The Rama Story of Brij Narain Chakbast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antiquities of Madhava Worship in Odisha

August - 2015 Odisha Review Antiquities of Madhava Worship in Odisha Amaresh Jena Odisha is a confluence of innumerable of the Brihadaranayaka sruti 6 of the Satapatha religious sects like Buddhism, Jainism, Saivism, Brahman belonging to Sukla Yajurveda and Saktism, Vaishnavism etc. But the religious life of Kanva Sakha. It is noted that the God is realized the people of Odisha has been conspicuously in the lesson of Madhu for which he is named as dominated by the cult of Vaishnavism since 4th Madhava7. Another name of Madhava is said to Century A.D under the royal patronage of the have derived from the meaning Ma or knowledge rulling dynasties from time to time. Lord Vishnu, (vidya) and Dhava (meaning Prabhu). The Utkal the protective God in the Hindu conception has Khanda of Skanda Purana8 refers to the one thousand significant names 1 of praise of which prevalence of Madhava worship in a temple at twenty four are considered to be the most Neelachala. Madhava Upasana became more important. The list of twenty four forms of Vishnu popular by great poet Jayadev. The widely is given in the Patalakhanda of Padma- celebrated Madhava become the God of his love Purana2. The Rupamandana furnishes the and admiration. Through his enchanting verses he twenty four names of Vishnu 3. The Bhagabata made the cult of Radha-Madhava more familiar also prescribes the twenty four names of Vishnu in Prachi valley and also in Odisha. In fact he (Keshava, Narayan, Madhava, Govinda, Vishnu, conceived Madhava in form of Krishna and Madhusudan, Trivikram, Vamana, Sridhara, Radha as his love alliance. -

Kashmir Conflict: a Critical Analysis

Society & Change Vol. VI, No. 3, July-September 2012 ISSN :1997-1052 (Print), 227-202X (Online) Kashmir Conflict: A Critical Analysis Saifuddin Ahmed1 Anurug Chakma2 Abstract The conflict between India and Pakistan over Kashmir which is considered as the major obstacle in promoting regional integration as well as in bringing peace in South Asia is one of the most intractable and long-standing conflicts in the world. The conflict originated in 1947 along with the emergence of India and Pakistan as two separate independent states based on the ‘Two-Nations’ theory. Scholarly literature has found out many factors that have contributed to cause and escalate the conflict and also to make protracted in nature. Five armed conflicts have taken place over the Kashmir. The implications of this protracted conflict are very far-reaching. Thousands of peoples have become uprooted; more than 60,000 people have died; thousands of women have lost their beloved husbands; nuclear arms race has geared up; insecurity has increased; in spite of huge destruction and war like situation the possibility of negotiation and compromise is still absence . This paper is an attempt to analyze the causes and consequences of Kashmir conflict as well as its security implications in South Asia. Introduction Jahangir writes: “Kashmir is a garden of eternal spring, a delightful flower-bed and a heart-expanding heritage for dervishes. Its pleasant meads and enchanting cascades are beyond all description. There are running streams and fountains beyond count. Wherever the eye -

"Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland

"Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland Author(s): Haley Duschinski Source: International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Apr., 2008), pp. 41-64 Published by: Springer Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40343840 Accessed: 12-01-2020 07:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of Hindu Studies This content downloaded from 134.114.107.39 on Sun, 12 Jan 2020 07:34:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland Haley Duschinski Kashmiri Hindus are a numerically small yet historically privileged cultural and religious community in the Muslim- majority region of Kashmir Valley in Jammu and Kashmir State in India. They all belong to the same caste of Sarasvat Brahmanas known as Pandits. In 1989-90, the majority of Kashmiri Hindus living in Kashmir Valley fled their homes at the onset of conflict in the region, resettling in towns and cities throughout India while awaiting an opportunity to return to their homeland. -

