Naıve Encounters with Chimpanzees in the Goualougo Triangle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Ape Conservation Fund Grants

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, International Affairs Division of International Conservation CFDA 15.629 Multinational Species Conservation Fund – Great Apes Program Summary of Projects 2006 58 Grants Total FWS Funding: $3,881,585* Total Leveraged Funds: $4,773,148 Strengthening Local Capacity to Conserve the Western Black Crested Gibbon, Vietnam. In partnership with Fauna and Flora International. This project will support on the job training of government and management board personnel and the provision of specialized training in basic management and administrative skills. As a result, local Vietnamese officials will assume greater responsibility for management, administration, and fund raising for the Hoang Lien Mountains gibbon conservation program. FWS: $44,977. Leveraged Funds: $52,740. Conservation and Management of Hoolock Gibbons: Capacity Building, Habitat Restoration, and Translocation, Bangladesh. In partnership with Department of Zoology, University of Dhaka. This project will improve the capacity of the Forest Department to monitor, study, and protect hoolock gibbons; improve conservation awareness of people living around important habitats; initiate planting of indigenous tree species important for gibbon food and cover in protected area habitats; and initiate translocation of gibbons remaining in highly degraded, fragmented habitats. FWS: $49,495. Leveraged Funds: $33,600. Green Bridges: Reconnecting Fragmented Ape Habitat in Southern Sumatra through Forest Rehabilitation and Wildlife Friendly Agroforestry, Indonesia. In -

Chimpanzees Prey on Army Ants with Specialized Tool Set

American Journal of Primatology 72:17–24 (2010) RESEARCH ARTICLE Chimpanzees Prey on Army Ants with Specialized Tool Set 1,2Ã 3,4 5,6 CRICKETTE M. SANZ , CASPAR SCHO¨ NING , AND DAVID B. MORGAN 1Department of Primatology, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany 2Department of Anthropology, Washington University, Saint Louis, Missouri 3Department of Biology, Centre of Social Evolution, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark 4Honey Bee Research Institute, Friedrich-Engels-Strasse, Hohen Neuendorf, Germany 5Lester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes, Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, Illinois 6Wildlife Conservation Society, Congo Program, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo Several populations of chimpanzees have been reported to prey upon Dorylus army ants. The most common tool-using technique to gather these ants is with ‘‘dipping’’ probes, which vary in length with regard to aggressiveness and lifestyle of the prey species. We report the use of a tool set in army ant predation by chimpanzees in the Goualougo Triangle, Republic of Congo. We recovered 1,060 tools used in this context and collected 25 video recordings of chimpanzee tool-using behavior at ant nests. Two different types of tools were distinguished based on their form and function. The chimpanzees use a woody sapling to perforate the ant nest, and then a herb stem as a dipping tool to harvest the ants. All of the species of ants preyed upon in Goualougo are present and consumed by chimpanzees at other sites, but there are no other reports of such a regular or widespread use of more than one type of tool to prey upon Dorylus ants. -

E-News, Web Sites, and Social Media

70 / Connections: E-news, Web Sites, and Social Media Connections: E-News, Web Sites, and Social Media Africa Biodiversity Collaborative Group Cameroon Primatological Society Website: www.abcg.org Twitter: twitter.com/Camer_primates Facebook: facebook.com/ABCGconserve Twitter: twitter.com/ABCGconserve Canadian-Cameroon Ape Network Facebook: facebook.com/cancamapenetwork/ African Primates (for journal and group) Twitter: twitter.com/CanCamApeNetwrk Website: primate-sg.org/african_primates/ Facebook: facebook.com/groups/AfricanPrimates/ Centre de Conservation pour Chimpanzes Twitter: twitter.com/africanprimates Website: www.projetprimates.com/en/ Facebook: facebook.com/ African Primatological Society CentreDeConservationPourChimpanzes Facebook: facebook.com/African.Primatological. Twitter: twitter.com/projectprimate Society/ Twitter: twitter.com/AfricanPs Chimp Eden (JGI Sanctuary, South Africa) Website: www.chimpeden.com/ African Wildlife Foundation Facebook: facebook.com/JGISA Website: www.awf.org Twitter: twitter.com/jgisachimpeden Facebook: facebook.com/AfricanWildlifeFoundation Twitter: twitter.com/AWF_Official Chimpanzee Sanctuary & Wildlife Conservation Trust (Ngamba Island) Amboseli Baboons Website: www.ngambaisland.org/ Website: www.amboselibaboons.nd.edu E-newsletter contact: [email protected] Facebook: facebook.com/Amboseli-Baboon-Research- Facebook: facebook.com/ngambaisland Project-296131010593283 Twitter: twitter.com/ngambaisland Twitter: twitter.com/AmboseliBaboons Colobus Conservation Barbary Macaque Awareness and Conservation -

