Chimpanzee Tool Technology in the Goualougo Triangle, Republic of Congo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Primate Aesthetics

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2016 Primate Aesthetics Chelsea L. Sams University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Art Practice Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Sams, Chelsea L., "Primate Aesthetics" (2016). Masters Theses. 375. https://doi.org/10.7275/8547766 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/375 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRIMATE AESTHETICS A Thesis Presented by CHELSEA LYNN SAMS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS May 2016 Department of Art PRIMATE AESTHETICS A Thesis Presented by CHELSEA LYNN SAMS Approved as to style and content by: ___________________________________ Robin Mandel, Chair ___________________________________ Melinda Novak, Member ___________________________________ Jenny Vogel, Member ___________________________________ Alexis Kuhr, Department Chair Department of Art DEDICATION For Christopher. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am truly indebted to my committee: Robin Mandel, for his patient guidance and for lending me his Tacita Dean book; to Melinda Novak for taking a chance on an artist, and fostering my embedded practice; and to Jenny Vogel for introducing me to the medium of performance lecture. To the longsuffering technicians Mikaël Petraccia, Dan Wessman, and Bob Woo for giving me excellent advice, and tolerating question after question. -

Great Ape Conservation Fund Grants

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, International Affairs Division of International Conservation CFDA 15.629 Multinational Species Conservation Fund – Great Apes Program Summary of Projects 2006 58 Grants Total FWS Funding: $3,881,585* Total Leveraged Funds: $4,773,148 Strengthening Local Capacity to Conserve the Western Black Crested Gibbon, Vietnam. In partnership with Fauna and Flora International. This project will support on the job training of government and management board personnel and the provision of specialized training in basic management and administrative skills. As a result, local Vietnamese officials will assume greater responsibility for management, administration, and fund raising for the Hoang Lien Mountains gibbon conservation program. FWS: $44,977. Leveraged Funds: $52,740. Conservation and Management of Hoolock Gibbons: Capacity Building, Habitat Restoration, and Translocation, Bangladesh. In partnership with Department of Zoology, University of Dhaka. This project will improve the capacity of the Forest Department to monitor, study, and protect hoolock gibbons; improve conservation awareness of people living around important habitats; initiate planting of indigenous tree species important for gibbon food and cover in protected area habitats; and initiate translocation of gibbons remaining in highly degraded, fragmented habitats. FWS: $49,495. Leveraged Funds: $33,600. Green Bridges: Reconnecting Fragmented Ape Habitat in Southern Sumatra through Forest Rehabilitation and Wildlife Friendly Agroforestry, Indonesia. In -

Chimpanzees Prey on Army Ants with Specialized Tool Set

American Journal of Primatology 72:17–24 (2010) RESEARCH ARTICLE Chimpanzees Prey on Army Ants with Specialized Tool Set 1,2Ã 3,4 5,6 CRICKETTE M. SANZ , CASPAR SCHO¨ NING , AND DAVID B. MORGAN 1Department of Primatology, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany 2Department of Anthropology, Washington University, Saint Louis, Missouri 3Department of Biology, Centre of Social Evolution, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark 4Honey Bee Research Institute, Friedrich-Engels-Strasse, Hohen Neuendorf, Germany 5Lester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes, Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, Illinois 6Wildlife Conservation Society, Congo Program, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo Several populations of chimpanzees have been reported to prey upon Dorylus army ants. The most common tool-using technique to gather these ants is with ‘‘dipping’’ probes, which vary in length with regard to aggressiveness and lifestyle of the prey species. We report the use of a tool set in army ant predation by chimpanzees in the Goualougo Triangle, Republic of Congo. We recovered 1,060 tools used in this context and collected 25 video recordings of chimpanzee tool-using behavior at ant nests. Two different types of tools were distinguished based on their form and function. The chimpanzees use a woody sapling to perforate the ant nest, and then a herb stem as a dipping tool to harvest the ants. All of the species of ants preyed upon in Goualougo are present and consumed by chimpanzees at other sites, but there are no other reports of such a regular or widespread use of more than one type of tool to prey upon Dorylus ants. -

The Itombwe Massif, Democratic Republic of Congo: Biological Surveys and Conservation, with an Emphasis on Grauer's Gorilla and Birds Endemic to the Albertine Rift

