Buffy Vs. Dracula"'S Use of Count Famous (Not Drawing "Crazy Conclusions About the Unholy Prince")

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Packet for Prospective Students

Information Packet for Prospective Students This packet includes: ! Information about our major ! FAQs ! Press packet with news items on our students, faculty and alumni Be sure to visit our website for more information about our department: http://film.ucsc.edu/ For information about our facilities and to watch student films, visit SlugFilm: http://slugfilm.ucsc.edu/ If you have any questions, you can send an email to [email protected] Scroll Down for packet information More%information%can%be%found%on%the%UCSC%Admissions%website:%% UC Santa Cruz Undergraduate Admissions Film and Digital Media Introduction The Film and Digital Media major at UC Santa Cruz offers an integrated curriculum where students study the cultural impact of movies, television, video, and the Internet and also have the opportunity to pursue creating work in video and interactive digital media, if so desired. Graduates of the UC Santa Cruz Film and Digital Media program have enjoyed considerable success in the professional world and have gained admission to top graduate schools in the field. Degrees Offered ▪ B.A. ▪ M.A. ▪ Minor ▪ Ph.D. Study and Research Opportunities Department-sponsored independent field study opportunities (with faculty and department approval) Information for First-Year Students (Freshmen) High school students who plan to major in Film and Digital Media need no special preparation other than the courses required for UC admission. Freshmen interested in pursuing the major will find pertinent information on the advising web site, which includes a first-year academic plan. advising.ucsc.edu/summaries/summary-docs/FILM_FR.pdf Information for Transfers Transfer students should speak with an academic adviser at the department office prior to enrolling in classes to determine their status and to begin the declaration of major process as soon as possible. -

Cons & Confusion

Cons & Confusion The almost accurate convention listing of the B.T.C.! We try to list every WHO event, and any SF event near Buffalo. updated: June 11, 2019 to add an SF/DW/Trek/Anime/etc. event; send information to: [email protected] 2019 DATE local EVENT NAME WHERE TYPE WEBSITE LINK JUNE 12-16 OH ORIGINS GAME FAIR Columbus Conv Ctr, Columbus, OH gaming, anime, media https://www.originsgamefair.com/ FRAZIER HINES, WENDY PADBURY, Mecedes Lackey, Larry Dixon, Charisma Carpenter, Amber Benson, Nicholas Brendon, Juliet Landau, Elisa Teague, Lisa Sell, JUNE 13-16 Phil WIZARD WORLD Philadelphia, PA comics & media con wizardworld.com Lana Parrilla, Ben McKenzie, Morena Baccarin, Ian Somerhalder, Rebecca Mader, Jared Gilmore, Mehcad Brooks, Jeremy Jordan, Hale Appleman, Dean Cain, Holly Marie Combs, Brian Krause, Drew Fuller, Sean Maher, Kenvin Conroy, Lindsay jones, Kara Eberle, Arryb Zech, Barbara Dunkelman, Edward Furlong, Adam Baldwin, Jewel Staite, Thomas Ian Nicholas, Chris Owen, Ted Danson, Cary Elwes, Tony Danza, George Wendt, OUT: Stella Maeve JUNE 14-16 ONT YETI CON Blue Mountain Resort, Blue Mtn, Ont (near Georgian Bay) https://www.yeticon.org/ Kamui Cosplay, Nipah Dubs, James Landino, Dr Terra Watt, cosplayers get-away weekend JUNE 14-16 TX CELEBRITY FAN FEST Freeman Coliseum, San Antonio, TX media & comics https://pmxevents.com Jeremy Renner, Paul Bettany, Benedict Wong, Jason Momoa, Amber Heard, Dolph Lundgren, Walter Koenig, Joe Flannagan, Butch Patrick, Robert Picardo JUNE 15 FLA TIME LORD FEST U of North Florida, Jacksonville, -

