Fidelity to the Event? Lukács' History and Class Consciousness and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Surface and Postmodern Simulation a Retrospective Retrieval

introduction Modern Surface and Postmodern Simulation A Retrospective Retrieval Denn was innen, das ist außen! Johann Wolfgang von Goethe agendas of surface and simulacrum It is in our time that the Enlightenment project has reached its ultimate implosion. In visual terms, the twentieth century of the western hemi- sphere will be remembered as the century in which content yielded to form, text to image, depth to façade, and Sein to Schein. For over a hundred years, mass cultural phenomena have been growing in importance, taking over from elite structures of cultural expression to become sites where real power resides, and dominating ever more surely our social imaginary. As reflections of the processes of capitalist industrialization in forms clad for popular consumption, these manifestations are literal and conceptual expressions of surface:1 they promote external appearance to us in such arenas as architecture, advertising, film, and fashion. Located as we are at the outset of the new millennium, some may recognize with trepidation that mass culture is becoming so wedded to highly orchestrated and intru- sive electronic formats that there seems to be less and less opportunity for any creative maieutics, or participatory “wiggle room.” Modernity’s sur- faces, entirely site-and-street-specific yet mobile and mobilizing, have been replaced by the stasis of the fluid mobility granted to our perception by the technologies of television, the VCR, the World Wide Web, and vir- tual reality.2 Perhaps as a result of this underlying discomfort, we appear to have a case of what Fredric Jameson has called “inverted millenarianism”:3 rather than look forward at future developments, we choose, almost apotropai- 1 2 / Introduction cally, to look back at how mass culture emerged in the first place. -

P. Skalník Authentic Marx and Anthropology: the Dialectic of Lawrence Krader

P. Skalník Authentic Marx and anthropology: the dialectic of Lawrence Krader In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 136 (1980), no: 1, Leiden, 136-147 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 02:16:55PM via free access REVIEW ARTICLE PETER SKALNfK AUTHENTIC MARX AND ANTHROPOLOGY: THE DIALECTIC OF LAWRENCE KRADER The aim of the present review article is to offer an evaluation of Professor Lawrence Krader's three boks on rhe theory of society and history. At the outset I must say that the books under review l have been written by a man of exceptional learning and erudition. L. Krader undoubtedly has contributed toward a better understanding of the principles of hurnan development. He attempts to set up a landmark with his constructive criticism of both Marx' work and the distortions committed in Marx' name by his foliowers, who have self-appointedly called themselves Marxists. Moreover, Krader seems to claim that his theoretica1 work fits int0 rhe context of the praxis of revolutionary change in the world of today and tomorrow. Before presenting the problems taken up by Krader, I shall try to characterize the background to his study of the Marxian and Marxist stream in social history. L. Krader is a well-known figure among an- thropologists. For many years he was the Secretary-Genera1 of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences. Born in New York on December 8, 1919, he studied first under Alfred Tarski at the City College of New York and later at Yale University. -

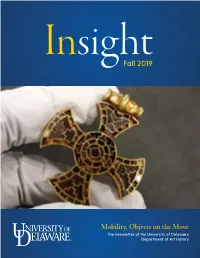

Fall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move

InsightFall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move The newsletter of the University of Delaware Department of Art History Credits Fall 2019 Editor: Kelsey Underwood Design: Kelsey Underwood Visual Resources: Derek Churchill Business Administrator: Linda Magner Insight is produced by the Department of Art History as a service to alumni and friends of the department. Contact Us Sandy Isenstadt, Professor and Chair, Department of Art History Contents E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8105 Derek Churchill, Director, Visual Resources Center E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 From the Chair 4 Commencement 28 Kelsey Underwood, Communications Coordinator From the Editor 5 Graduate Student News 29 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 Around the Department 6 Graduate Student Awards Linda J. Magner, Business Administrator E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8416 Faculty News 11 Graduate Student Notes Lauri Perkins, Administrative Assistant Faculty Notes Alumni Notes 43 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8415 Undergraduate Student News 23 Donors & Friends 50 Please contact us to pose questions or to provide news that may be posted on the department Undergraduate Student Awards How to Donate website, department social media accounts and/ or used in a future issue of Insight. Undergraduate Student Notes Sign up to receive the Department of Art History monthly newsletter via email at ow.ly/ The University of Delaware is an equal opportunity/affirmative action Top image: Old College Hall. (Photo by Kelsey Underwood) TPvg50w3aql. employer and Title IX institution. For the university’s complete non- discrimination statement, please visit www.udel.edu/home/legal- Right image: William Hogarth, “Scholars at a Lecture” (detail), 1736. -