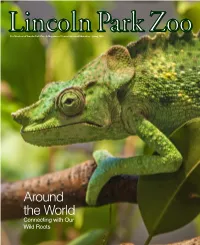

Around the World

For Members of Lincoln Park Zoo · A Magazine of Conservation and Education · Spring 2016 Around the World Connecting with Our Wild Roots DEPARTMENTS IN THIS ISSUE Perspective Volume 15, Number 1 · For Members of Lincoln Park Zoo 1 President and CEO Kevin Bell highlights how zoos around the globe connect visitors with wildlife—and are increasingly working together to save it. 16 Plant Provenance Native and exotic species share space in the zoo’s gardens, where horticulturists aim for interest in all four seasons. 18 News of the Zoo Chimpanzee close-ups, updates on new zoo buildings and a look back at the brilliance of ZooLights Present- ed By ComEd and PowerShares QQQ. 19 Wild File Baby monkeys stand out, snowy species head out- FEATURES doors and the zoo animal hospital makes a move. 2 Wild City 20 Membership Matters You might think the “Chicago ecosystem” offers few Save the date for Members-Only Morning, SuperZoo- surprises, but zoo scientists are spotting plenty of Picnic and a summer series of member tours. unexpected wildlife in this urban range. 21 Calendar 4 Climbing the Canopy Step into spring with fun zoo events, including our Monkeys skitter, jaguars prowl and sloths…stay put new Food Truck Social! as we take a trip up into the canopy of the South American rainforest. Continue Your Visit Online Visit lpzoo.org for Lincoln Park Zoo photos, videos Where Rainforest Still Rules and up-to-date info on events and animals. You can 6 also find us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram! The wilds of the Goualougo Triangle are one of the most pristine places on Earth, a zoo study site and an We'd Like to Hear from You! Send your feedback on this issue of untouched home for gorillas and chimpanzees. -

Great Ape Conservation Fund Grants, 2003

DIVISION OF INTERNATIONAL CONSERVATION GREAT APES CONSERVATION FUND SUMMARY OF GRANTS 2004 The Yellow-cheeked Crested Gibbons (Nomascus gabriellae) of Cat Tien National Park: Assessing Their Status, and Increasing Their Conservation Profile in the Local Community, Vietnam. In partnership with Cat Tien National Park. FWS: $21,500. Leveraged funds: $8,061. To include developing recommendations for the management of gibbons and their habitat; and activities to raise local peoples awareness of the need to reduce human impact on the gibbons and their habitat. A National Survey of Pileated Gibbons (Hylobates pileatus) to Identify Their Current status, Viable Populations and Recommendations for Their Long-term Conservation, Thailand. In partnership with WWF-Thailand. FWS: $27,075. Leveraged funds: $12,605. This will allow comparison of current data on the species status in the country with that of an earlier study to determine the population’s trend. Orangutan Conservation and Habitat Protection in Gunung Palung National Park, Indonesia. In partnership with The President and Fellows of Harvard College. FWS: $50,000. Leveraged funds: $109,250. To raise public awareness on forest and orangutan conservation in the park through school presentations and field trips, initiate development of an environmental education center, train local guides and interpreters, implement an awareness campaign on illegal logging, produce a film on the park for presentation to local people, and develop and implement a habitat protection plan. Orangutan Protection and Monitoring Unit, Indonesia. In partnership with Fauna and Flora International. FWS: $49,970. Leveraged funds: $5,560. Continue support of three-four person Orangutan Protection and Monitoring Units to protect orangutan and their habitat at Gunung Palung National Park and its surrounding buffer zone. -

