Cancer Productus Class: Multicrustacea, Malacostraca, Eumalacostraca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning in Stomatopod Crustaceans

International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2006, 19 , 297-317. Copyright 2006 by the International Society for Comparative Psychology Learning in Stomatopod Crustaceans Thomas W. Cronin University of Maryland Baltimore County, U.S.A. Roy L. Caldwell University of California, Berkeley, U.S.A. Justin Marshall University of Queensland, Australia The stomatopod crustaceans, or mantis shrimps, are marine predators that stalk or ambush prey and that have complex intraspecific communication behavior. Their active lifestyles, means of predation, and intricate displays all require unusual flexibility in interacting with the world around them, imply- ing a well-developed ability to learn. Stomatopods have highly evolved sensory systems, including some of the most specialized visual systems known for any animal group. Some species have been demonstrated to learn how to recognize and use novel, artificial burrows, while others are known to learn how to identify novel prey species and handle them for effective predation. Stomatopods learn the identities of individual competitors and mates, using both chemical and visual cues. Furthermore, stomatopods can be trained for psychophysical examination of their sensory abilities, including dem- onstration of color and polarization vision. These flexible and intelligent invertebrates continue to be attractive subjects for basic research on learning in animals with relatively simple nervous systems. Among the most captivating of all arthropods are the stomatopod crusta- ceans, or mantis shrimps. These marine creatures, unfamiliar to most biologists, are abundant members of shallow marine ecosystems, where they are often the dominant invertebrate predators. Their common name refers to their method of capturing prey using a folded, anterior raptorial appendage that looks superficially like the foreleg of a praying mantis. -

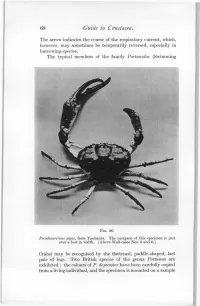

68 Guide to Crustacea

68 Guide to Crustacea. The arrow indicates the course of the respiratory current, which, however, may sometimes be temporarily reversed, especially in burrowing species. The typical members of the family Portunidae (Swimming FIG. 46. Pseudocarcinus gigas, from Tasmania. The carapace of this specimen is just over a foot in width. [Above Wall-cases Nos. 5 and 6.] Crabs) may be recognised by the flattened, paddle-shaped, last pair of legs. Two British species of the genus Portunus are exhibited : the colours of P. depurator have been carefully copied from a living individual, and the specimen is mounted on a sample Decapoda—Brachyura. 69 of the shell-gravel on which it was actually caught. The large Neptunus pelagicus is the commonest edible Crab in many parts of the East. The Common Shore Crab, Carcinus maenas, is also referred to this family, although the paddle-shape of the last legs is not so marked as in the more typical Portunidae. Podophthalmus vigil (Fig. 47) is remarkable for the great length of the eye-stalks, which is quite unusual among the Cyclometopa, and gives this Crab a curious likeness to the genus Macrophthalmus among the Ocypodidae (see Table-case No. 16). The resemblance, however, is quite superficial, for in this case FIG. 47. Podophthalmus vigil (reduced). [Table-case No. 15.] it is the first of the two segments of the eye-stalk which is elongated, while in Macrophthalmus it is the second. The genus Platyonychus, of which a group of specimens is mounted in Wall-case No. 5, also belongs to this family. -

DINÂMICA POPULACIONAL DO SIRI-AZUL Callinectes Sapidus (RATHBUN, 1896) (CRUSTACEA: DECAPODA: PORTUNIDAE) NO BAIXO ESTUÁRIO DA LAGOA DOS PATOS, RS, BRASIL

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM OCEANOGRAFIA BIOLÓGICA DINÂMICA POPULACIONAL DO SIRI-AZUL Callinectes sapidus (RATHBUN, 1896) (CRUSTACEA: DECAPODA: PORTUNIDAE) NO BAIXO ESTUÁRIO DA LAGOA DOS PATOS, RS, BRASIL LEONARDO SIMÕES FERREIRA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós- graduação em Oceanografia Biológica da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de DOUTOR. Orientador: Fernando D´Incao RIO GRANDE Janeiro/2012 AGRADECIMENTOS Em primeiro lugar ao meu amigo, professor e orientador Dr. Fernando D´Incao, por seus ensinamentos durante todos esses anos. Ao meu coorientador e amigo Dr. Duane Fonseca, por toda ajuda no decorrer da Tese, e principalmente por me passar todo o seu conhecimento sobre o assunto “lipofuscina”. Aos Doutores, Paulo Juarez Rieger, Enir Girondi Reis (Neca), Wilson Wasieleski (Mano), e Rogério Caetano (Cebola) da Unespe, por aceitarem fazer parte da minha banca examinadora, e por suas valiosas correções e sugestões. Toda a galera do Laboratório de Crustáceos Decapodes, os quais são muitos! A minha amiga especial Laboratorista/Dra. Roberta Barutot que me ajudou em grande parte da Tese, assim como o Doutor Luiz Felipe Dumont. Aos meus estagiários, Andréia Barros, Renan (bonitão.com) e Diego Martins (guasco). Meus amigos pescadores: Pingo, Sarinha, Leandro, Giovani e Didico. A minha família, meus pais, minha esposa Juliana e a minha princesinha Luana! Ao Programa de Pós-graduação em Oceanografia Biológica, a Capes pela concessão da bolsa de estudos, ao Instituto de -

