9 Edinburgh Castle in the Modern Era: Presenting Meanings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

List of Scottish Museums and Libraries with Strong Victorian Collections

Scottish museums and libraries with strong Victorian collections National Institutions National Library of Scotland National Gallery of Scotland National Museums Scotland National War Museum of Scotland National Museum of Costume Scottish Poetry Library Central Libraries The Mitchell Library, Glasgow Edinburgh Central Library Aberdeen Central Library Carnegie Library, Ayr Dick Institute, Kilmarnock Central Library, Dundee Paisley Central Library Ewart Library, Dumfries Inverness Library University Libraries Glasgow University Library University of Strathclyde Library Edinburgh University Library Sir Duncan Rice Library, Aberdeen University of Dundee Library University of St Andrews Library Municipal Art Galleries and Museums Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Glasgow Burrell Collection, Glasgow Aberdeen Art Gallery McManus Galleries, Dundee Perth Museum and Art Gallery Paisley Museum & Art Galleries Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum Stewartry Museum, Kirkcudbright V & A Dundee Shetland Museum Clydebank Museum Mclean Museum and Art Gallery, Greenock Hunterian Art Gallery & Museum Piers Art Centre, Orkney City Art Centre, Edinburgh Campbeltown Heritage Centre Montrose Museum Inverness Museum and Art Gallery Kirkcaldy Galleries Literary Institutions Moat Brae: National Centre for Children’s Literature Writers’ Museum, Edinburgh J. M. Barrie Birthplace Museum Industrial Heritage Summerlee: Museum of Scottish Industrial Life, North Lanarkshire Riverside Museum, Glasgow Scottish Maritime Museum Prestongrange Industrial Heritage Museum, Prestonpans Scottish -

Studiereizen 2018

Studiereizen september 2017 toekomstige leerlingen HAVO5 / VWO5 15 februari 2018 Welkom • Idee achter de studiereizen • Keuze van de bestemmingen • Overige informatie Idee achter de studiereizen • Groepsvorming • Educatief • Keuzemogelijkheid: Praag, Florence, Londen, Berlijn, Barcelona, Edinburgh, Krakau • Excursies Inschrijven • Leerlingen maken een 1e, 2e en 3e keus Vanaf donderdag 22 februari (19.00 uur) – 5 maart (19.00 uur) enquête via de mail • In de derde week van maart wordt via de mail de definitieve indeling aan de leerling medegedeeld. • Leerlingen leveren tussen 15 en 24 maart het bevestigingsformulier (ondertekend door de ouder/verzorger) in bij de mediatheek (in enveloppe met kopie paspoort/ID-kaart en zorgpas) => formulier staat op de ELO Kosten Indicatie/richtlijn kosten: • Barcelona € 475,00 • Berlijn € 350,00 • Edinburgh € 450, 00 • Florence € 500,00 • Praag € 350,00 • Krakau € 400,00 • Londen € 350,00 Te betalen in maximaal twee termijnen (per factuur) voor 1 mei 2018 de eerste termijn (of het gehele bedrag), voor 1 juni 2018 de tweede termijn Overige informatie • Data: 3 september t/m 7 september • Zittenblijven • Inbegrepen en niet inbegrepen Vragen? [email protected] Beelden van Londen Verblijf • The 23 Hostel (voorheen Gallery Hyde Park) • Meerpersoonskamers met douche 1 Hostel Winkelen: 2 London Eye Oxford Street 3 National Gallery Regent Street 4 Natural History Museum Borough Market Globaal programma • London Eye Stadswandeling Westminster abbey Big Ben Buckingham palace Tower Bridge St Pauls Cathedral -

