Divination and Interpretation of Signs in the Ancient World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossolalia: Divine Speech Or Man-Made Language? a Psychological Analysis of the Gift of Speaking in Tongues in the Pentecostal Churches in Botswana

GLOSSOLALIA: DIVINE SPEECH OR MAN-MADE LANGUAGE? A PSYCHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE GIFT OF SPEAKING IN TONGUES IN THE PENTECOSTAL CHURCHES IN BOTswaNA James N Amanze and Tino Shanduka Department of Theology and Religious Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Botswana [email protected] ABSTRACT Glossolalia is a very important element in the life of Pentecostal Churches and is at the centre of their spirituality. This paper examines the gift of speaking in tongues from a psychological perspective in order to find out what psychologists say about this very important gift of the Holy Spirit. The paper begins by looking at the history of speaking in tongues in the Church from the day of Pentecost and how it has become the symbol of God’s presence in the life of believers in Pentecostal Churches in Botswana today. The paper interrogates glossolalia on whether it is divine language or human language spoken by people who are emotionally charged. This research was undertaken in order to understand glossolalia better, since it is a contested area not only among Christians but also in other world religions where this phenomenon is widely manifested. The present work shows that while theologians are justified to consider glossolalia as divine language, there are indications that in some instances speaking in tongues can be a result of anxiety and human attempts to prove that the Holy Spirit is truly present in one’s spiritual life. This conclusion has been reached especially in cases where it has been found that glossolalia is a learned language. Key words: Pentecostal Churches; glossolalia; divine-speech; speaking in tongues; man-made language; ecstatic utterance; anxiety, depression; healing; kingdom of God; kingdom of the devil. -

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues As Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues as Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives Eben de Jager Abstract In contemporary Pentecostal and Charismatic circles glossolalia is Keywords often referred to as the tongues of angels, with 1 Corinthians 13:1 Tongues of angels, angeloglossy, xenolalia, glossolalia, being quoted. Yet writings on the tongues of angels available in hebraeophone. the first century and the Judaean context from which Paul wrote do not support such a narrative. In addition, the Corinthian About the Author1 context and the writings of the Church Fathers also paint a picture Eben de Jager not aligned with the contemporary view. An analysis of 1 Masters Degree, UNISA. He is a member of Spirasa (The Spirituality Corinthians 13:1–3 shows it to be a weak support for establishing Association of South Africa). the concept of contemporary ‘angelic language’. Other influences may have given rise to the idea of glossolalia as the tongues of angels, but the Bible does not appear to support such a view. 1 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the beliefs of the South African Theological Seminary. Conspectus—The Journal of the South African Theological Seminary ISSN 1996-8167 https://www.sats.edu.za/conspectus/ This article: https://www.sats.edu.za/de-jager-an-evaluation-of-speaking-in-tongues Conspectus, Volume 28, September 2019 35 1. Introduction There are many different views on the gift of tongues, or glossolalia, in Christian circles today. Cartledge (2000:136–138) lists twelve possibilities of what the linguistic nature of glossolalia might be, based on his study of various scholars’ work. -

Interrogating the Comparative Method: Whither, Why, and How?1

religions Article Interrogating the Comparative Method: Whither, Why, and How?1 Barbara A. Holdrege Department of Religious Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-3130, USA; [email protected] Received: 15 January 2018; Accepted: 26 January 2018; Published: 12 February 2018 Abstract: This essay seeks to illuminate the problematics, methods, and dynamics of comparison by interrogating how certain analytical categories in the study of religion, such as scripture and the body, can be fruitfully reimagined through a comparative analysis of their Hindu and Jewish instantiations. I consider a range of issues that are critical to any productive comparative study, and I reflect more specifically on the principal components of my own comparative method in light of Oliver Freiberger’s analytical framework: the goals of comparative analysis; the modes of comparison; the parameters that define the scope and the scale of the comparative inquiry; and the operations involved in the comparative process, beginning with selection of the specific traditions and analytical categories to be addressed and formulation of the organizational design of the study and culminating in the re-visioned categories and models in the study of religion that constitute the fruits of the comparative inquiry. Keywords: comparative method; analytical categories; models of religious tradition; Hinduisms; Judaisms; Hindu-Jewish comparative studies; scripture; body; Veda; Torah Jonathan Z. Smith, in his 1982 essay “In Comparison a Magic Dwells,” surveys and critiques four basic modes of comparison—ethnographic, encyclopedic, morphological, and evolutionary— together with their more recent variants, and concludes that none of the proposed methods is adequate. Yet he suggests that the comparative enterprise should not thereby be abandoned, for the process of comparison is a constitutive aspect of human thought and is critical to the task of the scholar of religion. -

