Final Report Case Study Alpine.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alpine Sites and the UNESCO World Heritage Background Study

Alpine Convention WG UNESCO World Heritage Background study Alpine Sites and the UNESCO World Heritage Background Study 15 August 2014 Alpine Convention WG UNESCO World Heritage Background study Executive Summary The UNESCO World Heritage Committee encouraged the States Parties to harmonize their Tentative Lists of potential World Heritage Sites at the regional and thematic level. Consequently, the UNESCO World Heritage Working Group of the Alpine Convention was mandated by the Ministers to contribute to the harmo- nization of the National Tentative Lists with the objective to increase the potential of success for Alpine sites and to improve the representation of the Alps on the World Heritage List. This Working Group mainly focuses on transboundary and serial transnational sites and represents an example of fruitful collaboration between two international conventions. This background study aims at collecting and updating the existing analyses on the feasibility of poten- tial transboundary and serial transnational nominations. Its main findings can be summarized in the following manner: - Optimal forum. The Alpine Convention is the optimal forum to support the harmonisation of the Tentative Lists and subsequently to facilitate Alpine nominations to the World Heritage List. - Well documented. The Alpine Heritage is well documented throughout existing contributions in particular from UNESCO, UNEP/WCMC, IUCN, ICOMOS, ALPARC and EURAC. The contents of these materials are synthesized, updated and presented in the present study. - Official sources. Only official sources, made publicly available by the UNESCO World Heritage Cen- tre, were used in this study. The Tentative Lists are not always completely updated or comparable and some entries await to be completed or revised. -

EU Strategy for the Alpine Region

BRIEFING EU strategy for the Alpine region SUMMARY Launched in January 2016, the European Union strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) is the fourth and most recent macro-regional strategy to be set up by the European Union. One of the biggest challenges facing the seven countries and 48 regions involved in the EUSALP is that of securing sustainable development in the macro-region, especially in its resource-rich, but highly vulnerable core mountain area. The Alps are home to a vast array of animal and plant species and constitute a major water reservoir for Europe. At the same time, they are one of Europe's prime tourist destinations, and are crossed by busy European transport routes. Both tourism and transport play a key role in climate change, which is putting Alpine natural resources at risk. The European Parliament considers that the experience of the EUSALP to date proves that the macro-regional concept can be successfully applied to more developed regions. The Alpine strategy provides a good example of a template strategy for territorial cohesion; as it simultaneously incorporates productive areas, mountainous and rural areas, and some of the most important and highly developed cities in the EU. Although there is a marked gap between urban and rural mountainous areas, the macro-region shows a high level of socio-economic interdependence, confirmed by recent research. Disparities (in terms of funding and capacity) between participating countries, a feature that has caused challenges for other EU macro-regional strategies, are less of an issue in the Alpine region, but improvements are needed and efforts should be made in view of the new 2021-2027 programming period. -

21998A0207(01) Official Journal L 033 , 07/02/1998 P. 0022

21998A0207(01) Protocol of Accession of the Principality of Monaco to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps Official Journal L 033 , 07/02/1998 p. 0022 - 0024 Dates: OF DOCUMENT: 20/12/1994 OF EFFECT: 00/00/0000; ENTRY INTO FORCE SEE ART 4.2 OF SIGNATURE: 20/12/1994; Chambry OF END OF VALIDITY: 99/99/9999 Authentic language: FRENCH ; GERMAN ; ITALIAN ; SLOVENIAN Author: FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY ; SPAIN ; AUSTRIA ; FRANCE ; ITALY ; LIECHTENSTEIN ; SLOVENIA ; SWITZERLAND ; EUROPEAN COMMUNITY ; MONACO Subject matter: EXTERNAL RELATIONS ; ENVIRONMENT Directory code: 11306000 ; 15102000 EUROVOC descriptor: action programme ; cross-border cooperation ; environmental protection ; international convention ; Alpine Region ; Monaco Legal basis: 192E130S-P1............... ADOPTION 192E228-P2................ ADOPTION 192E228-P3L1.............. ADOPTION pd4ml evaluation copy. visit http://pd4ml.com Amendment to: 296A0312(01)......AMENDMENT..... COMPLETION TEXT FR DAT.ENT.FORCE 296A0312(01)......AMENDMENT..... COMPLETION ANN FR DAT.ENT.FORCE Amended by: ADOPTED-BY.... 398D0118.......... FR 16/12/97 PROTOCOL OF ACCESSION of the Principality of Monaco to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY, THE ITALIAN REPUBLIC, THE PRINCIPALITY OF LIECHTENSTEIN, THE REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA, THE SWISS CONFEDERATION, THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY, Signatories to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps (Alpine Convention),on the one hand,and THE PRINCIPALITY OF MONACO,on the other, WHEREAS the Principality of Monaco has requested to become a Contracting Party to the Alpine Convention, IN THEIR DESIRE to ensure the protection of the Alps throughout theentire Alpine area, HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS: Article 1 pd4ml evaluation copy. -

