International Migration of the Jews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Were Jews Political Refugees Or Economic Migrants?

The New Comparative Economic History Essays in Honor of Jeffrey G. Williamson Edited by Timothy J. Hatton, I(evin H. O'Rourke, and Alan M. Taylor The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Were Jews Political Refugees or Economic Migrants? 11 Assessing the Persecution Theory of Jewish Emigration, 1881-1914 Leah Platt Boustan [11 1881, 4.1 Illillion Jews lived in the Russian empire. Over the next three decades, 1.5 million Russian Jews immigrated to the United States, and another 0.5 million left for other New World destinations, a mass migra tion surpassed in strength only by the Irish earlier in the century. Despite the intensity of Jewish migration, economic historians have paid lillle at tenlion to this episode. 1 This is clue, in pare to a lack of comparable data between Russia and the rest of continental Europe, but it also reilects the common belief that the exodus from Russia was a uniquely Jewish event and thus cannot be incorporated into a general model of migration as fac tor Bows. In this chapter, I argue that a confluence of demographic events, including population growth and internal migration from villages to larger cities, set the flow of Jewish migrants from Russia in motion. I fur ther demonstrate that the timing of Jewish migration, once it had begun in earnest, was influenced both by periodic religious violence and by busi ness cycles in the United States and Russia. Migration rates increased temporarily in the year after 11 documented persecution. In addition, by enlarging the slock of Jews living in the United States, many of whom joined emigrant aid societies or paid directly for their family's passage, temporary religious violence had modest long-run effects on the magni tude of the Jewish migration flow. -

GONE to TEXAS: PART of the NATION's IMMIGRATION STORY from the Bullock Texas State History Museum

GONE TO TEXAS: PART OF THE NATION'S IMMIGRATION STORY from the Bullock Texas State History Museum Children and Youth Bibliography (*denotes Galveston/Texas-focus) Elementary School Connor, Leslie illustrated by Mary Azarian. Miss Bridie Chose a Shovel. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. Miss Bridie embarks on a voyage to America in 1856. She chooses to bring along a shovel to start a new life in a new land. In this children's book, a young Irish woman's journey symbolizes the contribution made by millions of immigrants in building our nation. Freeman, Marilyn. Pasquale's Journey. New York University Press, 2003. Join Pasquale and his family on a journey from Italy to America. After receiving tickets from “Papa,” they start their long, exhausting voyage, all the time dreaming of a better life! Glasscock, Sarah. Read Aloud Plays: Immigration. Scholastic, 1999. This collection of plays will give students an opportunity to actively learn about Irish, Chinese, Lebanese, Cuban, and Russian Jews immigrating for a number of reasons. Herrera, Juan Felipe illustrated by Honorio Robledo Tapia. Super Cilantro Girl. Children's Book Press, 2003. This is a tale about a super-hero child who flies huge distances and scales tall walls in order to rescue her mom. Juan Felipe Herrera addresses and transforms the concerns many first-generation children have about national borders and immigrant status. Lawrence, Jacob. The Great Migration: An American Story. HarperCollins, 1995. This book chronicles the migration of African Americans from the South to replace workers because of WWI. It touches upon discrimination and sharecropping as well as the new opportunities of voting and going to school. -

Rabbi Henry Cohen and the Galveston Immigration Movement, 1907-1914

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 15 Issue 1 Article 8 3-1977 Rabbi Henry Cohen and the Galveston immigration Movement, 1907-1914 Ronald A. Axelrod Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Axelrod, Ronald A. (1977) "Rabbi Henry Cohen and the Galveston immigration Movement, 1907-1914," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 15 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol15/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 24 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION RABBI HENRY COHEN AND THE GALVESTON IMMIGRATION MOVEMENT* 1907-1914 By Ronald A. Axelrod The role men and women play in history can be viewed from two perspec tives. Either men determine history by their actions or history determines the actions of men. At times a combination of the two may take place. The relationship of Rabbi Henry Cohen 0863-1952) of Galveston and the Galves ton Immigration Movement, often called the Galveston Plan, was a case of combining these two historical perspectives. The necessity of a nation and a religious group to change its immigration patterns coupled with the extra ordinary humanitarian efforts of a great man created the product of an innova tive, well-planned program. This paper will examine the workings of the Galveston Plan and the role Henry Cohen played in making that plan a partial success. -

