Edinburgh's Urban Enlightenment and George IV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Custom to Code. a Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football

From Custom to Code From Custom to Code A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football Dominik Döllinger Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Humanistiska teatern, Engelska parken, Uppsala, Tuesday, 7 September 2021 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Associate Professor Patrick McGovern (London School of Economics). Abstract Döllinger, D. 2021. From Custom to Code. A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football. 167 pp. Uppsala: Department of Sociology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2879-1. The present study is a sociological interpretation of the emergence of modern football between 1733 and 1864. It focuses on the decades leading up to the foundation of the Football Association in 1863 and observes how folk football gradually develops into a new form which expresses itself in written codes, clubs and associations. In order to uncover this transformation, I have collected and analyzed local and national newspaper reports about football playing which had been published between 1733 and 1864. I find that folk football customs, despite their great local variety, deserve a more thorough sociological interpretation, as they were highly emotional acts of collective self-affirmation and protest. At the same time, the data shows that folk and early association football were indeed distinct insofar as the latter explicitly opposed the evocation of passions, antagonistic tensions and collective effervescence which had been at the heart of the folk version. Keywords: historical sociology, football, custom, culture, community Dominik Döllinger, Department of Sociology, Box 624, Uppsala University, SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. -

The Atlas of Digitised Newspapers and Metadata: Reports from Oceanic Exchanges

THE ATLAS OF DIGITISED NEWSPAPERS AND METADATA: REPORTS FROM OCEANIC EXCHANGES M. H. Beals and Emily Bell with additional contributions by Ryan Cordell, Paul Fyfe, Isabel Galina Russell, Tessa Hauswedell, Clemens Neudecker, Julianne Nyhan, Mila Oiva, Sebastian Padó, Miriam Peña Pimentel, Lara Rose, Hannu Salmi, Melissa Terras, and Lorella Viola and special thanks to Seth Cayley (Gale), Steven Claeyssens (KB), Huibert Crijns (KB), Nicola Frean (NLNZ), Julia Hickie (NLA), Jussi-Pekka Hakkarainen (NLF), Chris Houghton (Gale), Melanie Lovell-Smith (NLNZ), Minna Kaukonen (NLF), Luke McKernan (BL), Chris McPartlanda (NLA), Maaike Napolitano (KB), Tim Sherratt (University of Canberra) and Emerson Vandy (NLNZ) Document: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.11560059 Dataset: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.11560110 Disclaimer: This project was made possible by funding from Digging into Data, Round Four (HJ-253589). Although we have directly consulted with the various institutions discussed in this report, the final findings, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the discussed database providers or the contributors’ host institutions. Executive Summary Between 2017 and 2019, Oceanic Exchanges (http://www.oceanicexchanges.org), funded through the Transatlantic Partnership for Social Sciences and Humanities 2016 Digging into Data Challenge (https://diggingintodata.org), brought together leading efforts in computational periodicals research from six countries—Finland, Germany, Mexico, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States—to examine patterns of information flow across national and linguistic boundaries. Over the past thirty years, national libraries, universities and commercial publishers around the world have made available hundreds of millions of pages of historical newspapers through mass digitisation and currently release over one million new pages per month worldwide. -

