Robert Walsh's an Appeal from the Judgments of Great Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Ralph Ingersoll Collection #113

The Inventory of the Ralph Ingersoll Collection #113 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center John Ingersoll 1625-1684 Bedfordshire, England Jonathan Ingersoll 1681-1760 Connecticut __________________________________________ Rev. Jonathan Ingersoll Jared Ingersoll 1713-1788 1722-1781 Ridgefield, Connecticut Stampmaster General for N.E Chaplain Colonial Troops Colonies under King George III French and Indian Wars, Champlain Admiralty Judge Grace Isaacs m. Jonathan Ingersoll Baron J.C. Van den Heuvel Jared Ingersoll, Jr. 1770-1823 1747-1823 1749-1822 Lt. Governor of Conn. Member Const. Convention, 1787 Judge Superior and Supreme Federalist nominee for V.P., 1812 Courts of Conn. Attorney General Presiding Judge, District Court, PA ___ _____________ Grace Ingersoll Charles Anthony Ingersoll Ralph Isaacs Ingersoll m. Margaret Jacob A. Charles Jared Ingersoll Joseph Reed Ingersoll Zadock Pratt 1806- 1796-1860 1789-1872 1790-1878 1782-1862 1786-1868 Married General Grellet State=s Attorney, Conn. State=s Attorney, Conn. Dist. Attorney, PA U.S. Minister to England, Court of Napoleon I, Judge, U.S. District Court U.S. Congress U.S. Congress 1850-1853 Dept. of Dedogne U.S. Minister to Russia nom. U.S. Minister to under Pres. Polk France Charles D. Ingersoll Charles Robert Ingersoll Colin Macrae Ingersoll m. Julia Helen Pratt George W. Pratt Judge Dist. Court 1821-1903 1819-1903 New York City Governor of Conn., Adjutant General, Conn., 1873-77 Charge d=Affaires, U.S. Legation, Russia, 1840-49 Theresa McAllister m. Colin Macrae Ingersoll, Jr. Mary E. Ingersoll George Pratt Ingersoll m. Alice Witherspoon (RI=s father) 1861-1933 1858-1948 U.S. Minister to Siam under Pres. -

Alexander Hill Everett, Ou L'artisan Américain D'une Identité Cubaine

Alexander Hill Everett, ou l’artisan américain d’une identité cubaine. (Axe IV, Symposium 16) Rahma Jerad To cite this version: Rahma Jerad. Alexander Hill Everett, ou l’artisan américain d’une identité cubaine. (Axe IV, Sympo- sium 16). Independencias - Dependencias - Interdependencias, VI Congreso CEISAL 2010, Jun 2010, Toulouse, France. halshs-00502328 HAL Id: halshs-00502328 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00502328 Submitted on 20 Jul 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Rahma Jerad Université Paris I – Panthéon Sorbonne/ LARCA CEISAL « Dépendances, Indépendances, Interdépendances » Alexander Hill Everett, ou l'artisan américain d'une identité cubaine Résumé: A partir du dix-huitième siècle, pour des raisons idéologiques, stratégiques et économiques, l'île de Cuba était dans la ligne de mire de la jeune république américaine, dont les dirigeants et la population rêvaient d'étendre le territoire sur le continent et au-delà. Les Etats-Unis ont usé nombre de stratagèmes pour devenir les heureux propriétaires de ce splendide joyau, des propositions d'achat aux pressions diplomatiques pour en éloigner les grandes puissances européennes en passant par les campagnes de propagande dans la presse. -

