WA02 No. of Seats AM PM Every other Wed 53 Sibford Gower - School 07:48 15:27 14:47 Burdrop - Shepherds Close 07:50 15:25 14:45 Sibford Ferris - Friends School 07:53 15:22 14:42 Swalcliffe - Church 07:58 15:17 14:37 Tadmarton - Main Street Bus Stop 08:00 15:15 14:35 Lower Tadmarton - Cross Roads 08:00 15:15 14:35 Warriner School 08:10 15:00 14:20 Heyfordian Travel 01869 241500 [email protected] 1-WA03/1-WA11 To be operated using one vehicle in the morning and two vehicles in the afternoon Mon - Fri 1-WA03 No. of Seats AM PM Every other Wed 57 Hempton - St. John's Way 07:45 15:27 14:42 Hempton - Chapel 07:45 15:27 14:42 Barford St. Michael - Townsend 07:50 15:22 14:37 Barford St. John - Farm on the left (Street Farm) 07:52 15:20 14:35 Barford St. John - Sunnyside Houses (OX15 0PP) 07:53 15:20 14:35 Warriner School 08:10 15:00 14:20 Mon - Fri 1-WA11 No. of Seats AM PM Every other Wed 30 Barford St. John 08:20 15:35 15:35 Barford St. Michael - Lower Street (p.m.) 15:31 15:31 Barford St. -

Appendix 1 , Item 63. PDF 204 KB

Appendix 1 Ward Polling Polling Place Address District Adderbury CAA1 The Institute, The Green, Adderbury CAA1 The Institute, The Green, Adderbury CCR1 The Meeting Room, Manor Farm, Milton Ambrosden CAB1 Ambrosden Village Hall, Ambrosden & Chesterton CBS1 Chesterton Village Hall, Alchester Road, Chesterton CBS2 Chesterton Village Hall, Alchester Road, Chesterton CCP1 Middleton Stoney Village Hall, Heyford Road, Middleton Stoney CDN1 Wendlebury Village Hall, Main Street, Wendlebury Banbury CAE1 Mobile Station @ Morrisons Car Park, Banbury Calthorpe CAF1 Chasewell Community Centre, Avocet Way, Banbury CAF1 Chasewell Community Centre, Avocet Way, Banbury Banbury CAG1 The Peoples Church, Horsefair, Banbury Easington CAH1 Easington Methodist Church Hall, Grange Road, Banbury CAH1 Easington Methodist Church Hall, Grange Road, Banbury CAH2 Harriers Banbury Academy, Bloxham Road, Banbury CAJ2 Harriers Banbury Academy, Bloxham Road, Banbury CAI1 Harriers Banbury Academy, Bloxham Road, Banbury CAI3 Queensway Primary School, Queensway, Banbury CAJ1 Queensway Primary School, Queensway, Banbury CAJ1 Queensway Primary School, Queensway, Banbury Banbury CAK1 St Leonards Church, Middleton Road, Banbury Grimsbury & Castle CAK1 St Leonards Church, Middleton Road, Banbury CAL1 Grimsbury Community Hall, 2 Burchester Place, Banbury CAM1 East Street Centre, Calder Close, Banbury CAM1 East Street Centre, Calder Close, Banbury Banbury CAN1 St Mary`s School, Southam Road, Banbury Grimsbury & Castle CAO1 Banbury Methodist Church, Marlborough Road, Banbury (cont..) CAO2 St Johns Church, South Bar, Banbury Banbury CAP1 Hillview County Primary School, Hillview Crescent, Banbury Hardwick CAQ1 Hardwick Community Centre, Ferriston, Banbury CAQ1 Hardwick Community Centre, Ferriston, Banbury CAR1 Hanwell Fields Community Centre, Rotary Way, Hanwell Fields, Banbury CAR1 Hanwell Fields Community Centre, Rotary Way, Hanwell Fields, Banbury Banbury CAS1 St. -