James Horsburgh (1786-1860) Shipbuilder in Dundee

1 James Horsburgh (1786-1860) Shipbuilder in Dundee A headstone in the Howff Cemetery, Dundee. By Dr D Horsburgh On Friday 2 May 1947 a letter was published in the Dundee Courier which read: “I am collecting information about the shipbuilding of Dundee in the days of the old “wooden walls,” and find that there is very little authentic literature about it...I should also appreciate any information about...pioneer firms like James Smart, Garland & Horsburgh, and Kewans & Horn, who flourished in the early years of the last century.” Although since 1947 historians have discussed the general trade and shipping of Dundee, little detailed research has been published about the shipbuilders. In 2013 I privately published the non-commercial work: Born of Forth & Tay A Branch of the Horsburgh Family in Dundee and Fife, from which the following edited account of James Horsburgh, who is mentioned above, is taken. I hope that other researchers will look favourably on this work as a useful contribution to Dundee‟s shipbuilding history. 2 Summary of Contents 3-4 James Horsburgh, family background, shipbuilders in Anstruther Easter, relationship with Agnes Reekie (Carnbee) and wife Mary Watson (St Andrews) 4-5 Dundee shipbuilders in the early 19th century 5-7 James Horsburgh and the Caledonian Mason Lodge of Dundee 1814-1825 9-11 Shipwrights‟ strikes and Dundee trade unionism 1824-1826 11-19 New Shipwright Building Company of Dundee at Trades‟ Lane and Seagate, activities, members and commissions 1826-1831 19-31 Garland and Horsburgh shipbuilders, activities -

A Poem by Philocalos Celebrating Hume's Return to Edinburgh Donald Livingston

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 10 1989 A Poem by Philocalos Celebrating Hume's Return to Edinburgh Donald Livingston Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Livingston, Donald (1989) "A Poem by Philocalos Celebrating Hume's Return to Edinburgh," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 24: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol24/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Donald Livingston A Poem by Philocalos Celebrating Hume's Return to Edinburgh David Hume left Edinburgh in 1763 to serve as secretary to the Em bassy in France under Lord Hertford. For two years he enjoyed the adula tion of French society for his achievements in philosophy and history. He returned to London January, 1766, and spent a year tangled in the Rousseau affair. Early in 1767 he took the position of Under-Secretary of State to the Northern Department, which he held until January 1768. He remained in London for nineteen more months where he saw the begin ning of the Wilkes and Liberty riots, which lasted on and off for three years and seemed to threaten the rule of law. It is during this time that Hume's letters begin to take on a prophetic note of alarm about the sta bility of British constitutional order, and how English political fanaticism and the massive public debt, brought on by Pitt's mercantile wars, may bring on political chaos. -

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook Illustrations of Edinburgh and other material collected by Sir Daniel Wilson, some of which he used in his Memorials of Edinburgh in the olden time (Edin., 1847). The following list gives possible sources for the items; some prints were published individually as well as appearing as part of larger works. References are also given to their use in Memorials. Quick-links within this list: Box I Box II Box III Abbreviations and notes Arnot: Hugo Arnot, The History of Edinburgh (1788). Bann. Club: Bannatyne Club. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated: W. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated in a series of views [ca. 1840]. Beauties of Scotland: R. Forsyth, The Beauties of Scotland (1805-8). Billings: R.W. Billings, The Baronial and ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1845-52). Black (1843): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1843). Black (1859): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1859). Edinburgh and Mid-Lothian (1838). Drawings by W.B. Scott, engraved by R. Scott. Some of the engravings are dated 1839. Edinburgh delineated (1832). Engravings by W.H. Lizars, mostly after drawings by J. Ewbank. They are in two series, each containing 25 numbered prints. See also Picturesque Views. Geikie, Etchings: Walter Geikie, Etchings illustrative of Scottish character and scenery, new edn [1842?]. Gibson, Select Views: Patrick Gibson, Select Views in Edinburgh (1818). Grose, Antiquities: Francis Grose, The Antiquities of Scotland (1797). Hearne, Antiquities: T. Hearne, Antiquities of Great Britain illustrated in views of monasteries, castles and churches now existing (1807). Heriot’s Hospital: Historical and descriptive account of George Heriot’s Hospital. With engravings by J. -