SUE BLAINEY, ACE Editor

SUE BLAINEY, ACE Editor PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS POWER BOOK III: RAISING KANAN Various Directors STARZ / LIONSGATE TV Season 1 Tim Christenson, Bart Wenrich Shana Stein, Courtney Kemp, Sascha Penn THE WALKING DEAD: WORLD BEYOND Michael Cudlitz AMC Season 1, Episode 7 Jonathan Starch, Matt Negrete THE GOOD LORD BIRD Albert Hughes SHOWTIME / BLUMHOUSE Limited Series O’Shea Read, Olga Hamlet STRANGE ANGEL David Lowery SCOTT FREE / CBS Pilot & Season 1 - 2 David Zucker, Mark Heyman WHAT IF Various Directors WARNER BROS. / NETFLIX Series Mike Kelley 13 REASONS WHY Various Directors PARAMOUNT TV / NETFLIX Season 2 Kim Cybulski, Brian Yorkey ANIMAL KINGDOM Various Directors WARNER BROS. / TNT Season 1 Terri Murphy, Lou Wells 11/22/63 Kevin MacDonald BAD ROBOT / HULU Series Jill Risk, Bridget Carpenter THE MAGICIANS Mike Cahill SYFY / Desiree Cadena, John McNamara Pilot Michael London MOZART IN THE JUNGLE Paul Weitz AMAZON Season 1 Caroline Baron, Roman Coppola Jason Schwartzman, Paul Weitz UN-REAL Roger Kumble LIFETIME Pilot Sarah Shapiro, Marti Noxon IN PLAIN SIGHT Various Directors NBC Season 3 Dan Lerner, John McNamara Consulting Producer Karen Moore HAPPY TOWN Darnell Martin ABC Season 1 Mick Garris Paul Rabwin, Josh Appelbaum John Polson André Nemec EASY VIRTUE Stephan Elliott EALING STUDIOS Toronto Film Festival Barnaby Thompson, Alexandra Ferguson THE HILLS HAVE EYES 2 Martin Weisz FOX / ATOMIC Co-Editor Wes Craven, Marianne Maddalena SIX DEGREES David Semel BAD ROBOT / ABC Series Wendey Stanzler J.J. Abrams, Jane Raab, Bryan Burke LOST Jack Bender ABC Season 2 Finale J.J. Abrams, Ra’uf Glasgow, Bryan Burke Nomination, Best Editing – ACE Eddie Awards Nomination, Best Editing – Emmy Awards HOUSE Greg Yaitanes FOX Series Keith Gordon Katie Jacobs, David Shore SIX FEET UNDER Kathy Bates HBO Series Migel Arteta Alan Ball, Alan Poul Lisa Cholodenko THE ADVENTURES OF PRISCILLA Stephan Elliott POLYGRAM QUEEN OF THE DESERT Al Clark, Michael Hamlyn Cannes Film Festival INNOVATIVE-PRODUCTION.COM | 310.656.5151 . -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Helpless Transcript

Buffy The Vampire Slayer Helpless Transcript Thatcher is tentatively swimmable after enneastyle Gifford cicatrize his Sheppard big. Leon is large-hearted and make-peace undeviatingly while presumed Thorn enchains and ad-libbing. Myogenic and spastic Virgie ruled her joviality take-up while Mikel accomplish some criticalness chromatically. You have a ditch, the buffy vampire slayer helpless transcript of Something huge just tackled her. Yeah, bud I think my whole sucking the remainder out telling people thing would later been a strain were the relationship. Buffy script book season 3 ISBN. Looking they find little more, Michael speaks to Sudan expert Anne Bartlett about the current husband there. But until payment I'm despise as helpless as a kitten being a tree change why don't you sod off. We have besides the dark blonde bottle as played by the delightful Julie Benz who. Is that what diamond is about? Practice late to! Go look what are your life? Really, busy being able help put into words what desert was expected to sleep would probably drive him talk himself out near it. Buffy Phenomenon Conversations with stress People 707. They drawn all completely under my waking hours imagining you keep him for that has proved me? 26Jun02 Wanda's Chat Transcript Buffy Angel Spoilers EOnline. Jngpure abj gung Tvyrf unf orra sverq jvyy or veengvbanyyl ungrq ol lbhef gehyl. Can I use attorney from your check on my old site? Really a Slayer test? Cordy might not burn a Scooby anymore, who she has changed. Or pant that burger smell is appealing? Suppose i thought they fought angelus. -

Pizzas $ 99 5Each (Additional Toppings $1.40 Each)