E-News, Web Sites, and Social Media

78 / Connections: E-news, Web Sites, and Social Media Connections: E-News, Web Sites, and Social Media Africa Biodiversity Collaborative Group Centre de Conservation pour Chimpanzes Website: www.abcg.org Website: http://www.projetprimates.com/en/ E-newsletter contact: [email protected] Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ Facebook: www.facebook.com/ABCGconserve CentreDeConservationPourChimpanzes Twitter: http://twitter.com/ABCGconserve Chimp Eden (JGI Sanctuary, South Africa) African Primates (for journal and group) Website: http://www.chimpeden.com/ Website: www.primate-sg.org/african_primates/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/jgisachimpeden Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/ AfricanPrimates/ Chimpanzee Sanctuary & Wildlife Conservation Trust Twitter: http://twitter.com/africanprimates (Ngamba Island) Website: www.ngambaisland.com/ African Primatological Society E-newsletter contact: [email protected] Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/African. Facebook: www.facebook.com/ngambaisland Primatological.Society/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/AfricanPs Colobus Conservation Website: www.colobusconservation.org African Wildlife Foundation Facebook: www.facebook.com/pages/Colobus- Website: www.awf.org Conservation/137445029669543 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/Team_Colobus AfricanWildlifeFoundation Twitter: http://twitter.com/AWF_Official Conservation through Public Health E-newsletter contact: [email protected] Amboseli Baboons Facebook: Conservation Through Public Health Website: www.amboselibaboons.nd.edu -

Chimpanzee Tool Technology in the Goualougo Triangle, Republic of Congo

Journal of Human Evolution 52 (2007) 420e433 Chimpanzee tool technology in the Goualougo Triangle, Republic of Congo Crickette M. Sanz a,*, David B. Morgan b,c a Department of Primatology, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Deutscher Platz 6, 04103 Leipzig, Germany b Wildlife Conservation Society, Congo Program, B.P. 14537, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo c Lester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes, Lincoln Park Zoo, 2001 N. Clark Street, Chicago, IL 60614, U.S.A. Received 30 April 2006; accepted 8 November 2006 Abstract With the exception of humans, chimpanzees show the most diverse and complex tool-using repertoires of all extant species. Specific tool repertoires differ between wild chimpanzee populations, but no apparent genetic or environmental factors have emerged as definitive forces shaping variation between populations. However, identification of such patterns has likely been hindered by a lack of information from chimpanzee taxa residing in central Africa. We report our observations of the technological system of chimpanzees in the Goualougo Triangle, located in the Republic of Congo, which is the first study to compile a complete tool repertoire from the Lower Guinean subspecies of chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes troglodytes). Between 1999 and 2006, we documented the tool use of chimpanzees by direct observations, remote video monitoring, and collections of tool assemblages. We observed 22 different types of tool behavior, almost half of which were habitual (shown repeatedly by several individuals) or customary (shown by most members of at least one age-sex class). Several behaviors considered universals among chimpanzees were confirmed in this population, but we also report the first observations of known individuals using tools to perforate termite nests, puncture termite nests, pound for honey, and use leafy twigs for rain cover. -

