Estonian Displaced Persons in Post-War Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Education: the Case of Estonia

Mare Oja History Education: The Case of Estonia https://doi.org/10.22364/bahp-pes.1990-2004.09 History Education: The Case of Estonia Mare Oja Abstract. This paper presents an overview of changes in history teaching/learning in the general education system during the transition period from Soviet dictatorship to democracy in the renewed state of Estonia. The main dimensions revealed in this study are conception and content of Estonian history education, curriculum and syllabi development, new understanding of teaching and learning processes, and methods and assessment. Research is based on review of documents and media, content analysis of textbooks and other teaching aids as well as interviews with teachers and experts. The change in the curriculum and methodology of history education had some critical points due to a gap in the content of Soviet era textbooks and new programmes as well as due to a gap between teacher attitudes and levels of knowledge between Russian and Estonian schools. The central task of history education was to formulate the focus and objectives of teaching the subject and balance the historical knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes in the learning process. New values and methodical requirements were included in the general curriculum as well as in the syllabus of history education and in teacher professional development. Keywords: history education, history curriculum, methodology Introduction Changes in history teaching began with the Teachers’ Congress in 1987 when Estonia was still under Soviet rule. The movement towards democratic education emphasised national culture and Estonian ethnicity and increased freedom of choice for schools. In history studies, curriculum with alternative content and a special course of Estonian history was developed. -

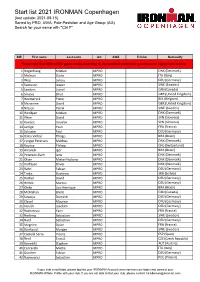

Start List 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (Last Update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for Your Name with "Ctrl F"

Start list 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (last update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for your name with "Ctrl F" BIB First name Last name AG AWA TriClub Nationallty Please note that BIBs will be given onsite according to the selected swim time you choose in registration oniste. 1 Hogenhaug Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 2 Molinari Giulio MPRO ITA (Italy) 3 Wojt Lukasz MPRO DEU (Germany) 4 Svensson Jesper MPRO SWE (Sweden) 5 Sanders Lionel MPRO CAN (Canada) 6 Smales Elliot MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 7 Heemeryck Pieter MPRO BEL (Belgium) 8 Mcnamee David MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 9 Nilsson Patrik MPRO SWE (Sweden) 10 Hindkjær Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 11 Plese David MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 12 Kovacic Jaroslav MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 14 Jarrige Yvan MPRO FRA (France) 15 Schuster Paul MPRO DEU (Germany) 16 Dário Vinhal Thiago MPRO BRA (Brazil) 17 Lyngsø Petersen Mathias MPRO DNK (Denmark) 18 Koutny Philipp MPRO CHE (Switzerland) 19 Amorelli Igor MPRO BRA (Brazil) 20 Petersen-Bach Jens MPRO DNK (Denmark) 21 Olsen Mikkel Hojborg MPRO DNK (Denmark) 22 Korfitsen Oliver MPRO DNK (Denmark) 23 Rahn Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 24 Trakic Strahinja MPRO SRB (Serbia) 25 Rother David MPRO DEU (Germany) 26 Herbst Marcus MPRO DEU (Germany) 27 Ohde Luis Henrique MPRO BRA (Brazil) 28 McMahon Brent MPRO CAN (Canada) 29 Sowieja Dominik MPRO DEU (Germany) 30 Clavel Maurice MPRO DEU (Germany) 31 Krauth Joachim MPRO DEU (Germany) 32 Rocheteau Yann MPRO FRA (France) 33 Norberg Sebastian MPRO SWE (Sweden) 34 Neef Sebastian MPRO DEU (Germany) 35 Magnien Dylan MPRO FRA (France) 36 Björkqvist Morgan MPRO SWE (Sweden) 37 Castellà Serra Vicenç MPRO ESP (Spain) 38 Řenč Tomáš MPRO CZE (Czech Republic) 39 Benedikt Stephen MPRO AUT (Austria) 40 Ceccarelli Mattia MPRO ITA (Italy) 41 Günther Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 42 Najmowicz Sebastian MPRO POL (Poland) If your club is not listed, please log into your IRONMAN Account (www.ironman.com/login) and connect your IRONMAN Athlete Profile with your club. -

