Optical Spectroscopy of Graphene from the Far Infrared to the Ultraviolet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Far Infrared Radiation (FIR): Its Biological Effects and Medical Applications

DOI 10.1515/plm-2012-0034 Photon Lasers Med 2012; 1(4): 255–266 Review Fatma Vatansever and Michael R. Hamblin * Far infrared radiation (FIR): Its biological effects and medical applications Ferne Infrarotstrahlung: Biologische Effekte und medizinische Anwendungen Abstract am menschlichen K ö rper entwickelt werden. Spezielle Lampen und Saunas, die reine FIR-Strahlung (ohne Anteile von Nahinfrarot- und Mittelinfrarotstrahlung) Far infrared (FIR) radiation ( λ = 3 – 100 μ m) is a subdivision liefern, sind immer sicherer und effektiver geworden und of the electromagnetic spectrum that has been investi- werden verbreitet f ü r therapeutische Zwecke genutzt. gated for biological effects. The goal of this review is to Fasern, die mit FIR-emittierenden Keramik-Nanopartikeln cover the use of a further sub-division (3 – 12 μ m) of this impr ä gniert und zu Stoffen weiterverarbeitet werden, waveband, that has been observed in both in vitro and finden Verwendung als Kleidung oder Verbandsstoffe, die in vivo studies, to stimulate cells and tissue, and is consid- aufgrund der generierten FIR-Strahlung gesundheitliche ered a promising treatment modality for certain medical Vorteile bewirken k ö nnen. conditions. Technological advances have provided new techniques for delivering FIR radiation to the human body. Schl ü sselw ö rter: Ferne Infrarotstrahlung (FIR); Strah- Specialty lamps and saunas, delivering pure FIR radiation lungsw ärme; Schwarzk ö rperstrahlung; biogenetische (eliminating completely the near and mid infrared bands), Strahlen; FIR-emittierende Keramiken und Fasern; have became safe, effective, and widely used sources to Infrarotsauna. generate therapeutic effects. Fibers impregnated with FIR emitting ceramic nanoparticles and woven into fabrics, are being used as garments and wraps to generate FIR *Corresponding author: Michael R. -

Far Infrared Radiation Exposure

INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON NON‐IONIZING RADIATION PROTECTION ICNIRP STATEMENT ON FAR INFRARED RADIATION EXPOSURE PUBLISHED IN: HEALTH PHYSICS 91(6):630‐645; 2006 ICNIRP PUBLICATION – 2006 ICNIRP Statement ICNIRP STATEMENT ON FAR INFRARED RADIATION EXPOSURE The International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection* INTRODUCTION the health hazards associated with these hot environ- ments. Heat strain and discomfort (thermal pain) nor- THE INTERNATIONAL Commission on Non Ionizing Radia- mally limit skin exposure to infrared radiation levels tion Protection (ICNIRP) currently provides guidelines below the threshold for skin-thermal injury, and this is to limit human exposure to intense, broadband infrared particularly true for sources that emit largely IR-C. radiation (ICNIRP 1997). The guidelines that pertained Furthermore, limits for lengthy infrared exposures would to infrared radiation (IR) were developed initially with an have to consider ambient temperatures. For example, an aim to provide guidance for protecting against hazards infrared irradiance of 1 kW mϪ2 (100 mW cmϪ2)atan from high-intensity artificial sources and to protect work- ambient temperature of 5°C can be comfortably warm- ers in hot industries. Detailed guidance for exposure to ing, but at an ambient temperature of 30°C this irradiance longer far-infrared wavelengths (referred to as IR-C would be painful and produce severe heat strain. There- radiation) was not provided because the energy at longer fore, ICNIRP provided guidelines to limit skin exposure wavelengths from most lamps and industrial infrared to pulsed sources and very brief exposures where thermal sources of concern actually contribute only a small injury could take place faster than the pain response time fraction of the total radiant heat energy and did not and where environmental temperature and the irradiated require measurement. -

The Space Infrared Interferometric Telescope (SPIRIT): High- Resolution Imaging and Spectroscopy in the Far-Infrared

