The Classic-Gaming Bookcast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Res2k Gamelist ATARI 2600

RES2k Gamelist ATARI 2600 Carnival 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe Casino 32 in 1 Game Cartridge Cat Trax (Proto) 2005 Minigame Multicart (Unl) Cathouse Blues A-VCS-tec Challenge (Unl) Cave In (Unl) Acid Drop Centipede Actionauts (Proto) Challenge Adventure Championship Soccer Adventures of TRON Chase the Chuckwagon Air Raid Checkers Air Raiders Cheese (Proto) Air-Sea Battle China Syndrome Airlock Chopper Command Alfred Challenge (Unl) Chuck Norris Superkicks Alien Greed (Unl) Circus Atari Alien Greed 2 (Unl) Climber 5 (Unl) Alien Greed 3 (Unl) Coco Nuts Alien Codebreaker Allia Quest (Unl) Colony 7 (Unl) Alpha Beam with Ernie Combat Two (Proto) Amidar Combat Aquaventure (Proto) Commando Raid Armor Ambush Commando Artillery Duel Communist Mutants from Space AStar (Unl) CompuMate Asterix Computer Chess (Proto) Asteroid Fire Condor Attack Asteroids Confrontation (Proto) Astroblast Congo Bongo Astrowar Conquest of Mars (Unl) Atari Video Cube Cookie Monster Munch Atlantis II Cosmic Ark Atlantis Cosmic Commuter Atom Smasher (Proto) Cosmic Creeps AVGN K.O. Boxing (Unl) Cosmic Invaders (Unl) Bachelor Party Cosmic Swarm Bachelorette Party Crack'ed (Proto) Backfire (Unl) Crackpots Backgammon Crash Dive Bank Heist Crazy Balloon (Unl) Barnstorming Crazy Climber Base Attack Crazy Valet (Unl) Basic Math Criminal Persuit BASIC Programming Cross Force Basketball Crossbow Battlezone Crypts of Chaos Beamrider Crystal Castles Beany Bopper Cubicolor (Proto) Beat 'Em & Eat 'Em Cubis (Unl) Bee-Ball (Unl) Custer's Revenge Berenstain Bears Dancing Plate Bermuda Triangle Dark -

Rétro Gaming

ATARI - CONSOLE RETRO FLASHBACK 8 GOLD ACTIVISION – 130 JEUX Faites ressurgir vos meilleurs souvenirs ! Avec 130 classiques du jeu vidéo dont 39 jeux Activision, cette Atari Flashback 8 Gold édition Activision saura vous rappeler aux bons souvenirs du rétro-gaming. Avec les manettes sans fils ou vos anciennes manettes classiques Atari, vous n’avez qu’à brancher la console à votre télévision et vous voilà prêts pour l’action ! CARACTÉRISTIQUES : • 130 jeux classiques incluant les meilleurs hits de la console Atari 2600 et 39 titres Activision • Plug & Play • Inclut deux manettes sans fil 2.4G • Fonctions Sauvegarde, Reprise, Rembobinage • Sortie HD 720p • Port HDMI • Ecran FULL HD Inclut les jeux cultes : • Space Invaders • Centipede • Millipede • Pitfall! • River Raid • Kaboom! • Spider Fighter LISTE DES JEUX INCLUS LISTE DES JEUX ACTIVISION REF Adventure Black Jack Football Radar Lock Stellar Track™ Video Chess Beamrider Laser Blast Asteroids® Bowling Frog Pond Realsports® Baseball Street Racer Video Pinball Boxing Megamania JVCRETR0124 Centipede ® Breakout® Frogs and Flies Realsports® Basketball Submarine Commander Warlords® Bridge Oink! Kaboom! Canyon Bomber™ Fun with Numbers Realsports® Soccer Super Baseball Yars’ Return Checkers Pitfall! Missile Command® Championship Golf Realsports® Volleyball Super Breakout® Chopper Command Plaque Attack Pitfall! Soccer™ Gravitar® Return to Haunted Save Mary Cosmic Commuter Pressure Cooker EAN River Raid Circus Atari™ Hangman House Super Challenge™ Football Crackpots Private Eye Yars’ Revenge® Combat® -