(1826-1846) / Salvador García

Salvador García Castañeda Presencia de Washington Irving y otros norteamericanos en la España Romántica (1826-1846) Boletín de la Biblioteca de Menéndez Pelayo. LXXXVII, 2011, 113-126 PRESENCIA DE WASHINGTON IRVING Y OTROS NORTEAMERICANOS EN LA ESPAÑA ROMÁNTICA (1826-1846)* ashington Irving es el representante más destacado, y el más conocido entre nos- otros, de la atracción que ejerció España sobre un considerable grupo de norte- Wamericanos quienes a lo largo del siglo XIX dejaron profunda huella de sus experiencias en la cultura de su país. Una huella manifiesta en libros de viajes, en traba- jos históricos y literarios, en la creación de bibliotecas y de colecciones de obras de arte, en el extraordinario auge de los estudios universitarios de la lengua, la cultura y la litera- tura españolas en los Estados Unidos y, finalmente, en difundir el conocimiento de España en aquel país. Esta conferencia tiene el carácter de una visión de conjunto pues me pro- pongo referirme a temas tan amplios como el magisterio y huella de Washington Irving y otros hispanófilos norteamericanos de la primera mitad del XIX sobre la literatura de su país en el momento de transición de la Ilustración al Romanticismo, así como a su deci- siva influencia sobre la difusión de los estudios universitarios del español en los Estados Unidos. Me he marcado tentativamente las fechas de 1826 a 1846 por ser respectivamente la de la primera visita a España del Washington Irving autor de Los cuentos de la Alham- bra, y la de la última como representante diplomático de su país. En aquellos años la vida cultural, política y económica norteamericana estaba con- centrada principalmente en Nueva Inglaterra, al Este del país, y principalmente en Fila- delfia, que fue la primera capital de los Estados Unidos, en Boston y en Nueva York. -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

Charles Ingersoll: the ^Aristocrat As Copperhead

Charles Ingersoll: The ^Aristocrat as Copperhead HE INGERSOLL FAMILY is one of America's oldest. The first Ingersoll came to America in 1629, just nine years after the T^Mayflower. The first Philadelphia Ingersoll was Jared Inger- soll, who came to the city in 1771 as presiding judge of the King's vice-admiralty court. Previously, he had been the King's colonial agent and stamp master in Connecticut. During the Revolution, Jared remained loyal to the Crown. He stayed in Philadelphia for the first two years of the war, but in 1777, when he and other Tories were forced to leave, he returned to Connecticut, where he lived quietly until his death in 1781.1 Jared's son, Jared, Jr., was the first prominent Philadelphia Inger- soll. He came to Philadelphia with his father in 1771, studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1778. Unlike his father, Jared, Jr., wholeheartedly supported the Revolution. Subsequently, he was a member of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, a member of the city council, city solicitor, attorney general of Pennsylvania, and United States District Attorney. Politically, he was an ardent Fed- eralist, but politics and affairs of state were never his prime interest; his real interest was the law, and most of his time and energy was devoted to his legal practice.2 Jared, Jr.'s, son, Charles Jared Ingersoll, was probably the most interesting of the Philadelphia Ingersolls. Like his father, grand- father, and most of the succeeding generations of Ingersolls, Charles Jared was a lawyer. He began a practice in Philadelphia in 1802, but devoted much of his time to politics. -

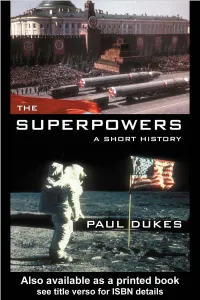

The Superpowers: a Short History

The Superpowers The Superpowers: a short history is a highly original and important book surveying the development of the USA and Russia (in its tsarist, Soviet and post-Soviet phases) from the pre-twentieth century world of imperial powers to the present. It places the Cold War, from inception to ending, into the wider cultural, economic and political context. The Superpowers: a short history traces the intertwining history of the two powers chronologically. In a fascinating and innovative approach, the book adopts the metaphor of a lifespan to explore this evolutionary relationship. Commencing with the inheritance of the two countries up to 1898, the book continues by looking at their conception to 1921, including the effects of the First World War, gestation to 1945 with their period as allies during the Second World War and their youth examining the onset of the Cold War to 1968. The maturity phase explores the Cold War in the context of the Third World to 1991 and finally the book concludes by discussing the legacy the superpowers have left for the twenty- first century. The Superpowers: a short history is the first history of the two major participants of the Cold War and their relationship throughout the twentieth century and before. Paul Dukes is Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Aberdeen. His many books include A History of Russia (Macmillan, 3rd edition, 1997) and World Order in History (Routledge, 1996). To Daniel and Ruth The Superpowers A short history Paul Dukes London and New York First published 2001 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. -