Leisawitz, D. et al., J. Adv. Space Res., in press (2007), doi:10.1016/j.asr.2007.05.081 The Space Infrared Interferometric Telescope (SPIRIT): High- resolution imaging and spectroscopy in the far-infrared David Leisawitza, Charles Bakera, Amy Bargerb, Dominic Benforda, Andrew Blainc, Rob Boylea, Richard Brodericka, Jason Budinoffa, John Carpenterc, Richard Caverlya, Phil Chena, Steve Cooleya, Christine Cottinghamd, Julie Crookea, Dave DiPietroa, Mike DiPirroa, Michael Femianoa, Art Ferrera, Jacqueline Fischere, Jonathan P. Gardnera, Lou Hallocka, Kenny Harrisa, Kate Hartmana, Martin Harwitf, Lynne Hillenbrandc, Tupper Hydea, Drew Jonesa, Jim Kellogga, Alan Koguta, Marc Kuchnera, Bill Lawsona, Javier Lechaa, Maria Lechaa, Amy Mainzerg, Jim Manniona, Anthony Martinoa, Paul Masona, John Mathera, Gibran McDonalda, Rick Millsa, Lee Mundyh, Stan Ollendorfa, Joe Pellicciottia, Dave Quinna, Kirk Rheea, Stephen Rineharta, Tim Sauerwinea, Robert Silverberga, Terry Smitha, Gordon Staceyf, H. Philip Stahli, Johannes Staguhn j, Steve Tompkinsa, June Tveekrema, Sheila Walla, and Mark Wilsona a NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD b Department of Astronomy, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, USA c California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA d Lockheed Martin Technical Operations, Bethesda, Maryland, USA e Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, DC, USA f Department of Astronomy, Cornell University, Ithaca, USA g Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA h Astronomy Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, USA i NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama, USA j SSAI, Lanham, Maryland, USA ABSTRACT We report results of a recently-completed pre-Formulation Phase study of SPIRIT, a candidate NASA Origins Probe mission. SPIRIT is a spatial and spectral interferometer with an operating wavelength range 25 - 400 µm. -

Modeling Infrared and Combination Infrared-Microwave Heating of Foods in an Oven

MODELING INFRARED AND COMBINATION INFRARED-MICROWAVE HEATING OF FOODS IN AN OVEN A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Ful¯llment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Marialuci Frangipani Almeida January 2005 °c Marialuci Frangipani Almeida 2005 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED MODELING INFRARED AND COMBINATION INFRARED-MICROWAVE HEATING OF FOODS IN AN OVEN Marialuci Frangipani Almeida, Ph.D. Cornell University 2005 A quantitative, model-based understanding of heat exchange in infrared and com- bined infrared-microwave heating of food inside an oven is developed. The research is divided into three parts: measurement of optical properties, radiative heat transfer analysis and combined microwave-radiative heat transfer analysis. Optical proper- ties of reflectance, absorptance and transmittance in a potato tissue are measured as a function of wavelength, using a spectroradiometer. Penetration of energy is higher for halogen lamps that emit in the near- and mid-infrared range, compared to ceramic rods that emit mostly in the far infrared range. Reflectance in the near infrared range increases with moisture content of the food, thus decreasing the en- ergy coupled. Surface structure has signi¯cant influence on the optical properties. A 3-D radiative heat exchange model of an oven-food system is developed using a commercial ¯nite-element package. The air in the oven is assumed transparent to the radiation. Heat conduction is assumed in the entire oven (food and air) for the short duration. The wavelength dependence of emissivity (non-gray surface) is found to signi¯cantly a®ect the surface radiative flux and the use of a non-gray model is recommended for such materials, although simpli¯cation of the emissiv- ity variation is required to keep the computation time reasonable. -

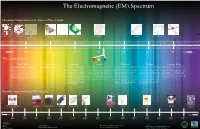

Radio Waves: Microwaves: Infrared: Visible: Ultraviolet: X-Rays: Gamma

The Electromagnetic (EM) Spectrum Hawaiian Comparisons to the Sizes of Wavelengths: Aloha Tower Aloha Stadium Hale Kamehameha Point of a Needle Plant Cell Bacteria Protein Water Molecule Atom (Hawaiian House) Butterfly 3 -2 -5 -6 -8 -10 -12 Longer 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Shorter Wavelength (Meters): Radio Waves: Microwaves: Infrared: Visible: Ultraviolet: X-Rays: Gamma Rays: Radio waves have the longest wavelength in the EM Since microwaves can penetrate haze, light Infrared light has a range of wavelengths Visible light waves are the only waves in spec- Ultraviolet light is invisible to the human As the wavelengths of the spectrum de- Gamma rays have the smallest wavelength, spectrum. As implied, radio waves bring music to ra- rain, snow, clouds and smoke, these waves like visible light. “Near infrared” light is trum that humans can see. These waves are eyes, but some insects, like bumblebees, have crease, the energy increases, such as how but have the most energy out of all of the other dios, but they also provide signals to cell phones, tele- are ideal for viewing the Earth from space. closest in wavelength to visible light and seen in a range of colors with red having the proven to be able to see ultraviolet light. The x-rays tend to act more like a particle than waves in the spectrum. These waves are gener- visions, etc. Radio waves are received at an estimate The wavelength of micro waves in a mi- “far infrared” is closer to the microwave re- longest wavelength and violet (purple) having ultraviolet part of the spectrum is divided into a wave. -