Caledonian Mercury

Num. 4079 The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh, Tuesday, December 2, 1746 Such as have been furnished with this Paper by Mr. WALTER FOGGO Principal Clerk in the Gen- eral Post-Office, Edinburgh, are hereby desired to send up what they are resting as soon as pos- sible. And those who are served from the Printing-house, will be pleased to pay what they are owing. Since our last arrived a Holland Mail. jects against ths Province: But we question their do- ing any thing worth speaking of this Season. Howev- From Wye’s Letter, London, Nov. 27. er, we have provided against the worst that may hap- ROM the Hague December 1st, they tell us, pen. Our Army receives Reinforcements every Day, they are in Pain there, for some Advices and 20 Battalions are expected from Franche Comte touching the Affairs of Provence, for which by the End of this Month, which, as we are assured, Place, they write from Paris, that 31 Battal- are followed by 50 more. This City is well prepared ions from Alsace and Franche Compte, are for an Attack, and our Coasts are well guarded. Fin full March. Paris, Nov. 25. The last Letters from Provence say, An Appeal of the Earl of Lauderdale was Yesterday that only some Detachments of the Combin’d Army of presented to the House of Lords and read, complain- Austrians and Piedmonteze had passed the Var, but ing of several Interlocutors of the Lords of Session in that they were not able to maintain their Footing on Scotland.—Read two Petitions for private Bills, which this Side of the River; and that the last Division of the were referred to the Judges, who are to make Report Austrian Troops, which were coming from Lombardy thereof. -

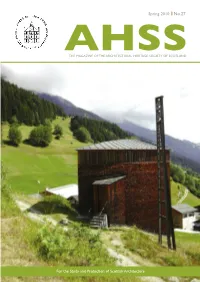

Spring 2010 No.27

Spring 2010 No.27 ATHE MAGAZINE OF THHE ARCHITECTURAL HESRITAGE SOCIETYS OF SCOTLAND For the Study and Protection of Scottish Architecture 2 introduction AHSS contents Magazine Spring 2010 (No. 27) Obituary Collation: Mary Pitt and 03 Carmen Moran Reviews Editor: Mark Cousins 07 News from the Glasite Meeting House Design: Pinpoint Scotland Ltd. 08 News President: The Dowager Countess of 11 Heritage Lottery Fund Wemyss and March Chairman: Peter Drummond 13 Projects Volunteer Editorial Assistants: Walking in the Air Anne Brockington Chris Judson 15 RCAHMS Philip Graham The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland NATIONAL OFFICE Edited by Veronica Fraser. The Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland HS Listing The Glasite Meeting House 20 33 Barony Street Edinburgh 21 Other Organisations EH3 6NX 30 Talking Point Tel: 0131 557 0019 Contemporary architecture in the historic environment. Fax: 0131 557 0049 Email: [email protected] My Favourite Building www.ahss.org.uk 33 Investigation The Rural Church Copyright © AHSS and contributors, 2010 The opinions expressed by contributors in this 36 Consultations publication are not necessarily those of the AHSS. Edited highlights of AHSS responses to recent consultations. The Society apologises for any errors or inadvertent infringements of copyright. 38 Reviews The AHSS gratefully acknowledges assistance from the Royal Commission on the Ancient and 43 Education Historical Monuments of Scotland towards the production costs of the AHSS Magazine. 50 National activities 50 Group activities 54 Group casework 59 Membership 60 Diary CALL FOR CONTRIBUTIONS If you would like to contribute to future issues of AHSS magazine, please contact the editor at [email protected] Submission deadline for the Autumn 2010 issue is 24 July 2010 . -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. The Social Life of Paper in Edinburgh c.1770 – c.1820 Claire L. Friend Ph.D. The University of Edinburgh 2016 Declaration I confirm that the following thesis has been composed by me, and is completely my own work. This thesis grew out of an essay I submitted towards the degree of MSc at the University of Edinburgh in the 2008-9 academic year titled ‗The Social Life of Paper‘. Claire L. Friend 31st March 2016 ~ 2 ~ Abstract Previous research on paper history has tended to be conducted from an economic perspective and/or as part of the field of book history within a broadly literary framework. This has resulted in understandings of paper history being book-centric and focused on production. We now have a great deal of knowledge about the physical process of hand paper-making, a good knowledge of the actors involved and where in the country paper was manufactured, but there is still very little scholarly discussion of the people, processes and practices associated with paper outside of the mill. -

