When the Gods Speak: Oracular Communication and Concepts of Language in Sophocles by Amy Nicole Pistone a Dissertation Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oneiromancy in the Bible

Oneiromancy 1 Oneiromancy in the Bible So what did the medieval or early Renaissance reader make of oneiromancy--the process of divination through dreams? Even through the King James Bible would not appear in English until the 1600s, most educated readers would be familiar with various biblical accounts of divinely inspired dreams. These pages list biblical passages that Christians in the medieval period considered important. In some cases, there is some confusion in the Latin text as to whether or not the events described took place as a dream (somnium) during sleep (somnus), or as a waking vision (visio). To differentiate, I include the Latin below. Note that the phrases "in somno" and in somnis" can mean "in dreams" or "while asleep." Genesis 20:3-7 (somnium): In the story of Abraham and Sarah, a male dreamer (Abimelech) is warned against taking Sarah from Abraham. 28:12-15 (in somnis) Jacob's dream of a ladder, with angels moving up and down it. 31:10-13 (in somnis) Angel appears to Jacob in a dream, shows him Laban's sheep producing speckled and striped ewes, which will be his according to agreement. 31:24 (in somnis) Laban warned by God in dream not to speak harshly to Jacob. 37:5-9 (ut visum somnium) Joseph hated by his brothers, he tells them a dream he already dreamed; the frame is a narrator telling a past dream in which Jacob's brothers' sheaves stand in a field with sheaves bowing down to his. Then the sun and moon and stars worship it as well. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Glossolalia: Divine Speech Or Man-Made Language? a Psychological Analysis of the Gift of Speaking in Tongues in the Pentecostal Churches in Botswana

GLOSSOLALIA: DIVINE SPEECH OR MAN-MADE LANGUAGE? A PSYCHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE GIFT OF SPEAKING IN TONGUES IN THE PENTECOSTAL CHURCHES IN BOTswaNA James N Amanze and Tino Shanduka Department of Theology and Religious Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Botswana [email protected] ABSTRACT Glossolalia is a very important element in the life of Pentecostal Churches and is at the centre of their spirituality. This paper examines the gift of speaking in tongues from a psychological perspective in order to find out what psychologists say about this very important gift of the Holy Spirit. The paper begins by looking at the history of speaking in tongues in the Church from the day of Pentecost and how it has become the symbol of God’s presence in the life of believers in Pentecostal Churches in Botswana today. The paper interrogates glossolalia on whether it is divine language or human language spoken by people who are emotionally charged. This research was undertaken in order to understand glossolalia better, since it is a contested area not only among Christians but also in other world religions where this phenomenon is widely manifested. The present work shows that while theologians are justified to consider glossolalia as divine language, there are indications that in some instances speaking in tongues can be a result of anxiety and human attempts to prove that the Holy Spirit is truly present in one’s spiritual life. This conclusion has been reached especially in cases where it has been found that glossolalia is a learned language. Key words: Pentecostal Churches; glossolalia; divine-speech; speaking in tongues; man-made language; ecstatic utterance; anxiety, depression; healing; kingdom of God; kingdom of the devil. -

View the Slides

some words about words This talk was written about North American English, but English is not a single language with a single standard meaning for every word or phrase. It’s possible that the specific things I say in this talk will not apply to the dialect of English that you speak in your workplace. Unfortunately, I don’t have the experience I would need to be able to localize this talk to the major dialects of English people speak in this part of the world. So I will begin by talking about the theories of language I drew on in writing this talk. Understanding these theories can help you understand what to look for in your workplace and your dialect(s) of English. what to listen for Direct insults have no place in a retrospective (or, I would argue, any workplace), but they’re also reasonably easy to identify, and they’re generally an issue for a company’s management, so insults and other unambiguous mean remarks are mostly not what I am going to to talk about today. I am going to talk about subtle words and phrases that may make you feel bad but leave you feeling confused about why. These are regionally and culturally variant- subtle insults or compliments depend on you knowing what the speaker considers good and bad and what words have good or bad connotations, and those things are strongly influenced by culture and region (even within countries). So I will start by giving you some tools to use when thinking about the meanings of words in English. -