Towards More Resilient Economies in Alpine Regions Riccardo Brozzi, Lucija Lapuh, Janez Nared, Thomas Streifeneder D E R a N

Acta geographica Slovenica, 55-2, 2015, 339–350 towaRds MoRe Resilient eConoMies in alPine Regions Riccardo Brozzi, Lucija Lapuh, Janez Nared, Thomas Streifeneder D E R A N Z E N A J Regional economies are confronted with constant transformation, which is even more radical in times of economic crises. The picture shows the Schiffbau – the premises of former shipbuilding company in Zurich that were transformed into theatre. Riccardo Brozzi, Lucija Lapuh, Janez Nared, Thomas Streifeneder, Towards more resilient economies in Alpine regions Towards more resilient economies in Alpine regions DOI: http: //dx.doi.org/10.3986/AGS.916 UDC: 911.3:338.124.4(234.3) COBISS: 1.01 ABSTRACT: The economic crisis the world has faced since 2007 has had devastating effects on many regions to various degrees. How regions respond to economic shock depends on regional economic structure and performance, administrative capacity, resources, human capital, social capital, and other factors, and is per - ceived as resilience: the ability of a regional economy to withstand, absorb, or overcome an external economic stress. Because one of the future strategic goals for the Alpine Space Programme area is fostering its resilience, we studied the performance of Alpine regions in the pre - and post -crisis period in order to assess the effects of the economic crisis and to provide basic directions on how to make the Alps more resilient in the future . The results have revealed differences among three selected groups of regions as well as some country -spe - cific characteristics of the regional response that can generally be seen in the weaker performance of some Italian and Slovenian regions. -

EU Strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) ITALIAN PRESIDENCY

February 2019 EU Strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) ITALIAN PRESIDENCY 2019 Work Programme 1. Introduction: The Alpine Region1 The Alpine Region is among the largest natural, economic and productive areas in Europe, with over 80 million inhabitants, and among the most attractive tourist regions, welcoming millions of guests per year. While trade, businesses and industry in the Alpine Region are concentrated in the main areas of settlement on the outskirts of the Alps and in the large Alpine valleys along the major traffic routes, over 40 % of the Region is not or not permanently inhabited. Due to the Alpine Region’s unique geographic and natural characteristics, it is particularly affected by several of the challenges arising in the 21st century: Economic globalisation requires sustainable and continuously high competitiveness as well as the capacity to innovate; Demographic change leads to an ageing population and outward migration of highly qualified labour; Global climate change already has noticeable effects on the environment, biodiversity and living conditions for the inhabitants of the Alpine Region; A reliable and sustainable energy supply must be ensured in the parts of the Region which are difficult to access; As a transit region in the heart of Europe and due to its geographic features, the Alpine Region requires sustainable and custom-fit traffic concepts; The Alpine Region is to be preserved as a unique natural and cultural environment. 1 This description part comes from the Bavarian 2017 Work Programme 1 February 2019 The different characteristics of peripheral areas, centers of different sizes, and metropolises, require a dialogue on a basis of equality and the development of an alliance aimed at sustainable development while respecting its needs. -

Mapping the Alps

Mapping the Alps Mapping the Alps Axel Borsdorf, Ulrike Tappeiner & Erich Tasser Electoral turnout in local elections (Tappeiner et al. 2008: 138). Introduction the demographic, economic and social structures? These issues have motivated the authors to create a set of maps At first glance it seems an easy task to create an atlas that would answer such questions and encourage read- of the Alps. From their school days everybody remem- ers to study the enormous structural differences and the bers the map of the alpine countries as found in any rapid spatial and social changes that affect the Alps in Central European school atlas. Take a closer look and particular. you begin to wonder: where exactly do the Alps begin? Nearly twenty years ago, the Alpine Convention Where do they end? Does orography provide sufficient started on the task of creating a monitoring and in- information on the spatial structure of the Alps? Are the formation system for the Alps, but because of political Alps static or do they not rather experience a variety of and data-technical problems this task has not been sat- changes in the nature of the land, the cultural landscape, isfactorily completed to date. One of the most serious 186 Axel Borsdorf, Ulrike Tappeiner & Erich Tasser problems was the harmonization of data that have been resources, but they also expose the hillsides and valleys defined in a variety of ways in the official statistics of to various dangers. individual Alpine states and moreover may have been The population in the Alps does not only face natu- gathered at different points in time. -