BOB CORRITORE a Blues Life Order Today Click Here! Four Print Issues Per Year

BOB CORRITORE A Blues Life Order Today Click Here! Four Print Issues Per Year Every January, April, July, and October get the Best In Blues delivered right t0 you door! Artist Features, CD, DVD Reviews & Columns. Award-winning Journalism and Photography! Order Today Click Here! 20-0913-Blues Music Magazine Full Page 4C bleed.indd 1 17/11/2020 09:17 BLUES MUSIC ONLINE December 01, 2020 - Issue 23 Table Of Contents 06 - BOB CORRITORE A Blues Life By Art Tipaldi 16 - SEVEN NEW CD REVIEWS By Various Writers 31 - BLUES MUSIC SAMPLER DOWNLOAD CD Sampler 26 - July 2020 Illustration by Tom Walbank COVER PHOTOGRAPHY © DAVE BLAKE Read The News Click Here! All Blues, All The Time, AND It's FREE! Get Your Paper Here! Read the REAL NEWS you care about: Blues Music News! FEATURING: - Music News - Breaking News - CD Reviews - Music Store Specials - Video Releases - Festivals - Artists Interviews - Blues History - New Music Coming - Artist Profiles - Merchandise - Music Business Updates BOB CORRITORE A Blues Life By Art Tipaldi PHOTOGRAPHY © JEFF FASANO lues Music Magazine: Primer/Bob Corritore collaborative The feature will include all release and I think this one is our aspects of your musical best so far. I’ve known John since Bcareer to include but not limited to: the mid-1970s from going to see musician, club owner, producer, Junior Wells at Theresa’s Lounge record label, newsletter writer, on the South Side. I’ve watched and founder of the Southwest John’s progression to the Muddy Musical Arts Foundation. Did I Waters band to Magic Slim & The miss anything? Teardrops to launching his own brilliant solo career. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Elec~Ronic Gantes Formerly Arcade Express

Elec~ronic Gantes Formerly Arcade Express Tl-IE Bl-WEEKLY ELECTRONIC GAMES NEWSLETTER VOLUME TWO, NUMBER NINE DECEMBER 4, 1983 SINGLE ISSUE PRICE $2.00 ODYSSEY EXITS The company that created the home arcading field back in 1970 has de VIDEOGAMING cided to pull in its horns while it takes its future marketing plans back to the drawing board. The Odyssey division of North American Philips has announced that it will no longer produce hardware for its Odyssey standard programmable videogame system. The publisher is expected to play out the string by market ing the already completed "War Room" and "Power Lords" cartridges for ColecoVision this Christmas season, but after that, it's plug-pulling time. Is this the end of Odyssey as a force in the gaming world? Only temporarily. The publisher plans to keep a low profile for a little while until its R&D department pushes forward with "Operation Leapfrog", the creation of N.A.P. 's first true computer. 20TH CENTURY FOX 20th Century Fox Videogames has left the game business, saying, THROWS IN THE TOWEL "Enough is enough!" According to Fox spokesmen, the canny company didn't actually experience any heavy losses. However, the foxy powers-that-be decided that the future didn't look too bright for their brand of video games, and that this is a good time to get out. The company, whose hit games included "M*A*S*H", "MegaForce", "Flash Gordon" and "Alien", reportedly does not have a large in ventory of stock on hand, and expects to experience no large financial losses as it exits the gaming business. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

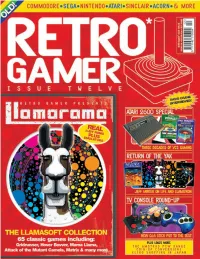

Retro Gamer Speed Pretty Quickly, Shifting to a Contents Will Remain the Same

Untitled-1 1 1/9/06 12:55:47 RETRO12 Intro/Hello:RETRO12 Intro/Hello 14/9/06 15:56 Page 3 hel <EDITORIAL> >10 PRINT "hello" Editor = >20 GOTO 10 Martyn Carroll >RUN ([email protected]) Staff Writer = Shaun Bebbington ([email protected]) Art Editor = Mat Mabe Additonal Design = Mr Beast + Wendy Morgan Sub Editors = Rachel White + Katie Hallam Contributors = Alicia Ashby + Aaron Birch Richard Burton + Keith Campbell David Crookes + Jonti Davies Paul Drury + Andrew Fisher Andy Krouwel + Peter Latimer Craig Vaughan + Gareth Warde Thomas Wilde <PUBLISHING & ADVERTISING> Operations Manager = Debbie Whitham Group Sales & Marketing Manager = Tony Allen hello Advertising Sales = elcome Retro Gamer speed pretty quickly, shifting to a contents will remain the same. Linda Henry readers old and new to monthly frequency, and we’ve We’ve taken onboard an enormous Accounts Manager = issue 12. By all even been able to publish a ‘best amount of reader feedback, so the Karen Battrick W Circulation Manager = accounts, we should be of’ in the shape of our Retro changes are a direct response to Steve Hobbs celebrating the magazine’s first Gamer Anthology. My feet have what you’ve told us. And of Marketing Manager = birthday, but seeing as the yet to touch the ground. course, we want to hear your Iain "Chopper" Anderson Editorial Director = frequency of the first two or three Remember when magazines thoughts on the changes, so we Wayne Williams issues was a little erratic, it’s a used to be published in 12-issue can continually make the Publisher = little over a year old now. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Parasites — Excavating the Spectravideo Compumate

