Scotland's Castles Rescued, Rebuilt and Reoccupied, 1945 - 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Members' Centre and Friends' Group Events

MEMBERS’ CENTRE AND FRIENDS’ GROUP EVENTS AUTUMN/WINTER 2019 Joining a centre or group is a great way to get more out of your membership and learn more about the work of the Trust. All groups also raise vital funds for Trust places and projects across the country. Please note that most groups charge a small annual membership subscription, separate to your Trust membership. The groups host a range of lectures, outings, social events and tours for their members throughout the year. For more information please contact each group directly. ABERDEEN AND DISTRICT MEMBERS’ Thursday 13 February, 2.00pm: Talk by Dr Thursday 3 October, 2.15pm: Annual CENTRE (SC000109) Fiona-Jane Brown “Forgotten Fittie” at the general meeting, followed by a talk from Ben Aberdeen Maritime Museum, Shiprow. Judith Falconer, Programme Secretary Reiss of the Morton Photography Project, which has supported the Trust in curating Tel: 01224 938150 Tuesday 17 March, 7.30pm: Annual general and conserving its photographic collection. Email: [email protected] meeting followed by a talk by Gordon Guide Hall, Myre Car Park, Forfar. Murdoch “Join the National Trust….. and see Booking is essential for events marked * the world” at the Aberdeenshire Cricket October date TBC: Visit to Drum Castle to There is a charge for guests attending talks. Club, Morningside Road. see the “A Considered Place” exhibition. For further information, please contact the Tuesday 17 September, 7.30pm: Talk by * Day excursion in early May TBC Membership Secretary. Finlay McKichan “Lord Seaforth: Highland landowner, Caribbean governor and slave * Annual holiday in early June TBC Saturday 2 November, 10–12 noon: Coffee owner” at the Aberdeenshire Cricket Club, morning at the Old Parish Church Hall, Morningside Road. -

Fnh Journal Vol 28

the Forth Naturalist and Historian Volume 28 2005 Naturalist Papers 5 Dunblane Weather 2004 – Neil Bielby 13 Surveying the Large Heath Butterfly with Volunteers in Stirlingshire – David Pickett and Julie Stoneman 21 Clackmannanshire’s Ponds – a Hidden Treasure – Craig Macadam 25 Carron Valley Reservoir: Analysis of a Brown Trout Fishery – Drew Jamieson 39 Forth Area Bird Report 2004 – Andre Thiel and Mike Bell Historical Papers 79 Alloa Inch: The Mud Bank that became an Inhabited Island – Roy Sexton and Edward Stewart 105 Water-Borne Transport on the Upper Forth and its Tributaries – John Harrison 111 Wallace’s Stone, Sheriffmuir – Lorna Main 113 The Great Water-Wheel of Blair Drummond (1787-1839) – Ken MacKay 119 Accumulated Index Vols 1-28 20 Author Addresses 12 Book Reviews Naturalist:– Birds, Journal of the RSPB ; The Islands of Loch Lomond; Footprints from the Past – Friends of Loch Lomond; The Birdwatcher’s Yearbook and Diary 2006; Best Birdwatching Sites in the Scottish Highlands – Hamlett; The BTO/CJ Garden BirdWatch Book – Toms; Bird Table, The Magazine of the Garden BirthWatch; Clackmannanshire Outdoor Access Strategy; Biodiversity and Opencast Coal Mining; Rum, a landscape without Figures – Love 102 Book Reviews Historical–: The Battle of Sheriffmuir – Inglis 110 :– Raploch Lives – Lindsay, McKrell and McPartlin; Christian Maclagan, Stirling’s Formidable Lady Antiquary – Elsdon 2 Forth Naturalist and Historian, volume 28 Published by the Forth Naturalist and Historian, University of Stirling – charity SCO 13270 and member of the Scottish Publishers Association. November, 2005. ISSN 0309-7560 EDITORIAL BOARD Stirling University – M. Thomas (Chairman); Roy Sexton – Biological Sciences; H. Kilpatrick – Environmental Sciences; Christina Sommerville – Natural Sciences Faculty; K. -