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues As Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues as Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives Eben de Jager Abstract In contemporary Pentecostal and Charismatic circles glossolalia is Keywords often referred to as the tongues of angels, with 1 Corinthians 13:1 Tongues of angels, angeloglossy, xenolalia, glossolalia, being quoted. Yet writings on the tongues of angels available in hebraeophone. the first century and the Judaean context from which Paul wrote do not support such a narrative. In addition, the Corinthian About the Author1 context and the writings of the Church Fathers also paint a picture Eben de Jager not aligned with the contemporary view. An analysis of 1 Masters Degree, UNISA. He is a member of Spirasa (The Spirituality Corinthians 13:1–3 shows it to be a weak support for establishing Association of South Africa). the concept of contemporary ‘angelic language’. Other influences may have given rise to the idea of glossolalia as the tongues of angels, but the Bible does not appear to support such a view. 1 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the beliefs of the South African Theological Seminary. Conspectus—The Journal of the South African Theological Seminary ISSN 1996-8167 https://www.sats.edu.za/conspectus/ This article: https://www.sats.edu.za/de-jager-an-evaluation-of-speaking-in-tongues Conspectus, Volume 28, September 2019 35 1. Introduction There are many different views on the gift of tongues, or glossolalia, in Christian circles today. Cartledge (2000:136–138) lists twelve possibilities of what the linguistic nature of glossolalia might be, based on his study of various scholars’ work. -

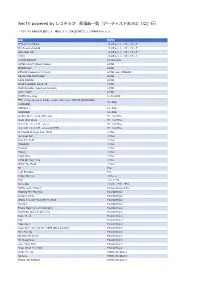

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Divination in the Ancient Near East Humans Are Creatures That Thrive on Information

1 Divination in the Ancient Near East Humans are creatures that thrive on information. We have always tried to learn what was going on around us, particularly in times of danger or crisis. If we cannot find hard facts, we will make something up. Divination in the ancient world helped to soothe this need, but it served other functions as well. The ultimate basis of divination was a sense that divine action and intent has a ripple effect across the rest of the physical world. These manifest themselves in subtle changes and events both large and small that the wise could identify and interpret. Usually when we talk of divination we focus on the mechanics, and we will do that here to some extent. Perhaps the most famous form of divination among Israel’s neighbors and especially the civilizations of Mesopotamia was hepatoscopy or divining based on marks or deformations of the liver of a sacrificial animal. This was part of a larger form of divination called extispicy, which tried to discern divine intent by examining an animal’s internal organs. The Figure 1: Etruscan Bronze Mirror of Chalchas the Seer Babylonian and Assyrians were Reading a Liver (Vatican: Gregorian Museum, Rome, not the only ones to practice cat # 12240). this; one finds it throughout the Mediterranean basin, but they brought it to unparalleled levels of sophistication. One obvious question is, “why a liver?” The most likely reason is that it was something beyond reach until it was extracted by the diviner. Until then, no one could touch it or manipulate it, and so it constituted something on which the action and intent of the gods could write itself without human interference or manipulation. -

Michigan Winter Tournament Packet 15

Michigan Winter Tournament "The Holy Roman Empire of Tournaments" Edited by: Harris Bunker, Emmett Laurie, Evan Lynch, Matt Mitchell, Eric Mukherjee, Jacob O'Rourke, Rudra Ranganathan, Conor Thompson, Jeremy Tsai, and Chandler West Written by: The editors, Mollie Bakal, Austin Foos, Beverly Fu, Colton Graham, James Hadley, Sean Higgins, Tyler McMaken, Ameya Phadnis, Aleija Rodriguez, James Stevenson, and Allan VanZandt Packet 15 Tossups: 1. Rulers with this title employed a series of lash-bearers to patrol the streets while ruling a city where they stripped voting rights from everyone except a group called "the Included." After overthrowing the Bacchiadae, Cypselos took this title, as did his son Periander. Harmodius and Aristogeiton planned an attack targeted a ruler with this title at the 514 BC Panathenaic Festival, where they killed Hipparchus but failed to kill the final holder in a line of rulers who took this title, Hippias. (*) Thrasybulus led a 403 BC uprising to overthrow a regime whose rulers took this title. That regime whose leaders took this title was imposed on a city after its defeat in the Peloponnesian War. For 10 points, give this title, held by "Thirty" rulers in a pro-Spartan oligarchy that ruled Athens. ANSWER: tyrant <Ranganathan, Other History> 2. They're not relative clauses, but parts of these expressions can undergo pied-piping, a process that can result in preposition stranding. Adjunct clauses and left branch clauses are among the so-called "islands" which can prevent the syntactic movement of words marking these expressions. Speakers wishing to hedge or be polite might append statements or commands with the (*) "tag" variety of these expressions. -

