U.S. Children 10 Years After Hurricane Katrina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Governor's Commission to Rebuild Texas

EYE OF THE STORM Report of the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas John Sharp, Commissioner BOARD OF REGENTS Charles W. Schwartz, Chairman Elaine Mendoza, Vice Chairman Phil Adams Robert Albritton Anthony G. Buzbee Morris E. Foster Tim Leach William “Bill” Mahomes Cliff Thomas Ervin Bryant, Student Regent John Sharp, Chancellor NOVEMBER 2018 FOREWORD On September 1 of last year, as Hurricane Harvey began to break up, I traveled from College Station to Austin at the request of Governor Greg Abbott. The Governor asked me to become Commissioner of something he called the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas. The Governor was direct about what he wanted from me and the new commission: “I want you to advocate for our communities, and make sure things get done without delay,” he said. I agreed to undertake this important assignment and set to work immediately. On September 7, the Governor issued a proclamation formally creating the commission, and soon after, the Governor and I began traveling throughout the affected areas seeing for ourselves the incredible destruction the storm inflicted Before the difficulties our communities faced on a swath of Texas larger than New Jersey. because of Harvey fade from memory, it is critical that Since then, my staff and I have worked alongside we examine what happened and how our preparation other state agencies, federal agencies and local for and response to future disasters can be improved. communities across the counties affected by Hurricane In this report, we try to create as clear a picture of Harvey to carry out the difficult process of recovery and Hurricane Harvey as possible. -

A FAILURE of INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina

A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina U.S. House of Representatives 4 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Union Calendar No. 00 109th Congress Report 2nd Session 000-000 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Report by the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoacess.gov/congress/index.html February 15, 2006. — Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U. S. GOVERNMEN T PRINTING OFFICE Keeping America Informed I www.gpo.gov WASHINGTON 2 0 0 6 23950 PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 COVER PHOTO: FEMA, BACKGROUND PHOTO: NASA SELECT BIPARTISAN COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE PREPARATION FOR AND RESPONSE TO HURRICANE KATRINA TOM DAVIS, (VA) Chairman HAROLD ROGERS (KY) CHRISTOPHER SHAYS (CT) HENRY BONILLA (TX) STEVE BUYER (IN) SUE MYRICK (NC) MAC THORNBERRY (TX) KAY GRANGER (TX) CHARLES W. “CHIP” PICKERING (MS) BILL SHUSTER (PA) JEFF MILLER (FL) Members who participated at the invitation of the Select Committee CHARLIE MELANCON (LA) GENE TAYLOR (MS) WILLIAM J. -

Final Report on Formaldehyde Levels in FEMA-Supplied Travel Trailers, Park Models, and Mobile Homes

Final Report on Formaldehyde Levels in FEMA-Supplied Travel Trailers, Park Models, and Mobile Homes From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention July 2, 2008 Amended December 15th, 2010 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... iii Background ......................................................................................................................................1 CDC Testing of Occupied Trailers ..............................................................................................1 Formaldehyde Exposure in Residential Indoor Air .....................................................................3 Health Effects...............................................................................................................................4 Regulations and Standards of Formaldehyde Levels ...................................................................5 Objectives ........................................................................................................................................5 Methods............................................................................................................................................5 Study Personnel………………………………………………………………………................6 Trailer Selection ...........................................................................................................................6 Eligibility Criteria ........................................................................................................................7 -