GLOBAL HISTORY and NEW POLYCENTRIC APPROACHES Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History

Foreword by Patrick O’Brien Edited by Manuel Perez Garcia · Lucio De Sousa GLOBAL HISTORY AND NEW POLYCENTRIC APPROACHES Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History Series Editors Manuel Perez Garcia Shanghai Jiao Tong University Shanghai, China Lucio De Sousa Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Tokyo, Japan This series proposes a new geography of Global History research using Asian and Western sources, welcoming quality research and engag- ing outstanding scholarship from China, Europe and the Americas. Promoting academic excellence and critical intellectual analysis, it offers a rich source of global history research in sub-continental areas of Europe, Asia (notably China, Japan and the Philippines) and the Americas and aims to help understand the divergences and convergences between East and West. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15711 Manuel Perez Garcia · Lucio De Sousa Editors Global History and New Polycentric Approaches Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Editors Manuel Perez Garcia Lucio De Sousa Shanghai Jiao Tong University Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Shanghai, China Fuchu, Tokyo, Japan Pablo de Olavide University Seville, Spain Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History ISBN 978-981-10-4052-8 ISBN 978-981-10-4053-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4053-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017937489 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018, corrected publication 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

The Bolshevil{S and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds

The Bolshevil{s and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 into the next century. "Worlds" signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within territorial borders overseas Chinese communities in all countries and regions are also "Chinese worlds". The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and history. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist monographs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Artny Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Gregor Benton Chinese Business in Malaysia Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927 Edmund Terence Gomez Steve Smith Internal and International Migration The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Chinese Perspectives Revolution 1919-1927 Edited by Frank N Pieke and Hein Mallee -

A Thousand Plateaus and Philosophy

Chapter 13 7000 BC: Apparatus of Capture Daniel W. Smith I Te ‘Apparatus of Capture’ plateau expands and alters the theory of the state presented in the third chapter of Anti-Oedipus, while at the same time providing a fnal overview of the sociopolitical philosophy developed throughout Capitalism and Schizophrenia. It develops a series of challeng- ing theses about the state, the frst and most general of which is a thesis against social evolution: the state did not and could not have evolved out of ‘primitive’ hunter-gatherer societies. Te idea that human societies progressively evolve took on perhaps its best-known form in Lewis Henry Morgan’s 1877 book, Ancient Society; Or: Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization (Morgan 1877; Carneiro 2003), which had a profound infuence on nineteenth-century thinkers, especially Marx and Engels. Although the title of the third chap- ter of Anti-Oedipus – ‘Savages, Barbarians, Civilized Men’ – is derived from Morgan’s book, the universal history developed in Capitalism and Schizophrenia is directed against conceptions of linear (or even multilinear) social evolution. Deleuze and Guattari are not denying social change, but they are arguing that we cannot understand social change unless we see it as taking place within a feld of coexistence. Deleuze and Guattari’s second thesis is a correlate of the frst: if the state does not evolve from other social formations, it is because it creates its own conditions (ATP 446). Deleuze and Guattari’s theory of the state begins with a consideration of the nature of ancient despotic states, such as Egypt or Babylon. -

Martin Jay – Habermas and Postmodernism

218 / JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LITERATURE AND AESTHETICS HABERMAS AND POSTMODERNISM / 219 Whether or not his more recent works signification of detour, temporalizing delay; will dispel this caricature remains to be seen. ‘deferring.”4 Differentiation, in other words, FROM THE ARCHIVES From all reports of the mixed reception he implies for Derrida either nostalgia for a lost received in Paris when he gave the lectures unity or conversely a utopian hope for a that became Die philosophische Diskurs der future one. Additionally, the concept is Moderne, the odds are not very high that a suspect for deconstruction because it implies more nuanced comprehension of his work the crystallization of hard and fast will prevail, at least among certain critics. distinctions between spheres, and thus fails Habermas and Postmodernism At a time when virtually any defence of to register the supplementary rationalism is turned into a brief for the interpenetrability of all subsystems, the automatic suppression of otherness, effaced trace of alterity in their apparent heterogeneity and non-identity, it is hard to homogeneity, and the subversive absence predict a widely sympathetic hearing for his undermining their alleged fullness or complicated argument. Still, if such an presence. outcome is to be made at all possible, the Now, although deconstruction ought not Martin Jay task of unpacking his critique of to be uncritically equated with postmodernism and nuanced defence of postmodernism, a term Derrida himself has modernity must be forcefully pursued. One never embraced, one can easily observe that n the burgeoning debate over the out-dated liberal, enlightenment way to start this process is to focus on a the postmodernist temper finds différance apparent arrival of the postmodern rationalism. -