Circadian Clocks in Crustaceans: Identified Neuronal and Cellular Systems

Circadian clocks in crustaceans: identified neuronal and cellular systems Johannes Strauss, Heinrich Dircksen Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, Svante Arrhenius vag 18A, S-10691 Stockholm, Sweden TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Abstract 2. Introduction: crustacean circadian biology 2.1. Rhythms and circadian phenomena 2.2. Chronobiological systems in Crustacea 2.3. Pacemakers in crustacean circadian systems 3. The cellular basis of crustacean circadian rhythms 3.1. The retina of the eye 3.1.1. Eye pigment migration and its adaptive role 3.1.2. Receptor potential changes of retinular cells in the electroretinogram (ERG) 3.2. Eyestalk systems and mediators of circadian rhythmicity 3.2.1. Red pigment concentrating hormone (RPCH) 3.2.2. Crustacean hyperglycaemic hormone (CHH) 3.2.3. Pigment-dispersing hormone (PDH) 3.2.4. Serotonin 3.2.5. Melatonin 3.2.6. Further factors with possible effects on circadian rhythmicity 3.3. The caudal photoreceptor of the crayfish terminal abdominal ganglion (CPR) 3.4. Extraretinal brain photoreceptors 3.5. Integration of distributed circadian clock systems and rhythms 4. Comparative aspects of crustacean clocks 4.1. Evolution of circadian pacemakers in arthropods 4.2. Putative clock neurons conserved in crustaceans and insects 4.3. Clock genes in crustaceans 4.3.1. Current knowledge about insect clock genes 4.3.2. Crustacean clock-gene 4.3.3. Crustacean period-gene 4.3.4. Crustacean cryptochrome-gene 5. Perspective 6. Acknowledgements 7. References 1. ABSTRACT Circadian rhythms are known for locomotory and reproductive behaviours, and the functioning of sensory organs, nervous structures, metabolism and developmental processes. The mechanisms and cellular bases of control are mainly inferred from circadian phenomenologies, ablation experiments and pharmacological approaches. -

Cherax Murido (A Crayfish, No Common Name) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Cherax murido (a crayfish, no common name) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, September 2011 Revised, September 2012, December 2017 Web Version, 5/17/2017 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Crandall and De Grave (2017): “ ‘Paniai Lake’ [Papua Province, Indonesia]” Status in the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the United States. No evidence was found of trade of C. murido in the United States. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has listed the crayfish Cherax murido as a prohibited species. Prohibited nonnative species “are considered to be dangerous to the ecology and/or the health and welfare of the people of Florida. These species are not allowed to be personally possessed or used for commercial activities” (FFWCC 2017). From Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife (2017): “(1) Prohibited aquatic animal species. RCW 77.12.020 1 These species are considered by the commission to have a high risk of becoming an invasive species and may not be possessed, imported, purchased, sold, propagated, transported, or released into state waters except as provided in RCW 77.15.253. […] The following species are classified as prohibited animal species: […] Family Parastacidae: Crayfish: All genera except Engaeus, and except the species Cherax quadricarninatus [sic], Cherax papuanus, and Cherax tenuimanus.” Means of Introduction into the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the United States. 2 Biology and Ecology Taxonomic Hierarchy and Taxonomic Standing From Crandall (2016): “Classification: Animalia (Kingdom) > Arthropoda (Phylum) > Crustacea (Subphylum) > Multicrustacea (Superclass) > Malacostraca (Class) > Eumalacostraca (Subclass) > Eucarida (Superorder) > Decapoda (Order) > Pleocyemata (Suborder) > Astacidea (Infraorder) > Parastacoidea (Superfamily) > Parastacidae (Family) > Cherax (Genus) > Cherax murido (Species)” “Status: accepted” Size, Weight, and Age Range No information available. -

Seasonal Movements and Distribution of Dungeness Crabs Cancer Magister in a Glacial Southeastern Alaska Estuary