European Elections Why Vote? English

Europea2n E0lecti1ons9 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT THE EUROPEAN ELECTIONS WHY VOTE? ENGLISH United Kingdom Results of the 23 May 2019 European elections Show 10 entries Search: Trend European Number of Percentage of Number of Political parties compared with affiliation votes votes seats 2014 Brexit Party EFDD 30.74% 29 ↑ Liberal Democrat Party Renew Europe 19.75% 16 ↑ Labour Party S&D 13.72% 10 ↓ Green Party Greens/EFA 11.76% 7 ↑ Conservative Party ECR 8.84% 4 ↓ Scottish National Party Greens/EFA 3.50% 3 ↑ Plaid Cymru, Party of Greens/EFA 0.97% 1 ↑ Wales Sinn Fein GUE/NGL 0.62% 1 = Democratic Unionist 0.59% 1 = Party Alliance Party 0.5% 1 ↑ Showing 1 to 10 of 10 entries Previous Next List of MEPs Rory Palmer Labour Party S&D Claude Ajit Moraes Labour Party S&D Sebastian Thomas Dance Labour Party S&D Jude Kirton-Darling Labour Party S&D Theresa Mary Griffin Labour Party S&D Julie Carolyn Ward Labour Party S&D John Howarth Labour Party S&D Jacqueline Margarete Jones Labour Party S&D Neena Gill Labour Party S&D Richard Graham Corbett Labour Party S&D Barbara Ann Gibson Liberal Democrats Renew Europe Lucy Kathleen Nethsingha Liberal Democrats Renew Europe William Francis Newton Dunn Liberal Democrats Renew Europe Irina Von Wiese Liberal Democrats Renew Europe Dinesh Dhamija Liberal Democrats Renew Europe Luisa Manon Porritt Liberal Democrats Renew Europe Chris Davies Liberal Democrats Renew Europe Jane Elisabeth Brophy Liberal Democrats Renew Europe Sheila Ewan Ritchie Liberal Democrats Renew Europe Catherine Zena Bearder Liberal Democrats -

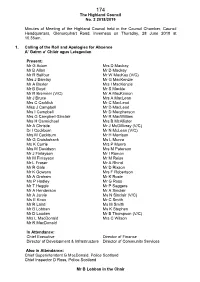

Volume of Minutes

174 The Highland Council No. 2 2018/2019 Minutes of Meeting of the Highland Council held in the Council Chamber, Council Headquarters, Glenurquhart Road, Inverness on Thursday, 28 June 2018 at 10.35am. 1. Calling of the Roll and Apologies for Absence A’ Gairm a’ Chlàir agus Leisgeulan Present: Mr G Adam Mrs D Mackay Mr B Allan Mr D Mackay Mr R Balfour Mr W MacKay (V/C) Mrs J Barclay Mr G MacKenzie Mr A Baxter Mrs I MacKenzie Mr B Boyd Mr S Mackie Mr R Bremner (V/C) Mr A MacKinnon Mr J Bruce Mrs A MacLean Mrs C Caddick Mr C MacLeod Miss J Campbell Mr D MacLeod Mrs I Campbell Mr D Macpherson Mrs G Campbell-Sinclair Mr R MacWilliam Mrs H Carmichael Mrs B McAllister Mr A Christie Mr J McGillivray (V/C) Dr I Cockburn Mr N McLean (V/C) Mrs M Cockburn Mr H Morrison Mr G Cruickshank Ms L Munro Ms K Currie Mrs P Munro Mrs M Davidson Mrs M Paterson Mr J Finlayson Mr I Ramon Mr M Finlayson Mr M Reiss Mr L Fraser Mr A Rhind Mr R Gale Mr D Rixson Mr K Gowans Mrs F Robertson Mr A Graham Mr K Rosie Ms P Hadley Mr G Ross Mr T Heggie Mr P Saggers Mr A Henderson Mr A Sinclair Mr A Jarvie Ms N Sinclair (V/C) Ms E Knox Mr C Smith Mr R Laird Ms M Smith Mr B Lobban Ms K Stephen Mr D Louden Mr B Thompson (V/C) Mrs L MacDonald Mrs C Wilson Mr R MacDonald In Attendance: Chief Executive Director of Finance Director of Development & Infrastructure Director of Community Services Also in Attendance: Chief Superintendent G MacDonald, Police Scotland Chief Inspector D Ross, Police Scotland Mr B Lobban in the Chair 175 Apologies for absence were intimated on behalf of Mr I Brown, Mr C Fraser, Mr J Gordon, Mr J Gray and Mrs T Robertson. -

