Vol 1 Issue 2 Cole Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pablo Bio-Bibliographical Sketch

Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet Michel Pablo Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: Basic biographical data Biographical sketch Selective bibliography Basic biographical data Name: Michel Pablo Other names (by-names, pseud. etc.): Abdelkrim ; Alain ; Archer ; Gabe ; Gabriel ; Henry ; Jérôme ; J.P. Martin ; Jean-Paul Martin ; Mike; Molitor ; M.P. ; Murat ; Pilar ; Michalēs N. Raptēs ; Michel Raptis ; Mihalis Raptis ; Mikhalis N. Raptis ; Robert ; Smith ; Spero ; Speros ; Vallin Date and place of birth: August 24, 1911, Alexandria (Egypt) Date and place of death: February 17, 1996, Athens (Greece) Nationality: Greek Occupations, careers, etc.: Civil engineer, professional revolutionary Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1928 - 1964 (1995) Biographical sketch A lifelong revolutionary, Michel Pablo for some one and a half decades was the chief leader of the Trotskyist Fourth International – or at least of its majority faction. He was perhaps one of the most renowned and at the same time one of the most controversial figures of the international Trotskyist movement; for all those claiming for themselves the label of "orthodox" Trotskyism, Pablo since 1953 was a whipping boy and the very synonym for centrism, revisionism, opportunism, and even for liquidationism. 'Michel Pablo' is one (and undoubtedly the best known) of more than about a dozen pseudonyms used by a man who was born Michael Raptis [Mikhalēs Raptēs / Μισέλ Πάμπλο]1 as son of Nikolaos Raptis [Raptēs], a Greek civil engineer, in Alexandria (Egypt) on August 24, 1911. He grew up and attended Greek schools in Egypt and from 1918 in Crete before, at the age of 17, he moved to Athens enrolling at the Polytechnic where he studied engineering. -

PDF Print Version

AUSTRALIA $1.50 · CANADA $1.50 · F RANCE 1.00 EURO · NEW ZEALAND $1.50 · UK £.50 · U.S. $1.00 INSIDE Sankara’s revolutionary legacy discussed at NY forum — PAGE 6 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 83/NO. 20 MAY 20, 2019 Latest fighting Uber, Lyft drivers strike Demand US shows need for across US for pay, dignity hands off recognition of Venezuela Israel, Palestine THBY SGAE LINSKY and Cuba! A new tenuous cease-fire agreement BY TERRY EVANS between the Israeli government and “The Socialist Workers Party urg- Gaza-based Hamas and Palestinian es working people and youth to join in speaking out against Washing Islamic Jihad does nothing to elimi- - nate the unending cycle of violence by ton’s threats against Venezuela and groups in the Gaza Strip committed Cuba,” said John Studer, a member to the destruction of Israel and Israel’s of the SWP Political Committee and editor of the Militant, capitalist rulers. The repeated mili - at a special tary battles there are a deadly obstacle Militant Labor Forum here May 4. It to uniting working people, whatever was organized as a call to action to mobilize opposition to the U.S. rul their religion or nationality, to ad- - ers’ intervention. vance their interests against the capi- talist governments and ruling classes Studer urged forum participants to on both sides of the border. initiate and build protests demanding At the heart of the repeated fighting an immediate and unconditional halt to the U.S. government’s violations is the refusal of Hamas, the reaction- Militant/Edwin Fruit ary Islamist group that runs the Gaza Uber, Lyft strikers rally in Seattle May 8. -

Nicolas Maduro Won the Presidential Election

Newsletter of the Hands Off Venezuela campaign www.handsoffvenezuela.org May 2013 Defend Venezuela’s democracy Nicolas Maduro won the presidential election - respect the democratic will of the people n April 14, the Bo- the day after, with the presence livarian candidate of opposition technicians and no Nicolás Maduro complaint was registered won the presiden- • on election night 54% of poll- Otial elections with 7,586,251 ing booths, chosen randomly, votes (50.61%) against the op- were publicly audited with the position candidate Henrique presence of opposition and Bo- Capriles who received 7,361,512 livarian observers. The voting votes (49.12%), with a turnout of results recorded by the voting 79.69%. machines were checked against The opposition refused to rec- the paper receipts in the boxes. ognise the results of the election No complaints were registered. and has launched a campaign of • the elections were observed violence. On the night of April by over 170 international observ- 15 several CDI health clinics ers from many countries includ- were attacked across the coun- ing India, Brazil, Great Britain, try, as well as alternative and Argentina, South Korea, Spain state media outlet buildings and and France. Among the observ- journalists, offices of the United ers were two former presidents Socialist Party of Venezuela, etc. (of Guatemala and the Domini- As a result of this politically mo- can Republic), judges, lawyers tivated violence 9 people were and high-ranking officials of killed, all of them in the Bolivar- national electoral councils. All ian camp. of them stated that the elections The noisy campaign of the had been free and fair and the opposition was combined with system transparent, reliable, The working masses defend the Bolivarian revolution pic: Prensa Presidencial a national and international well-run and thoroughly au- media campaign, international dited. -