Music 6581 Songs, 16.4 Days, 30.64 GB

Music 6581 songs, 16.4 days, 30.64 GB Name Time Album Artist Rockin' Into the Night 4:00 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Caught Up In You 4:37 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Hold on Loosely 4:40 Wild-Eyed Southern Boys .38 Special Voices Carry 4:21 I Love Rock & Roll (Hits Of The 80's Vol. 4) 'Til Tuesday Gossip Folks (Fatboy Slimt Radio Mix) 3:32 T686 (03-28-2003) (Elliott, Missy) Pimp 4:13 Urban 15 (Fifty Cent) Life Goes On 4:32 (w/out) 2 PAC Bye Bye Bye 3:20 No Strings Attached *NSYNC You Tell Me Your Dreams 1:54 Golden American Waltzes The 1,000 Strings Do For Love 4:41 2 PAC Changes 4:31 2 PAC How Do You Want It 4:00 2 PAC Still Ballin 2:51 Urban 14 2 Pac California Love (Long Version 6:29 2 Pac California Love 4:03 Pop, Rock & Rap 1 2 Pac & Dr Dre Pac's Life *PO Clean Edit* 3:38 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2006 2Pac F. T.I. & Ashanti When I'm Gone 4:20 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3:58 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Bailen (Reggaeton) 3:41 Tropical Latin September 2002 3-2 Get Funky No More 3:48 Top 40 v. 24 3LW Feelin' You 3:35 Promo Only Rhythm Radio July 2006 3LW f./Jermaine Dupri El Baile Melao (Fast Cumbia) 3:23 Promo Only - Tropical Latin - December … 4 En 1 Until You Loved Me (Valentin Remix) 3:56 Promo Only: Rhythm Radio - 2005/06 4 Strings Until You Love Me 3:08 Rhythm Radio 2005-01 4 Strings Ain't Too Proud to Beg 2:36 M2 4 Tops Disco Inferno (Clean Version) 3:38 Disco Inferno - Single 50 Cent Window Shopper (PO Clean Edit) 3:11 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2005 50 Cent Window Shopper -

Evans-Cowley: Post-Katrina Housing 95 International Journal of Mass

Evans-Cowley: Post-Katrina Housing International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters August 2011, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 95–131. Planning for a Temporary-to-Permanent Housing Solution in Post-Katrina Mississippi: The Story of the Mississippi Cottage Jennifer Evans-Cowley Joseph Kitchen Department of City and Regional Planning Ohio State University Email: [email protected] Abstract Immediately following Hurricane Katrina, the Mississippi Governor’s Commission for Recovery, Rebuilding, and Renewal collaborated with the Congress for the New Urbanism to generate rebuilding proposals for the Mississippi Gulf Coast. One of the ideas generated from this partnership was the Katrina Cottage—a small home that could serve as an alternative to the FEMA Trailer. The State of Mississippi participated in the Pilot Alternative Temporary Housing (PATH) program, which was funded by the U.S. Congress. This study examines how local governments and residents responded to the Mississippi Cottage Program. This study finds that while the Mississippi Cottage program did provide citizens with needed housing following Hurricane Katrina, there are significant policy and implementation challenges that should be addressed before future disasters. The paper concludes by offering recommendations on how communities across can prepare to provide temporary housing in their communities. Keywords: disaster housing, Hurricane Katrina, FEMA, Mississippi Cottage, post- disaster planning Introduction Hurricane Katrina brought Category Three winds and Category Five storm surge to the Gulf Coast. After the hurricane, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) deployed trailers and manufactured homes, the typical forms of temporary housing deployed by the agency after disasters (Garratt 2008). After Hurricane Katrina, 95 Evans-Cowley: Post-Katrina Housing FEMA had to deploy 140,000 different temporary housing units in the form of travel trailers, mobile homes, and manufactured housing (Garratt 2008). -

Instrumental Song Gospel Song Mariachi Song Vocal Duo Bilingual Song Mark Ipiotis Award