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 214: 167–176, 2001 Published April 26 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Seasonal movements and distribution of Dungeness crabs Cancer magister in a glacial southeastern Alaska estuary Robert P. Stone*, Charles E. O’Clair Auke Bay Laboratory, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 11305 Glacier Highway, Juneau, Alaska 99801, USA ABSTRACT: The movements of 10 female and 8 male adult Dungeness crabs, Cancer magister (Dana, 1852), were monitored biweekly to monthly with ultrasonic biotelemetry for periods ranging from 73 to 555 d. Female and male crabs had different seasonal patterns of habitat use, depth distri- bution, and activity. The general pattern for female crabs was: (1) a relatively inactive period between November and mid-April at depths below 20 m; ovigerous crabs were typically buried dur- ing this period in a dense aggregation; (2) abrupt movement into shallow water (<8 m) in late April and residence there until early June; this movement was coincident with the spring phytoplankton bloom and initiation of larval hatching; (3) increased activity beginning in July with movement back to deeper water, presumably to forage. Females that molted prior to oviposition did so in June and July. Male crabs occupied deep water (>40 m) from November to April, then concentrated in shallow water (<25 m), segregated from females, until late July. Males were most active in late summer and moved into deeper water (>30 m) near the mouth of the cove in fall. The range of depths were –0.5 to –61.3 m for females and +0.1 to –89.0 m for males. -

Dungeness Crab (Cancer Magister) Fishery

STATE OF WASHINGTON December 2008 Management Recommendations for Washington’s Priority Habitats and Species Dungeness Crab illustration courtesy of California Department of Fish and Game Dungeness Crab Cancer magister By Wendy Fisher and Donald Velasquez Washington Department of FISH AND WILDLIFE GENERAL RANGE AND WASHINGTON DISTRIBUTION Dungeness Crabs (Cancer magister) are found in the coastal marine and estuarine waters of the northeastern Pacific Ocean from the Pribilof Islands, Alaska, to Santa Barbara, California (Jensen 1995). In Washington, Dungeness Crabs live in all marine waters, bays, and estuaries, including Willapa Bay, Grays Harbor, and Puget Sound (Figure 1). Within Puget Sound, they are most abundant in the waters north of Seattle, somewhat abundant in Hood Canal, and much less abundant in southern Puget Sound (Bumgarner 1990). RATIONALE The ecological requirements of Dungeness Crabs make them vulnerable to decline. This species is more susceptible to population impacts from harvest, disease, and dredging in areas where it concentrates for mating and egg incubation. It is also susceptible to mortality when caught in derelict fishing Figure 1. Washington’s distribution of gear (e.g., lost or abandoned crab pots and gillnets). Dungeness Crab. Dungeness Crab is included as a priority species in Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (WDFW’s) Priority Habitats and Species List (PHS List). They are an important resource for recreational, commercial and tribal harvests. Co-managed by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and Washington’s Treaty Tribes, Washington’s commercial harvest ranked first among all Pacific states and provinces between 2000 and 2004 (Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission data). -

Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-17-2017 Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality Brian Christopher Turner Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Turner, Brian Christopher, "Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality" (2017). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3620. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5512 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality by Brian Christopher Turner A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Sciences and Resources Dissertation Committee: Catherine E. de Rivera, Chair Edwin D. Grosholz Michael T. Murphy Greg M. Ruiz Ian R. Waite Portland State University 2017 Abstract Lethal biotic interactions strongly influence the potential for aquatic non-native species to establish and endure in habitats to which they are introduced. Predators in the recipient area, including native and previously established non-native predators, can prevent establishment, limit habitat use, and reduce abundance of non-native species. Management efforts by humans using methods designed to cause mass mortality (e.g., trapping, biocide applications) can reduce or eradicate non-native populations. -

Distribution, Abundance, and Diversity of Epifaunal Benthic Organisms in Alitak and Ugak Bays, Kodiak Island, Alaska

DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND DIVERSITY OF EPIFAUNAL BENTHIC ORGANISMS IN ALITAK AND UGAK BAYS, KODIAK ISLAND, ALASKA by Howard M. Feder and Stephen C. Jewett Institute of Marine Science University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 Final Report Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Research Unit 517 October 1977 279 We thank the following for assistance during this study: the crew of the MV Big Valley; Pete Jackson and James Blackburn of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Kodiak, for their assistance in a cooperative benthic trawl study; and University of Alaska Institute of Marine Science personnel Rosemary Hobson for assistance in data processing, Max Hoberg for shipboard assistance, and Nora Foster for taxonomic assistance. This study was funded by the Bureau of Land Management, Department of the Interior, through an interagency agreement with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Department of Commerce, as part of the Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Environment Assessment Program (OCSEAP). SUMMARY OF OBJECTIVES, CONCLUSIONS, AND IMPLICATIONS WITH RESPECT TO OCS OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT Little is known about the biology of the invertebrate components of the shallow, nearshore benthos of the bays of Kodiak Island, and yet these components may be the ones most significantly affected by the impact of oil derived from offshore petroleum operations. Baseline information on species composition is essential before industrial activities take place in waters adjacent to Kodiak Island. It was the intent of this investigation to collect information on the composition, distribution, and biology of the epifaunal invertebrate components of two bays of Kodiak Island. The specific objectives of this study were: 1) A qualitative inventory of dominant benthic invertebrate epifaunal species within two study sites (Alitak and Ugak bays). -