PETITION Before the Fish and Wildlife Service United States Department

PETITION Before the Fish and Wildlife Service United States Department of the Interior March 16, 2010 To Upgrade Captive Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) from Threatened to Endangered Status Pursuant to the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as Amended Pan troglodytes (Photograph by National Geographic) Prepared by Anna Frostic, Esq. The Humane Society of the United States TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction………………………………………………….…….……….…........4 II. Legal Background………………….…………….………………………………...7 A. Endangered Species Act Background…..…………………………………...7 B. The Listing History of the Chimpanzee……..….…………………………15 III. Argument: Depriving Captive Chimpanzees of Full Protection Under the ESA is Antithetical to Conserving the Species……….………….….……….20 A. The ―Split-Listing‖ Scheme for Pan troglodytes has Contributed to a Proliferation of Privately Owned and Exploited Chimpanzees, Interfering With Conservation of the Species in the Wild..…………....27 1. Chimpanzees in Entertainment.…………………..……..…………....29 a. Chimpanzees Are Widely Exploited for Entertainment in the U.S…………………………………………………………………..29 b. Because Chimpanzees Are So Pervasively Used in Entertainment the Public Believes the Species is Prevalent in the Wild………………………………………………………....69 c. Chimpanzees Used in Entertainment Are Abused and Mistreated................................................................................71 2. Chimpanzees Used as Pets……………………………………………...77 3. Chimpanzees in Biomedical Research Laboratories………..…........87 B. Threats to Wild Chimpanzee Populations Have Only Increased -

Jane Goodall

Jane Goodall Dame Jane Goodall DBE Goodall in Tanzania in 2018 Born Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall 3 April 1934 (age 85) London, England, UK Alma mater Newnham College, Cambridge Darwin College, Cambridge Known for Study of chimpanzees, conservation, animal welfare Spouse(s) Hugo van Lawick (m. 1964; div. 1974) Derek Bryceson (m. 1975; died 1980) Children 1 Awards Kyoto Prize (1990) Hubbard Medal (1995) Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement (1997) DBE (2004) Scientific career Thesis Behaviour of free-living chimpanzees (1966) [1] Doctoral advisor Robert Hinde Influences Louis Leakey Jane Goodall's voice MENU 0:00 from the BBC programme Woman's Hour, 26 January 2010[2] Signature Dame Jane Morris Goodall DBE (/ˈɡʊdɔːl/; born Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall on 3 April 1934),[3] formerly Baroness Jane van Lawick-Goodall, is an English primatologist and anthropologist.[4] Considered to be the world's foremost expert on chimpanzees, Goodall is best known for her 60-year study of social and family interactions of wild chimpanzees since she first went to Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania in 1960.[5] She is the founder of the Jane Goodall Institute and the Roots & Shoots programme, and she has worked extensively on conservation and animal welfare issues. She has served on the board of the Nonhuman Rights Project since its founding in 1996.[6][7] In April 2002, she was named a UN Messenger of Peace. Dr. Goodall is also honorary member of the World Future Council. Early years Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall was born in 1934 in Hampstead, London,[8] to businessman Mortimer Herbert Morris-Goodall (1907–2001) and Margaret Myfanwe Joseph (1906–2000),[9] a novelist from Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire,[10] who wrote under the name Vanne Morris-Goodall.[3] The family later moved to Bournemouth, and Goodall attended Uplands School, an independent school in nearby Poole.[3] As a child, as an alternative to a teddy bear, Goodall's father gave her a stuffed chimpanzee named Jubilee. -

202004 Nouabale-Ndoki National Park Monthly Report APRIL2020.Pdf

NOUABALE-NDOKI NATIONAL PARK, APRIL 2020 The baby gorilla Kalle in the Goualogo forest ©S.Brogan/WCS SUMMARY o The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), the Congo Conservation Company (CCC) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), in partnership with the Congolese Government, are launching a new four-year program to develop ecotourism in Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park. You will now find a section dedicated to this program on page 2 of the monthly newsletter. o As part of the response to the coronavirus pandemic, the Foundation for the Tri-National Sangha (FTNS) made additional emergency funds available to the TNS protected areas officialized by an amendment to the PTAB 2020 validated by the FNN Board of Directors and which integrates two new activities related to specific actions against the spread of Covid-19. CONSERVATION AND BIODIVERSITY Patrol effort: NNNP arrests: Seizures: *in red, suspects transferred to local courts Illegally killed elephants: Hunting camp monitoring: camps camps 27 visited 26 destroyed *red indicates carcassed found within the park boundaries Anti-poaching Development and Support:Distribution of face masks to rangers and guards. New operational measures for anti-poaching operations were introduced during the COVID-19 lockdown. ARREST OF A SUSPECT AND SEIZURE OF 60 KG OF ELEPHANT PHOTO OF THE MONTH MEAT, IVORY AND TWO AUTOMATIC WEAPONS TO THE SOUTH OF THE PARK. WILDLIFE CRIME UNIT AVIATION PROGRAM - Reports of 24 wildlife trafficking / poaching Surveillance flights: 0 network activities. Logistics flights: 0 The situation remains unchanged for - Identification of 5 the Aviation Program. The arrival of traffickers/poachers not yet the new WCS-Congo pilot is listed in the database. -