Department of History

———— UC BERKELEY ———— DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY winter 2016 newsletter 1 CONTENTS Chair's Letter, 4 Department News, 6 Faculty Updates, 8 In Memoriam, 13 Faculty Book Reviews, 14 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY University of California, Berkeley 3229 Dwinelle Hall, MC 2550 Berkeley, CA 94720-2550 Phone: 510-642-1971 Fax: 510-643-5323 Email: [email protected] Web: history.berkeley.edu Like Berkeley History on Facebook! Facebook.com/UCBerkeleyHistory Cover images courtesy of UC Berkeley Public Affairs Photo by Daniel Parks SUPPORT THE FUTURE OF HISTORY Donor support plays a critical role in the ways we are able to sustain and enhance the teaching and research mission of the department. Friends of Cal funds are utilized throughout the year in the following ways: • Travel grants for undergraduates researching the material for their senior thesis project • Summer grants (for travel or language study) for graduate students • Dissertation write-up grants for PhD candidates • Conference travel for graduate students who are presenting papers or participating in job interviews • Prizes for the best dissertation and undergraduate thesis • Equipment for the graduate computer lab • Workstudy positions that provide instructional support • Graduate space coordinator position Most importantly, Friends of Cal funds allow the department to direct funding to students in any field of study, so that the money can be directed where it is most needed. This unrestricted funding has enabled us to enhance our multi-year funding package so that we can continue to focus on maintaining the quality that is defined by a Berkeley degree. To support the Department of History, please donate online at give.berkeley.edu or mail checks payable to UC Berkeley Foundation to the address listed on the previous page. -

Neil Smith, 1954-2012: Radical Geography, Marxist Geographer, Revolutionary Geographer

1 Neil Smith, 1954-2012: Radical Geography, Marxist Geographer, Revolutionary Geographer Don Mitchell Department of Geography, Syracuse University and Advanced Research Collaborative, Graduate Center City University of New York September 29, 2013 "Although we found it easy to be brilliant, we always found it confusing to be good." Salman Rushdie, Midnight's Children (quotation found pinned to the bulletin board in Neil Smith’s study when passed away) Neil Smith hated hagiography. He would rail against it in his history and theory of geography seminars at Rutgers University in the early 1990s, holding up what he thought were particularly egregious examples: obituaries published in the Annals. Hagiography for Neil was the antithesis of what our disciplinary history ought to be: it was uncritical and celebratory, when what were needed were hard-nosed engagements with ideas, with real histories that understood ideas as the product of struggle and error as well as genius and insight. Even worse, hagiography extracted its subject from history, setting him (usually him) apart from the world as a lone genius rather than fully ensconcing him in messy social (and personal) practices, situating ideas within the social (and personal) histories from which they emerged. Hagiography had little room to show how what was genius in someone’s ideas might be inextricably linked to, indeed very much a function of both social context and what was flawed or less savory in that person. Hagiography denies that ideas are embodied. Neil’s ideas were embodied. 2 Indeed, David Harvey calls Neil “the perfect practicing Marxist – completely defined by his contradictions.”1 Born in Leith, the old port of Edinburgh, and raised one of four children of a school teaching father and homemaking mother in Dalkeith, a small working-class town to the southeast of the city, Neil had an indestructible passion for the natural world, starting with his native Midlothian landscape and quickly spiraling out, for birdwatching, and for gardening, and he became geography’s preeminent urban theorist. -