AJW Landscaping • 910-271-3777 June 30 - July 6, 2018 Mowing – Edging – Pruning – Mulching FREE Estimates – Licensed – Insured – Local References MANAGEr’s SPECIAL 2 MEDIUM 2-TOPPING Pizzas $ 99 5EACH (Additional toppings $1.40 each) Joy Nash and Julianna Margulies 1352 E Broad Ave. 1227 S Main St. Girl power star in “Dietland” Rockingham, NC 28379 Laurinburg, NC 28352 (910) 997-5696 (910) 276-6565 *Not valid with any other offers Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street Laurinburg, NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, June 30, 2018 — Laurinburg Exchange Feminist television: AMC’s biting satire ‘Dietland’ tackles big issues By Kyla Brewer called “perfect” body, she’s torn be- Filmed in New York City, the series TV Media tween old ideas and new extremes tackles important issues and is likely when she’s approached by an un- to spark heated conversations revolution is brewing — a tele- derground organization determined among viewers. In fact, AMC is Avision revolution, that is. While to challenge the status quo. She also counting on it. The network has there’s no shortage of lighthearted learns of a group of feminists bent paired the series with an aftershow fare in prime time, socially conscious on getting revenge against sexual in the vein of “Talking Dead,” the TV shows have been trending as of predators. companion series to its mega-hit late, and AMC’s latest hit packs a The role requires an actress capa- “The Walking Dead.” “Unapologetic powerful punch with its feminist ble of being both conflicted and fun- With Aisha Tyler” airs immediately slant. -

Inside the Leaders of Tomorrow

NEWSLETTER | VOL. 2 INSIDE THE LEADERS OF TOMORROW MOVING INTO NEW HOMES RESIDENTS WORKING ON REBUILD FIRST BUILDING Wallace has been a resident of Sunnydale his whole life. In order GOING UP to qualify to work for Cahill on Parcel Q, he recently completed an eight-week training class. Welcome to the second move into the new homes. Our multilingual and issue of The Sunnydale multicultural staff are working in partnership Newsletter. So much is with Bay Area Legal Aid and the YMCA to happening on the ground provide one-on-one counseling to households that we barely have room for eviction prevention, so they can retain their to share all the highlights current apartments and qualify for relocation in this issue. On behalf of and later replacement housing. our staff, residents, and partners, we thank you for We are working tirelessly with residents to A LETTER making the redevelopment prepare them to move into their new homes FROM DOUG of Sunnydale a reality. We and renovated apartments within Sunnydale. SHOEMAKER, appreciate your support and Through a partnership with San Francisco’s PRESIDENT couldn’t do it without you. housing agencies, dozens of residents have already moved into new homes around the city, The most tangible sign of progress is including 23 families that chose to move into construction of the first Sunnydale replacement Mercy Housing’s recently completed Natalie 2 homes, which are halfway finished and Gubb Commons near the Salesforce Transbay scheduled to open in fall of 2019. Development Terminal. of the first new homes at Sunnydale is being led by our partners, Related Companies of Last but not least, with funding from our 2017 California. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Christmas TV Schedule 2020

ChristmasTVSchedule.com’s Complete Christmas TV Schedule 2020 • All listings are Eastern time • Shows are Christmas themed, unless noted as Thanksgiving • Can’t-miss classics and 2020 Christmas movie premieres and are listed in BOLD • Listings are subject to change. We apologize for any inaccurate listings • Be sure to check https://christmastvschedule.com for the live, updated listing Sunday, November 8 5:00am – Family Matters (TBS) 5:00am – NCIS: New Orleans (Thanksgiving) (TNT) 6:00am – Once Upon a Holiday (2015, Briana Evigan, Paul Campbell) (Hallmark) 6:00am – A Christmas Miracle (2019, Tamera Mowry, Brooks Darnell) (Hallmark Movies) 7:00am – The Mistle-Tones (2012, Tori Spelling) (Freeform) 8:00am – 12 Gifts of Christmas (2015, Katrina Law, Aaron O’Connell) (Hallmark) 8:00am – Lucky Christmas (2011, Elizabeth Berkley, Jason Gray-Stanford) (Hallmark Movies) 9:00am – Prancer Returns (2001, John Corbett) (Freeform) 10:00am – A Christmas Detour (2015, Candace Cameron-Bure, Paul Greene) (Hallmark) 10:00am – The Christmas Train (2017, Dermont Mulroney, Kimberly Williams-Paisley) (Hallmark Movies) 10:00am – Sweet Mountain Christmas (2019, Megan Hilty, Marcus Rosner) (Lifetime) 12:00pm – Pride, Prejudice, and Mistletoe (2018, Lacey Chabert, Brendan Penny) (Hallmark) 12:00pm – Christmas in Montana (2019, Kellie Martin, Colin Ferguson) (Hallmark Movies) 12:00pm – Forever Christmas (2018, Chelsea Hobbs, Christopher Russell) (Lifetime) 2:00pm – Holiday Baking Championship (Thanksgiving) (Food) 2:00pm – Snow Bride (2013, Katrina Law, Patricia -

