“Coming to America, 1880-1924.” Images and Information 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Were Jews Political Refugees Or Economic Migrants?

The New Comparative Economic History Essays in Honor of Jeffrey G. Williamson Edited by Timothy J. Hatton, I(evin H. O'Rourke, and Alan M. Taylor The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Were Jews Political Refugees or Economic Migrants? 11 Assessing the Persecution Theory of Jewish Emigration, 1881-1914 Leah Platt Boustan [11 1881, 4.1 Illillion Jews lived in the Russian empire. Over the next three decades, 1.5 million Russian Jews immigrated to the United States, and another 0.5 million left for other New World destinations, a mass migra tion surpassed in strength only by the Irish earlier in the century. Despite the intensity of Jewish migration, economic historians have paid lillle at tenlion to this episode. 1 This is clue, in pare to a lack of comparable data between Russia and the rest of continental Europe, but it also reilects the common belief that the exodus from Russia was a uniquely Jewish event and thus cannot be incorporated into a general model of migration as fac tor Bows. In this chapter, I argue that a confluence of demographic events, including population growth and internal migration from villages to larger cities, set the flow of Jewish migrants from Russia in motion. I fur ther demonstrate that the timing of Jewish migration, once it had begun in earnest, was influenced both by periodic religious violence and by busi ness cycles in the United States and Russia. Migration rates increased temporarily in the year after 11 documented persecution. In addition, by enlarging the slock of Jews living in the United States, many of whom joined emigrant aid societies or paid directly for their family's passage, temporary religious violence had modest long-run effects on the magni tude of the Jewish migration flow. -

GONE to TEXAS: PART of the NATION's IMMIGRATION STORY from the Bullock Texas State History Museum

GONE TO TEXAS: PART OF THE NATION'S IMMIGRATION STORY from the Bullock Texas State History Museum Children and Youth Bibliography (*denotes Galveston/Texas-focus) Elementary School Connor, Leslie illustrated by Mary Azarian. Miss Bridie Chose a Shovel. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. Miss Bridie embarks on a voyage to America in 1856. She chooses to bring along a shovel to start a new life in a new land. In this children's book, a young Irish woman's journey symbolizes the contribution made by millions of immigrants in building our nation. Freeman, Marilyn. Pasquale's Journey. New York University Press, 2003. Join Pasquale and his family on a journey from Italy to America. After receiving tickets from “Papa,” they start their long, exhausting voyage, all the time dreaming of a better life! Glasscock, Sarah. Read Aloud Plays: Immigration. Scholastic, 1999. This collection of plays will give students an opportunity to actively learn about Irish, Chinese, Lebanese, Cuban, and Russian Jews immigrating for a number of reasons. Herrera, Juan Felipe illustrated by Honorio Robledo Tapia. Super Cilantro Girl. Children's Book Press, 2003. This is a tale about a super-hero child who flies huge distances and scales tall walls in order to rescue her mom. Juan Felipe Herrera addresses and transforms the concerns many first-generation children have about national borders and immigrant status. Lawrence, Jacob. The Great Migration: An American Story. HarperCollins, 1995. This book chronicles the migration of African Americans from the South to replace workers because of WWI. It touches upon discrimination and sharecropping as well as the new opportunities of voting and going to school. -

Rabbi Henry Cohen and the Galveston Immigration Movement, 1907-1914

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 15 Issue 1 Article 8 3-1977 Rabbi Henry Cohen and the Galveston immigration Movement, 1907-1914 Ronald A. Axelrod Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Axelrod, Ronald A. (1977) "Rabbi Henry Cohen and the Galveston immigration Movement, 1907-1914," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 15 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol15/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 24 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION RABBI HENRY COHEN AND THE GALVESTON IMMIGRATION MOVEMENT* 1907-1914 By Ronald A. Axelrod The role men and women play in history can be viewed from two perspec tives. Either men determine history by their actions or history determines the actions of men. At times a combination of the two may take place. The relationship of Rabbi Henry Cohen 0863-1952) of Galveston and the Galves ton Immigration Movement, often called the Galveston Plan, was a case of combining these two historical perspectives. The necessity of a nation and a religious group to change its immigration patterns coupled with the extra ordinary humanitarian efforts of a great man created the product of an innova tive, well-planned program. This paper will examine the workings of the Galveston Plan and the role Henry Cohen played in making that plan a partial success. -

