Musical and Theatrical Declamation in Richard Wagner's Works and A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Zwischen Nottaufe Und Nottrauung – Einblicke in Das Leben Felix Mottls

Clarissa Höschel Zwischen Nottaufe und Nottrauung – Einblicke in das Leben Felix Mottls . Eine Hommage zu seinem 160. Geburtstag In der Münchener Musikgeschichte hat er längst seinen festen Platz – der aus Unter St. Veit (Wien) stammende Felix Mottl (1856–1911), der von 1904 bis zu seinem Tod als Generalmusikdirektor an der Isar wirkte. Der Mensch hinter dem Musiker ist hingegen nur wenigen bekannt; selbst die anlässlich seines 150. Geburtstages erschienene Biografe1 porträtiert in erster Linie den Musi- ker. Auch anlässlich seines 100. Todestages (2011) wurde, wenn überhaupt, an den Generalmusikdirektor erinnert – Anlass genug, einige Facetten des Menschen und Mannes Felix Mottl vorzustellen. Gelingen kann ein solches Unterfangen anhand der tagebuchartigen Aufzeich- nungen, die Mottl 1873 be- gonnen hat und die heute in der Bayerischen Staats- bibliothek in München als Teil des Nachlasses Felix Abb. 1: Felix Mottl um 1900. Foto: Max Stufer Kunstverlag. Mona censia. Literaturarchiv und Bibliothek München (Sign. P / a 1129). 1 Frithjof Haas, Der Magier am Dirigentenpult, Karlsruhe 2006. Eine Rezension der Ver- fasserin fndet sich in Musik in Bayern 72 / 73 (2007 / 08), S. 248–254. 157 Clarissa Höschel Mottls aufewahrt werden.2 Mottl hat diese Aufzeichnungen zwar bis kurz vor seinem Tod geführt, doch sind sie nichts weniger als bewusst für die Nachwelt Hinterlassenes. Soweit sie im Original vorliegen, weisen sie einen sehr eigentümlichen Stil auf, denn sie bestehen, vor allem bis zu seiner New- York-Reise (1903), aus mit stichpunktartigen Notizen vollgeschriebenen Ta- schenkalendern, die meist über mehrere Jahre hinweg verwendet wurden. Mottls Schrif ist klein und unleserlich, seine Einträge sind in aller Regel kurz und knapp und bestehen of nur aus einzelnen Worten, die durch Punk- te getrennt sind. -

Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher Lara C

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher Lara C. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, L. C.(2019). Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5248 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher by Lara C. Wilson Bachelor of Music Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 1991 Master of Music Indiana University, 1997 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: E. Jacob Will, Major Professor J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Lynn Kompass, Committee Member Janet Hopkins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Lara C. Wilson, 2019 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my family, David, Dawn and Lennon Hunt, who have given their constant support and unconditional love. To my Mom, Frances Wilson, who has encouraged me through this challenge, among many, always believing in me. Lastly and most importantly, to my husband Andy Hunt, my greatest fan, who believes in me more sometimes than I believe in myself and whose backing has been unwavering. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Richard Wagner in München

Richard Wagner in München MÜNCHNER VERÖFFENTLICHUNGEN ZUR MUSIKGESCHICHTE Begründet von Thrasybulos G. Georgiades Fortgeführt von Theodor Göllner Herausgegeben von Hartmut Schick Band 76 Richard Wagner in München. Bericht über das interdisziplinäre Symposium zum 200. Geburtstag des Komponisten München, 26.–27. April 2013 RICHARD WAGNER IN MÜNCHEN Bericht über das interdisziplinäre Symposium zum 200. Geburtstag des Komponisten München, 26.–27. April 2013 Herausgegeben von Sebastian Bolz und Hartmut Schick Weitere Informationen über den Verlag und sein Programm unter: www.allitera.de Dezember 2015 Allitera Verlag Ein Verlag der Buch&media GmbH, München © 2015 Buch&media GmbH, München © 2015 der Einzelbeiträge bei den AutorInnen Satz und Layout: Sebastian Bolz und Friedrich Wall Printed in Germany · ISBN 978-3-86906-790-2 Inhalt Vorwort ..................................................... 7 Abkürzungen ................................................ 9 Hartmut Schick Zwischen Skandal und Triumph: Richard Wagners Wirken in München ... 11 Ulrich Konrad Münchner G’schichten. Von Isolde, Parsifal und dem Messelesen ......... 37 Katharina Weigand König Ludwig II. – politische und biografische Wirklichkeiten jenseits von Wagner, Kunst und Oper .................................... 47 Jürgen Schläder Wagners Theater und Ludwigs Politik. Die Meistersinger als Instrument kultureller Identifikation ............... 63 Markus Kiesel »Was geht mich alle Baukunst der Welt an!« Wagners Münchener Festspielhausprojekte .......................... 79 Günter -