Oryx Voi 33 No 4 October -.939 The Itombwe Massif, Democratic Republic of Congo: biological surveys and conservation, with an emphasis on Grauer's gorilla and birds endemic to the Albertine Rift llambu Omari, John A. Hart, Thomas M. Butynski, N. R. Birhashirwa, Agenonga Upoki, Yuma M'Keyo, Faustin Bengana, Mugunda Bashonga and Norbert Bagurubumwe Abstract In 1996, the first major biological surveys in species were recorded during the surveys, including the the Itombwe Massif in over 30 years revealed that sig- Congo bay owl Phodilus prigoginei, which was previously nificant areas of natural habitat and remnant faunal known from a single specimen collected in Itombwe populations remain, but that these are subject to ongo- nearly 50 years ago. No part of Itombwe is officially ing degradation and over-exploitation. At least 10 areas protected and conservation initiatives are needed ur- of gorilla Gorilla gorilla graueri occurrence, including gently. Given the remoteness and continuing political eight of 17 areas identified during the first survey of the instability of the region, conservation initiatives must species in the massif in 1959, were found. Seventy-nine collaborate with traditional authorities based in the gorilla nest sites were recorded and at least 860 gorillas massif, and should focus at the outset on protecting the were estimated to occupy the massif. Fifty-six species of gorillas and limiting further degradation of key areas. mammals were recorded. Itombwe supports the highest representation, of any area, of bird species endemic to Keywords Afromontane forests, Albertine Rift, Demo- the Albertine Rift highlands. Twenty-two of these cratic Republic of Congo, endemic avifauna, gorillas. -

E-News, Web Sites, and Social Media

70 / Connections: E-news, Web Sites, and Social Media Connections: E-News, Web Sites, and Social Media Africa Biodiversity Collaborative Group Cameroon Primatological Society Website: www.abcg.org Twitter: twitter.com/Camer_primates Facebook: facebook.com/ABCGconserve Twitter: twitter.com/ABCGconserve Canadian-Cameroon Ape Network Facebook: facebook.com/cancamapenetwork/ African Primates (for journal and group) Twitter: twitter.com/CanCamApeNetwrk Website: primate-sg.org/african_primates/ Facebook: facebook.com/groups/AfricanPrimates/ Centre de Conservation pour Chimpanzes Twitter: twitter.com/africanprimates Website: www.projetprimates.com/en/ Facebook: facebook.com/ African Primatological Society CentreDeConservationPourChimpanzes Facebook: facebook.com/African.Primatological. Twitter: twitter.com/projectprimate Society/ Twitter: twitter.com/AfricanPs Chimp Eden (JGI Sanctuary, South Africa) Website: www.chimpeden.com/ African Wildlife Foundation Facebook: facebook.com/JGISA Website: www.awf.org Twitter: twitter.com/jgisachimpeden Facebook: facebook.com/AfricanWildlifeFoundation Twitter: twitter.com/AWF_Official Chimpanzee Sanctuary & Wildlife Conservation Trust (Ngamba Island) Amboseli Baboons Website: www.ngambaisland.org/ Website: www.amboselibaboons.nd.edu E-newsletter contact: [email protected] Facebook: facebook.com/Amboseli-Baboon-Research- Facebook: facebook.com/ngambaisland Project-296131010593283 Twitter: twitter.com/ngambaisland Twitter: twitter.com/AmboseliBaboons Colobus Conservation Barbary Macaque Awareness and Conservation -

The Gertrude Sanford Legendre Papers

The Gertrude Sanford Legendre papers Repository: Special Collections, College of Charleston Libraries Collection number: Mss 0182 Creator: Legendre, Gertrude Sanford, 1902-2000 Title: Gertrude Sanford Legendre papers Date: circa 1800-2013 Extent/Physical description: 171 linear feet (22 cartons, 114 document boxes, 49 slim document boxes, 97 flat storage boxes, 1 roll storage box, 26 negative boxes, 10 oversize folders, 28 audiocassettes, 1 videocassette) Language: English, French, Italian, Arabic, German Abstract: Photograph albums, scrapbooks, photographs, slides, manuscripts, correspondence, ledgers, journals, maps, audiovisual materials, and other papers of Gertrude Sanford Legendre (1902-2000), American socialite, explorer, and author. Materials document Legendre's childhood, education, and travel, including expeditions to Africa and Asia with the American Museum of Natural History and the National Geographic Society, her involvement with the Office of Strategic Services in London and Paris during World War II and her subsequent capture and imprisonment by German forces, and her stewardship, along with her husband, Sidney Legendre, of Medway Plantation (S.C.). Also included are materials related to other members of the Sanford family, their role in politics, and their businesses, including her father, John Sanford (II), and grandfather, Stephen Sanford, who owned Hurricana Farms (later Sanford Stud Farms) and Stephen Sanford & Sons, Inc. Carpet Company (later Bigelow-Sanford); her brother, Stephen "Laddie" Sanford (II), a champion polo player; and her sister, Sarah Jane Cochran Sanford, who married Mario Pansa, an Italian diplomat who served as an advisor to Benito Mussolini before and during World War II. Restrictions on access: This collection is open for research. Copyright notice: The nature of the College of Charleston's archival holdings means that copyright or other information about restrictions may be difficult or even impossible to determine despite reasonable efforts. -