THE HOME of the ROYAL SOCIETY of EDINBURGH Figures Are Not Available

THE HOME OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH Figures are not available Charles D Waterston The bicentennial history of the Royal Society of Edinburgh1, like previous accounts, was rightly concerned to record the work and achievements of the Society and its Fellows. Although mention is made of the former homes and possessions of the Society, these matters were incidental to the theme of the history which was the advancement of learning and useful knowledge, the chartered objectives of the Society. The subsequent purchases by the Society of its premises at 22–28 George Street, Edinburgh, have revealed a need for some account of these fine buildings and of their contents for the information of Fellows and to enhance the interest of many who will visit them. The furniture so splendidly displayed in 22–24 George Street dates, for the most part, from periods in our history when the Society moved to more spacious premises, or when expansion and refurbishment took place within existing accommodation. In order that these periods of acquisition may be better appreciated it will be helpful to give a brief account of the rooms which it formerly occupied before considering the Society's present home. Having no personal knowledge of furniture, I acknowledge my indebtedness to Mr Ian Gow of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland and Mr David Scarratt, Keeper of Applied Art at the Huntly House Museum of Edinburgh District Council Museum Service for examining the Society's furniture and for allowing me to quote extensively from their expert opinions. -

Download Download

CONTENTS OF APPENDIX. Page I. List of Members of the Society from 1831 to 1851:— I. List of Fellows of the Society,.................................................. 1 II. List of Honorary Members....................................................... 8 III. List of Corresponding Members, ............................................. 9 II. List of Communications read at Meetings of the Society, from 1831 to 1851,............................................................... 13 III. Listofthe Office-Bearers from 1831 to 1851,........................... 51 IV. Index to the Names of Donors............................................... 53 V. Index to the Names of Literary Contributors............................. 59 I. LISTS OF THE MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF THE ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND. MDCCCXXXL—MDCCCLI. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN, PATRON. No. I.—LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. (Continued from the AppenHix to Vol. III. p. 15.) 1831. Jan. 24. ALEXANDER LOGAN, Esq., London. Feb. 14. JOHN STEWARD WOOD, Esq. 28. JAMES NAIRWE of Claremont, Esq., Writer to the Signet. Mar. 14. ONESEPHORUS TYNDAL BRUCE of Falkland, Esq. WILLIAM SMITH, Esq., late Lord Provost of Glasgow. Rev. JAMES CHAPMAN, Chaplain, Edinburgh Castle. April 11. ALEXANDER WELLESLEY LEITH, Esq., Advocate.1 WILLIAM DAUNEY, Esq., Advocate. JOHN ARCHIBALD CAMPBELL, Esq., Writer to the Signet. May 23. THOMAS HOG, Esq.2 1832. Jan. 9. BINDON BLOOD of Cranachar, Esq., Ireland. JOHN BLACK GRACIE, Esq.. Writer to the Signet. 23. Rev. JOHN REID OMOND, Minister of Monfcie. Feb. 27. THOMAS HAMILTON, Esq., Rydal. Mar. 12. GEORGE RITCHIE KINLOCH, Esq.3 26. ANDREW DUN, Esq., Writer to the Signet. April 9. JAMES USHER, Esq., Writer to the Signet.* May 21. WILLIAM MAULE, Esq. 1 Afterwards Sir Alexander W. Leith, Bart. " 4 Election cancelled. 3 Resigned. VOL. IV.—APP. A 2 LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. -