NMHMA Hispano Music Awards Nominees-2016 . SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Instrumental El Zopilote Mojado Mario Romero Gunshot Los Serranos Y Familia Song Polka Melodia Grupo Melodia of The Year Polka Zapatos Gony, Barbara & The Boyz Valse De Mis Padres The Dave Maestas Band SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Gospel Desde Que Dios Amanece Marcelina Velasquez Mundo Malo Cuarenta Y Cinco Song No Hay Dios Como Tu Jerry Dean & Alex Garcia of the Year Pescador De Hombres Al Hurricane Jr. Te Vas Angel Mio Bobby Madrid & Christina Perea SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Mariachi Cielito Lindo Huasteco Mariachi Sonidos Del Monte Song El Jinete Antonio Reyna of The Year El Mundo Es Mio Eddie Y Vengancia Te Vas Angel Mio Christina Perea Y Bobby Madrid VOCAL DUO SONG TITLE Vocal Christina Perea & Anita Lopez Flor De Las Flores Darren Cordova & Matthew Martinez Dos Hombres Y Un Destino Duo Jerry Dean & Christian Sanchez Mi Padrecito of The Year Severo Martinez & Jenna Baila Conmigo Tanya Griego & Justin Anaya Regresa Muy Pronto A Mi SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Bilingual Before The Next Tear Drop Falls Andrew Gonzales En El Mistico Black Pearl Band NM Song I Need to Know-Aye Dimelo Latino Persuasion of The Year Please Don’t Go Chelsea Chavez Wasted Days & Wasted Nights Miguel Timoteo NOMINEE Mark Glenda Martinez/KDCE Radio Ipiotis Kevin Otero-KANW Radio Mariachi Mike/KDCE Radio Award Mike Baca/KFUN Radio Norberto Martinez/KXMT Radio NMHMA Hispano Music Awards Nominees-2016 . SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Conjunto Chiquito Pero Picoso Rhythm Divine Norteño La Mala Vida Latino Persuasion Song Ojitos Verdes Eddie Y Venganzia of The Year Que Te Faltaba Andrew Gonzales Soy Toda Tuya Tanya Griego SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Crossover Chile Verde Rock Lluvia Negra Band El Retrato Chris Arellano Song En El Mistico Black Pearl Band NM of The Year I Got Mexico Cuarenta Y Cinco Please Don’t Go Chelsea Chavez SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Cumbia Doña Juana Dwayne Ortega Band El Regañado Cuarenta Y Cinco Song La Roncona Al Hurricane Jr. -

Albuquerque Museum Oral History Project Johnny J. Armijo November 26, 2002 This Interview Was Conducted As Part of a Project By

Albuquerque Museum Oral History Project Johnny J. Armijo November 26, 2002 This interview was conducted as part of a project by the Albuquerque Museum to document the lives of people living in various city neighborhoods. Keywords and topics: Thee Chekkers, the South Valley, the Bosque, growing up in the South Valley, Ernie Pyle Middle School, Jack Ayala, Jerry Pacheco, Alfred Romero, David Nuñez, Nick Luchetti, Randy Castillo, Horn Oil, Atrisco Land Grant, Conrad Hilton, alcoholism, DWI Planning Council, Don Lesman’s Music Box, living in Salt Lake City, gang activity in the South Valley, Chicanismo, Sidro Garcia, Tom Barsanti, The Czars, Jim Burgett, Sloopy and the Red Barons, Fuller Brush and Rainbow Vacuum, Al Hurricane, Bennie Sanchez, meeting James Brown, Transmission Magazine, Los Padillas Community Center programming STEVENSON: This is Glen Stevenson with Johnny J. Armijo, November 25? ARMIJO: Sixth STEVENSON: Sixth. At the Los Padillas Community Center, in the South Valley. ARMIJO: Two thousand two. STEVENSON: Thanks, Johnny. ARMIJO: That was okay? [Interview starts at 00:22] ARMIJO: Part of what we were talking about is—or that I was talking about—is that, uh, I’m going to take you back, back, back. My dad was in a band—several bands, actually—he played with the Don Lesman Band, and he was in the 44th Army Band with the National Guard, J.J. Armijo, Johnny Jeremy. Anyway, from him and his band—he was a sax [saxophone] player: alto, tenor, and what’s the other one? Clarinet. [papers being shuffled in background] Played a little bit of piano. -

FEMA Response to Formaldehyde in Trailer, OIG-09-83

Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General FEMA Response to Formaldehyde in Trailers (Redacted) Notice: The Department of Homeland Security, Office of the Inspector General, has redacted this report for public release. OIG-09-83 June 2009 Office of Inspector General U.S. Department of Homeland Security Washington, DC 25028 June 26, 2009 Preface The Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General was established by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (Public Law 107-296) by amendment to the Inspector General Act of 1978. This is one of a series of audit, inspection, and special reports prepared as part of our oversight responsibilities to promote economy, efficiency, and effectiveness within the department. This report addresses the strengths and weaknesses of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s decision making, policy, and procedures related to the issue of formaldehyde in trailers purchased by the agency to house victims of the 2005 Gulf Coast hurricanes. It is based on interviews with employees and officials of relevant agencies and institutions, direct observations, and a review of applicable documents. The recommendations herein have been developed to the best knowledge available to our office, and have been discussed in draft with those responsible for implementation. We trust that this report will result in more effective, efficient, and economical operations. We express our appreciation to all of those who contributed to the preparation of this report. Richard L. Skinner Inspector General Table of -