Ten Years of Winter: the Cold Decade and Environmental

TEN YEARS OF WINTER: THE COLD DECADE AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE EARLY 19 TH CENTURY by MICHAEL SEAN MUNGER A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Michael Sean Munger Title: Ten Years of Winter: The Cold Decade and Environmental Consciousness in the Early 19 th Century This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of History by: Matthew Dennis Chair Lindsay Braun Core Member Marsha Weisiger Core Member Mark Carey Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Michael Sean Munger iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Michael Sean Munger Doctor of Philosophy Department of History June 2017 Title: Ten Years of Winter: The Cold Decade and Environmental Consciousness in the Early 19 th Century Two volcanic eruptions in 1809 and 1815 shrouded the earth in sulfur dioxide and triggered a series of weather and climate anomalies manifesting themselves between 1810 and 1819, a period that scientists have termed the “Cold Decade.” People who lived during the Cold Decade appreciated its anomalies through direct experience, and they employed a number of cognitive and analytical tools to try to construct the environmental worlds in which they lived. Environmental consciousness in the early 19 th century commonly operated on two interrelated layers. -

Home Libraries and the Institutionalization of Everyday Practices Among Antebellum New Englanders

Home Libraries and the Institutionalization of Everyday Practices Among Antebellum New Englanders Ronald J. Zboray and Mary Saracino Zboray On 11 January 1845, John Park, a sixty-eight-year-old retired academy teacher, finished reading in his Worcester boardinghouse James Russell Lowell's Conversations on Some of the Old Poets. A recent birthday gift from his neigh• bor, "Colonel" George W. Richardson, the finely bound book was a handsome addition to the 3,000 volumes Park had collected during his long life. Owing to his cramped quarters, he had stored more than 2,000 of these away in a nearby office space he affectionately called "my 'Library.'" As he retired after reading, little did he think that his precious books were in imminent danger or that he would soon be roused with alarm. "At our front door," Park later confided to his diary, "I heard Col Richardson Exclauning *Dr Park's Library is on fire!'"^ Park, Richardson, and a band of local residents raced over to save the li• brary. They found an inferno "like the mouth of an oven, under and behind one of my bookcases—^the contents of which, mostly folios and quartos, were in full blaze." The few buckets of water the group splashed did little to stop the confla• gration, which was "spreading along the wall and behind other bookcases." Fire engines were all too slow in arriving; so, with ahnost superhuman strength driven by desperation, the neighbors moved most of the collection out of harm's way. "[A] number of my fiiends now seized such of my bookcases as were nearest the fire," Park recorded, "and heavy as they were, with an effort which aston• ished me, they took five cases, books and all into Mr. -

Edward Sturgis of Yarmouth, Massachusetts 1613-1695

EDWARD STURGIS OF YARMOUTH, MASSACHUSETTS 1613-1695 AND HIS DESCENDANTS ROGER FAXTON STURGIS, EDITOR PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION AT THE $tanbope preee BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 1914 (PlPase paste in your copy of Book) ADDENDA AND ERRATA. EDWARD STURGIS AND HIS DESCENDANTS. RocrnR FAXTON STURGIS, Editor. p. 22 In thinl line of third paragraph strike out "name m1kn0wn" brackets and substitute "Wendall." p. 22 In reference to Samuel Sturgis (D) strike 011t all after the date 1751 the third paragraph and substitute the following: - ''Fora third wife he marrh•d Abigail Otis a11d had a s011 J (E) born Ot:tuber l':I, 17::i7 aml a daughter l,ncretia CE) l November 11, 1758 (B. '.r. R. 2-275). Administration was grar upon his estate April 25, 1762, he being described as "of llarm:ta gentleman," to .Joseph Otis (his brother-in-law) and to his wi< .Abigail (B. 1'. C. vol. 10, p. 101). His estate was insolve11t am mention is made of children." p. 22 Strike out the reference to Prince Stnrgis (DJ aml sul.JstitutP following paragraph: - " Prince Sturgis (D), the fourth son, married October 12. 1 ElizalJelh Fayerweather and died at Dorchester, Massaeh11se 1779. There was one daughter of this marriage, ElizalJeth lJaptized February 7, 1740 and married December 2fl, liGl, Art Savage. They had five children. The eldest, Faith or Fidt married lkv. Hichard Munkhouse. Tlle others dir,d unmarrirc pp. 22 & 23. Strike out the reference to f-;anrnel (E) beginning at the foo µage 22 and substitute the following: - " Samnel (E), the other so11, married Lydia Crocker, daugl of Cornelius a11d Lydia (.J enkius) Crocker, aml had one child Sn (F) born November 8, 17G0 (4 B. -