BHL-Europe Promotion Kit

D5.6 ECP-2008-DILI-518001 BHL-Europe BHL-Europe promotion kit Deliverable number D5.6 Dissemination level Public Delivery date 5 November 2009 Status Final Author(s) Jiří Kvaček eContentplus This project is funded under the eContentplus programme1, a multiannual Community programme to make digital content in Europe more accessible, usable and exploitable. 1 OJ L 79, 24.3.2005, p. 1. 1/5 5 November 2009 D5.6 0 Document History 0.1 Contributors Person Partner Jiří Kvaček NMP Pavel Douša NMP Henning Scholz MfN 0.2 Revision History Revision Date Author Version Change Reference & Summary 12 October 2009 Jiří Kvaček 0.1 Initial draft of D5.6 3 November 2009 Jiří Kvaček 0.2 Revision based on CWG comments 4 November 2009 Jiří Kvaček 0.3 Revision based on comments by H. Scholz 5 November 2009 Jiří Kvaček 1.0 Final version 0.3 Reviewers and Approvals This document requires the following reviews and approvals. Name Position Signature on approval Date Version Henning Scholz BHL-Europe PCO 5 November 2009 1.0 0.4 Distribution This document has been distributed to: Group Date of issue Version CWG 12 October 2009 0.1 BHL-Europe consortium 29 October 2009 0.1 BHL-Europe consortium 12 November 2009 1.0 2/5 5 November 2009 D5.6 Table of contents 0 DOCUMENT HISTORY...................................................................................................................................2 0.1 Contributors .......................................................................................................................................2 0.2 Revision -

ESPON-TITAN Case Studies Report Alpineregion

CASE STUDY REPORT // ESPON-TITAN Territorial Impacts of Natural Disasters Alpine Region Applied Research // June 2021 This ESPON-TITAN is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States, the United Kingdom and the Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinions of members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Coordination: Carolina Cantergiani, Efren Feliu, TECNALIA Research & Innovation, Spain Authors Mark Fleischhauer, Polina Mihal, Maren Blecking, Pauline Fehrmann, Stefan Greiving Advisory group Project Support Team: Adriana May, Lombardy Region (Italy), Marcia Van Der Vlugt, Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, Spatial Development Directorate (the Netherlands) ESPON EGTC: Zintis Hermansons (Project Expert), Caroline Clause (Financial Expert) Acknowledgements This case study was supported by interviews with and feedback from the following regional stakeholders whom we would like to thank for their cooperation: Blanka Bartol (Ministrstvo za okolje in proctor, Direktorat za prostor, graditev in stanovanja, Slovenia; Member of the Slovenian delegation in the Permanent Committee of the Alpine Convention), Kilian Heil (Bundesministerium für Landwirtschaft, Regionen und Tourismus, Sektion III – Forstwirtschaft und Nachhaltigkeit, Abteilung III/4 – Wildbach- und Lawinenverbauung und Schutzwaldpolitik, Austria; Member of the EUSALP Action Group 8; Member of the Natural Hazards Platform (PLANALP) of the Alpine Convention), Jože Papež (Hidrotehnik Vodnogospodarsko podjetje d.o.o., Slovenia; Member of the Natural Hazards Platform (PLANALP) of the Alpine Convention; Member of the EUSALP Action Group 8), Dr. -

The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-09-16 The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices Benjamin, Mary Wilder Benjamin, M. W. (2014). The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28251 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1767 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices by Mary Wilder Benjamin A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2014 © Mary Wilder Benjamin 2014 Abstract Recreational mountaineering is a complex pursuit that continues to evolve with respect to demographics, participant numbers, methods, equipment, and the nature of the experience sought. The activity often occurs in protected areas where agency managers are charged with the inherently conflicting mandate of protecting the natural environment and facilitating high quality recreational experiences. Effective management of such mountaineering environs is predicated on meaningful understanding of the users’ motivations, expectations and behaviours. -

Analysis of Mountain Areas in EU Member States, Acceding and Other European Countries