Teaching Immigration with the Immigrant Stories Project LESSON PLANS

Teaching Immigration with the Immigrant Stories Project LESSON PLANS 1 Acknowledgments The Immigration History Research Center and The Advocates for Human Rights would like to thank the many people who contributed to these lesson plans. Lead Editor: Madeline Lohman Contributors: Elizabeth Venditto, Erika Lee, and Saengmany Ratsabout Design: Emily Farell and Brittany Lynk Volunteers and Interns: Biftu Bussa, Halimat Alawode, Hannah Mangen, Josefina Abdullah, Kristi Herman Hill, and Meredith Rambo. Archival Assistance and Photo Permissions: Daniel Necas A special thank you to the Immigration History Research Center Archives for permitting the reproduction of several archival photos. The lessons would not have been possible without the generous support of a Joan Aldous Diversity Grant from the University of Minnesota’s College of Liberal Arts. Immigrant Stories is a project of the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota. This work has been made possible through generous funding from the Digital Public Library of America Digital Hubs Pilot Project, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. About the Immigration History Research Center Founded in 1965, the University of Minnesota's Immigration History Research Center (IHRC) aims to transform how we understand immigration in the past and present. Along with its partner, the IHRC Archives, it is North America's oldest and largest interdisciplinary research center and archives devoted to preserving and understanding immigrant and refugee life. The IHRC promotes interdisciplinary research on migration, race, and ethnicity in the United States and the world. It connects U.S. immigration history research to contemporary immigrant and refugee communities through its Immigrant Stories project. -

Interview with John Arcudi, by Debbie Elkin, for the Bridgeport Public

Historical Collections, Bridgeport Public Library Oral History Project: “Bridgeport Working: Voices from the 20th Century” John Arcudi (JA) interviewed by Dr. Debbie Elkin (I), December 16, 1997 Transcript Part 1: Early life in Saugatuck-Westport, Connecticut; Italian American family; the Depression Part 2: Yale University in the 1930’s and 1940’s; Family Part 3: WWII Service with SHAEF and General Patton Part 4: Decision to go to law school; Family influences Part 5: Decision to open law practice in Bridgeport; Early work with unions; American Veterans Committee (AVC) Part 6: Political influences at Yale and from home experience; Unemployment Compensation Commission Part 7a: Unemployment Compensation Commission Part 7: Labor law practice in Bridgeport; Work with AFL, Mine, Mill and Smelters, Union, IUE, and ILGW Part 8: Immigration law practice Part 9: International Institute Part 10: Council of Italian Americans Society, Triancria Society, Italian Community Center, Columbus Day Parade, Italian dialects and regionalism Historical Collections, Bridgeport Public Library Oral History Project: “Bridgeport Working: Voices from the 20th Century” John Arcudi (JA) interviewed by Dr. Debbie Elkin (I), December 16, 1997 I: Would you mind saying your name for the tape? JA: John Arcudi. I: Thank you. Would you mind telling me something about your childhood? JA: Well, I was born in Westport, Connecticut and educated in the Westport Public Schools. My parents -- we lived above a grocery and meat market that my parents ran. Born May 26, 1921, whatever that means. I graduated from Staples High School in 1938. I went to Yale and graduated Yale, with a major in Economics, in 1942, did a term of law school, went off to war, served in the U.S. -

Immigration and Immigrants

IMMIGRATION AND IMMIGRANTS SETTING THE RECORD STRAIGHT MICHAEL FIX AND JEFFREY S. PASSEL with María E. Enchautegui and Wendy Zimmermann May 1994 THE URBAN INSTITUTE • WASHINGTON, D.C. i THE URBAN INSTITUTE is a nonprofit, nonpartisan policy research organization established in Washington, D.C., in 1968. Its staff investigates the social and economic problems confronting the nation and assesses public and private means to alleviate them. The Institute seeks to sharpen thinking about society’s problems and efforts to solve them, improve government decisions and performance, and increase citizen awareness about important public choices. Through work that ranges from broad conceptual studies to administrative and technical assistance, Institute researchers contribute to the stock of knowledge available to guide decisionmaking in the public interest. In recent years this mission has expanded to include the analysis of social and economic problems and policies in developing coun- tries and in the emerging democracies of Eastern Europe. Immigrant Policy Program The Urban Institute’s Immigrant Policy Program was created in 1992 with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The overall goal of the program is to research, design, and promote policies that integrate newcomers into the United States. To that end, the program seeks to: 1) Develop systematic knowledge on immigrants’ economic mobility and social integration, and the public policies that influence them; 2) Disseminate knowledge broadly to government agencies, non- profit organizations, scholars, and the media; and 3) Advise policymakers on the merits of current and proposed policies. Program for Research on Immigration Policy The Program for Research on Immigration Policy was established in 1988 with ini- tial core support from The Ford Foundation. -