History of the Jews

II ADVERTISEMENTS Should be in Every Jewish Home AN EPOCH-MAKING WORK COVERING A PERIOD OF ABOUT FOUR THOUSAND YEARS PROF. HE1NRICH GRAETZ'S HISTORY OF THE JEWS THE MOST AUTHORITATIVE AND COMPREHENSIVE HISTORY OF THE JEWS IN THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE HANDSOMELY AND DURABLY BOUND IN SIX VOLUMES Contains more than 4000 pages, a Copious Index of more than 8000 Subjects, and a Number of Good Sized Colored Maps. SOME ENTHUSIASTIC APPRECIATIONS DIFFICULT TASK PERFORMED WITH CONSUMMATE SKILL "Graetz's 'Geschichte der Juden1 has superseded all former works of its kind, and has been translated into English, Russian and Hebrew, and partly into Yiddish and French. That some of these translations have been edited three or four times—a very rare occurrence in Jewish literature—are in themselves proofs of the worth of the work. The material for Jewish history being so varied, the sources so scattered in the literatures of all nations, made the presentation of this history a very difficult undertaking, and it cannot be denied that Graetz performed his task with consummate skill."—The Jewish Encyclopedia. GREATEST AUTHORITY ON SUBJECT "Professor Graetz is the historiographer par excellence of the Jews. His work, at present the authority upon the subject of Jewish History, bids fair to hold its pre-eminent position for some time, perhaps decades."—Preface to Index Volume. MOST DESIRABLE TEXT-BOOK "If one desires to study the history of the Jewish people under the direction of a scholar and pleasant writer who is in sympathy with his subject, because he is himself a Jew, he should resort to the volumes of Graetz."—"Review ofRevitvit (New York). -

A Study in American Jewish Leadership

Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page i Jacob H. Schiff Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page ii blank DES: frontis is eps from PDF file and at 74% to fit print area. Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page iii Jacob H. Schiff A Study in American Jewish Leadership Naomi W. Cohen Published with the support of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America and the American Jewish Committee Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page iv Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, Hanover, NH 03755 © 1999 by Brandeis University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 54321 UNIVERSITY PRESS OF NEW ENGLAND publishes books under its own imprint and is the publisher for Brandeis University Press, Dartmouth College, Middlebury College Press, University of New Hampshire, Tufts University, and Wesleyan University Press. library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Cohen, Naomi Wiener Jacob H. Schiff : a study in American Jewish leadership / by Naomi W. Cohen. p. cm. — (Brandeis series in American Jewish history, culture, and life) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-87451-948-9 (cl. : alk. paper) 1. Schiff, Jacob H. (Jacob Henry), 1847-1920. 2. Jews—United States Biography. 3. Jewish capitalists and financiers—United States—Biography. 4. Philanthropists—United States Biography. 5. Jews—United States—Politics and government. 6. United States Biography. I. Title. II. Series. e184.37.s37c64 1999 332'.092—dc21 [B] 99–30392 frontispiece Image of Jacob Henry Schiff. American Jewish Historical Society, Waltham, Massachusetts, and New York, New York. -

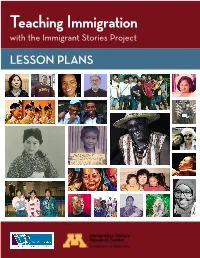

Teaching Immigration with the Immigrant Stories Project LESSON PLANS

Teaching Immigration with the Immigrant Stories Project LESSON PLANS 1 Acknowledgments The Immigration History Research Center and The Advocates for Human Rights would like to thank the many people who contributed to these lesson plans. Lead Editor: Madeline Lohman Contributors: Elizabeth Venditto, Erika Lee, and Saengmany Ratsabout Design: Emily Farell and Brittany Lynk Volunteers and Interns: Biftu Bussa, Halimat Alawode, Hannah Mangen, Josefina Abdullah, Kristi Herman Hill, and Meredith Rambo. Archival Assistance and Photo Permissions: Daniel Necas A special thank you to the Immigration History Research Center Archives for permitting the reproduction of several archival photos. The lessons would not have been possible without the generous support of a Joan Aldous Diversity Grant from the University of Minnesota’s College of Liberal Arts. Immigrant Stories is a project of the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota. This work has been made possible through generous funding from the Digital Public Library of America Digital Hubs Pilot Project, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. About the Immigration History Research Center Founded in 1965, the University of Minnesota's Immigration History Research Center (IHRC) aims to transform how we understand immigration in the past and present. Along with its partner, the IHRC Archives, it is North America's oldest and largest interdisciplinary research center and archives devoted to preserving and understanding immigrant and refugee life. The IHRC promotes interdisciplinary research on migration, race, and ethnicity in the United States and the world. It connects U.S. immigration history research to contemporary immigrant and refugee communities through its Immigrant Stories project. -