The Actual Reality Trust Ardentinny Outdoor Education Centre Argyll Please Reply To: 1/1 Barcapel Avenue Newton Mearns G77 6QJ

PROPOSED REPORT BY THE STANDARDS COMMISSIONER ON THE COMPLAINT AGAINST COUNCILLOR MICHAEL BRESLIN (LA/AB/1758/JM) Witness Statement by Dr C M Mason, MBE Appendix 4 The Actual Reality Trust Ardentinny Outdoor Education Centre Argyll Please reply to: 1/1 Barcapel Avenue Newton Mearns G77 6QJ Telephone 0141 384 7979 Mobile 0781 585 1775 email: [email protected] 30 November 2013 Mrs Sally Loudon Chief Executive Argyll and Bute Council by email Dear Mrs. Loudon Audit Scotland and Castle Toward - clarification As you know, Mr. McKinlay copied me into the email he sent you yesterday afternoon. I do not think there can be any doubt that Mr. McKinlay has now very clearly put on record three important facts: 1. The scope of Audit Scotland’s work on Actual Reality and Castle Toward was limited to the sales of Castle Toward and Ardentinny; and it was only the results of that work which were given in the annual audit report to elected members and to the Controller of Audit. 2. You have known about this limitation all along because the scope of Audit Scotland’s work was agreed in an exchange of letters between you and Fiona Mitchell-Knight in February this year. 3. Audit Scotland accordingly did not carry out any detailed audit work on the allegations that we have made about the closure of Castle Toward in 2009 and they are “therefore not in a position to comment on the substance or otherwise of them”. My purpose in writing to you now is to ask you to account for the claims made in the name of the Council, that Audit Scotland have supported, confirmed, or validated Council officers’ position that our allegations about the events of 2009 have no substance. -

Newsletter Contents 07-08

Newsletter No 28 Summer/Autumn 2008 He is currently working on a book on the nineteenth- From the Chair century travel photographer Baron Raimund von Stillfried. Welcome to the first of our new shorter-but- hopefully-more-frequent newsletters! The main casualty has been the listings section, which is no New SSAH Grant Scheme longer included. Apologies to those of you who found this useful but it takes absolutely ages to compile and As you’ll know from last issue, we recently launched a the information should all be readily available scheme offering research support grants from £50 to elsewhere. Otherwise you should still find the same £300 to assist with research costs and travel mix of SSAH news and general features – if you have expenses. We’re delighted to say that several any comments on the newsletter or would like to applications have already been received and so far we contribute to future issues, please let us know! have awarded five grants to researchers from around Now, let’s waste no more time and get on the world. Here we present the first two reports with the latest news… from grant recipients on how the money has been Matthew Jarron spent. Committee News Gabriel Montua, Humboldt-Universität Berlin, Germany As promised last issue, we present a profile of our newest committee member: The generous SSAH grant of £206.96 enabled me to cover my travel expanses to the Scottish National Luke Gartlan Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh, where I consulted item GMA A42/1/GKA008 from the Luke is a lecturer in the School of Art History at the Gabrielle Keiller Collection: letters exchanged University of St Andrews, where he currently teaches between Salvador Dalí and André Breton. -

Excavations at Bothwell Castle, North Lanarkshire

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 127 (1997), 687-695 Excavation t Bothwelsa l Castle, North Lanarkshire John Lewis* ABSTRACT The following report describes two small-scale excavations (in 1987-8 and 1991) within the castle enclosure and a watching brief carried out in 1993 during the topsail clearance which preceded the installation of a new car park some 100 m east of the castle. Trenching to the immediate east of the postern revealed traces of what may have been an extension to the south range; and a possible robber trench, perhaps associated with the gatehouse, was uncovered just inside the modern entrance to the castle. The project was funded by Historic Scotland (former SDD/HBM). INTRODUCTION Standin gwoodee th hig n ho d nort hRivee banth f rko outskirtClydee th towe n th o f , nf o so Uddingston and some 13 km south-east of Glasgow (illus 1), Bothwell Castle (NGR: NS 688 593) retains the air of the formidable stronghold that it once was (illus 2). Begun in the mid- or late 13th centur Waltey Williamyb n so f Mora s ro originae hi th r , yo l desigcastle neves th f enwa o r brought to fruition, probably because of the depredations of the Wars of Independence in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. It was not until the early 15th century, following many turbulent years during which the castle changed hands on several occasions, that the enclosure was finally completed somewhaa n the y o wore b ;s nth kwa t reduced scale from that originally conceived (Simpson 1958,14). -