Inclusive Language Inside the Christian Community

Inclusive Language Inside the Christian Community Senior Thesis By Hope Ariel Brown Department of Women Studies University of Washington June 2004 Advisor: Kathleen D. Noble, Ph.D For my mom, Charlotte Joy Lindberg with love and gratitude 2 Acknowledgements I have crossed paths with numerous individuals during the course of this project, all of whom I would like to recognize with joy and appreciation. First and foremost I must thank my inspiration for this project: my mom. This thesis would not have been created without countless discussions with my mom, whose vast knowledge, spiritual energy, love and devotion allowed me to write to the best of my potential. Thank you to each of the women interviewed: Sally Balmer, Sister Claudette Conrad, Mary-Evelyn Long, Deborah Sunoo, and Caryl Menkhus. I would also like to recognize my advisor Kate Noble, whose calm manner and encouraging words allowed me to organize my thoughts with both clarity and wild energy. Thank you to Angela Ginorio for guiding my first creative efforts, Kevin Mihata for a quick introduction to content analysis and qualitative methods, Prairie for her brilliant editing skills and emotional support, Kima for being herself and for centering me, Jannelle for taking me on walks, Peter for his love, all friends and family who listened with attentive and supportive ears, and that Divine energy, which pulses its way through all written words. 3 Table of Contents I. Introduction…………………………………………….5 II. Literature Review………………………………………9 III. Research Questions……………………………………18 IV. Methods………………………………………………..20 V. Results…………………………………………………22 VI. Discussion……………………………………………..46 VII. Limitations…………………………………………….49 VIII. Conclusion…………………………………………….50 IX. -

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon the Theosophical Seal a Study for the Student and Non-Student

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon The Theosophical Seal A Study for the Student and Non-Student by Arthur M. Coon This book is dedicated to all searchers for wisdom Published in the 1800's Page 1 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION PREFACE BOOK -1- A DIVINE LANGUAGE ALPHA AND OMEGA UNITY BECOMES DUALITY THREE: THE SACRED NUMBER THE SQUARE AND THE NUMBER FOUR THE CROSS BOOK 2-THE TAU THE PHILOSOPHIC CROSS THE MYSTIC CROSS VICTORY THE PATH BOOK -3- THE SWASTIKA ANTIQUITY THE WHIRLING CROSS CREATIVE FIRE BOOK -4- THE SERPENT MYTH AND SACRED SCRIPTURE SYMBOL OF EVIL SATAN, LUCIFER AND THE DEVIL SYMBOL OF THE DIVINE HEALER SYMBOL OF WISDOM THE SERPENT SWALLOWING ITS TAIL BOOK 5 - THE INTERLACED TRIANGLES THE PATTERN THE NUMBER THREE THE MYSTERY OF THE TRIANGLE THE HINDU TRIMURTI Page 2 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon THE THREEFOLD UNIVERSE THE HOLY TRINITY THE WORK OF THE TRINITY THE DIVINE IMAGE " AS ABOVE, SO BELOW " KING SOLOMON'S SEAL SIXES AND SEVENS BOOK 6 - THE SACRED WORD THE SACRED WORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Page 3 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION I am happy to introduce this present volume, the contents of which originally appeared as a series of articles in The American Theosophist magazine. Mr. Arthur Coon's careful analysis of the Theosophical Seal is highly recommend to the many readers who will find here a rich store of information concerning the meaning of the various components of the seal Symbology is one of the ancient keys unlocking the mysteries of man and Nature. -