ASVA Visitor Trend Report, August 2019 August 2019 Dashboard

ASVA Visitor Trend Report, August 2019 Dashboard Summary Usable data was received from 200 sites. The total number of visits recorded in August 2019 August 2019 was 3,637,863; this compares to 3,704,347 in 2018 and indicates a decrease of -1.8%. Excluding Country Parks ASVA's Commentary and Observations for August 2019 August 19 3,637,863 -1.8% q Year-to-Date 18,776,619 -2.2% q It is slightly disappointing to report a fall in visitor numbers to ASVA member sites in August, with an overall decrease in visitor numbers of 1.8% (excluding country parks), when compared with figures from the same month in 2018. This Including Country Parks August decrease has a knock on effect on the year to date figures, with the overall year date numbers down 2.2% on August 19 4,071,964 -0.2% q 2018 levels. Looking at data from across the tourism industry, it would appear that Brexit uncertainty is having an Year-to-Date 22,726,379 -4.0% q impact on those travelling from Europe to the UK, with trips from major EU countries such as Germany and France considerably down, and some Scottish attractions, particularly those with high numbers of international visitors, are Per Region feeling this impact. It is however worth noting that there are some considerable differences regionally, with the West region bucking the Northern Scotland 582,974 0.9% p trend and reporting an increase of 6.3%, while South (down 0.1%), North (down 1.8%) and particularly East (down *Northern Scotland † 492,607 -1.8% q This report was 6.2%) all saw decreases. -

The Whistler's Story Tragedy and the Enlightenment Imagination in the Eh Art of Midlothian Alan Riach

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 24 2004 The Whistler's Story Tragedy and the Enlightenment Imagination in The eH art of Midlothian Alan Riach Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Riach, Alan (2004) "The Whistler's Story Tragedy and the Enlightenment Imagination in The eH art of Midlothian," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 33: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol33/iss1/24 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alan Riach The Whistler's Story Tragedy and the Enlightenment Imagination in The Heart ofMidlothian The Heart of Midlothian is generally considered Scott's most approach able novel. David Daiches tells us that "most critics consider [it to be] the best of Scott's works."J In his short but influential 1965 study, it is the only novel to which Thomas Crawford devotes an entire chapter, and in his 1982 revision of the same book, Crawford preserves the emphasis, citing the "extended criti cal debate" to which the novel has been subjected by Robin Mayhead, Dorothy van Ghent, Joan Pittock and David Craig.2 In Scottish Literature since 1707, Marshall Walker tellingly chooses The Heart ofMidlothian above any other of Scott's works for extended consideration before addressing the question of Scott's fluctuating appeal as a novelist, "then and now.,,3 When Ludovic Ken nedy inquired in 1969, he found that the Edinburgh City Library's nine copies of the work were all out. -

To Download Your PDF Copy

TROON OLD PARISH TALK THE MAGAZINE OF TROON OLD PARISH CHURCH Minister: Rev David Prentice-Hyers B.A., M.Div. TEL: 01292 313644 01292 313520 (Office) www.TROONOLD.ORG.UK No. 106 Spring 2019 Foxes Have Holes and Guides have boxes but... The sun was long set and any notion of a dry and clear night was long dispelled when the Guides began to arrive at the Scout Hall. Some prepped a fire in the pit. Others handed out emergency bags which are no more than extra thick oversized bin bags. Still others packed and repacked their sleeping bags. By the time I arrived pea-sized drops were bouncing off the tarmac. It would be a long night before the clouds emptied their tears. The air froze and the winter sun made its cold appearance. These future leaders, doctors, politicians and mothers gave up Netflix and Facebook for one soggy, cold night called the Wee Sleep. They raised no small sum to help eradicate homelessness in Scotland. For these young adventurers what a radical act of empathy: such a wonderful experience in active compassion to sleep a night in another's pain. What is it that Burns says? "O wad some Pow'r the giftie gie us To see oursels as ithers see us!" The Troon Guides Wee Sleep was an affirmative act of selflessness and self-awareness. What a gift to step outside one's awareness, not to see one's folly or vanity, but to feel deeply the brokenness into which too many are forced. What a valuable lesson these young leaders are giving us. -