The Mysterious Controller of the Universe : Shri Neelamadhava - Shri Jagannath

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review Madhava Madhava vacyam, Madhava madhava harih; Smaranti Madhava nityam, sarva karye su Madhavah. Towards the end of Lord Sri Rama’s regime in Tretaya Yuga, Sri Hanuman was advised by the Lord Sri Rama to remain immersed in meditation (dhyanayoga) in ‘Padmadri hill’ till his services would be recalled in Dwapar Yuga. When the great devotee, Sri Hanuman expressed his prayer as to how he would see his divine Master during such a long spell of time, the Lord advised him that he would be able to see his ever- The Mysterious Controller of the Universe : Shri Neelamadhava - Shri Jagannath Dr. K.C. Sarangi Lord, always desires His devotees to have cherished ‘Sri Rama’ in the form of Lord Sri equanimity in all circumstances: favourable or Neelamadhava whom he would worship in unfavourable, and to destroy their ingorance by ‘Brahmadri’, the adjacent hill and enjoy the the sword of conscience, ‘tasmat ajnana everlasting bliss ‘naisthikeem shantim’ as the sambhutam hrutstham jnanasinatmanah (Ch. IV, Gita describes (Ch.5, Verse 12). Sri Hanuman verse.42) and work in a detached manner was a sthitadhi. Those devotees, whose minds surrendering the fruit of all actions to the Lotus are equiposed, attend the victory over the world feet of the Lord so that the devotee does not during their life time. Since Paramatma the become partaker of the sins as the Lotus leaf is Almighty Father is flawless and equiposed, such not affected by water ‘brahmani adhyaya devotees rest in the lotus feet of the Lord karmani sangam tyaktwa karoiti yah, lipyate ‘nirdosam hi samam brahma tasmad na sa papena padmapatramivambasa’ (Ch.V, brahmani te sthitaah’, (ibid v.19). -

Multidimensional Role of Women in Shaping the Great Epic Ramayana

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.academicsjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 6; November 2017; Page No. 1035-1036 Multidimensional role of women in shaping the great epic Ramayana Punit Sharma Assistant Professor, Institute of Management & Research IMR Campus, NH6, Jalgaon, Maharashtra, India Abstract We look for role models all around, but the truth is that some of the greatest women that we know of come from Indian mythology Ramayana. It is filled with women who had the fortitude and determination to stand up against all odds ones who set a great example for generations to come. Ramayana is full of women, who were mentally way stronger than the glorified heroes of this great Indian epic. From Jhansi Ki Rani to Irom Sharmila, From Savitribai Fule to Sonia Gandhi and From Jijabai to Seeta, Indian women have always stood up for their rights and fought their battles despite restrictions and limitations. They are the shining beacons of hope and have displayed exemplary dedication in their respective fields. I have studied few characters of Ramayana who teaches us the importance of commitment, ethical values, principles of life, dedication & devotion in relationship and most importantly making us believe in women power. Keywords: ramayana, seeta, Indian mythological epic, manthara, kaikeyi, urmila, women power, philosophical life, mandodari, rama, ravana, shabari, surpanakha Introduction Scope for Further Research The great epic written by Valmiki is one epic, which has Definitely there is a vast scope over the study for modern day mentioned those things about women that make them great. -

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava Sampradaya Connected to the Madhva Line?

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? – Jagadananda Das – The relationship of the Madhva-sampradaya to the Gaudiya Vaishnavas is one that has been sensitive for more than 200 years. Not only did it rear its head in the time of Baladeva Vidyabhushan, when the legitimacy of the Gaudiyas was challenged in Jaipur, but repeatedly since then. Bhaktivinoda Thakur wrote in his 1892 work Mahaprabhura siksha that those who reject this connection are “the greatest enemies of Sri Krishna Chaitanya’s family of followers.” In subsequent years, nearly every scholar of Bengal Vaishnavism has cast his doubts on this connection including S. K. De, Surendranath Dasgupta, Sundarananda Vidyavinoda, Friedhelm Hardy and others. The degree to which these various authors reject this connection is different. According to Gaudiya tradition, Madhavendra Puri appeared in the 14th century. He was a guru of the Brahma or Madhva-sampradaya, one of the four (Brahma, Sri, Rudra and Sanaka) legitimate Vaishnava lineages of the Kali Yuga. Madhavendra’s disciple Isvara Puri took Sri Krishna Chaitanya as his disciple. The followers of Sri Chaitanya are thus members of the Madhva line. The authoritative sources for this identification with the Madhva lineage are principally four: Kavi Karnapura’s Gaura-ganoddesa-dipika (1576), the writings of Gopala Guru Goswami from around the same time, Baladeva’s Prameya-ratnavali from the late 18th century, and anothe late 18th century work, Narahari’s -

Kaveri – 2019 Annual Day Script Bala Kanda: Rama

Kaveri – 2019 Annual Day Script Bala Kanda: Rama marries Sita by breaking the bow of Shiva Janaka: I welcome you all to Mithila! As you see in front of you, is the bow of Shiva. Whoever is able to break this bow of Shiva shall wed my daughter Sita. Prince 1: Bows to the crowd and tries to lift the bow and is unsuccessful Prince 2: Bows to the crowd and tries to lift the bow and is unsuccessful Rama 1: Bows, prays to the bow, lifts it, strings it and pulls the string back and bends and breaks it Janaka: By breaking Shiva’s bow, Rama has won the challenge and Sita will be married to Rama the prince of Ayodhya. Ayodhya Kanda: Narrator: Rama, Sita, Lakshmana, Shatrugna, Bharata are all married in Mithila and return to Ayodhya and lived happily for a number of years. Ayodhya rejoiced and flourished under King Dasaratha and the good natured sons of the King. King Dasaratha felt it was time to crown Rama as the future King of Ayodhya. Dasaratha: Rama my dear son, I have decided that you will now become the Yuvaraja of Ayodhya and I would like to advice you on how to rule the kingdom. Rama 2: I will do what you wish O father! Let me get your blessings and mother Kausalya’s blessings. (Rama bows to Dasaratha and goes to Kausalya) Kausalya: Rama, I bless you to rule this kingdom just like your father. Narrator: In the mean time, Manthara, Kaikeyi’s maid hatches out an evil plan. -