Liebe Mitbürgerinnen Und Mitbürger, Vor Ihnen Liegt Die Nunmehr 10

Liebe Mitbürgerinnen und Mitbürger, vor Ihnen liegt die nunmehr 10. Auflage des Sozialwegweisers Wedel. Der Arbeitskreis der sozialpädagogischen Fachkräfte pflegt seit vielen Jahren den Informationsaustausch zwischen den sozialen Einrichtungen dieser Stadt und über die Stadtgrenzen hinaus. Ziel dieser umfassenden Broschüre ist es einmal mehr, die Vielfalt der aktu- ellen, sozialen Beratungs- und Hilfsangebote für Wedel und Umgebung dar- zustellen und somit den richtigen Kontakt für Sie herzustellen. Das ausdauernde Engagement des Arbeitskreises hat in der Vergangenheit zu einer stetigen Verbesserung der Vernetzung der unterschiedlichen Vereine, Initiativen und Einrichtungen im sozialen Bereich beigetragen. Damit ist auch mit dieser Neuauflage des Sozialwegweisers mein Wunsch verbunden, dass allen Rat- und Hilfesuchenden schnellstmöglich an und von richtiger Stelle geholfen wird. Wedel, im Juni 2015 Niels Schmidt Bürgermeister Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, liebe Kolleginnen und Kollegen, Der Wedeler Sozialwegweiser ist ein Handbuch des „Arbeitskreises der sozi- alpädagogischen Fachkräfte Wedel“. Dieser Arbeitskreis ist seit vielen Jahren mit dem Ziel der Vernetzung aller sozialen Einrichtungen aktiv. Die regelmä- ßigen Treffen und dieses Handbuch tragen zu einem intensiven Informations- austausch bei und gewährleisten, dass Hilfesuchende eine qualifizierte Aus- kunft erhalten bzw. dass der richtige Kontakt zu einer der vielen Einrichtun- gen hergestellt wird. Die Angebote werden regelmäßig überarbeitet, so dass wir Ihnen heute die mittlerweile -

Legacy Image

5-(948-~gblb SOWARE ENGINEERING LABORATORY SERIES SEL-95-004 PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTIETH ANNUAL SOFTWARE ENGINEERING WORKSHOP DECEMBER 1995 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 20771 Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Software Engineering Workshop November 29-30,1995 GODDARD SPACE FLIGHT CENTER Greenbelt, Maryland The Software Engineering Laboratory (SEL) is an organization sponsored by the National Aeronautics and Space AdministratiodGoddard Space Flight Center (NASAIGSFC) and created to investigate the effectiveness of software engineering technologies when applied to the development of applications software. The SEL was created in 1976 and has three primary organizational members: NASAIGSFC, Software Engineering Branch The University of Maryland, Department of Computer Science .I Computer Sciences Corporation, Software Engineering Operation The goals of the SEL are (1) to understand the software development process in the GSFC environment; (2) to measure the effects of various methodologies, tools, and models on this process; and (3) to identifjr and then to apply successful development practices. The activities, findings, and recommendations of the SEL are recorded in the Software Engineering Laboratory Series, a continuing series of reports that includes this document. Documents from the Software Engineering Laboratory Series can be obtained via the SEL homepage at: or by writing to: Software Engineering Branch Code 552 Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 2077 1 SEW Proceedings iii The views and findings expressed herein are those of, the authors and presenters and do not necessarily represent the views, estimates, or policies of the SEL. All material herein is reprinted as submitted by authors and presenters, who are solely responsible for compliance with any relevant copyright, patent, or other proprietary restrictions. -

The Long-Lasting Shadow of the Allied Occupation of Austria on Its Spatial Equilibrium

IZA DP No. 10095 The Long-lasting Shadow of the Allied Occupation of Austria on its Spatial Equilibrium Christoph Eder Martin Halla July 2016 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor The Long-lasting Shadow of the Allied Occupation of Austria on its Spatial Equilibrium Christoph Eder University of Innsbruck Martin Halla University of Innsbruck and IZA Discussion Paper No. 10095 July 2016 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. -