98.6: a Creative Commonality

CONTENT 1 - 2 exibition statement 3 - 18 about the chimpanzees and orangutans 19 resources 20 educational activity 21-22 behind the scenes 23 installation images 24 walkthrough video / flickr page 25-27 works in show 28 thank you EXHIBITION STATEMENT Humans and chimpanzees share 98.6% of the same DNA. Both species have forward-facing eyes, opposing thumbs that accompany grasping fingers, and the ability to walk upright. Far greater than just the physical similarities, both species have large brains capable of exhibiting great intelligence as well as an incredible emotional range. Chimpanzees form tight social bonds, especially between mothers and children, create tools to assist with eating and express joy by hugging and kissing one another. Over 1,000,000 chimpanzees roamed the tropical rain forests of Africa just a century ago. Now listed as endangered, less than 300,000 exist in the wild because of poaching, the illegal pet trade and habitat loss due to human encroachment. Often, chimpanzees are killed, leaving orphans that are traded and sold around the world. Thanks to accredited zoos and sanctuaries across the globe, strong conservation efforts and programs exist to protect and manage populations of many species of the animal kingdom, including the great apes - the chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan and bonobo. In the United States, institutions such as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and the Species Survival Plan (SSP) work together across the nation in a cooperative effort to promote population growth and ensure the utmost care and conditions for all species. Included in the daily programs for many species is what’s commonly known as “enrichment”–– an activity created and employed to stimulate and pose a challenge, such as hiding food and treats throughout an enclosure that requires a search for food, sometimes with a problem-solving component. -

Western Lowland Gorilla (Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla) Diet and Activity Budgets: Effects of Group Size, Age Class and Food Availability in the Dzanga-Ndoki

Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) diet and activity budgets: effects of group size, age class and food availability in the Dzanga-Ndoki National Park, Central African Republic Terence Fuh MSc Primate Conservation Dissertation 2013 Dissertation Course Name: P20107 Title: Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) diet and activity budgets: effects of group size, age class and food availability in the Dzanga-Ndoki National Park, Central African Republic Student Number: 12085718 Surname: Fuh Neba Other Names: Terence Course for which acceptable: MSc Primate Conservation Date of Submission: 13th September 2013 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the regulations for an MSc degree. Oxford Brookes University ii Statement of originality Except for those parts in which it is explicitly stated to the contrary, this project is my own work. It has not been submitted for any degree at this or any other academic or professional institution. ……………………………………………. ………………… Signature Date Regulations Governing the Deposit and Use of Oxford Brookes University Projects/ Dissertations 1. The “top” copies of projects/dissertations submitted in fulfilment of programme requirements shall normally be kept by the School. 2. The author shall sign a declaration agreeing that the project/ dissertation be available for reading and photocopying at the discretion of the Head of School in accordance with 3 and 4 below. 3. The Head of School shall safeguard the interests of the author by requiring persons who consult the project/dissertation to sign a declaration acknowledging the author’s copyright. 4. Permission for any one other then the author to reproduce or photocopy any part of the dissertation must be obtained from the Head of School who will give his/her permission for such reproduction on to an extent which he/she considers to be fair and reasonable. -

Who Knows What About Gorillas? Indigenous Knowledge, Global Justice, and Human-Gorilla Relations Volume: 5 Adam Pérou Hermans Amir, Ph.D