Review 05 Opening up Our Collections 02 National Museums of Scotland

REVIEW 05 OPENING UP OUR COLLECTIONS 02 NATIONAL MUSEUMS OF SCOTLAND NMS is Scotland’s national NMS holds a wealth of treasures museum service. We care collected over more than two for museum collections of centuries. Our collections national and international encompass Scottish and importance, and present international archaeology, these to the public at our decorative and applied arts, six museums: world cultures, social history, science, technology and the ● Royal Museum and Museum natural world. We also provide of Scotland, Edinburgh advice, expertise and support ● National War Museum of to the museums community Scotland, Edinburgh Castle across Scotland and undertake ● Museum of Flight, East Lothian fieldwork, research and ● Museum of Scottish Country partnerships at local, national Life, near East Kilbride and international levels. ● Shambellie House Museum of Costume, near Dumfries NMS preserves, interprets, and makes accessible for all, the We also have a major Collections past and present of Scotland, Centre at Granton, Edinburgh, of other nations and cultures, which is a focal point for and of the natural world. collections storage and conservation. 1. 2. 3. Scenes from our six museums: 1. Royal Museum 2. Museum of Scotland 3. National War Museum of Scotland 4. Museum of Flight 5. Shambellie House Museum of Costume 6. Museum of Scottish Country Life 4. 5. 6. NMS A world class museums service that informs, educates and inspires. A SUPERSONIC YEAR Over the past few years we have Museum of Flight. Securing one made significant progress in of the seven decommissioned changing our focus to place Concorde aircraft, against visitors and other users at the international competition, was heart of everything we do. -

Edinburgh Castle (Portcullis Gate, Argyle Tower & Lang Stairs) Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC222 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90130) Listed Building (Lang Stairs: LB48221 – Category B) (Portcullis Gate and Argyle Tower: LB48227 – Category A) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last Reviewed: 2019 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE EDINBURGH CASTLE – PORTCULLIS GATE, ARGYLE TOWER AND LANG STAIRS We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: -

Edinburgh's Urban Enlightenment and George IV

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Edinburgh’s Urban Enlightenment and George IV: Staging North Britain, 1752-1822 Student Dissertation How to cite: Pirrie, Robert (2019). Edinburgh’s Urban Enlightenment and George IV: Staging North Britain, 1752-1822. Student dissertation for The Open University module A826 MA History part 2. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2019 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Redacted Version of Record Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Edinburgh’s Urban Enlightenment and George IV: Staging North Britain, 1752-1822 Robert Pirrie LL.B (Hons) (Glasgow University) A dissertation submitted to The Open University for the degree of MA in History January 2019 WORD COUNT: 15,993 Robert Pirrie– A826 – Dissertation Abstract From 1752 until the visit of George IV in 1822, Edinburgh expanded and improved through planned urban development on classical principles. Historians have broadly endorsed accounts of the public spectacles and official functions of the king’s sojourn in the city as ersatz Highland pageantry projecting a national identity devoid of the Scottish Lowlands. This study asks if evidence supports an alternative interpretation locating the proceedings as epochal royal patronage within urban cultural history. Three largely discrete fields of historiography are examined: Peter Borsay’s seminal study of English provincial towns, 1660-1770; Edinburgh’s urban history, 1752-1822; and George IV’s 1822 visit. -

Spring 2010 No.27

Spring 2010 No.27 ATHE MAGAZINE OF THHE ARCHITECTURAL HESRITAGE SOCIETYS OF SCOTLAND For the Study and Protection of Scottish Architecture 2 introduction AHSS contents Magazine Spring 2010 (No. 27) Obituary Collation: Mary Pitt and 03 Carmen Moran Reviews Editor: Mark Cousins 07 News from the Glasite Meeting House Design: Pinpoint Scotland Ltd. 08 News President: The Dowager Countess of 11 Heritage Lottery Fund Wemyss and March Chairman: Peter Drummond 13 Projects Volunteer Editorial Assistants: Walking in the Air Anne Brockington Chris Judson 15 RCAHMS Philip Graham The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland NATIONAL OFFICE Edited by Veronica Fraser. The Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland HS Listing The Glasite Meeting House 20 33 Barony Street Edinburgh 21 Other Organisations EH3 6NX 30 Talking Point Tel: 0131 557 0019 Contemporary architecture in the historic environment. Fax: 0131 557 0049 Email: [email protected] My Favourite Building www.ahss.org.uk 33 Investigation The Rural Church Copyright © AHSS and contributors, 2010 The opinions expressed by contributors in this 36 Consultations publication are not necessarily those of the AHSS. Edited highlights of AHSS responses to recent consultations. The Society apologises for any errors or inadvertent infringements of copyright. 38 Reviews The AHSS gratefully acknowledges assistance from the Royal Commission on the Ancient and 43 Education Historical Monuments of Scotland towards the production costs of the AHSS Magazine. 50 National activities 50 Group activities 54 Group casework 59 Membership 60 Diary CALL FOR CONTRIBUTIONS If you would like to contribute to future issues of AHSS magazine, please contact the editor at [email protected] Submission deadline for the Autumn 2010 issue is 24 July 2010 . -