Molecular Ecology and Natural History of Simian Foamy Virus Infection in Wild-Living Chimpanzees

Molecular Ecology and Natural History of Simian Foamy Virus Infection in Wild-Living Chimpanzees Weimin Liu1, Michael Worobey2, Yingying Li1, Brandon F. Keele1, Frederic Bibollet-Ruche1, Yuanyuan Guo1, Paul A. Goepfert1, Mario L. Santiago3, Jean-Bosco N. Ndjango4, Cecile Neel5,6, Stephen L. Clifford7, Crickette Sanz8, Shadrack Kamenya9, Michael L. Wilson10, Anne E. Pusey11, Nicole Gross-Camp12, Christophe Boesch8, Vince Smith13, Koichiro Zamma14, Michael A. Huffman15, John C. Mitani16, David P. Watts17, Martine Peeters5, George M. Shaw1, William M. Switzer18, Paul M. Sharp19, Beatrice H. Hahn1* 1 Departments of Medicine and Microbiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, United States of America, 2 University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, United States of America, 3 Gladstone Institute for Virology and Immunology, University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, California, United States of America, 4 Faculties of Sciences, University of Kisangani, Democratic Republic of Congo, 5 Institut de Recherche pour le De´veloppement (IRD) and University of Montpellier 1, Montpellier, France, 6 Projet Prevention du Sida ou Cameroun (PRESICA), Yaounde´, Cameroun, 7 Centre International de Recherches Medicales de Franceville (CIRMF), Franceville, Gabon, 8 Max-Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany, 9 Gombe Stream Research Centre, The Jane Goodall Institute, Tanzania, 10 Department of Anthropology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America, 11 Jane Goodall Institute’s -

Ticks, Hair Loss, and Non-Clinging Babies: a Novel Tick-Based Hypothesis for the Evolutionary Divergence of Humans and Chimpanzees

life Hypothesis Ticks, Hair Loss, and Non-Clinging Babies: A Novel Tick-Based Hypothesis for the Evolutionary Divergence of Humans and Chimpanzees Jeffrey G. Brown Independent Researcher, Saddle Brook, NJ 07663, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Human straight-legged bipedalism represents one of the earliest events in the evolutionary split between humans (Homo spp.) and chimpanzees (Pan spp.), although its selective basis is a mystery. A carrying-related hypothesis has recently been proposed in which hair loss within the hominin lineage resulted in the inability of babies to cling to their mothers, requiring mothers to walk upright to carry their babies. However, a question remains for this model: what drove the hair loss that resulted in upright walking? Observers since Darwin have suggested that hair loss in humans may represent an evolutionary strategy for defence against ticks. The aim of this review is to propose and evaluate a novel tick-based evolutionary hypothesis wherein forest fragmentation in hominin paleoenvironments created conditions that were favourable for tick proliferation, selecting for hair loss in hominins and grooming behaviour in chimpanzees as divergent anti-tick strategies. It is argued that these divergent anti-tick strategies resulted in different methods for carrying babies, driving the locomotor divergence of humans and chimpanzees. Keywords: forest fragmentation; parasites; last common ancestor; bipedalism; knuckle-walking; Citation: Brown, J.G. Ticks, Hair social grooming Loss, and Non-Clinging Babies: A Novel Tick-Based Hypothesis for the Evolutionary Divergence of Humans and Chimpanzees. Life 2021, 11, 435. 1. Introduction https://doi.org/10.3390/life11050435 The evolutionary split between humans (Homo spp.) and chimpanzees (Pan spp.) is generally agreed to have occurred in the equatorial rainforest of East Africa approximately Academic Editors: Koichiro Tamura 5–8 million years ago (Ma) [1–4].