Mountain Areas in Europe – Final Report 8. Mountain policies in Europe This chapter includes an overview and analyses of policies affecting the mountain areas of the countries considered in the report. In addition to information available from various European sources, this chapter and the next are derived from national- level information and SWOT analyses for the mountains of each country provided in the national reports. These were based on the synthesis and analysis of available information, and interviews with a total of 111 mountain actors (policy makers, representatives of professional organisations, elected people, researchers, Annex 2)1. The interviews utilised a questionnaire with closed and semi-open questions. In addition, European and supra-national organisations concerned with mountain issues were contacted with a similar set of questions as covered in the interviews. A wide range of public interventions is available to support development in European mountain areas. These interventions vary considerably, according not only to the importance and the diversity of these areas, but also to the institutional setting of each country (centralised, federal, EU Member States, acceding countries, others, etc.) – which is undergoing rapid change in most of the acceding and candidate countries, particularly with regard to integration. 8.1. National policies and instruments For the purposes of analysis, we address ‘mountain policies’ in the widest sense, including: • general measures and policies with a territorial impact relevant for some mountain issues (e.g., planning); • sectoral policies which have a particular effect on the development of mountain areas (e.g., agriculture, tourism policy); • relevant actions or programmes involving mountain zones (e.g., Interreg); • explicit measures and policies directed at mountain areas in order to meet their particular needs; • explicit integrated mountain policies. -

* Council of * Conseil De L'

Naturona * COUNCIL OF * CONSEIL DE L’ Naturopa N°72-1993 : : Editorial V. Bossevski 3 What future for our mountains? W. Bätzing 4 Managing this vulnerable environment P. Messerli 6 The Rhodope Mountains. Jewel of Bulgaria J. Danchev 8 * * * Mountainous perspectives. Lessons from history E. Lichtenberger 9 CENTRE An ecological approach P. Stoll 11 NATUROPA Living nature P. Ozenda 12 The Alpine Convention U. Tödter 14 In Italy F. Bartaletti 15 A blessing in disguise? A. Gosar 20 Editorial Teberda A.M. Amirkhanov, N. N. Polivanova 22 he Balkans represent a vast mountai and species endemic to the Balkans such as altitude run to 2,000 m. There are between nous universe with a natural environ the Pinus peuce. Coniferous bushes and 1,700 and 1,850 higher plant species and Delights in the heights H. Haid 23 T ment very similar to that of the Alps, Siberian junipers grow above the forests, between 170 and 200 species of vertebrates. the Appenines and the Carpathians, but with rocky Alpine meadows dotted with small Out of the 50 protected areas in Bulgaria on Naturopa is published in English, Wise use of natural resources F. Sieren, P. F. Sieben 24 which also has its own special features. The glaciers at the summits and peaks. the United Nations’ list of national parks, 40 French, German, Italian, Spanish and proximity of Asia has enriched its fauna and are in the mountains. Portuguese by the Centre Naturopa of the Mountaineering: protection first J. Klenner 26 flora, but it is the species and populations Mountain conservation in Bulgaria dates Council of Éurope, F-67075 Strasbourg typical of the Balkans alone that make it from the last century. -

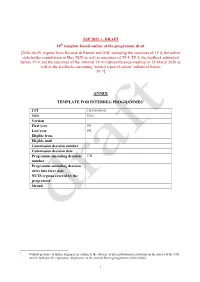

ASP 2021 +: DRAFT 10 Template Based Outline of the Programme Draft [2020-06-29, Experts from Rosinak & Partner and OIR; Incl

ASP 2021 +: DRAFT 10th template based outline of the programme draft [2020-06-29, experts from Rosinak & Partner and OIR; including the outcomes of TF 8, the online stakeholder consultation in May 2020 as well as outcomes of TF 4, TF 5, the feedback submitted before TF-6 and the outcomes of the informal TF-6 videoconference-meeting on 26 March 2020 as well as the feedback concerning “related types of action” submitted before TF 7] ANNEX TEMPLATE FOR INTERREG PROGRAMMES1 CCI [15 characters] Title [255] Version First year [4] Last year [4] Eligible from Eligible until Commission decision number Commission decision date Programme amending decision [20] number Programme amending decision entry into force date NUTS regions covered by the programme Strand 1 Without prejudice to further alignment in relation to the outcome of interinstitutional negotiations on the articles of the CPR and the fund-specific regulations. Alignments on the external Interreg programmes still to follow. 1 1. Programme strategy: main development challenges and policy responses 1.1. Programme area (not required for Interreg C programmes) Reference: Article 17(4)(a), Article 17(9)(a) Text field [2 000] Status from TF-meeting 8: The program area for the Alpine Space Programme 2021-2027 preliminary comprises the following territories: Austria: the whole territory France – NUTS 2: Alsace*, Franche-Comté, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, Rhône-Alpes Germany – NUTS 2: Oberbayern, Niederbayern**, Oberpfalz**, Oberfranken**, Mittelfranken**, Unterfranken**, Schwaben; Stuttgart**, Karlsruhe**, Freiburg, Tübingen Italy – NUTS 2: Lombardia, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Veneto, Provincia Autonoma di Trento, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano / Bozen, Valle d‘Aosta / Vallée d'Aoste, Piemonte, Liguria Liechtenstein: the whole territory Slovenia: the whole territory Switzerland: the whole territory.