The Tyrannies in the Greek Cities of Sicily: 505-466 Bc

THE TYRANNIES IN THE GREEK CITIES OF SICILY: 505-466 BC MICHAEL JOHN GRIFFIN Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Classics September 2005 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to thank the Thomas and Elizabeth Williams Scholarship Fund (Loughor Schools District) for their financial assistance over the course of my studies. Their support has been crucial to my being able to complete this degree course. As for academic support, grateful thanks must go above all to my supervisor at the School of Classics, Dr. Roger Brock, whose vast knowledge has made a massive contribution not only to this thesis, but also towards my own development as an academic. I would also like to thank all other staff, both academic and clerical, during my time in the School of Classics for their help and support. Other individuals I would like to thank are Dr. Liam Dalton, Mr. Adrian Furse and Dr. Eleanor OKell, for all their input and assistance with my thesis throughout my four years in Leeds. Thanks also go to all the other various friends and acquaintances, both in Leeds and elsewhere, in particular the many postgraduate students who have given their support on a personal level as well as academically. -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Ancient Greek Divination by Sarah Iles Johnston Blackwell Ancient Religions

Ancient Greek Divination by Sarah Iles Johnston Blackwell Ancient Religions. Malden, MA/Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. Pp. xiv + 193. ISBN 978--1--4051--1573--5.Paper $27.95 Reviewed by Joshua J. Reynolds Center for Hellenic Studies, Washington, DC [email protected] This book provides an overview of Greek divination as a religious phenomenon. In particular, the author seeks to describe and explain both the details of Greek divinatory practices and how the ancients conceptualized those practices. As the title suggests, the discussion is restricted to divination as practiced in the Greek world, although the author does make abundant use of evidence from a much wider vari- ety of sources and time periods, including Roman and Christian writ- ers. The straightforward writing, logical organization, and absence of footnotes make the book accessible to a general audience; while the erudition, critical approach to prior scholarship, and thorough bibli- ography accommodate both classicists in general and specialists. The book contains five chapters: an introduction, two chapters devoted to institutional oracles, and two chapters covering indepen- dent diviners (including magicians). In chapter 1, the author sets out to justify her study in terms of the pervasiveness of divination, not only in ancient times but in modern cultural contexts as well. She points to the desire for divina- tory knowledge as a ‘basic human need’ [4]. The difference, however, between moderns and ancients is the degree of theoretical reflection among the latter. The ancients, Johnston argues, were theoretically inclined towards divination because the practice allowed mortals the possibility of conversing with the gods, as opposed to other religious practices, such as prayer or sacrifice, which did not return immediate answers. -

Collins Magic in the Ancient Greek World.Pdf

9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page i Magic in the Ancient Greek World 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page ii Blackwell Ancient Religions Ancient religious practice and belief are at once fascinating and alien for twenty-first-century readers. There was no Bible, no creed, no fixed set of beliefs. Rather, ancient religion was characterized by extraordinary diversity in belief and ritual. This distance means that modern readers need a guide to ancient religious experience. Written by experts, the books in this series provide accessible introductions to this central aspect of the ancient world. Published Magic in the Ancient Greek World Derek Collins Religion in the Roman Empire James B. Rives Ancient Greek Religion Jon D. Mikalson Forthcoming Religion of the Roman Republic Christopher McDonough and Lora Holland Death, Burial and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt Steven Snape Ancient Greek Divination Sarah Iles Johnston 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page iii Magic in the Ancient Greek World Derek Collins 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page iv © 2008 by Derek Collins blackwell publishing 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Derek Collins to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.