Ray O' Light Newsletter

RAY O’ LIGHT NEWSLETTER March-April 2019 No. 113 & May-June 2019 No. 114 DOUBLE ISSUE Publication of the Revolutionary Organization of Labor, USA Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Founding of the Communist International March 1919 REFLECTIONS ON THE COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL ON THE OCCASION OF THE HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY OF ITS FOUNDING (1919-2019) by RAY LIGHT “Departing from us, Comrade Lenin enjoined us to I. remain faithful to the principles of the Communist FROM THE FORMATION OF THE COMINTERN International. We vow to you, comrade Lenin, that we AND THE VICTORY OF THE OCTOBER shall not spare our lives to strengthen and extend the SOCIALIST REVOLUTION IN RUSSIA union of the working people of the whole world—the TO THE COMINTERN’S 7TH CONGRESS Communist International!” — Joseph Stalin, (Stalin, Works, Vol.6, p. 52) One hundred years ago the first world conference of communist parties and social-democratic organizations “... the pressure of the capitalist states on our state is was held in the still newly liberated land of Soviet enormous, ... the people handling our foreign policy do Russia, in the midst of a Civil War and the imperialist not always succeed in resisting this pressure, the danger intervention of a dozen foreign powers. It began with of complications often gives rise to the temptation to take Lenin’s opening speech on March 2, 1919. In the the path of least resistance, the path of nationalism ... course of the next four days a proposal was put forth the path of least resistance and of nationalism in foreign and implemented to transform the conference into a policy is the path of the isolation and decay of the first constitutive congress of the Communist International. -

What Happened to the Workers' Socialist League?

What Happened to the Workers’ Socialist League? By Tony Gard (as amended by Chris Edwards and others), September 1993 Note by Gerry D, October 2019: This is the only version I have of Tony Gard’s docu- ment, which contains the unauthorised amendments as explained in the rather tetchy note by Chris Edwards below. [Note by Chris Edwards (May 2002). War is the sternest possible test for any Trot- skyist organisation. While many British organisations failed this test in the case of the Malvinas/Falklands War (e.g. the Militant group with its “workers war” against Argen- tina position), the British proto-ITO comrades did attempt to defend a principled posi- tion against the bankrupt positions of the leadership of their own organisation, the British Workers Socialist League (WSL). This is an account of the tendency struggle over the Malvinas war and many other is- sues to do with British imperialism. This document was written with the stated purpose of being a “balance sheet” of the tendency struggle. It was somewhat ironic that, Tony G, the author of most of this document, and the person who had played the least part in the WSL tendency struggle during 1982-3, felt himself most qualified to sit in judge- ment on the efforts of those who had been centrally involved in the tendency struggle. This was despite his insistence that he did not wish to do so at the beginning of this ac- count (see below). In fact, one of the barely disguised purposes of this “balance sheet” was to rubbish and belittle the efforts of the comrades who had been centrally involved in the tendency struggle. -

Us Hands Off Venezuela!

AUSTRALIA $1.50 · CANADA $1.50 · FRANCE 1.00 EURO · NEW ZEALAND $1.50 · UK £.50 · U.S. $1.00 INSIDE Kurdish union leader: Workers faced years of tyranny, war — PAGE 6 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE Vol. 83/no. 19 May 13, 2019 NY Workers US hands off Venezuela! Memorial Day: US hands off Cuba! No one needs Washington steps up its war threats, as coup attempt fails to die on the job BY BRIAN WIllIAMS AND JANET POST NEW YORK — “I’m going to fall!” 51-year-old Nelson Salinas yelled as he clung to a scaffold suspended seven sto- ries high against a building in midtown Manhattan April 8. He had been hit in the head by a falling stone pried loose from the top of the building while work was being done to restore it. Salinas was rescued but died in the hospital shortly afterwards. He had worked in construc- tion for 20 years. Salinas’ death and that of two other construction workers here that week, aren’t “accidents,” but the result of the bosses’ relentless drive for profits. Com- panies and contractors have increasing- Reuters/Alexandre Meneghini Hundreds of thousands of people march during May Day rally in Havana to protest U.S. threats. Banner says, “Unity, Commitment and Victory.” ly pushed unions out of more and more sites, pressuring workers to go harder BY SETH GALINSKY Party has issued a call to action, urging and called on army officials to over- and faster. This means rising deaths and In the aftermath of a failed U.S.- working people to organize and join in throw the government. -