The Changing Depiction of Prussia in the GDR

The Changing Depiction of Prussia in the GDR: From Rejection to Selective Commemoration Corinna Munn Department of History Columbia University April 9, 2014 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Volker Berghahn, for his support and guidance in this project. I also thank my second reader, Hana Worthen, for her careful reading and constructive advice. This paper has also benefited from the work I did under Wolfgang Neugebauer at the Humboldt University of Berlin in the summer semester of 2013, and from the advice of Bärbel Holtz, also of Humboldt University. Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………….1 2. Chronology and Context………………………………………………………….4 3. The Geschichtsbild in the GDR…………………………………………………..8 3.1 What is a Geschichtsbild?..............................................................................8 3.2 The Function of the Geschichtsbild in the GDR……………………………9 4. Prussia’s Changing Role in the Geschichtsbild of the GDR…………………….11 4.1 1945-1951: The Post-War Period………………………………………….11 4.1.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………11 4.1.2 Public Symbols and Events: The fate of the Berliner Stadtschloss…14 4.1.3 Film: Die blauen Schwerter………………………………………...19 4.2 1951-1973: Building a Socialist Society…………………………………...22 4.2.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………22 4.2.2 Public Symbols and Events: The Neue Wache and the demolition of Potsdam’s Garnisonkirche…………………………………………..30 4.2.3 Film: Die gestohlene Schlacht………………………………………34 4.3 1973-1989: The Rediscovery of Prussia…………………………………...39 4.3.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………39 4.3.2 Public Symbols and Events: The restoration of the Lindenforum and the exhibit at Sans Souci……………………………………………42 4.3.3 Film: Sachsens Glanz und Preußens Gloria………………………..45 5. -

Stadt Quickborn Kreis Pinneberg Bebauungsplan Nr. 96

Stadt Quickborn Kreis Pinneberg Bebauungsplan Nr. 96 Begründung Auftraggeberin Stadt Quickborn Rathausplatz 1 25451 Quickborn Bearbeiterin Dipl.-Ing. Wiebke Becker Stadtplanerin Bokel, den 19.05.2008 Stadt Quickborn B-Plan Nr. 96 – Stand Mai 2008 Inhalt O:\Daten\105111\Planung\Genehmigungsplanung\Begruend_Quickborn_B96_Mai08.doc 1 Planungsanlass 3 2 Rechtsgrundlagen 4 3 Plangeltungsbereich 4 4 Übergeordnete Planungen 4 5 Festsetzungen 6 5.1 Art und Maß der Nutzung 6 5.2 Bauweise, überbaubare Grundstücksflächen 7 5.3 Grün- und Waldflächen 9 5.4 Örtliche Bauvorschriften über Gestaltung 10 6 Verkehrliche Erschließung 10 7 Ver- und Entsorgung 12 8 Altablagerungen 13 9 Umweltbericht 14 10 Kosten 14 Ingenieurgemeinschaft Klütz & Collegen GmbH 2 Stadt Quickborn B-Plan Nr. 96 – Stand Mai 2008 1 Planungsanlass Der Plangeltungsbereich war Standort der ehemaligen Wetterstation. Seit 2002 ist in den Gebäuden die Bildungs- und Förderstätte Himmelmoor gGmbH (bfh) angesiedelt. Sie ist als gemeinnützige Gesellschaft Tagesförderstätte für schwerst- und mehrfach behinderte Menschen, zudem werden Förderlehrgänge für leistungsschwache und lernbehinderte Jugendliche durchgeführt. Aufgrund der Lage des Plangebietes im Außenbereich sind die Zulassungsvorausset- zungen nach § 35 BauGB für alle zukünftigen Neubaumaßnahmen ausgeschöpft. Zur Sicherung des Standortes der Bildungs- und Förderstätte Himmelmoor und Schaffung von Entwicklungsoptionen wird daher dieser Bebauungsplan aufgestellt. Gem. Aufstellungsbeschluss vom 13.01.2005 soll das Plangebiet als Sondergebiet -

Daten Fakten 2020/2021 Stadt Kempten (Allgäu)