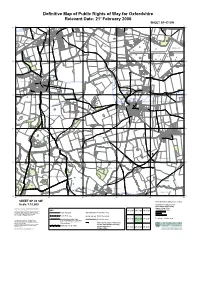

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 43 SW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 43 SW 40 41 42 43 44 45 2800 3500 5900 7300 5300 8300 Pond 0006 0003 5400 0004 5400 0004 5800 0004 A 361 1400 35 Pond 35 Ryehill Barn CLOSE Church Farm 136/9 Factory MANNING 29 Brooklands House Water 8/4a Pond 136/4 Pond 8700 Oak View 8/2 Pavilion 300/7 3587 Drain Happy Valley Farm Milcombe 5800 House Brookside 29 4885 5385 The Cottage Little Stoney 2083 FERNHILL WAY 5783 Hillcroft Laburnum Farnell Fields Hall Farm Milcombe GASCOIGNE House Sallivon Hall BLOXHAM ROAD GASCOIGNE CL 4381 300/2 7380 PAR 298/4 Coombe ADISE LANE Smithy House PO Cottage WAY WAY GASCOIGNE CLOSE Sinks Gleemeade 0080 Smithy Stone Leigh MAULE 0080 Fieldside 8679 1978 Drain Issues BLOXHAM ROAD Bovey The Brompton Farm 3675 Old Barn Pippins 8274 Lea 3774 300/7 Dovecot Manor Manor Ct Drain HORTON LANE Pond Farm Pond 8876 TON ROAD 6872 NG CHURCH LANE Well 5772 SOUTH NEWI BARLOW CL Pond Hall Farm Cotts Reemas Southwynd 3169 Farm 298/9 8068 View 3767 0066 0067 Baytree 1267 298/3 Heath Villa Pond Pond House 0066 Broad Hill View Cottage 2364 Hollies Barn Sinks Horse and Groom (PH) 4560 Jasmine Oak GREEN THE Cottage Hall Farm Houses Council The Old Arnsby Cott 2757 PORTLAND ROAD Spring Pp Ho Mulberry Issues Milcombe CP Arnsby Keytes Cottage St Laurence's Church Blue Pitts BARFORD ROAD HEATH CLOSE Rosery Kingstone Holly Cottage Cottage Westfield Cottag 0049 Slade Farm Rye House Redford House Little Heritage 298/7a e 1152 0052 1650 Birchells Barn 0650 298/8 Pond Ppg Sinks -

The United Benefice of Bloxham with Milcombe and South Newington Benefice Profile Autumn 2015 TABLE of CONTENTS

The United Benefice of Bloxham with Milcombe and South Newington Benefice Profile Autumn 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS: FOREWORD FROM THE BISHOP 1 APPENDICES BENEFICE OVERVIEW 2 APPENDIX 1 - OUR LOCATION 15 WHAT WE ARE PRAYING FOR 3 APPENDIX II - BENEFICE SUNDAY SERVICES 16 PARISH PROFILES APPENDIX III - OUR FINANCES 17 BLOXHAM 4 MILCOMBE 7 SOUTH NEWINGTON 9 OUR SCHOOLS 11 THE VICARAGE 12 WHAT WE CAN OFFER 13 THE DEDDINGTON DEANERY 14 FOREWORD BY RT REVD. COLIN FLETCHER, BISHOP OF DORCHESTER one and the Archdeacon, Parish Development Adviser, and I will, as ever, do what we can to offer our help to you. It is good to be proved wrong as a bishop. I warmly commend this post to you. Normally I look to move things on in a vacancy to make sure that it does not last too long. After all longer ones can damage the life of a benefice. Bloxham, Milcombe and South Newington are, however, an exception to that general rule. It took courage not to appoint when we had a chance to do so, but the result has been, to quote this profile, ‘A realisation that the Holy Spirit (has been) at work during the vacancy drawing out the talents, resources, and skill sets amongst the congregations and lay leadership of the benefice’. Looking back, these months have been a period of growth and development in the life of these congregations. This post has always been a good one with plenty of opportunities for development in one way or another, but it is an even better one now. -