The Galveston Movement

131 Early Twentieth Century Networks of Ethnicity: The Galveston Movement Susan W. Hardwick I have often thought that if it had not been for Jacob Schiff, I might well be living in a tenement in the Lower East Side of New York without ever having had the opportunity to become a Texan. —Leo J. Hoffman, 2001 napshot images of refugees arriving in the U.S. from Eastern Eu- rope and Russia usually depict scenes of exhausted newcomers Shuddled on shipboard just off Ellis Island, or crowded tenements in New York’s Lower East Side. Nowhere in these images are pictures of Russian immigrants wearing wool coats and fur hats stepping off German passenger ships onto the Texas Gulf Coast. Historical geographers and other scholars have long been interested in the migration, settlement, and impacts of new immigrants in the U.S. Yet, despite an extensive list of prior studies of Jewish refugees forced to flee their homelands to relocate to the U.S., little to date has been said about a surprising and relatively undocumented migration stream between isolated villages in Eastern Europe with the port city of Galveston, Texas.1 This dramatic episode in international migration history, known as the Galveston Movement, lasted from 1907 through 1914. Ultimately, a broad political, cultural, social, and economic network linked more than 10,000 Russian Jewish migrants to the South and the interior U.S. by way of Galveston, the “Ellis Island of Texas.” In this article, “networks of ethnicity” connecting North America and Eastern Europe are analyzed through the lens of two seemingly disparate sets of images—Jewish refugees fleeing persecution from devastated rural villages in Russia and Ukraine, and a hot, humid Gulf Coast port. -

Abstract Views of Aging Among Immigrant Russian

ABSTRACT VIEWS OF AGING AMONG IMMIGRANT RUSSIAN-SPEAKING OLDER WOMEN by Polina Ermoshkina More than a million immigrants from the former Soviet Union are currently living in the United States. Many of those immigrants arrived to the United States in older age. While previous studies were focused on the Russian immigrants’ utilization of healthcare services in the United States, almost no studies examined the older Russian-speaking immigrants’ hardships in the Soviet Union. A thematic analysis approach was used to analyze interviews conducted with 16 immigrant women from a Mid-Atlantic region, who moved to the US after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Seven identified themes were broken down by two major categories: childhood and adulthood in the Soviet Union and older age in the United States. The findings suggest that views of long-term care, intergenerational support, and socio-economic status are deeply rooted in the cultural and societal expectations of the country of origin. VIEWS OF AGING AMONG IMMIGRANT RUSSIAN-SPEAKING OLDER WOMEN A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Gerontological Studies Department of Sociology and Gerontology by Polina V. Ermoshkina Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2014 Advisor________________________ (Dr. Kate de Medeiros) Reader_________________________ (Dr. Jennifer Kinney) Reader_________________________ (Dr. Jennifer Bulanda) Table of Contents Background 1-7 Methods 7-9 Results 10-26 Conclusion/Discussion 26-29 References 30-33 Appendix: The Interview Guide 34-36 ii Acknowledgments Data reported in this paper derived from two research projects, “Lifestyles and Generativity of Childless Older Women” (AG030614; PI: Robert Rubinstein) and “Lifestyles and Generativity of Older Russian Women” (AG030614-S1; PI: Robert Rubinstein). -

Galvestonians View Immigration, 1875-1914

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 38 Issue 1 Article 7 3-2000 Galvestonians View Immigration, 1875-1914 Barbara J. Rozek Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Rozek, Barbara J. (2000) "Galvestonians View Immigration, 1875-1914," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 38 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol38/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 15 "GALVESTONIANS VIEW IMMIGRATION, 1875-1914" hy Barbara J. Rozek Galveston has seen itself first and foremost as a port city. Its geographic position dictated this view of life and provided the driving force that made Galveston the premier city in Texas during much of the nineteenth century. As a port city, commerce and transportation remained the focus of business and influenced most of the daily activity of the city. While primarily concerned with the current of goods flowing into and out of the port, the tide of people became a major interest as well. For Galvestonians, whatever encouraged or helped the commercial flow of "things" was good for the city. Thus the stream of people through the city was perceived as also good for the city. Immigrants were greeted with a positive eye. Immigration involves a steady movement of people from one place to another. -