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide 2 Introduction Scotland is surrounded by coastal water – the North Sea, the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, there are also numerous bodies of inland water including rivers, burns and about 25,000 lochs. Being safe around water should therefore be a key priority. However, the management of water safety is a major concern for Scotland. Recent research has found a mixed picture of water safety in Scotland with little uniformity or consistency across the country.1 In response to this research, it was suggested that a framework for a water safety policy be made available to local authorities. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) has therefore created this document to assist in the management of water safety. In order to support this document, RoSPA consulted with a number of UK local authorities and organisations to discuss policy and water safety management. Each council was asked questions around their own area’s priorities, objectives and policies. Any policy specific to water safety was then examined and analysed in order to help create a framework based on current practice. It is anticipated that this framework can be localised to each local authority in Scotland which will help provide a strategic and consistent national approach which takes account of geographical areas and issues. Water Safety Policy in Scotland— A Guide 3 Section A: The Problem Table 1: Overall Fatalities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 Data from National Water Safety Forum, WAID database, July 14 In recent years the number of drownings in Scotland has remained generally constant. -

Inside This Month

September 2010 Volume 16 Issue 8 News and Views The Merkinch community newsletter, entirely written and produced in the Merkinch Dolphins turn out to visit LNR’s open day Inside this month: Near-school parking concerns – page 3 Crackdown on debt collectors – page 5 LNR and ABOVE… Oh look! See the dolphins, says Cllr Bet Croc Dock McAllister as she arrived to officially open the refurbished Old Ferry Ticket Office on the Nature pictures Reserve’s Showcase Day last month. Three dolphins – pp 7, 10 turned up just on time for the start of the annual event much to everyone’s delight. More coverage of the day’s activities on page 10. Freerunners’ first All the latest LEFT… A highlight of the Showcase Day’s events sports news was the first Scottish Freerunners’ Jam which was and pics – held in the Westfield. Participants came from all over Scotland. Freerunning requires great gymnastic skills pp 12, 13 and the ability to land safely. More on page 13. 2 News & Views Helpline Albyn backs Enterprise to AGE Concern – 0800 731 4931. boost IT training scheme ALCOHOL, Inverness Council on – 34 PEOPLE living in Merkinch will now have Tomnahurich St, tel 220995. better access to IT training thanks to a CHILDLINE – 0800 1111. Free contribution of £9,000 from Albyn Housing confidential advice 24 hours a day. Society’s Wider Role Fund. Citizens Advice Bureau – Advice line, 08 This fund, which is possible thanks to the 444 994111; Appointments, 01463 237664 Scottish Government, exists to address poverty and neighbourhood decline by COMMUNITY CENTRE – 239563. -

Castle Toward

Castle Toward - Innellan - Dunoon - Sandbank - Kilmun - Ardentinny - Glenfinart Schooldays Mondays to Fridays - Operated by West Coast Motors 01586 552319 489 Service Number: 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 489 Codes: v m v m v m ThF Castle Toward 0809 TPS 1017 1217 Toward Lighthouse 0603 0647 0710 0752 0814 0902 0922 0922 1022 1122 1122 1222 1322 1322 Newton Park 0607 0651 0714 0756 0818 0840 0906 0926 0926 1026 1126 1126 1226 1326 1326 Innellan, Sandy Beach 0608 0652 0715 0757 0819 0819 0841 0907 0927 0927 1027 1127 1127 1227 1327 1327 Innellan Primary School I I I I I I 0845 I 0930 0930 I I I I 1330 1330 Innellan, Pier 0611 0655 0718 0800 0822 0822 0910 I I 1030 1130 1130 1230 I I Dunoon, Balaclava Garage 0616 0700 0723 0803 0827 0827 WB 0915 0935 0935 1035 1135 1135 1235 1335 1335 Dunoon, Ferry Terminal 0624 0708 0731 0813 0835 0835 0835 0923 0943 0943 1043 1143 1143 1243 1343 1343 John Street 0628 0712 0817 I I I 0947 0947 1047 1147 1147 1247 1347 1347 Dunoon, Ferry Terminal 0630 0714 0819 I I I 0949 0949 1049 1149 1149 1249 1349 1349 Dunoon, Ferry Terminal 0630 0700 0715 0820 I I I 0850 0950 0950 1050 1150 1150 1250 1350 1350 Dunoon, General Hospital 0634 0704 0719 0824 0839 0839 0839 0854 0954 0954 1054 1154 1154 1254 1354 1354 Dunoon, Grammar School 0635 0705 0720 0825 0840 0840 0840 0855 0955 0955 1055 1155 1155 1255 1355 1355 1445 Kirn Brae at Marine Parade 0637 0707 0722 0827 0857 0957 0957 1057 1157 1157 1257 1357 1357 1447 Hunter's Quay, Ferry Terminal 0639 0709 0724 0828 0859 0959 -