Oxfordshire. Far 365

TRADES DIRECTORY.] OXFORDSHIRE. FAR 365 Chesterman Richard Austin, Cropredy Cottrell Richard, Shilton, Faringdon Edden Charles, Thame lawn, Cropredy, Leamington Cox: Amos,East end,North Leigb,Witney Edden William, 54 High street, Thame ChichesterW.Lwr.Riding,N.Leigh,lHny Cox: Charles, Dnnsden, Reading Eden James, Charlbury S.O Child R. Astley bridge, Merton, Bicester Cox: Charles, Kidmore, Reading Edginton Charles, Kirtlington, Oxford Chi!lingworth Jn. Chippinghurst,Oxford Cox: Mrs. Eliza, Priest end, Thame Edginton Henry Bryan, Upper court, Chillingworth John, Cuddesdon, Oxford Cox: Isaac, Standhill,Henley-on-Thames Chadlington, Charlbury S.O Chillingworth J. Little Milton, Tetswrth Cox: :!\Irs. Mary, Yarnton, Oxford Edginton William, Merris court, Lyne- ChiltonChs.P.Nethercote,Tackley,Oxfrd Cox Thomas, Horton, Oxford ham, Chipping Norton Chown Brothers, Lobb, Tetsworth Cox Thos. The Grange,Oddington,Oxfrd Edmans Thos. Edwd. Kingsey, Thame Chown Mrs. M. Mapledurham, Reading Cox William, Horton, Oxford Edmonds Thomas Henry, Alvescott S. 0 Cho wn W. Tokers grn. Kid more, Reading Craddock F. Lyneham, Chipping "N orton Ed wards E. Churchill, Chipping N orton Churchill John, Hempton, Oxford CraddockFrank,Pudlicot,Shortbampton, Edwards William, Ramsden, Oxford Churchill William, Cassington, Oxford Charlbury S.O Eeley James, Horsepath, Oxford Clack Charles, Ducklington, Witney Craddock John W. Kencott, Swindon Eggleton Hy. David, Cbinnor, Tetswrth Clack William, Minster Lovell, Witney Craddock R. OverKiddington,Woodstck Eggleton John, Stod:.enchurch, Tetswrth Clapham C.Kencott hill,Kencott,Swindn Craddock William, Brad well manor, Eldridge John, Wardington, Banbury Clapton G. Osney hl.N orthLeigh, Witney Brad well, Lechlade S. 0 (Gloucs) Elkingto::1 Thos. & Jn. Claydon, Banbry Clapton James, Alvescott S.O Crawford Joseph, Bletchington, Oxford Elliott E. -

'Income Tax Parish'. Below Is a List of Oxfordshire Income Tax Parishes and the Civil Parishes Or Places They Covered

The basic unit of administration for the DV survey was the 'Income tax parish'. Below is a list of Oxfordshire income tax parishes and the civil parishes or places they covered. ITP name used by The National Archives Income Tax Parish Civil parishes and places (where different) Adderbury Adderbury, Milton Adwell Adwell, Lewknor [including South Weston], Stoke Talmage, Wheatfield Adwell and Lewknor Albury Albury, Attington, Tetsworth, Thame, Tiddington Albury (Thame) Alkerton Alkerton, Shenington Alvescot Alvescot, Broadwell, Broughton Poggs, Filkins, Kencot Ambrosden Ambrosden, Blackthorn Ambrosden and Blackthorn Ardley Ardley, Bucknell, Caversfield, Fritwell, Stoke Lyne, Souldern Arncott Arncott, Piddington Ascott Ascott, Stadhampton Ascott-under-Wychwood Ascott-under-Wychwood Ascot-under-Wychwood Asthall Asthall, Asthall Leigh, Burford, Upton, Signett Aston and Cote Aston and Cote, Bampton, Brize Norton, Chimney, Lew, Shifford, Yelford Aston Rowant Aston Rowant Banbury Banbury Borough Barford St John Barford St John, Bloxham, Milcombe, Wiggington Beckley Beckley, Horton-cum-Studley Begbroke Begbroke, Cutteslowe, Wolvercote, Yarnton Benson Benson Berrick Salome Berrick Salome Bicester Bicester, Goddington, Stratton Audley Ricester Binsey Oxford Binsey, Oxford St Thomas Bix Bix Black Bourton Black Bourton, Clanfield, Grafton, Kelmscott, Radcot Bladon Bladon, Hensington Blenheim Blenheim, Woodstock Bletchingdon Bletchingdon, Kirtlington Bletchington The basic unit of administration for the DV survey was the 'Income tax parish'. Below is