IK: Other Ways of Knowing Peer Reviewed Who Knows What About Gorillas? Indigenous Knowledge, Global Justice, and Human-Gorilla Relations Volume: 5 Adam Pérou Hermans Amir, Ph.D. Pg. 1-40 Communications Coordinator, Tahltan Central Government The gorillas of Africa are known around the world, but African stories of gorillas are not. Indigenous knowledge of gorillas is almost entirely absent from the global canon. The absence of African accounts reflects a history of colonial exclusion, inadequate opportunity, and epistemic injustice. Discounting indigenous knowledge limits understanding of gorillas and creates challenges for justifying gorilla conservation. To be just, conservation efforts must be endorsed by those most affected: the indigenous communities neighboring gorilla habitats. As indigenous ways of knowing are underrepresented in the very knowledge from which conservationists rationalize their efforts, adequate justification will require seeking out and amplifying African knowledge of gorillas. In engaging indigenous knowledge, outsiders must reflect on their own ways of knowing and be open to a dramatically different understanding. In the context of gorillas, this means learning other ways to know the apes and indigenous knowledge in order to inform and guide modern relationships between humans and gorillas. Keywords: Conservation, Epistemic Justice, Ethnoprimatology, Gorilla, Local Knowledge, Taboos 1.0 Introduction In the Lebialem Highlands of Southwestern Cameroon, folk stories tell of totems shared between gorillas and certain people. Totems are spiritual counterparts. Herbalists use totems to gather medicinal plants; hunting gorillas puts them in doi 10.26209/ik560158 danger. If the gorilla dies, the connected person dies as well (Etiendem 2008). In Lebialem, killing a gorilla risks killing a friend, elder, or even a chief (fon). -

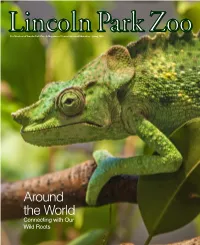

Around the World

For Members of Lincoln Park Zoo · A Magazine of Conservation and Education · Spring 2016 Around the World Connecting with Our Wild Roots DEPARTMENTS IN THIS ISSUE Perspective Volume 15, Number 1 · For Members of Lincoln Park Zoo 1 President and CEO Kevin Bell highlights how zoos around the globe connect visitors with wildlife—and are increasingly working together to save it. 16 Plant Provenance Native and exotic species share space in the zoo’s gardens, where horticulturists aim for interest in all four seasons. 18 News of the Zoo Chimpanzee close-ups, updates on new zoo buildings and a look back at the brilliance of ZooLights Present- ed By ComEd and PowerShares QQQ. 19 Wild File Baby monkeys stand out, snowy species head out- FEATURES doors and the zoo animal hospital makes a move. 2 Wild City 20 Membership Matters You might think the “Chicago ecosystem” offers few Save the date for Members-Only Morning, SuperZoo- surprises, but zoo scientists are spotting plenty of Picnic and a summer series of member tours. unexpected wildlife in this urban range. 21 Calendar 4 Climbing the Canopy Step into spring with fun zoo events, including our Monkeys skitter, jaguars prowl and sloths…stay put new Food Truck Social! as we take a trip up into the canopy of the South American rainforest. Continue Your Visit Online Visit lpzoo.org for Lincoln Park Zoo photos, videos Where Rainforest Still Rules and up-to-date info on events and animals. You can 6 also find us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram! The wilds of the Goualougo Triangle are one of the most pristine places on Earth, a zoo study site and an We'd Like to Hear from You! Send your feedback on this issue of untouched home for gorillas and chimpanzees. -

Great Ape Conservation Fund Grants, 2003

DIVISION OF INTERNATIONAL CONSERVATION GREAT APES CONSERVATION FUND SUMMARY OF GRANTS 2004 The Yellow-cheeked Crested Gibbons (Nomascus gabriellae) of Cat Tien National Park: Assessing Their Status, and Increasing Their Conservation Profile in the Local Community, Vietnam. In partnership with Cat Tien National Park. FWS: $21,500. Leveraged funds: $8,061. To include developing recommendations for the management of gibbons and their habitat; and activities to raise local peoples awareness of the need to reduce human impact on the gibbons and their habitat. A National Survey of Pileated Gibbons (Hylobates pileatus) to Identify Their Current status, Viable Populations and Recommendations for Their Long-term Conservation, Thailand. In partnership with WWF-Thailand. FWS: $27,075. Leveraged funds: $12,605. This will allow comparison of current data on the species status in the country with that of an earlier study to determine the population’s trend. Orangutan Conservation and Habitat Protection in Gunung Palung National Park, Indonesia. In partnership with The President and Fellows of Harvard College. FWS: $50,000. Leveraged funds: $109,250. To raise public awareness on forest and orangutan conservation in the park through school presentations and field trips, initiate development of an environmental education center, train local guides and interpreters, implement an awareness campaign on illegal logging, produce a film on the park for presentation to local people, and develop and implement a habitat protection plan. Orangutan Protection and Monitoring Unit, Indonesia. In partnership with Fauna and Flora International. FWS: $49,970. Leveraged funds: $5,560. Continue support of three-four person Orangutan Protection and Monitoring Units to protect orangutan and their habitat at Gunung Palung National Park and its surrounding buffer zone.