To Download As

Solidarity& Workers’ Liberty For social ownership of the banks and industry Reminiscences of Ted Knight, 1933-2020 By Sean Matgamna am saddened by the death of Ted Knight (30 March 2020). I knew him well long ago in the Orthodox Trotskyist organisa- Ition of the late 1950s and early 1960s. When I first encountered him, Ted was a full-time organiser for the Socialist Labour League (SLL), responsible for the Man- chester and Glasgow branches, alternating a week here and a week there. He was on a nominal wage of £8 a week and was lucky if he got £4. He recruited me, then an adolescent member of the Young Communist League, to the SLL. I’d come to think of myself as a Trotskyist, but was unconvinced - didn’t want to be convinced, I suppose - that a revolution was needed to overthrow the Rus- sian bureaucracy. Ted Knight (in middle background) with Bertrand Russell (right Ted lent me his copy of Trotsky’s The Revolution Betrayed. I foreground) and Russell’s secretary Ralph Schoenman (bearded, didn’t take a lot of persuading, as I recall it. left). From The Newsletter, 25 June 1966 That Ted Knight would have been very surprised to find his obituary in the Morning Star headlined “A giant of the labour of the Orthodox Trotskyist Labour Review when it became a big movement” (as if the Morning Star would know about such A4-sized magazine designed for (successful) intervention into things!). the crisis-ridden Communist Party from January 1957. But in The Manchester SLL branch I joined early in 1960 was going 1959-60 there was still a great deal of the old hostility to Trot- through a bad period. -

U.S. Hands Off Venezuela!

"We are realists... we dream the impossible" - Che Fire This Time! CANADA MUST STOP DISCRIMINATING AGAINST INDIGENOUS CHILDREN Page 4 CHE GUEVARA'S LEGACY TODAY Page 24 Page 12 LA LUCHA CONTRA EL NEOLIBERALISMO EN CHILE "SONIC ATTACKS" IN CUBA: FACT OR FICTION?Page 10 U.S. HANDS OFF VENEZUELA! Page 8 STOP THE WAR ON YEMEN Page 18 & 22 Page 2 NO TMX PIPELINE! Page 6 Volume 13 Issue 12 • December 2019 • In English / En Español • Free • $3 at Bookstores www.firethistime.net On November 22, 2019, Stop the UN Yemen envoy Martin Griffiths told the Genocide in UN Security Council that “In the last two weeks, Yemen! the rate of that war has dramatically reduced: U.S. & Saudi there were reportedly Arabia almost 80% fewer airstrikes nation-wide Hands Off than in the two weeks prior.” While the bombing Yemen! and military intervention in Yemen might seem lower, the war on the people of Yemen is still very much in full force. According to the UN, 80% of the population in Yemen needs humanitarian assistance. The bombing destroyed schools, homes, hospitals, By Azza Rojbi water and sanitation systems, roads and against Yemen in March 2015. Throughout countless other vital parts of infrastructure these years the Saudi-led coalition justified its “The war destroyed our dreams and [our] in the country. Added to that, the U.S. and war by renaming its campaign; giving several Saudi-led coalition have been imposing a sea, future” this was how Yemeni mother Adeeyah pretexts for continuing it; and arrogantly described the war in her country in the recently land, and air blockade on Yemen, creating claiming to have the interest of the Yemeni extreme shortages of food, fuel, and medicine. -

Socialist Workers Party Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1k40019v No online items Register of the Socialist Workers Party records Finding aid prepared by Hoover Institution Archives Staff Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6010 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2016 Register of the Socialist Workers 92036 1 Party records Title: Socialist Workers Party records Date (inclusive): 1928-1998 Collection Number: 92036 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 135 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box(57.8 linear feet) Abstract: Correspondence, minutes, resolutions, theses, and internal bulletins, relating to Trotskyist and other socialist activities in Latin America, Western Europe, Iran, and elsewhere, and to interactions of the Socialist Workers Party with the Fourth International; and trial transcripts, briefs, other legal documents, and background materials, relating to the lawsuit brought by Alan Gelfand against the Socialist Workers Party in 1979. Most of collection also available on microfilm (108 reels). Creator: Socialist Workers Party. Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all audiovisual material is immediately accessible. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Socialist Workers Party Records, [Box no.], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information The Hoover Institution Archives acquired records of the Socialist Workers Party from the Anchor Foundation in 1992. -

Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC)

t9 resist « to The mass movement in solidarity with _theVietnamese people againsT imperialism was a major feature of 1968 in Britain. It was the focus for the radicalisation of entire L an generation: a radicalisation which went beyond the single issue of Vietnam and led many thousands to embrace varying forms of revolutionarypolitics. TESSA VAN GELDEREN spoke to PAT JORDAN and TARIQ ALI, both founding members and leading figures in the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC). Pat Jordan was a full time worker for the campaign during the mass demonstrationsof 1967 and 1968. He was a member of the International Marxist Group at the time and has been a lifelong fighter for socialism. Pat is currently recovering from the effects of a stroke. In 1967-68 Tariq Ali’s picture was never far from the front pages of the press. An editorial board member of Black Dwarf, he became a symbol of the mass demonstrations and occupations. His book about the period, Street PAT JORDAN The orientation of CND was to get the Fighting Years: An Autobiographycf Labour Party to adopt unilateralism. the Sixties, is reviewed elsewhere CND WAS THE left campaign of Then Aneurin Bevan, after initially sup- the fifties, its main activity porting unilateralism, made his famous in this issue. was a once—yearly march from Al- somersault. This rapidly disillusioned dermaston. The march was like people. They realised that they needed a revolutionary university — people ar- something else other than this simple guing, tactics and strategy debated, orientationwhich was entirely within the thousands of papers bought and sold. -

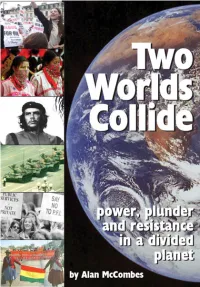

Two Worlds Collide Power, Plunder and Resistance in a Divided Planet

Two Worlds Collide power, plunder and resistance in a divided planet by Alan McCombes CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: THE ROAD TO GLENEAGLES .................................... 5 War, inequality and hypocrisy in the 21st century CHAPTER ONE: THE HIGH PRIESTS OF CAPITALISM ....................... 12 The gang of eight and the global sweatshop economy CHAPTER TWO: FOOTLOOSE AND FREE .......................................... 20 The rise of globalisation and transnational power today CHAPTER THREE: THE TRIANGLE OF GREED ................................. 27 The three shadowy institutions who write the rules CHAPTER FOUR: CAN THE MONSTER BE TAMED? .......................... 33 Can capitalism be reformed, or must it be overthrown? CHAPTER FIVE: LOCAL ACTION AND GLOBAL VISION .................... 42 From Caracas to Chiapas, from Havana to Edinburgh CHAPTER SIX: CLEAR DAY DAWNING ............................................. 51 Breaking the Scottish link in the chain of global capitalism SOURCES ........................................................................................... 61 5 Introduction THE ROAD TO GLENEAGLES NOT SINCE ELVIS Presley’s gyrating hips scandalised respectable society in the 1950s has a pop star provoked such panic. In an edi- torial which only stopped short of proclaiming Apocalypse Now, Scotland on Sunday on 6 June 2005 warned of “beleagured Scottish cities”, a “mushrooming threat”, a “crisis on British soil”. Some people might momentarily have jumped to the conclusion that Osama bin Laden was about to release a deadly cloud of anthrax over Arthur’s Seat. In fact, the evil villain who is terrorising newspaper editors of a nervous disposition is no turbanned terrorist nor mustachioed dictator, but ex-Boomtown Rat and hero of Live Aid, Bob Geldof. His appeal for a million people to march in Edinburgh has been portayed in some quarters as as the war cry of a megalomaniac tyrant, out to ransack our capital city with a horde of savages in tow. -

Ken Kalturnyk and Karen Naylor 4 from the Food Bank to the Luggage Carousel

#15 JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2007 $3.00 R EA SOCIALISTL PROJECTA Y REVIEW ISRAELI APARTHEID, ISRAELI WARS • U.S. ELECTIONS AMERICA SINKING? • CUBA IN THE COMING PERIOD PINOCHET IS GONE • DEMOCRACY IN GREECE About Relay Relay, A Socialist Project Review, intends to act as a forum for conveying and debating current issues of importance to the Left in Ontario, Editor: Canada and from around the world. Contributions to the re-laying of the foun- Peter Graham dations for a viable socialist politics are welcomed by the editorial committee. Culture Editor: Tanner Mirrlees Relay is published by the Socialist Project. Signed articles reflect the opinions Web Editor: of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the editors. Pance Stojkovski Advisory Board: About the Socialist Project Greg Albo Len Bush The Socialist Project does not propose an easy politics for defeating capitalism Yen Chu or claim a ready alternative to take its place. We oppose capitalism out of Carole Conde necessity and support the resistance of others out of solidarity. This resistance Bryan Evans creates spaces of hope, and an activist hope is the first step to discovering a Richard Fidler new socialist politics. Through the struggles of that politics – struggles informed Matt Fodor by collective analysis and reflection – alternatives to capitalism will emerge. Jess MacKenzie Such anti-capitalist struggles, we believe, must develop a viable working class nchamah miller politics, and be informed by democratic struggles against racial, sexist and Govind Rao homophobic oppressions, and in support of the national self-determination of Richard Roman the many peoples of the world.