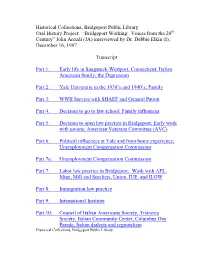

Interview with John Arcudi, by Debbie Elkin, for the Bridgeport Public

Historical Collections, Bridgeport Public Library Oral History Project: “Bridgeport Working: Voices from the 20th Century” John Arcudi (JA) interviewed by Dr. Debbie Elkin (I), December 16, 1997 Transcript Part 1: Early life in Saugatuck-Westport, Connecticut; Italian American family; the Depression Part 2: Yale University in the 1930’s and 1940’s; Family Part 3: WWII Service with SHAEF and General Patton Part 4: Decision to go to law school; Family influences Part 5: Decision to open law practice in Bridgeport; Early work with unions; American Veterans Committee (AVC) Part 6: Political influences at Yale and from home experience; Unemployment Compensation Commission Part 7a: Unemployment Compensation Commission Part 7: Labor law practice in Bridgeport; Work with AFL, Mine, Mill and Smelters, Union, IUE, and ILGW Part 8: Immigration law practice Part 9: International Institute Part 10: Council of Italian Americans Society, Triancria Society, Italian Community Center, Columbus Day Parade, Italian dialects and regionalism Historical Collections, Bridgeport Public Library Oral History Project: “Bridgeport Working: Voices from the 20th Century” John Arcudi (JA) interviewed by Dr. Debbie Elkin (I), December 16, 1997 I: Would you mind saying your name for the tape? JA: John Arcudi. I: Thank you. Would you mind telling me something about your childhood? JA: Well, I was born in Westport, Connecticut and educated in the Westport Public Schools. My parents -- we lived above a grocery and meat market that my parents ran. Born May 26, 1921, whatever that means. I graduated from Staples High School in 1938. I went to Yale and graduated Yale, with a major in Economics, in 1942, did a term of law school, went off to war, served in the U.S. -

Facing the Sea: the Jews of Salonika in the Ottoman Era (1430–1912)

Facing the Sea: The Jews of Salonika in the Ottoman Era (1430–1912) Minna Rozen Afula, 2011 1 © All rights reserved to Minna Rozen 2011 No part of this document may be reproduced, published, stored in an electronic database, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, for any purpose, without the prior written permission of the author ([email protected]). 2 1. Origins, Settlement and Heyday, 1430–1595 Jews resided in Salonika many centuries before the Turkic tribes first made their appearance on the borders of Western civilization, at the Islamic world’s frontier. In fact, Salonika was one of the cities in whose synagogue the apostle Paul had preached Jesus’ teachings. Like many other Jewish communities is this part of the Roman (and later the Byzantine) Empire, this had been a Greek-speaking community leading its life in much the same way as the Greek pagans, and later, the Christian city dwellers around them. The Ottoman conquest of Salonika in 1430 did little to change their lifestyle. A major upheaval did take place, however, with the Ottoman takeover of Constantinople in 1453. The Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II, the Conqueror (Fatih in Turkish), aimed to turn the former Byzantine capital into the hub of his Empire, a world power in its own right on a par with such earlier grand empires as the Roman and the Persian. To that effect, he ordered the transfer of entire populations— Muslims, Greeks, and Jews—from other parts of his empire to the new capital in order to rebuild and repopulate it. -

The Project of the Baron De Hirsch. Success Or Failure?

THE PROJECT OF THE BARON DE HIRSCH. SUCCESS OR FAILURE? EDGARDO ZABLOTSKY∗ MAY 2005 ABSTRACT In 1891, Baron Maurice de Hirsch founded the Jewish Colonization Association (J.C.A.), through which he would manage a gigantic social welfare project concerning the immigration of thousands of people from the Russian Empire towards Argentina, and their settlement in agricultural colonies. In this paper, we evaluate the result of this project, which is generally qualified as a failure by historians on the subject. We hold an alternative hypothesis, wholly opposed to this conclusion: if the social evaluation of the project were carried out, taking into account the externality it generated, the conclusion would be that the project was highly successful; even though its private evaluation ,which implicitly is the usually made evaluation, would lead to the conclusion that it was a total failure. This externality is reflected in the number of immigrants arriving in the country independently of the J.C.A., but who would have never come here were it not be for Baron de Hirsch’s project, since it placed Argentina on the map of East European Jewry, in a world in which the dissemination of information was slow and deficient. JEL classification codes: I38, N96 Key words: Externalities, Baron Maurice de Hirsch, Jewish Colonization Association ∗ University of CEMA, Av. Córdoba 374 (1054) Buenos Aires, Argentina. Email: [email protected]. The author wants to thank Susana Sigwald Carioli for introducing me to the history of Colonia Mauricio, Carlos Galperín and Carlos Rodríguez for their suggestions, Martín Monastirsky for its efficient assistance, and Patricia Allendez Sullivan for her efficient work in tracing bibliography. -