Casualties of Katrina.Pdf

A CORPWATCH REPORT BY ELIZA STRICKLAND AND AZIBUIKE AKABA CASUALTIES OF KATRINA GULF COAST RECONSTRUCTION TWO YEARS AFTER THE HURRICANE AUGUST 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . .1 PART ONE: RETURNING HOME . .2 Back on the Bayou: Electricity & Energy . .2 Insurance: State Farm . .4 “Road Home” Program . .6 Trailer Parks and Tarps: The Shaw Group and Fluor . .8 PART TWO: REPAIRING THE REGION . .10 Levees: Moving Water . .10 Debris: Surrounded by Dumps . .13 Refineries: Cleaning Up Big with Hurricane Aid . .15 Mulching the Cypress Swamps . .17 PART THREE: REVIVAL? . .18 Casinos: Gambling Bonanza . .18 Labor: Exploiting Migrants, Ignoring Locals . .19 Small Business Contracts . .21 Reconsidering the Rush to Rebuild the Big Easy . .23 ENDNOTES . .26 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . .29 Cover images: Chef Menteur protest. Photo by Darryl Malek-Wiley, Sierra Club Sacred Heart Academy High School students demonstrate for levee repairs, January 2006. Photo by Greg Henshall, FEMA Housing Authority of New Orleans protest, August 2007. Photo: New Orleans Indymedia Aerial of flooded neighborhood in New Orleans. Photo by Jocelyn Augustino, FEMA This page: Flood water pumps in Marin, Louisiana. Photo by Marvin Nauman, FEMA HOUSTON, WE HAVE A PROBLEM New Orleans, September 4, 2005. Photo by Jocelyn Augustino, FEMA INTRODUCTION This CorpWatch report by Eliza Strickland and Azibuike Akaba tells the story of corporate malfeasance and government incompetence two years after Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans. This is our second report—Big, Easy Money by Rita J. King was the first—and it digs into a slew of new scandals. We have broken the report up into three parts: the struggle at the electricity and timber companies who have taken by ordinary residents to return home, the major effort to fix advantage of the emergency aid to expand, rather than limit, the broken Gulf Coast infrastructure, and finally—what the the impact of their environmentally destructive businesses. -

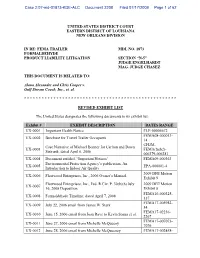

Fema Trailer Mdl No. 1873 Formaldehyde Product Liability Litigation Section “N-5” Judge Engelhardt Mag

Case 2:07-md-01873-KDE-ALC Document 2208 Filed 07/17/2009 Page 1 of 62 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA NEW ORLEANS DIVISION IN RE: FEMA TRAILER MDL NO. 1873 FORMALDEHYDE PRODUCT LIABILITY LITIGATION SECTION “N-5” JUDGE ENGELHARDT MAG. JUDGE CHASEZ THIS DOCUMENT IS RELATED TO: Alana Alexander and Chris Cooper v. Gulf Stream Coach, Inc., et. al. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * REVISED EXHIBIT LIST The United States designates the following documents to its exhibit list: Exhibit # EXHIBIT DESCRIPTION BATES RANGE UX-0001 Important Health Notice FLE-00005672 FEMA08-000013- UX-0002 Brochure for Travel Trailer Occupants 14 CH2M- Case Narrative of Michael Bonner for Carlton and Dawn UX-0003 FEMA(Sub2)- Sistrunk, dated April 6, 2006 006379-006381 UX-0004 Document entitled, “Important Notices” FEMA09-000363 Environmental Protection Agency’s publication, An UX-0005 EPA-000001-4 Introduction to Indoor Air Quality 2009 DFE Motion UX-0006 Fleetwood Enterprises, Inc., 2006 Owner’s Manual. Exhibit 9 Fleetwood Enterprises, Inc., Fed. R.Civ. P. 30(b)(6) July 2009 DFE Motion UX-0007 16, 2008 Deposition. Exhibit 8 FEMA10-000325- UX-0008 Formaldehyde Timeline, dated April 7, 2008 337 FEMA17-005982- UX-0009 July 22, 2006 email from James W. Stark 84 FEMA17-02236- UX-0010 June 15, 2006 email from Joan Rave to Kevin Souza et al. 2267 FEMA17-007073- UX-0011 June 27, 2006 email from Michelle McQueeny 7076 UX-0012 June 28, 2006 email from Michelle McQueeney FEMA17-002458- Case 2:07-md-01873-KDE-ALC Document 2208 Filed 07/17/2009 Page 2 of 62 2459 UX-0013 March 17, 2006 email from Dan Shea to Stephen Miller FEMA17-022333 (FEMA-Waxman- UX-0014 March 17, 2006 email from David Porter to Mary Martinet 3623 May 31, 2006 Formaldehyde Statistics Memo for Jesse FEMA10-000163- UX-0015 Crowley from Bronson Brown 164 U.S. -