Theodor W. Adorno - Essays on Music

Theodor W. Adorno - Essays on Music Selected, with Introduction, Commentary, and Notes by Richard Leppert. Translations by Susan H. Gillespie and others Contents Preface and Acknowledgments Translator's Note Abbreviations Introduction by Richard Leppert 1. LOCATING MUSIC: SOCIETY, MODERNITY, AND THE NEW Commentary by Richard Leppert Music, Language, and Composition (1956) Why Is the New Art So Hard to Understand? (1931) On the Contemporary Relationship of Philosophy and Music (1953) On the Problem of Musical Analysis The Aging of the New Music (1955) The Dialectical Composer (1934) 2. CULTURE, TECHNOLOGY, AND LISTENING Commentary by Richard Leppert The Radio Symphony (1941) The Curves of the Neddle (1927/1965) The Form of the Phonograph Record Opera and the Long-Playing Record (1969) On the Fetish-Character in Music and the Regression of Listening (1938) Little Heresy (1965) 3. MUSIC AND MASS CULTURE Commentary by Richard Leppert What National Socialism Has Done to the Arts (1945) On the Social Situation of Music (1932) On Popular Music [With the assistance of George Simpson] (1941) On Jazz (1936) Farewell to Jazz (1933) Kitsch (c. 1932) Music in the Background (c. 1934) 4. COMPOSITION, COMPOSERS, AND WORKS Commentary by Richard Leppert Late Style in Beethoven (1937) Alienated Masterpiece: The Missa Solemnis (1959) Wagner's Relevance for Today (1963) Mahler Today (1930) Marginalia on Mahler (1936) The Opera Wozzeck (1929) Toward an Understanding of Schoenberg (1955/1967) Difficulties (1964, 1966) Bibliography Introduction Richard Leppert Life and Works Adorno was a genius; I say that without reservation. [He] had a presence of mind, a spontaneity of thought, a power of formulation that I have never seen before or since. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the Red Star State

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Red Star State: State-Capitalism, Socialism, and Black Internationalism in Ghana, 1957-1966 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Kwadwo Osei-Opare © Copyright by Kwadwo Osei-Opare The Red Star State: State-Capitalism, Socialism, and Black Internationalism in Ghana, 1957-1966 by Kwadwo Osei-Opare Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Andrew Apter, Chair The Red Star State charts a new history of global capitalism and socialism in relation to Ghana and Ghana’s first postcolonial leader, Kwame Nkrumah. By tracing how Soviet connections shaped Ghana’s post-colonial economic ideologies, its Pan-African program, and its modalities of citizenship, this dissertation contradicts literature that portrays African leaders as misguided political-economic theorists, ideologically inconsistent, or ignorant Marxist-Leninists. Rather, I argue that Nkrumah and Ghana’s postcolonial government actively formed new political economic ideologies by drawing from Lenin’s state-capitalist framework and the Soviet Economic Policy (NEP) to reconcile capitalist policies under a decolonial socialist umbrella. Moreover, I investigate how ordinary Africans—the working poor, party members, local and cabinet-level government officials, economic planners, and the informal sector—grappled with ii and reshaped the state’s role and duty to its citizens, conceptions of race, Ghana’s place within the Cold War, state-capitalism, and the functions of state-corporations. Consequently, The Red Star State attends both to the intricacies of local politics while tracing how global ideas and conceptions of socialism, citizenship, governmentality, capitalism, and decolonization impacted the first independent sub-Saharan African state. -

Walt Whitman

CONSTRUCTING THE GERMAN WALT WHITMAN CONSTRUCTING THE GERMAN Walt Whitman BY WALTER GRUNZWEIG UNIVERSITY OF IOWA PRESS 1!11 IOWA CITY University oflowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 1995 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gri.inzweig, Walter. Constructing the German Walt Whitman I by Walter Gri.inzweig. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-87745-481-7 (cloth), ISBN 0-87745-482-5 (paper) 1. Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892-Appreciation-Europe, German-speaking. 2. Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892- Criticism and interpretation-History. 3. Criticism Europe, German-speaking-History. I. Title. PS3238.G78 1994 94-30024 8n' .3-dc2o CIP 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 c 5 4 3 2 1 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 p 5 4 3 2 1 To my brother WERNER, another Whitmanite CONTENTS Acknowledgments, ix Abbreviations, xi Introduction, 1 TRANSLATIONS 1. Ferdinand Freiligrath, Adolf Strodtmann, and Ernst Otto Hopp, 11 2. Karl Knortz and Thomas William Rolleston, 20 3· Johannes Schlaf, 32 4· Karl Federn and Wilhelm Scholermann, 43 5· Franz Blei, 50 6. Gustav Landauer, 52 7· Max Hayek, 57 8. Hans Reisiger, 63 9. Translations after World War II, 69 CREATIVE RECEPTION 10. Whitman in German Literature, 77 11.