Series Eumalacostraca

Series Eumalacostraca Dr. Amrutha Gopan Assistant Professor School of Fisheries Centurion University of Technology and Management Odisha Sub-class 8. Malacostraca Large sized, Marine and freshwater crustaceans. Body distinctly segmented, usually with a head made of 5 somites, a thorax of 8 somites and an abdomen of 6 somites. Carapace may be present, vestigial or absent. Exoskeleton of head united with few or more thoracic segments to form cephalothoracic carapace. Appendages typically 19 pairs, 13 cephalothoracic 6 abdominal Compound eyes; paired; stalked or sessile. Antennules often biramous. Abdominal caudal style absent; terminates in a telson. Female gonopore on 6th thoracic segment, male on 8th. Young hatching out of the egg is zoea, rarely a nauplius. Sub-class 8. Malacostraca This sub-class includes commercially important crustaceans and hence classification of this class is described in detail. This sub-class includes 2 series, 4 divisions and a large number of orders. Series 1- Leptostraca Series 2- Eumalacostraca Series 1. Leptostraca Marine crustaceans; highly primitive with 21 body segments. Body made up of 21 segments, abdomen of 7 segments. Thoracic appendages similar and foliaceous; eyes stalked Telson has a pair of caudal styles or furcal rami. Eg. Nebalia Series 2. Eumalacostraca Marine, freshwater or terrestrial malacostracans with 20 body segments. Abdomen of 6 or fewer somites. Thoracic appendages typically leg-like. Telson without caudal styles. Eyes sessile or stalked Super-order 1. Syncarida Super-order 2. Peracarida Super-order 3. Hoplocarida Super-order 4. Eucarida Super-order 1. Syncarida Carapace absent. This super order consist two orders. Order 1. Anaspidacea First thoracic segment fused with head. -

Atlantic Rock Crab, Jonah Crab US Atlantic

Atlantic rock crab, Jonah crab Cancer irroratus, Cancer borealis Image ©Scandinavian Fishing Yearbook / www.scandfish.com US Atlantic Trap May 12, 2016 Gabriela Bradt, Consulting researcher Neosha Kashef, Consulting Researcher Sam Wilding, Seafood Watch Senior Fisheries Scientist Disclaimer: Seafood Watch® strives to have all Seafood Reports reviewed for accuracy and completeness by external scientists with expertise in ecology, fisheries science and aquaculture. Scientific review, however, does not constitute an endorsement of the Seafood Watch® program or its recommendations on the part of the reviewing scientists. Seafood Watch® is solely responsible for the conclusions reached in this report. 2 Table of Contents About Seafood Watch® ................................................................................................................................. 3 Guiding Principles ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Summary ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Assessment ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Criterion 1: Impact on the Species Under -

Red Rock Crab in the Coos Estuary

Red Rock Crab in the Coos Estuary Summary: The population of red rock crab appears stable in the Coos estuary but more data are needed to understand the population dynamics of this Adult species. Red Rock Crab Juvenile Red Rock Crab per day. Despite this, scientists think red rock crab populations may be relatively stable in the Coos estuary. Preliminary results from a crab tagging study by Groth et al. (2013) Location of red rock show relative stability in Coos Bay’s red rock crab study sites. crab’s size distributions compared with those What’s happening? of Dungeness crab, though Groth urges caution on this point because the results may Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife simply be highlighting red rock crab’s high (ODFW) regulates the harvest of red rock site fidelity (S. Groth, pers. comm., 2014). He crab (Cancer productus) less rigorously than also found that all red rock crab age classes Dungeness crab, allowing any size or sex to are found year round within the estuary, be taken and a limit of 24 crabs per person Crabs in the Coos Estuary 14-19 which differs from Dungeness crabs (larger Distribution in the Coos Estuary Red rock crabs do not burrow and tend crabs are found inside the estuary in the fall to avoid sandy substrates as they lack any Red rock crab adults are found among rocks and smaller crabs in the spring and summer) straining apparatus for sand removal (Rudy and hard bottom substrates. They’re found (Figure 1). This work suggests, at minimum, et al.