Fully Human and Fully Divine: the Birth of Christ and the Role of Mary

Religions 2015, 6, 172–181; doi:10.3390/rel6010172 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Commentary Fully Human and Fully Divine: The Birth of Christ and the Role of Mary Ann Milliken Pederson 1,*, Gretchen Spars-McKee 2,†, Elisa Berndt 1,†, Morgan DePerno 1 and Emily Wehde 1 1 Department of Religion, Augustana College, Sioux Falls, SD 57105, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (E.B.); [email protected] (M.D.); [email protected] (E.W.) 2 Sanford School of Medicine, The University of South Dakota, 1400 W. 22nd Street, Sioux Falls, SD 57105, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-605-274-5489; Fax: +1-605-274-5288. Academic Editor: Yudit Greenberg Received: 12 December 2014 / Accepted: 27 February 2015 / Published: 6 March 2015 Abstract: The task given to us for this article was to offer theological responses to, “Can modern biology interpret the mystery of the birth of Christ?” by Giuseppe Benagiano and Bruno Dallapiccola. We are female Protestant theologians and respond to the issues from this perspective. The Christian confession of the virgin birth of Jesus (stated within the Apostles and Nicene creeds) is a statement of faith that God became incarnate through the power of the Holy Spirit in the flesh of the human Jesus and, likewise, that God continues to become incarnate in our flesh and in the messy details of our lives. The mystery and miracle of the birth of Jesus has much more to do with the incarnation of God in human flesh and in God’s spirit at work in and with Mary, than to do with Mary’s gynecological or parthenogenical mechanisms. -

Grounding the Angels

––––––––––––––––––––––– Grounding the Angels: An attempt to harmonise science and spiritism in the celestial conferences of John Dee ––––––––––––––––––––––– A thesis submitted by Annabel Carr to the Department of Studies in Religion in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) University of Sydney ––––––––––––– Supervised by Dr Carole Cusack June, 2006 Acknowledgements Thank you to my darling friends, sister and cousin for their treasurable support. Thank you to my mother for her literary finesse, my father for his technological and artistic ingenuity, and my parents jointly for remaining my most ardent and loving advocates. Thank you to Dominique Wilson for illuminating the world of online journals and for her other kind assistance; to Robert Haddad of the Sydney University Catholic Chaplaincy Office for his valuable advice on matters ecclesiastical; to Sydney University Inter-Library Loans for sourcing rare and rarefied material; and to the curators of Early English Books Online and the Rare Books Library of Sydney University for maintaining such precious collections. Thank you to Professor Garry Trompf for an intriguing Honours year, and to each member of the Department of Studies in Religion who has enriched my life with edification and encouragement. And thank you most profoundly to Dr Carole Cusack, my thesis supervisor and academic mentor, for six years of selfless guidance, unflagging inspiration, and sagacious instruction. I remain forever indebted. List of Illustrations Figure 1. John Dee’s Sigillum Dei Ameth, recreated per Sloane MS. 3188, British Museum Figure 2. Edward Kelley, Ebenezer Sibly, engraving, 1791 Figure 3. The Archangel Leaving the Family of Tobias, Rembrandt, oil on canvas, 1637 Figure 4. -