Zahlen Daten 2 0/21Fakten 1 2020/2021 Stadt Kempten (Allgäu) Inhalt Zahlen · Daten · Fakten 2020/2021 5 Eckdaten Stadt Kempten (Allgäu) 6 Amtlicher Bevölkerungsstand 6 Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung 7 Bevölkerungsbewegung 7 Alterspyramide 8 Wohnraum 8 Gesundheitswesen, Soziales 9 Kommunalabgaben 10 Verarbeitendes Gewerbe 11 Handwerk 11 Arbeitsmarkt 12 Arbeitnehmer 13 Berufspendler 14 Tourismus 14 KFZ Bestand 15 Schulen 16 Hochschule 17 Studierende 19 Impressum 3 Eckdaten 2020/2021 Einwohner Insgesamt (31.12.2019) 71.044 davon weiblich 35.929 davon Ausländer 11.652 davon nur Hauptwohnsitz 69.732 Fläche in ha 6.330,8 Flächennutzung Gewässer 1,9 % Industrie und Gewerbe 5,7 % Landwirtschaft 50,6 % sonstige 5,1 % sonstige Vegetation 1,4 % Sport, Freizeit und Erholung 3,8 % Verkehr 8,3 % Wald und Gehölz 13,2 % Wohnbau 9,9 % Bevölkerungsdichte Einwohner/ha 11,2 Arbeitsmarkt Erwerbstätige am Arbeitsort (Jahresdurchschnitt 2017) 51.900 Sozialversicherungspflichtig Beschäftigte (30.06.2019) 37.186 davon weiblich 18.544 davon Ausländer 4.614 Arbeitslose (Basis: alle ziv. Erwerbspers. – Durchschn. 2019) 3,2 % Bruttoinlandsprodukt Mio. EUR 2017 3.926 EUR je Einwohner 57.802 Kennziffern Einzelhandelskaufkraft (Index) 2019 101,8* Einzelhandelsumsatz (Index) 2019 165,7* Einzelhandelszentralität (Index) 2019 162,7 * *Deutschland = 100 Steuerhebesätze Gewerbesteuer 387 v.H. Grundsteuer A 275 v.H. Grundsteuer B 420 v.H. Bodenrichtwerte für Gewerbeflächen EUR/m2 Bühl Ost** 90,00 Bühl Nord-Ost** 90,00 Gewerbe- und Industriepark Ursulasried** 50,00 bis 80,00 -

Flyer Informationen Zum Studium 27-11-2019.Indd

Succeed in your studies and enjoy your time in Ansbach Why choose Ansbach? Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Become part of Ansbach University’s vibrant student community! A Residenzstrasse 8 warm welcome awaits you and plenty of support to help you succeed. 91522 Ansbach Germany Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Phone: +49 981 4877 – 0 Ansbach University of Applied Sciences offers a wide range of study Fax: +49 981 4877 – 188 programmes with a focus on practical training and employability www.hs-ansbach.de/en without tuition fees. Teaching in small groups, close mentoring by dedicated staff, high-tech laboratories, and a green campus in International Offi ce friendly surroundings all combine to make Ansbach University an Bettina Huhn, M.A. (Head) ideal place to study. Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 145 Sandra Sauter Ansbach Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 545 Ansbach is a beautiful town in Bavaria with lots of leisure activities, [email protected] safe surroundings and a low cost of living. Located in the heart of Germany, close to Nuremberg, it allows easy access to the major cities www.hs-ansbach.de of Germany and Europe. The campus lies within walking distance of www.facebook.com/studieren.in.franken Studying in Ansbach – the old town centre with its historic architecture and landmarks and hs.ansbach its multitude of shops and cafés. Information for Services Frankfurt international students Berlin International students receive a wide range of personal support from the International Offi ce. This includes an orientation week Strasbourg . Business – Engineering – Media at the start of semester, German language courses available 2 hours both pre-semester and during the regular semester studies, and Stuttgart. -

Flyer Informationen Zum Studium 08-2020 EN.Indd

Succeed in your studies and enjoy your time in Ansbach Why choose Ansbach? Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Become part of Ansbach University’s vibrant student community! A Residenzstrasse 8 warm welcome awaits you and plenty of support to help you succeed. 91522 Ansbach Germany Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Phone: +49 981 4877 – 0 Ansbach University of Applied Sciences off ers a wide range of study Fax: +49 981 4877 – 188 programmes with a focus on practical training and employability www.hs-ansbach.de/en without tuition fees. Teaching in small groups, close mentoring by dedicated staff , high-tech laboratories, and a green campus in International Offi ce friendly surroundings all combine to make Ansbach University an Bettina Huhn, M.A. (Head) ideal place to study. Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 145 Sandra Sauter Ansbach Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 545 Ansbach is a beautiful town in Bavaria with lots of leisure activities, [email protected] safe surroundings and a low cost of living. Located in the heart of Germany, close to Nuremberg, it allows easy access to the major www.hs-ansbach.de cities of Germany and Europe. The campus lies within walking www.facebook.com/studieren.in.franken Studying in Ansbach – distance of the old town centre with its historic architecture and hs.ansbach landmarks and its multitude of shops and cafés. Information for Services Frankfurt international students Berlin International students receive a wide range of personal support from the International Offi ce. This includes an orientation week Strasbourg . Business – Engineering – Media at the start of semester, German language courses available 2 hours both pre-semester and during the regular semester studies, and Stuttgart. -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of December, 2009 Club Fam