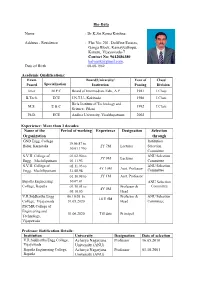

Dr.K.Sri Rama Krishna Address

Bio-Data Name : Dr.K.Sri Rama Krishna Address - Residence : Flat No: 201, Dolffine Estates, Ganga Block, Kamayyathopu, Kanuru, Vijayawada-7 Contact No: 9642086380 [email protected], Date of Birth : 08-08-1962 Academic Qualifications: Exam Board/University/ Year of Class/ Passed Specialization Institution Passing Division Inter M.P.C Board of Intermediate Edn., A.P. 1981 I Class B.Tech. ECE J.N.T.U., Kakinada 1986 I Class Birla Institute of.Technology and M.S. E & C 1992 I Class Science., Pilani Ph.D. ECE Andhra University, Visakhapatnam 2002 Experience: More than 3 decades Name of the Period of working Experience Designation Selection Organization through GND Engg. College Institution 19.06.87 to Bidar, Karnataka 2Y 7M Lecturer Selection 30.01.1990 Committee S.V.H. College of 01.02.90 to ANU Selection 3Y 9M Lecturer Engg. Machilipatnam 01.11.93 Committee S.V.H. College of 02.11.93 to ANU Selection 4Y 10M Asst. Professor Engg. Machilipatnam 31.08.98 Committee 01.10.98 to 3Y 1M Asst. Professor Bapatla Engineering 30.09.01 ANU Selection College, Bapatla 01.10.01 to Professor & Committee 4Y 0M 05.10.05 Head V.R.Siddhartha Engg 06.10.05 to Professor & ANU Selection 14 Y 8M College, Vijayawada 31.05.2020 Head Committee PSCMR College of Engineering and 01.06.2020 Till date Principal Technology, Vijayawada Professor Ratification Details: Institution University Designation Date of selection V.R.Siddhartha Engg College, Acharya Nagarjuna Professor 16.05.2010 Vijayawada University (ANU) Bapatla Engineering College, Acharya Nagarjuna Professor 01.10.2001 -

An Overview of the Problems Faced by the Migrant Kashmiri Pandits in Jammu District and Possible Solutions

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN(E): 2321-8878; ISSN(P): 2347-4564 Vol. 2, Issue 9, Sep 2014, 71-86 © Impact Journals AN OVERVIEW OF THE PROBLEMS FACED BY THE MIGRANT KASHMIRI PANDITS IN JAMMU DISTRICT AND POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS SOM RAJ 1, SUNITA SHARMA 2 & VARINDER SINGH WARIS 3 1,3 Research Scholar, Department of Economics, University of Jammu, Jammu & Kashmir, India 2Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, University of Jammu, Jammu & Kashmir, India ABSTRACT Migration is generally a movement of people from their origin of place to another place for the purpose of setting down permanent or temporary and the nature of migration is broadly classified in terms of type of choice (voluntary or involuntary) or geographical territory (international or internal), rural to rural, rural to urban, urban to urban etc. The involuntary or voluntary forced migration is caused due to a variety of reasons. However, the state of J&K has experienced the various types of migration due to number of reasons like growth of militancy especially in Kashmir valley and its adjoining areas since the year 1988. The early 1990’s period, witnessed killing of many people supporting Indian rule espically Kashmiri Pandits, in Kashmir valley. The government had failed to control militancy conflicts and to provide security to minority of kashmiri Pandits and under these bad circumstances kashmiri Pandits started migration and left their native Kashmir valley. Now these Pandits have settled in various parts of the country. This paper tries to find out the problems faced by the migrant Kashmiri Pandits, settled in Camp as well as Non-Camp areas of Jammu District. -