HM 108 Page 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

1 A MEMORIAL 2 RECOGNIZING THE HISPANIC HERITAGE COMMITTEE FOR ITS 3 COLLABORATION EFFORTS IN PROMOTING GREATER AWARENESS, 4 APPRECIATION AND CULTURAL PRESERVATION OF NEW MEXICO MUSIC 5 AND MARIACHI MUSIC IN NEW MEXICO FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS. 6 7 WHEREAS, New Mexico music stretches back centuries, with 8 roots in thirteenth century pueblo music, and incorporates 9 ranchera, Navajo, country and western folk styles; and 10 WHEREAS, New Mexico music is a unique musical genre, 11 recognized for its up-tempo rhythms, ranchera polka, bolero 12 rhythms and distinctive vocals; and 13 WHEREAS, New Mexico music has been influenced by many 14 legendary New Mexican artists, such as Al Hurricane, Al 15 Hurricane, Jr., Tobias Rene, the Blue Ventures band, Gonzalo, 16 Sparx, Lorenzo Antonio and Darren Cordova; and 17 WHEREAS, mariachi music has New Mexico's historical 18 influence and instills pride in cultural heritage; and 19 WHEREAS, mariachi music is historically known as "la 20 musica de la gente", or music of the people, the common folk, 21 with musical ballads that describe an array of human 22 emotions, including feelings of nostalgia that bring 23 communities together to celebrate life while connecting to 24 the rich traditions of the past; and 25 WHEREAS, the Hispanic heritage committee has identified HM 108 Page 1 1 the decline in popularity of both New Mexico music and 2 mariachi music in New Mexico; 3 NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE HOUSE OF 4 REPRESENTATIVES OF THE STATE OF NEW MEXICO that the Hispanic 5 heritage committee be recognized -

Hurricane Effects on Neotropical Lizards Span Geographic and Phylogenetic Scales

Hurricane effects on Neotropical lizards span geographic and phylogenetic scales Colin M. Donihuea,1, Alex M. Kowaleskib, Jonathan B. Lososa,c,1, Adam C. Algard, Simon Baeckense,f, Robert W. Buchkowskig, Anne-Claire Fabreh, Hannah K. Franki,j, Anthony J. Genevak,l, R. Graham Reynoldsm, James T. Strouda, Julián A. Velascon, Jason J. Kolbeo, D. Luke Mahlerp, and Anthony Herrele,q,r aDepartment of Biology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO 63130; bDepartment of Meteorology and Atmospheric Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; cLiving Earth Collaborative, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO 63130; dSchool of Geography, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD Nottingham, United Kingdom; eFunctional Morphology Lab, Department of Biology, University of Antwerp, B-2610 Wilrijk, Belgium; fDepartment of Biological Science, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia; gSchool of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511; hDepartment of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom; iDepartment of Pathology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305; jDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70118; kDepartment of Vertebrate Biology, The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA 19103; lDepartment of Biodiversity, Earth, and Environmental Science, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA 19104; mDepartment of Biology, University of North Carolina Asheville, Asheville, NC 28804; nCentro de Ciencias de la Atmósfera, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 04510 Mexico City, Mexico; oDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI 02881; pDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 3B2, Canada; qUMR7179, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique/Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 75005 Paris, France; and rEvolutionary Morphology of Vertebrates, Ghent University, 9000 Ghent, Belgium Contributed by Jonathan B.