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of December, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 111BS 21847 AUGSBURG 0 0 0 35 35 District 111BS 21848 AUGSBURG RAETIA 0 0 1 49 50 District 111BS 21849 BAD REICHENHALL 0 0 2 25 27 District 111BS 21850 BAD TOELZ 0 0 0 36 36 District 111BS 21851 BAD WORISHOFEN MINDELHEIM 0 0 0 43 43 District 111BS 21852 PRIEN AM CHIEMSEE 0 0 0 36 36 District 111BS 21853 FREISING 0 0 0 48 48 District 111BS 21854 FRIEDRICHSHAFEN 0 0 0 43 43 District 111BS 21855 FUESSEN ALLGAEU 0 0 1 33 34 District 111BS 21856 GARMISCH PARTENKIRCHEN 0 0 0 45 45 District 111BS 21857 MUENCHEN GRUENWALD 0 0 1 43 44 District 111BS 21858 INGOLSTADT 0 0 0 62 62 District 111BS 21859 MUENCHEN ISARTAL 0 0 1 27 28 District 111BS 21860 KAUFBEUREN 0 0 0 33 33 District 111BS 21861 KEMPTEN ALLGAEU 0 0 0 45 45 District 111BS 21862 LANDSBERG AM LECH 0 0 1 36 37 District 111BS 21863 LINDAU 0 0 2 33 35 District 111BS 21864 MEMMINGEN 0 0 0 57 57 District 111BS 21865 MITTELSCHWABEN 0 0 0 42 42 District 111BS 21866 MITTENWALD 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21867 MUENCHEN 0 0 0 35 35 District 111BS 21868 MUENCHEN ARABELLAPARK 0 0 0 32 32 District 111BS 21869 MUENCHEN-ALT-SCHWABING 0 0 0 34 34 District 111BS 21870 MUENCHEN BAVARIA 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21871 MUENCHEN SOLLN 0 0 0 29 29 District 111BS 21872 MUENCHEN NYMPHENBURG 0 0 0 32 32 District 111BS 21873 MUENCHEN RESIDENZ 0 0 0 22 22 District 111BS 21874 MUENCHEN WUERMTAL 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21875 -

Abuses Under Indictment at the Diet of Augsburg 1530 Jared Wicks, S.J

ABUSES UNDER INDICTMENT AT THE DIET OF AUGSBURG 1530 JARED WICKS, S.J. Gregorian University, Rome HE MOST recent historical scholarship on the religious dimensions of Tthe Diet of Augsburg in 1530 has heightened our awareness and understanding of the momentous negotiations toward unity conducted at the Diet.1 Beginning August 16, 1530, Lutheran and Catholic represent atives worked energetically, and with some substantial successes, to overcome the divergence between the Augsburg Confession, which had been presented on June 25, and the Confutation which was read on behalf of Emperor Charles V on August 3. Negotiations on doctrine, especially on August 16-17, narrowed the differences on sin, justification, good works, and repentance, but from this point on the discussions became more difficult and an impasse was reached by August 21 which further exchanges only confirmed. The Emperor's draft recess of September 22 declared that the Lutheran confession had been refuted and that its signers had six months to consider acceptance of the articles proposed to them at the point of impasse in late August. Also, no further doctrinal innovations nor any more changes in religious practice were to be intro duced in their domains.2 When the adherents of the Reformation dis sented from this recess, it became unmistakably clear that the religious unity of the German Empire and of Western Christendom was on the way to dissolution. But why did it come to this? Why was Charles V so severely frustrated in realizing the aims set for the Diet in his conciliatory summons of January 21, 1530? The Diet was to be a forum for a respectful hearing of the views and positions of the estates and for considerations on those steps that would lead to agreement and unity in one church under Christ.3 1 The most recent stage of research began with Gerhard Müller, "Johann Eck und die Confessio Augustana/' Quellen und Forschungen aus italienischen Archiven und Biblio theken 38 (1958) 205-42, and continued in works by Eugène Honèe and Vinzenz Pfhür, with further contributions of G.