The Kabalah and the Kabalists No

Adyar Pamphlets The Kabalah and the Kabalists No. 105 The Kabalah and the Kabalists by H.P. Blavatsky Reprinted from Lucifer Vol X Published in 1919 Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, Chennai [Madras] India The Theosophist Office, Adyar, Madras. India [The spelling of the word is various; some write Cabbalah, others Kabbalah. The latest writers have introduced a new spelling as more consonant with the Hebrew manner of writing the word and made it Quabalah. This is more grammatical, perhaps, but as no Englishman will ever pronounce a foreign name or word but in an Englishified way, to write the term simply Kabalah seems less pretentious and answers as well.] UNIVERSAL aspirations, especially when impeded and suppressed in their free manifestation, die out but to return with tenfold power. They are cyclic, like every other natural phenomenon, whether mental or cosmic, universal or national. Dam a river in one place, and the water will work its way into another, and break out through it like a torrent. One of such universal aspirations, the strongest perhaps in man’s nature, is the longing to seek for the unknown; an ineradicable desire to penetrate below the surface of things, a thirst for the knowledge of that which is hidden from others. Nine children out of ten will break their toys to see what there is inside. It is an innate feeling and is Protean in form. It rises from the ridiculous (or perhaps rather from the reprehensible) to the sublime, for it is limited to indiscreet inquisitiveness, prying into neighbours secrets, in the uneducated, and it expands in the cultured into that love for knowledge which ends in leading them to the summits of science, and fills the Academies and the Royal Institutions with learned men. -

Water, Word and Name: the Shifting Pragmatics of the Sotah/Suspected Adulteress Ritual

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Water, Word and Name: The Shifting Pragmatics of the Sotah/Suspected Adulteress Ritual Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/70m4m5w4 Author Janowitz, Naomi Publication Date 2014 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Water, Word and Name: The Shifting Pragmatics of the Sotah/Suspected Adulteress Ritual Forthcoming in Literature or Liturgy? Early Christian Hymns and Prayers in their Literary and Liturgical Context in Antiquity Liturgy is a special kind of conversation, words sometimes addressed to the gods and sometimes about them. These conversations are part of complex performances that combine words with the use of all sorts of objects. While, as we will discuss below, some ritual acts do not include the use of any words at all, this paper examines the Sotah/Suspected Adulteress Rite where liturgy is of central importance. Liturgy is a compelling example of the multi- functionality of language because words are spoken to bring about concrete results. That is, participating in liturgy is a direct mode of social action (blessing, marrying, etc.). These modes of action overlap with but are distinct from that of other types of texts (novels) because of the many different ways what-is-said maps onto what-is-done . Liturgical formulas are highly context-creating, for example, invoking the presence of a deity or transforming a place from profane to sacred. Because it so obviously attributes power to words, liturgy is a vivid example of “the central place it [language] occupies in the social construction of reality” . Certainly we could analyze liturgy from many angles, seeking, for example, an historical kernel in vivid imagery1 or a 1 See for example the case made by Philip Alexander that the imagery of the celestial court in hekhalot texts is closest to that of the court at the time of Diocletian . -

1 Thinking About Religion Through Wittgenstein Talal Asad in What

Thinking about Religion through Wittgenstein Talal Asad ABSTRACT This essay is an attempt at thinking through Wittgenstein’s philosophy in order to clarify some aspects of what people call “religion.” Central to it is an exploration of the polarity between belief and practice, and an attempt to reframe that polarity in terms of the mutually interconnected processes of being and learning. It seeks to address the old question of persuadibility, of what makes for conviction and effective critique, particularly in relation to faith in God and in “another world.” It then attempts to apply Wittgenstein’s insights to fundamental disagreements in the Islamic tradition over the proper understanding of apparently contradictory representations of God in the Qur’an. Finally, it takes up the question of what Wittgenstein called “the craving for generality,” and thus the part abstraction plays in the progressive thrust of our secular, capitalist form of life. Keywords religious reasons, tradition, practice, abstraction, the secular In what follows I try to think about religious tradition through Wittgenstein’s writings. My aim is not to provide an account of his view of religion, and still less to make a contribution to anthropological theory. It is, in the most banal sense, an exercise in thinking. I turn to his philosophy to help me clarify some ideas about what is called “religion” in English. I am not, of course, looking to construct a universal definition of that word. My usage of the word “religion” in this piece as well as in other writings assumes that it is not always necessary to provide a definition in order to make its meaning comprehensible because and to the extent that its grammar already does that.1 Following Wittgenstein, I take it that the sense of particular words shifts together with the practices of ordinary life. -