8. La New Town De James Craig

8. La New Town de James Craig. 8.1. La expansión hacia la New Town. 8.1.1. Contexto histórico de la expansión hacia la New Town. Para el siglo XVIII, los problemas de sobrepoblación de Edimburgo ya eran insufribles. Caminar por la Royal Mile debía generar una sensación realmente aplastante entre edificios que alcanzaban incluso los catorce pisos de altura. Su sociedad, a pesar de haber alcanzado un elevado nivel de desarrollo y complejidad, vivía confinada en un espacio muy reducido, de manera que todas las clases sociales convivían en los mismos edificios conforme a una estratificación vertical. Esta densificación, a falta de infraestructuras de saneamiento, hacía de Edimburgo un lugar insalubre donde sus ciudadanos vivían bajo la amenaza constante de plagas y enfermedades. Por si fuera poco, el mal estado general de los edificios tenía ya a la población acostumbrada a continuos incendios y colapsos. Tras el desarrollo urbanístico hacia el sur en la primera mitad del siglo XVIII, Edimburgo alcanzó su límite del hacinamiento en el interior de sus murallas. Esta situación de decadencia no se correspondía con el momento económico e intelectual que vivía la ciudad, una de las grandes capitales europeas de la Ilustración, donde destacaron figuras de primer nivel como el economista Adam Smith, el filósofo David Hume, el arquitecto Robert Adam, etc. Esta generación de grandes pensadores marcaría el segundo gran hito urbanístico de Edimburgo tras la fundación de la Abadía de Holyrood, extendiendo sus límites hacia el norte buscando el puerto de Leith. Aunque la urbanización de la New Town en un inicio pudiera ser entendida como una Fig 8.1: Plano de Edimburgo en 1742, por William Edgar. -

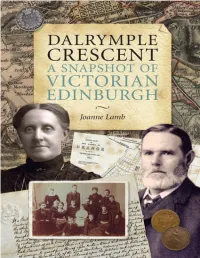

Dalrymple Crescent a Snapshot of Victorian Edinburgh

DALRYMPLE CRESCENT A SNAPSHOT OF VICTORIAN EDINBURGH Joanne Lamb ABOUT THE BOOK A cross-section of life in Edinburgh in the 19th century: This book focuses on a street - Dalrymple Crescent - during that fascinating time. Built in the middle of the 19th century, in this one street came to live eminent men in the field of medicine, science and academia, prosperous merchants and lawyers, The Church, which played such a dominant role in lives of the Victorians, was also well represented. Here were large families and single bachelors, marriages, births and deaths, and tragedies - including murder and bankruptcy. Some residents were drawn to the capital by its booming prosperity from all parts of Scotland, while others reflected the Scottish Diaspora. This book tells the story of the building of the Crescent, and of the people who lived there; and puts it in the context of Edinburgh in the latter half of the 19th century COPYRIGHT First published in 2011 by T & J LAMB, 9 Dalrymple Crescent, Edinburgh EH9 2NU www.dcedin.co.uk This digital edition published in 2020 Text copyright © Joanne Lamb 2011 Foreword copyright © Lord Cullen 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-9566713-0-1 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Designed and typeset by Mark Blackadder The publisher acknowledges a grant from THE GRANGE ASSOCIATION towards the publication of this book THIS DIGITAL EDITION Ten years ago I was completing the printed version of this book.