Vocal Pedagogy As It Relates to Choral Ensembles

Vocal Pedagogy as It Relates to Choral Ensembles Compiled by Dalan M. Guthrie March 2019 0 Introduction Vocal pedagogy is a topic that has been well-defined for centuries. There are comprehensive books, treatises, dissertations and opinions on every facet of technique as it relates to healthy production of voice in the bel-canto style. For most of its existence as a topic, it has been almost completely limited to the individual study of voice as it pertains to the soloist. Vocal pedagogy as it pertains to choral ensembles is a relatively recent topic of study that has only started to be defined in the last 50 or so years. It is the aim of this bibliography to comprehensively represent the corpus of research of vocal pedagogy as it relates to the choral ensemble. This includes helping to define the role of the choral director, voice teacher, and singer in their responsibility in the education of vocal performance in both solo and choral settings. The nature of this research is pedagogical. Because of this, it is difficult to scientifically define a “correct” methodology of teaching voice. However, the teaching of voice has been evolving for centuries and continues to evolve. As we learn more about vocal science, we can apply them to old models and find new techniques to implement them in simple ways. The techniques change and will always change, but the underlying principles are being reinforced as necessary by authority figures on the subject and by those who practice voice. The stereotype that the comparison of solo and choral singing invariably brings is that of the director and the voice teacher continually at odds with one another over the approach to the vocal education of their students at the secondary and collegiate levels. -

The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance. Malcolm Eugene Beauchamp Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Beauchamp, Malcolm Eugene, "The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3474. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3474 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Why Do Singers Sing in the Way They

Why do singers sing in the way they do? Why, for example, is western classical singing so different from pop singing? How is it that Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballe could sing together? These are the kinds of questions which John Potter, a singer of international repute and himself the master of many styles, poses in this fascinating book, which is effectively a history of singing style. He finds the reasons to be primarily ideological rather than specifically musical. His book identifies particular historical 'moments of change' in singing technique and style, and relates these to a three-stage theory of style based on the relationship of singing to text. There is a substantial section on meaning in singing, and a discussion of how the transmission of meaning is enabled or inhibited by different varieties of style or technique. VOCAL AUTHORITY VOCAL AUTHORITY Singing style and ideology JOHN POTTER CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 IRP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1998 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1998 Typeset in Baskerville 11 /12^ pt [ c E] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Potter, John, tenor. -

Die Mythologischen Musikdramen Des Frühen 17. Jahrhunderts: Eine Gattungshistorische Untersuchung

Die mythologischen Musikdramen des frühen 17. Jahrhunderts: eine gattungshistorische Untersuchung Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades des Doctor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) am Fachbereich Philosophie und Geisteswissenschaften der Freie Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Alessandra Origgi Berlin 2018 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Bernhard Huss (Freie Universität Berlin) Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Franz Penzenstadler (Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen) Tag der Disputation: 18.07.2018 Danksagung Mein Dank gilt vor allem meinen beiden Betreuern, Herrn Prof. Dr. Bernhard Huss (Freie Universität Berlin), der mich stets mit seinen Anregungen unterstützt und mir die Möglichkeit gegeben hat, in einem menschlich und intellektuell anregenden Arbeitsbereich zu arbeiten, und Herrn Prof. Dr. Franz Penzenstadler (Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen), der das Promotionsprojekt in meinen Tübinger Jahren angeregt und auch nach meinem Wechsel nach Berlin fachkundig und engagiert begleitet hat. Für mannigfaltige administrative und menschliche Hilfe in all den Berliner Jahren bin ich Kerstin Gesche zu besonderem Dank verpflichtet. Für die fachliche Hilfe und die freundschaftlichen Gespräche danke ich meinen Kolleginnen und Kollegen sowie den Teilnehmenden des von Professor Huss geleiteten Forschungskolloquiums an der Freien Universität Berlin: insbesondere meinen früheren Kolleginnen Maraike Di Domenica und Alice Spinelli, weiterhin Siria De Francesco, Dr. Federico Di Santo, Dr. Maddalena Graziano, Dr. Tatiana Korneeva, Thea Santangelo und Dr. Selene Vatteroni. -

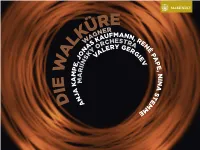

WAGNER / Рихард Вагнер DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (Conclusion) 1 Xii

lk a Waü GN r W , joNas k e e pe kY au r m iNs or f e ri C m i a a Val H k er e a m Y s N a t D j N G r N e , a r a r e G N i e é V p a p e , N i N a s t e e m m 2 Die Walküre Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (conclusion) 1 xii. Schwer wiegt mir der Waffen Wucht / My load of armour weighs heavy on me p18 2’28” DiE WAlkÜRE 2 xiii. Dritte Szene: Raste nun hier, gönne dir Ruh’! / Scene Three: Do stop here, and take a rest p18 8’56” (ThE VAlkyRiE / ВалькиРия) 3 xiv. Wo bist du, Siegmund? / Where are you, Siegmund? p19 3’49” 4 xv. Vierte Szene: Siegmund! Sieh auf mich! / Scene Four: Siegmund, look at me p19 10’55” Siegmund / Зигмунд...................................................................................................................................Jonas KAUFMANN / Йонас Кауфман 5 xvi. Du sahst der Walküre sehrenden Blick / you have seen the Valkyrie’s searing glance p20 4’27” hunding / Хундинг................................. ..............................................................................................Mikhail PETRENKO / михаил ПетренКо 6 xvii. So jung un schön erschimmerst du mir / So young and fair and dazzling you look p20 4’58” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René Pape / рене ПаПе 7 xviii. Funfte Szene: Zauberfest bezähmt ein Schlaf / Scene Five: Deep as a spell sleep subdues p21 3’01” Sieglinde / Зиглинда........................................................................................................................................................Anja