Ramanuja Darshanam

Table of Contents Ramanuja Darshanam Editor: Editorial 1 Sri Sridhar Srinivasan Who is the quintessential SriVaishnava Sri Kuresha - The embodiment of all 3 Associate Editor: RAMANUJA DARSHANAM Sri Vaishnava virtues Smt Harini Raghavan Kulashekhara Azhvar & 8 (Philosophy of Ramanuja) Perumal Thirumozhi Anubhavam Advisory Board: Great Saints and Teachers 18 Sri Mukundan Pattangi Sri Stavam of KooratazhvAn 24 Sri TA Varadhan Divine Places – Thirumal irum Solai 26 Sri TCA Venkatesan Gadya Trayam of Swami Ramanuja 30 Subscription: Moral story 34 Each Issue: $5 Website in focus 36 Annual: $20 Answers to Last Quiz 36 Calendar (Jan – Mar 04) 37 Email [email protected] About the Cover image The cover of this issue presents the image of Swami Ramanuja, as seen in the temple of Lord Srinivasa at Thirumala (Thirupathi). This image is very unique. Here, one can see Ramanuja with the gnyAna mudra (the sign of a teacher; see his right/left hands); usually, Swami Ramanuja’s images always present him in the anjali mudra (offering worship, both hands together in obeisance). Our elders say that Swami Ramanuja’s image at Thirumala shows the gnyAna mudra, because it is here that Swami Ramanuja gave his lectures on Vedarta Sangraha, his insightful, profound treatise on the meaning of the Upanishads. It is also said that Swami Ramanuja here is considered an Acharya to Lord Srinivasa Himself, and that is why the hundi is located right in front of swami Ramanuja at the temple (as a mark of respect to an Acharya). In Thirumala, other than Lord Srinivasa, Varaha, Narasimha and A VEDICS JOURNAL Varadaraja, the only other accepted shrine is that of Swami Ramanuja. -

Is Jesus a Hindu? S.C

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 13 Article 8 January 2000 Is Jesus a Hindu? S.C. Vasu and Multiple Madhva Misrepresentations Deepak Sarma Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sarma, Deepak (2000) "Is Jesus a Hindu? S.C. Vasu and Multiple Madhva Misrepresentations," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 13, Article 8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1228 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Sarma: Is Jesus a Hindu? S.C. Vasu and Multiple Madhva Misrepresentations Is Jesus a Hindu? S. C. Vasu and Multiple Madhva Misrepresentations Deepak Sarma University of Chicago 1. Introductory Remarks 2. Madhva Vedanta in a Nutshell Misperceptions and misrepresentations are Many readers will be familiar with frequently linked to complicated dynamics Madhvacarya's position. However, for those between those who are misperceived and readers who are suffering from ajnana, those who do the misperceiving. Oftentimes ignorance (or even mumuksu!), I offer a such dynamics are manifestations of under brief introduction to Madhva theology. This lying social, political, or, in the cases synopsis is not to be considered exhaustive. described in this issue of the Hindu For the purposes of this limited discussion I Christian Studies Bulletin, religious appeal to several texts from the Madhva differences. -

The Ramayana by R.K. Narayan

Table of Contents About the Author Title Page Copyright Page Introduction Dedication Chapter 1 - RAMA’S INITIATION Chapter 2 - THE WEDDING Chapter 3 - TWO PROMISES REVIVED Chapter 4 - ENCOUNTERS IN EXILE Chapter 5 - THE GRAND TORMENTOR Chapter 6 - VALI Chapter 7 - WHEN THE RAINS CEASE Chapter 8 - MEMENTO FROM RAMA Chapter 9 - RAVANA IN COUNCIL Chapter 10 - ACROSS THE OCEAN Chapter 11 - THE SIEGE OF LANKA Chapter 12 - RAMA AND RAVANA IN BATTLE Chapter 13 - INTERLUDE Chapter 14 - THE CORONATION Epilogue Glossary THE RAMAYANA R. K. NARAYAN was born on October 10, 1906, in Madras, South India, and educated there and at Maharaja’s College in Mysore. His first novel, Swami and Friends (1935), and its successor, The Bachelor of Arts (1937), are both set in the fictional territory of Malgudi, of which John Updike wrote, “Few writers since Dickens can match the effect of colorful teeming that Narayan’s fictional city of Malgudi conveys; its population is as sharply chiseled as a temple frieze, and as endless, with always, one feels, more characters round the corner.” Narayan wrote many more novels set in Malgudi, including The English Teacher (1945), The Financial Expert (1952), and The Guide (1958), which won him the Sahitya Akademi (India’s National Academy of Letters) Award, his country’s highest honor. His collections of short fiction include A Horse and Two Goats, Malgudi Days, and Under the Banyan Tree. Graham Greene, Narayan’s friend and literary champion, said, “He has offered me a second home. Without him I could never have known what it is like to be Indian.” Narayan’s fiction earned him comparisons to the work of writers including Anton Chekhov, William Faulkner, O.