Chemins De Fer Orientaux 1867-1883 Prelude 2 of 20

ORIENT EXPRESS 1 OF 10 Prelude Chemins de fer Orientaux 1867-1883 PRELUDE 2 OF 20 Prelude 1867-1883 The genesis of the Orient Express — a direct luxury train service between Paris and Constantinople — cannot be attributed to a single person or organization. Several historical developments coincided. After a train trip through Europe, Sultan Abdülaziz decided that Constantinople should be linked to the West by rail. This plan was carried out by Baron Maurice de Hirsch and his Chemins de fer Orientaux. Meanwhile in the US, George Pullman developed the luxury sleeper car that enabled overnight train travel. The Belgian Georges Nagelmackers introduced this concept in Europe. Requirements Still, not all the requirements had been fulfilled. A consultative body was needed to make the highly fragmented European railway companies work together. The first International Timetable Conference took place in 1872, the same year that Nagelmackers introduced his first Wagons-Lits and the first train entered Constantinople. But it would take over 10 years before the Orient Express could be launched. PRELUDE 3 VAN 20 Constantinople and the Bosporus 1862 A journey to Constantinople over the Mediterranean or via the Danube and Black Sea took at least one week. PRELUDE 4 OF 20 The Sultan's tour 1867 In 1867 Abdülaziz was the first Ottoman sultan to travel through Europe. He visited the Paris World Exhibition, was received with ceremony in London and visited Brussels, Berlin and Vienna on his way. He mostly traveled in his own imperial railway carriage. For centuries, the Ottoman Empire had been a closed bastion. From 1840 onwards sultan Abdülmecid carried through reforms. -

Immigration and Immigrants

IMMIGRATION AND IMMIGRANTS SETTING THE RECORD STRAIGHT MICHAEL FIX AND JEFFREY S. PASSEL with María E. Enchautegui and Wendy Zimmermann May 1994 THE URBAN INSTITUTE • WASHINGTON, D.C. i THE URBAN INSTITUTE is a nonprofit, nonpartisan policy research organization established in Washington, D.C., in 1968. Its staff investigates the social and economic problems confronting the nation and assesses public and private means to alleviate them. The Institute seeks to sharpen thinking about society’s problems and efforts to solve them, improve government decisions and performance, and increase citizen awareness about important public choices. Through work that ranges from broad conceptual studies to administrative and technical assistance, Institute researchers contribute to the stock of knowledge available to guide decisionmaking in the public interest. In recent years this mission has expanded to include the analysis of social and economic problems and policies in developing coun- tries and in the emerging democracies of Eastern Europe. Immigrant Policy Program The Urban Institute’s Immigrant Policy Program was created in 1992 with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The overall goal of the program is to research, design, and promote policies that integrate newcomers into the United States. To that end, the program seeks to: 1) Develop systematic knowledge on immigrants’ economic mobility and social integration, and the public policies that influence them; 2) Disseminate knowledge broadly to government agencies, non- profit organizations, scholars, and the media; and 3) Advise policymakers on the merits of current and proposed policies. Program for Research on Immigration Policy The Program for Research on Immigration Policy was established in 1988 with ini- tial core support from The Ford Foundation. -

THE LIPTON JEWISH AGRICULTURAL COLONY 1901-1951 by Theodore H

JEWISH PIONEERS ON CANADA’S PRAIRIES: THE LIPTON JEWISH AGRICULTURAL COLONY 1901-1951 By Theodore H. Friedgut Department of Russian and Slavic Studies Hebrew University of Jerusalem JEWISH PIONEERS ON CANADA’S PRAIRIES: THE LIPTON JEWISH AGRICULTURAL COLONY INTRODUCTION What would bring Jews from the Russian Empire and Rumania, a population that on the whole had long been separated from any agricultural life, to undertake a pioneering farm life on Canada’s prairies? Equally interesting is the question as to what Canada’s interest was in investing in the settlement of Jews, most totally without agricultural experience, in the young Dominion’s western regions? Jewish agricultural settlement in Western Canada was only one of several such projects, and far from the largest. Nevertheless it is an important chapter in the development of the Canadian Jewish community, as well as providing interesting comparative material for the study of Jewish agricultural settlement in Russia (both pre and post revolution), in Argentina, and in the Land of Israel. In this monograph, we present the reader with a detailed exposition and analysis of the political, social, economic and environmental forces that molded the Lipton colony in its fifty-year existence as one of several dozen attempts to plant Jewish agricultural colonies on Canada’s Western prairies. By comparing both the particularities and the common features of Lipton and some other colonies we may be able to strengthen some of the commonly accepted generalizations regarding these colonies, while at the same time marking other assumptions as questionable or even perhaps, mythical.1 In our conclusions we will suggest that after a half century of vibrant cultural, social and economic life, the demise of Lipton and of the Jewish agricultural colonies in general was largely because of the state of Saskatchewan’s agriculture as a chronically depressed industry.