The Immigrant Woman:Jewish Assimilation in the Lower East Side Ghetto of New York City, 1880-1914

Student Research History Theses University of Puget Sound Year 2012 The Immigrant Woman:Jewish Assimilation in the Lower East Side Ghetto of New York City, 1880-1914 Rachael Siegel [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/history theses/1 The Immigrant Woman: Jewish Assimilation in the Lower East Side Ghetto of New York City, 1880-1914 Rachael Siegel 12/14/2012 Siegel 1 “The last day of our journey comes vividly to my mind. Everybody was on deck…enraptured by the sight of the harbor and the Statue of Liberty suddenly emerging from the mist. Ah, there she was, the symbol of hope, of freedom, of opportunity! She held her torch high to light the way to the free country, the asylum for the oppressed of all lands. We too…would find a place in the generous heart of America. Our spirits were high, our eyes filled with tears.” 1 The United States was viewed as a beacon of hope for many Eastern European Jews who fled difficult lives. These people had experienced a history of poverty and pogroms in Eastern Europe. They were expelled from cities, their leaders were denied communal authority, and they faced many restrictions regarding occupation and the right to own land and real estate. 2 The tsarist autocracy, for example, confined its Jewish subjects to the Pale of Settlement, 3 and created poverty-stricken communities, called Shtetl, which were easy targets for pogroms and other legal restrictions.4 But the immigrants’ transition to life in to New York City was not easy. -

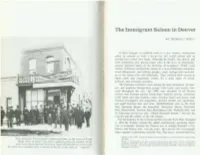

I the Immigrant Saloon in Denver

_I I I I ( The Immigrant Saloon in Denver l I BY THOMAS J. NOEL* In their struggle to establish roots in a new country, immigrants relied on saloons as both a haven for old world culture and an introduction to their new home. Although the family, the church, and r other institutions also played major roles in the lives of immigrants, r saloons sheltered many of the activities of foreigners. While some citizens of Denver attacked the saloon as a nest of political corruption, l moral debasement, and inferior peoples, many foreign-born newcom ers to the Queen City felt differently. They relished their taverns as ethnic clubs and community centers for a wide range of social, I political, and economic activities. ( The Germans in Denver were among the most prominent, prosper ous, and populous foreign-born groups with homes and taverns scat r tered throughout the city .1 By 1880 over one-third of all Denver saloons were German owned. Inside these Teutonic taverns , customers I could speak and sing German, enjoy German music and dance, read ( German newspapers and magazines, procure strudel and sauerkraut, [ and quaff German beer and wine. Establishments such as the Turn • Hall , Bavarian House, the Kaiserhof, Deutsches House, Germania I Hall , Mozart Hall, Saxonia Hall, Heidelberg Cafe, Walhalla Hall , and the Edelweiss served not only " Dutch (German) lunches" but also the l customs and the culture of the old country. ( The best known of the German taverns was the Turn Hall. Founded in 1865 the Turners remain the oldest continuously operating ethnic l club in Colorado. -

The Rise of New Immigrant Gateways Audrey Singer

Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy The Rise of New Immigrant Gateways Audrey Singer Findings “Traditional An analysis of immigration to metropolitan areas during the 20th century using U.S. Census data reveals that: gateways have ■ The U.S. foreign-born population grew 57.4 percent in the 1990s; by 2000 nearly one- third of U.S. immigrants resided outside established settlement states. Thirteen states primarily in the West and Southeast—including many that had not previously been major become former destinations for immigrants—saw foreign-born growth rates more than double the national average. These states included, Colorado, Georgia, Nevada, and North Carolina. gateways; new ■ Historical settlement patterns along with recent influxes of immigrants have produced six major types of U.S. immigrant “gateways.” Former gateways, like Cleveland and Buf- falo, attracted immigrants in the early 1900s but no longer do. Continuous gateways such gateways have as New York and Chicago are long-established destinations for immigrants and continue to receive large numbers of the foreign-born. Post-World War II gateways like Los Angeles and Miami began attracting immigrants on a grand scale during the past 50 years. Atlanta, emerged; and Dallas, and Washington, D.C., meanwhile, stand out as emerging gateways with fast immi- grant growth during the past 20 years. Seattle and the Twin Cities—places that began the 20th century with strong immigrant pulls—waned as destinations during the middle of the even newer century, but are now re-emerging as important immigrant gateways. Finally, Salt Lake City and Raleigh-Durham are very recent immigrant destinations, having attracted significant numbers of immigrants in the 1990s alone.