1. ABBOT, Gorham D. Mexico, and the United States; Their Mutual

1. ABBOT, Gorham D . Mexico, and the United States; Their Mutual Relations and Common Interests . Illustrated with two steel- engraved portraits and one folding, colored map by Colton of Mexico and much of Texas and the Southwest. 8vo, New York: G. P. Putnam & Son, 1869. First edition. Original green cloth gilt. An impeccable, fresh copy, inscribed by the author on the title page. Bookplate adhering to flyleaf. $1,500 A key early work on the history of U.S.-Mexican relations, with portraits of Juarez and Romero, and a detailed and beautifully colored map of Mexico (17 ½ x 25 ¾ inches). Inscribed on the title page, “J W Hamersley Esq | with the respects of | Gorham D. Abbot.” ’ 2. ANDREWS, Roy Chapman . The New Conquest of Central Asia. A Narrative of the Explorations of the Central Asiatic Expeditions in Mongolia and China, 1921-1930 . The Natural History of Central Asia vol. I, Chester A. Reed, editor. With chapters by Walter Granger … Clifford H. Pope … Nels C. Nelson … with 128 plates and 12 illustrations in the text and 3 maps at end. lx, 678pp. 4to, New York: The American Museum of Natural History, 1932. First edition. Publisher’s orange cloth stamped in black. Minor wear at extremities. Archival repair to pp. 335-6. An attractive and extremely desirable copy. In custom black morocco-backed slipcase with inner wrapper. Yakushi A 223. $4,500 The New Conquest of Central Asia is a lavishly produced volume that stands as one of the landmarks of twentieth-century exploration. This copy is from the library of the author, Roy Chapman Andrews. -

History of the U.S. Attorneys

Bicentennial Celebration of the United States Attorneys 1789 - 1989 "The United States Attorney is the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done. As such, he is in a peculiar and very definite sense the servant of the law, the twofold aim of which is that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer. He may prosecute with earnestness and vigor– indeed, he should do so. But, while he may strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction as it is to use every legitimate means to bring about a just one." QUOTED FROM STATEMENT OF MR. JUSTICE SUTHERLAND, BERGER V. UNITED STATES, 295 U. S. 88 (1935) Note: The information in this document was compiled from historical records maintained by the Offices of the United States Attorneys and by the Department of Justice. Every effort has been made to prepare accurate information. In some instances, this document mentions officials without the “United States Attorney” title, who nevertheless served under federal appointment to enforce the laws of the United States in federal territories prior to statehood and the creation of a federal judicial district. INTRODUCTION In this, the Bicentennial Year of the United States Constitution, the people of America find cause to celebrate the principles formulated at the inception of the nation Alexis de Tocqueville called, “The Great Experiment.” The experiment has worked, and the survival of the Constitution is proof of that. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art VOLUME I THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 1 PAINTERS BORN BEFORE 1850 THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C Copyright © 1966 By The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20006 The Board of Trustees of The Corcoran Gallery of Art George E. Hamilton, Jr., President Robert V. Fleming Charles C. Glover, Jr. Corcoran Thorn, Jr. Katherine Morris Hall Frederick M. Bradley David E. Finley Gordon Gray David Lloyd Kreeger William Wilson Corcoran 69.1 A cknowledgments While the need for a catalogue of the collection has been apparent for some time, the preparation of this publication did not actually begin until June, 1965. Since that time a great many individuals and institutions have assisted in com- pleting the information contained herein. It is impossible to mention each indi- vidual and institution who has contributed to this project. But we take particular pleasure in recording our indebtedness to the staffs of the following institutions for their invaluable assistance: The Frick Art Reference Library, The District of Columbia Public Library, The Library of the National Gallery of Art, The Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress. For assistance with particular research problems, and in compiling biographi- cal information on many of the artists included in this volume, special thanks are due to Mrs. Philip W. Amram, Miss Nancy Berman, Mrs. Christopher Bever, Mrs. Carter Burns, Professor Francis W.