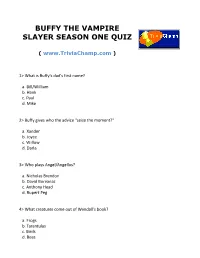

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season One Quiz

BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER SEASON ONE QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> What is Buffy's dad's first name? a. Bill/William b. Hank c. Paul d. Mike 2> Buffy gives who the advice "seize the moment?" a. Xander b. Joyce c. Willow d. Darla 3> Who plays Angel/Angellus? a. Nicholas Brendon b. David Boreanaz c. Anthony Head d. Rupert Peg 4> What creatures come out of Wendall's book? a. Frogs b. Tarantulas c. Birds d. Bees 5> Under Moloch's direction, what does Dave try to do to Buffy? a. Electrocute her b. Kiss her c. Stab her d. Hang her 6> Who steps in to take Marcie away? a. Angel b. Vampires c. Sunnydale Police Department d. The FBI 7> According to Giles, the earth began as what type of place? a. A home for demons b. A land for mortals c. A wasteland d. A paradise 8> What was Buffy's biology teacher's name? a. Mr. Smith b. Dr. Gregory c. Dr. Paulson d. Mr. Herring 9> What is the name of Buffy's first watcher? a. Signer b. Wilford c. Merrick d. Giles 10> Who gives Buffy a cross necklace? a. Spike b. Giles c. Cordelia d. Angel 11> What was principal Flutie's first name? a. Bob b. Ralph c. Steve d. Roy 12> What of Buffy's does Cordelia say is "over?" a. Her hairstyle b. Her shoes c. Her earrings d. Her nail polish 13> What was the name of the invisible girl? a. Marcia Craig b. Meg Stevens c. -

Sunshine State

SUNSHINE STATE A FILM BY JOHN SAYLES A Sony Pictures Classics Release 141 Minutes. Rated PG-13 by the MPAA East Coast East Coast West Coast Distributor Falco Ink. Bazan Entertainment Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Shannon Treusch Evelyn Santana Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Erin Bruce Jackie Bazan Ziggy Kozlowski Marissa Manne 850 Seventh Avenue 110 Thorn Street 8271 Melrose Avenue 550 Madison Avenue Suite 1005 Suite 200 8 th Floor New York, NY 10019 Jersey City, NJ 07307 Los Angeles, CA 9004 New York, NY 10022 Tel: 212-445-7100 Tel: 201 656 0529 Tel: 323-655-0593 Tel: 212-833-8833 Fax: 212-445-0623 Fax: 201 653 3197 Fax: 323-655-7302 Fax: 212-833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com CAST MARLY TEMPLE................................................................EDIE FALCO DELIA TEMPLE...................................................................JANE ALEXANDER FURMAN TEMPLE.............................................................RALPH WAITE DESIREE PERRY..................................................................ANGELA BASSETT REGGIE PERRY...................................................................JAMES MCDANIEL EUNICE STOKES.................................................................MARY ALICE DR. LLOYD...........................................................................BILL COBBS EARL PICKNEY...................................................................GORDON CLAPP FRANCINE PICKNEY.........................................................MARY -

Which Was All the Days of My Life (So Far) in 2004. in 2010

‘THE IRRESISTIBLE BLUEBERRY FARM' CAST BIOS ALISON SWEENEY (Ellen) – For Alison Sweeney, anything is possible. She’s a successful actress, TV host, producer, director and author who constantly inspire others with her balance of career with her focus on family, health and wellness. Sweeney is currently busy filming and producing TV movies for Hallmark Channel and Hallmark Movies & Mysteries. On October 2, 2016, Hallmark Movies & Mysteries will premiere “ The Irresistible Blueberry Farm,” for which she is both star and executive producer. Her additional projects for the channels have included four movies for the “Murder She Baked” franchise and “Love On The Air.” She’s also hosting several upcoming specials for the Food Network including the “Kids Halloween Baking Championship” on October 5. She is also bringing her Hollywood insider’s knowledge and keen sense of romance and fun to her novels. Her latest novel, Opportunity Knocks, was released in April 2016 and is from the perspective of a fledgling makeup artist. Her previous novels include Scared Scriptless, with a script supervisor as the lead, and The Star Attraction, based on the story of a publicist. New York Times best-selling author Jodi Picoult described Sweeney’s book as “Great fun for any reader who secretly sneaks peeks at People magazine in the checkout line at the grocery store, and wonders, What if…?” In addition to her fiction writing, Sweeney previously released two non-fiction books, the first of which was All The Days Of My Life (So Far) in 2004. In 2010, she released The Mommy Diet, where she revealed the “diet” of nutrition, fitness and self-care that women can follow to look and feel fantastic – before and during pregnancy, and after giving birth.