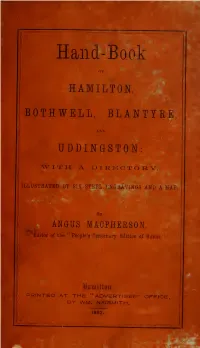

Hand-Book of Hamilton, Bothwell, Blantyre, and Uddingston. with a Directory

; Hand-Book HAMILTON, BOTHWELL, BLANTYRE, UDDINGSTON W I rP H A DIE EJ C T O R Y. ILLUSTRATED BY SIX STEEL ENGRAVINGS AND A MAP. AMUS MACPHERSON, " Editor of the People's Centenary Edition of Burns. | until ton PRINTED AT THE "ADVERTISER" OFFICE, BY WM. NAISMITH. 1862. V-* 13EFERKING- to a recent Advertisement, -*-*; in which I assert that all my Black and Coloured Cloths are Woaded—or, in other wards, based with Indigo —a process which,, permanently prevents them from assuming that brownish appearance (daily apparent on the street) which they acquire after being for a time in use. As a guarantee for what I state, I pledge myself that every piece, before being taken into stock, is subjected to a severe chemical test, which in ten seconds sets the matter at rest. I have commenced the Clothing with the fullest conviction that "what is worth doing is worth doing well," to accomplish which I shall leave " no stone untamed" to render my Establishment as much a " household word " ' for Gentlemen's Clothing as it has become for the ' Unique Shirt." I do not for a moment deny that Woaded Cloths are kept by other respectable Clothiers ; but I give the double assurance that no other is kept in my stock—a pre- caution that will, I have no doubt, ultimately serve my purpose as much as it must serve that of my Customers. Nearly 30 years' experience as a Tradesman has convinced " me of the hollowness of the Cheap" outcry ; and I do believe that most people, who, in an incautious moment, have been led away by the delusive temptation of buying ' cheap, have been experimentally taught that ' Cheapness" is not Economy. -

Society of Antiquaries Portmahomack on Tarbat Ness: Changing

Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Portmahomack on Tarbat Ness: Changing Ideologies in North-East Scotland, Sixth to Sixteenth Century AD by Martin Carver, Justin Garner-Lahire and Cecily Spall ISBN: 978-1-908332-09-7 (hbk) • ISBN: 978-1-908332-16-5 (PDF) Except where otherwise noted, this work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work and to adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Carver, M, Garner-Lahire, J & Spall, C 2016 Portmahomack on Tarbat Ness: Changing Ideologies in North-East Scotland, Sixth to Sixteenth Century AD. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Available online via the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland: https://doi.org/10.9750/9781908332165 Please note: Please note that the illustrations listed on the following page are not covered by the terms of the Creative Commons license and must not be reproduced without permission from the listed copyright holders. Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders for all third-party material reproduced in this volume. The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland would be grateful to hear of any errors or omissions. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Portmahomack on Tarbat Ness: Changing Ideologies in North-East Scotland, Sixth to Sixteenth Century AD by Martin Carver, Justin Garner-Lahire and Cecily Spall ISBN: 978-1-908332-09-7 (hbk) • ISBN: 978-1-908332-16-5 We are grateful to the following for permission to reproduce images, and remind readers that the following third-party material is not covered by the Creative Commons license.