ghosts ; replicants ; parasites — Excavating the Spectravideo CompuMate These are the notes I used for my final presentation in the summer Media Archaeology Class, alongside images I used as slides. As such, they’re quite provisional, and once I have some time to hammer them into more coherent thoughts, I’ll update this post accordingly! So this presentation is about articulating and beginning the work of theorizing what I’m provisionally calling “computational parasites.” This is provisional because I don’t particularly like the term myself but I figured it would be good to give it a shorthand so I don’t have to be overvague or verbose about these objects and practices throughout this presentation. As most of you know, I came to this class with a set of research questions about a particular hack of the SNES game Super Mario World, wherein a YouTube personality was able to basically terraform the console original into playing, at least in form although we can talk about content, the iPhone game Flappy Bird. This video playing behind me is that hack. This hack is evocative for me for the way it’s 1) really fucking weird, in terms of pushing hardware and software to their limits, and 2) begins to help me think through ideas of the lifecycle of software objects, to pilfer a phrase from a Ted Chiang novella, and how these lifecycles are caught up in infrastructures of nostalgia, supply chains, and different kinds of materiality. But as fate would have it, I haven’t spent that much time with this hack this week because I got entranced by a different, just as weird object: the Spectravideo CompuMate. -

A Page 1 CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY Atari Text

A CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY 3D Tic-Tac Toe Atari Text 2 3D Tic-Tac Toe Sears Text 3 Action Pak Atari 6 Adventure Sears Text 3 Adventure Sears Picture 4 Adventures of Tron INTV White 3 Adventures of Tron M Network Black 3 Air Raid MenAvision 10 Air Raiders INTV White 3 Air Raiders M Network Black 2 Air Wolf Unknown Taiwan Cooper ? Air-Sea Battle Atari Text #02 3 Air-Sea Battle Atari Picture 2 Airlock Data Age Standard 3 Alien 20th Century Fox Standard 4 Alien Xante 10 Alpha Beam with Ernie Atari Children's 4 Arcade Golf Sears Text 3 Arcade Pinball Sears Text 3 Arcade Pinball Sears Picture 3 Armor Ambush INTV White 4 Armor Ambush M Network Black 3 Artillery Duel Xonox Standard 5 Artillery Duel/Chuck Norris Superkicks Xonox Double Ender 5 Artillery Duel/Ghost Master Xonox Double Ender 5 Artillery Duel/Spike's Peak Xonox Double Ender 6 Assault Bomb Standard 9 Asterix Atari 10 Asteroids Atari Silver 3 Asteroids Sears Text “66 Games” 2 Asteroids Sears Picture 2 Astro War Unknown Taiwan Cooper ? Astroblast Telegames Silver 3 Atari Video Cube Atari Silver 7 Atlantis Imagic Text 2 Atlantis Imagic Picture – Day Scene 2 Atlantis Imagic Blue 4 Atlantis II Imagic Picture – Night Scene 10 Page 1 B CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY Bachelor Party Mystique Standard 5 Bachelor Party/Gigolo Playaround Standard 5 Bachelorette Party/Burning Desire Playaround Standard 5 Back to School Pak Atari 6 Backgammon Atari Text 2 Backgammon Sears Text 3 Bank Heist 20th Century Fox Standard 5 Barnstorming Activision Standard 2 Baseball Sears Text 49-75108 -

Leader Development

Subscriptions: Free unit subscriptions are available by emailing the Editor at [email protected]. Include the complete mailing address (unit name, street address, and building number). Don’t forget to email the Editor when your unit moves, deploys, or redeploys to ensure continual receipt of the Bulletin. Reprints: Material in this Bulletin is not copyrighted (except where indicated). Content may be reprinted if the MI Professional Bulletin and the authors are credited. Our mailing address: MIPB, USAICoE, Box 2001, Bldg. 51005, Fort Huachuca, AZ 85613-7002 Commanding General Purpose: The U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence MG Robert P. Walters, Jr. publishes the Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin Chief of Staff (MIPB) quarterly under the provisions of AR 25-30. COL Douglas R. Woodall MIPB presents information designed to keep intelligence professionals informed of current and emerging devel- Chief Warrant Officer, MI Corps opments within the field and provides an open forum CW5 Matthew R. Martin in which ideas; concepts; tactics, techniques, and proce- Command Sergeant Major, MI Corps dures; historical perspectives; problems and solutions, etc., CSM Thomas J. Latter can be exchanged and discussed for purposes of profes- sional development STAFF: Editor Tracey A. Remus By order of the Secretary of the Army: [email protected] MARK A. MILLEY Associate Editor General, United States Army Maria T. Eichmann Chief of Staff Official: Design and Layout Emma R. Morris GERALD B. O’KEEFE Cover Design Administrative Assistant to the Emma R. Morris to the Secretary of the Army Military Staff 1803310 CPT John P. -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B.