When the Gods Speak: Oracular Communication and Concepts of Language in Sophocles by Amy Nicole Pistone a Dissertation Submitted

When the Gods Speak: Oracular Communication and Concepts of Language in Sophocles by Amy Nicole Pistone A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Professor Ruth Scodel, Chair Professor Sara Ahbel-Rappe Professor Richard Janko Associate Professor Ezra Keshet Amy Nicole Pistone [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-2822-7154 © Amy Nicole Pistone 2017 For my mom, who taught me to love literature before I could read it on my own, and my dad, who taught me that a challenge builds character. ii Acknowledgments I am sure that I will not adequately thank everyone who contributed to my completing this project, and I apologize in advance for that. The list is long indeed. First, I owe my committee a great deal, and my chair above all. Ruth Scodel gave me the room to explore my own ideas and the support to help make something of them. I needed to spin my wheels a bit before I started making any progress on my dissertation, and she allowed me space to spin and then also helped set me on a productive path. For that I am deeply grateful, and for the wealth of knowledge she has shared with me while still allowing my research to be my own. She has taught me a great deal about how to be a scholar and an instructor, as well as a colleague, and I will take those lessons with me. I also owe a great debt to my committee members—Richard Janko, Sara Ahbel-Rappe, and Ezra Keshet—all of whom have helped refine my ideas and pointed me toward useful scholarship to develop my research. -

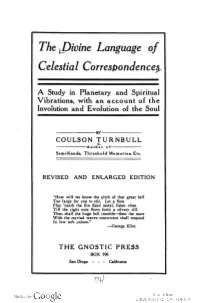

The Divine Language of Celestial Correspondences $3.00 Sema-Kanda, a Mystical Romance - -- $1.25

The Divine Language of Celestial Correspondences A Study in Planetary and Spiritual Vibrations, with an account of the Involution and Evolution of the Soul BY COULSO N T URNBULL Author of Semi-Kanda, Threshold Memories, Etc. REVISED AND ENLARGED EDITION “How will we know the pitch of that great bell Too large for you to stir. Let a flute Play 'neath the fire fixed metal, listen close Till the right note flows forth a silvery rill. Then shall the huge bell tremble—then the mass With the myriad waves concurrent shall respond In low soft unison.” —George Eliot. THE GNOSTIC PRESS BOX 596 - San Diego : :: California Works by Coulson Turnbull: The Divine Language of Celestial Correspondences $3.00 Sema-Kanda, A Mystical Romance - -- $1.25 The Mystical Meaning of the Hebrew Scriptures (Twelve Lessons) -- $3.00 Giordano Bruno. His Life and Teachings - - $1.00 The Rising Zodiacal Sign Its Meaning and Progno stics. Cloth - -- $ .50 CONTENTS Chapter Page Preface ..... ... .. ...... ... ....... .. 5 PART ONE The Gospel of Correspondences. .. .. .. ... 7 II The Soul and the Sidereal Man ............ 14 III The Esoteric Symbolism of the Planets. ...... 20 Mystical Interpretation 25 IV The of the Zodiac. ..... - The Kabalistical Interpretation of the Twelve Houses and Numbers. .. .... .. 32 VI The Evolution and Involution of Soul ...... 36 VII Plants, Leaves, Spirals and Their Occult Analogy to the Stars. ............. ... ...... .. 46 VIII The Fiery Signs, Aries, Leo and Sagitarius. .... 51 IX The Earthy Signs, Taurus, Virgo and Capricorn. .. 59 The Airy Signs, Gemini, Libra and Aquarius. 67 XI The Watery Signs, Cancer, Scorpio and Pisces. 74 XII The Character of the Planets.