The Highland Clans of Scotland

:00 CD CO THE HIGHLAND CLANS OF SCOTLAND ARMORIAL BEARINGS OF THE CHIEFS The Highland CLANS of Scotland: Their History and "Traditions. By George yre-Todd With an Introduction by A. M. MACKINTOSH WITH ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS, INCLUDING REPRODUCTIONS Of WIAN'S CELEBRATED PAINTINGS OF THE COSTUMES OF THE CLANS VOLUME TWO A D. APPLETON AND COMPANY NEW YORK MCMXXIII Oft o PKINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE THE MACDONALDS OF KEPPOCH 26l THE MACDONALDS OF GLENGARRY 268 CLAN MACDOUGAL 278 CLAN MACDUFP . 284 CLAN MACGILLIVRAY . 290 CLAN MACINNES . 297 CLAN MACINTYRB . 299 CLAN MACIVER . 302 CLAN MACKAY . t 306 CLAN MACKENZIE . 314 CLAN MACKINNON 328 CLAN MACKINTOSH 334 CLAN MACLACHLAN 347 CLAN MACLAURIN 353 CLAN MACLEAN . 359 CLAN MACLENNAN 365 CLAN MACLEOD . 368 CLAN MACMILLAN 378 CLAN MACNAB . * 382 CLAN MACNAUGHTON . 389 CLAN MACNICOL 394 CLAN MACNIEL . 398 CLAN MACPHEE OR DUFFIE 403 CLAN MACPHERSON 406 CLAN MACQUARIE 415 CLAN MACRAE 420 vi CONTENTS PAGE CLAN MATHESON ....... 427 CLAN MENZIES ........ 432 CLAN MUNRO . 438 CLAN MURRAY ........ 445 CLAN OGILVY ........ 454 CLAN ROSE . 460 CLAN ROSS ........ 467 CLAN SHAW . -473 CLAN SINCLAIR ........ 479 CLAN SKENE ........ 488 CLAN STEWART ........ 492 CLAN SUTHERLAND ....... 499 CLAN URQUHART . .508 INDEX ......... 513 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Armorial Bearings .... Frontispiece MacDonald of Keppoch . Facing page viii Cairn on Culloden Moor 264 MacDonell of Glengarry 268 The Well of the Heads 272 Invergarry Castle .... 274 MacDougall ..... 278 Duustaffnage Castle . 280 The Mouth of Loch Etive . 282 MacDuff ..... 284 MacGillivray ..... 290 Well of the Dead, Culloden Moor . 294 Maclnnes ..... 296 Maclntyre . 298 Old Clansmen's Houses 300 Maclver .... -

Inventory Acc.12092 Papers of the Family of Skene of Rubislaw Related

Inventory Acc.12092 Papers of the family of Skene of Rubislaw related Scottish families, and the family of Sir Walter Scott National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland This collection consists of more than 3000 documents, dating from the 1420s to 1980s, mainly relating to the family of Skene of Rubislaw (near Aberdeen). At its centre are the papers of James Skene (1775-1864), artist and friend of Sir Walter Scott. Skene corresponded with notable individuals in the cultural circles of his day and was connected with such organizations as the Royal Institution, the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the Institute for the Encouragement of the Fine Arts in Scotland, the Board of Trustees for Manufacturers, and the Bannatyne Club, among others. The archive was formerly in the possession of Major P.I.C. Payne, of Minehead, in Somerset, who acquired the material by purchase from various sources. Some of Major Payne’s own papers relating to the collection from the 1960s, 70s and 80s are included (folders 102-107). Major Payne provided individual descriptions of a portion of the earlier Skene family papers (folders 1-10). These descriptions are listed in the Appendix to this inventory. Folder 10 includes some letters of James Skene himself. Other related families (folders 22-36) include Moir of Stoneywood (the family of James Skene’s mother, Jane), the Forbes family (that of Skene’s wife, Jane, daughter of Sir William Forbes of Pitsligo), Russell of Aden, Keith of Ludquhairn, Gordon of Balgown, Ramsay of Invernellie and Peterhead, and Skene of Halyards and Curriehill.