An Evolvable Space Telescope for the Far Infrared Surveyor Mission

An Evolvable Space Telescope for the Far Infrared Surveyor Mission C. F. Lilliea, R.S. Polidanb J. B. Breckinridgec, H. A. MacEwend, M. R. Flanneryb and D. R. Daileyb aLillie Consulting LLC, bNorthrop Grumman Aerospace Systems, cBreckinridge Associates LLC, dReviresco LLC 1. Introduction and overview In an era of flat NASA budgets, we need to find more affordable ways to build large space telescopes. We believe the root cause for the delay or cancellation of a Flagship class mission is the annual cost of the mission. When development costs consume too large a share of the annual NASA budget it threatens all other missions, and the science community and NASA must consider drastic measures to reduce the annual cost of the Flagship mission: i.e., schedule extension, down-sizing or cancellation. To be affordable, future flagship observatories must identify and implement new technology AND new development concepts, as well as providing the greatly improved resolution and light collecting power necessary to answer cutting-edge science questions. We have been studying observatory architectures where the design, development, construction, and launch of the future large space telescope will be conducted in several stages, each providing a complete telescope fully capable of forefront scientific observations. One approach to building future large space observatories that is intended to break the cost curve and enable large (>10 m) telescopes to be developed within a flat NASA budget is an Evolvable Space Telescope (Proc. SPIE 9143-40, Space Telescopes and Instrumentation, 2014). Stage 1 would form the core of the observatory and provide a major improvement over existing observatories operating at the planned launch date. -

The Electro Magnetic Spectrum

The Electro Magnetic Spectrum Understanding Infrared Light Energy Infrared light lies between the light”. The human eye is not capable visible and microwave portions of the of “seeing” radiation with wavelengths electromagnetic spectrum. Infrared light outside the visible spectrum. The has a range of wavelengths, just like visible colors from shortest to longest visible light has wavelengths that range wavelength are: violet, blue, green, yellow, from red light to violet. “Near infrared” orange, and red. Ultraviolet radiation has light is closest in wavelength to visible a shorter wavelength than the visible light and “far infrared” is closer to the violet light. Infrared radiation has a longer microwave region of the electromagnetic wavelength than visible red light. The spectrum. The longer, far infrared white light is a mixture of all of the colors wavelengths are about the size of a pin of the visible spectrum. Black is a total head and the shorter, near infrared ones absence of light. are the size of cells, or are microscopic. Earth’s most important energy source is Our eyes are sensitive to light which the Sun. Sunlight consists of the entire lies in a very small region of the electromagnetic spectrum. electromagnetic spectrum labeled “visible Colors We Can’t See Energy with wavelengths Energy with wavelengths too short for humans to see too long for humans to see Energy with wavelengths too short to see Energy whose wavelength is too long to is “bluer than blue”. Light with such short see is “redder than red”. Light with such wavelengths is called “Ultraviolet” light. long wavelengths is called “Infrared” light. -

Understanding Color-Infrared Photographs

Understanding Color-Infrared Photographs Images obtained by satellites and high- apart and are analogous to light wave- altitude aircraft give engineers and scien- lenths and how closely they are spaced. tists a tool to study landforms, vegetation health patterns, environmental pollution, Other parts of the spectrumCsuch as the and other effects of human activities on invisible near-infrared wavelengthsCcan the planet’s surface. be recorded by either electronic sensors or special photographic films sensitive to Satellites and high-altitude aircraft these wavelengths. These sensors and equipped to record scenes of the Earth use films record the energy reflected by the both visible and invisible parts of the ground and the Sun’s spectral energy. The electromagnetic spectrum. Near-infrared color-infrared film images referred to in light is invisible to the human eye, but this fact sheet should not be confused adding it to these images allows scientists with electronic thermography (thermal to “see” the surface of the Earth in other recordings), a process in which long-wave than natural colors. The result is “color- or “far-infrared” radiation is electronically infrared” photography. detected and subsequently displayed at visible wavelengths. Near-infrared and The electromagnetic spectrum is the sci- visible wavelengths that are simultaneous- entific term for the collective types of ly recorded combine to provide a unique light and energy emitted from the Sun. view of the Earth’s vegetation and other NASA color-infrared photograph--New Orleans, La. The part of the spectrum visible to the features of the planet’s surface. human eye is the normal rainbow of col- infrared film. -

Clinical Trials & Studies

FAR INFRARED WAVELENGTH TREATMENT FOR LOW BACK PAIN THERMOTEX THERAPY SYSTEM INFRARED HEATING PAD VERSUS CONVENTIONAL HEATING PAD AND HOT TOWEL THE EFFICACY OF THE THERMOTEX INFRARED HEATING BLANKET UPON THE STANDARDBRED RACEHORSE Work 53 (2016) 157–162 157 DOI:10.3233/WOR-152152 IOS Press Far infrared wavelength treatment for low back pain: Evaluation of a non-invasive device a, b Frank Ervolino ∗ and Ronald Gazze aPrivate Practice, Stuart, FL, USA bPrivate Practice, North Palm Beach, FL, USA Received 16 October 2013 Accepted 2 May 2014 Abstract. BACKGROUND: Low back pain is a significant cause of lost workplace productivity. Identification of simple, safe, and effective treatment strategies that can be used in the workplace are needed. OBJECTIVE: To assess whether far-infrared therapy (FIR) can ameliorate chronic back pain in office workers with the hypothesis that back pain could be effectively treated while at work with minimal interruption to the normal working day. METHODS: In a cohort study, 50 subjects with low back pain of at least six months duration were recruited from a Florida corporation. The subjects were instructed to use a FIR pad placed in their chairs in contact with the affected area while on the job over a 4 week period for at least 45 minutes a day during workdays. The FIR device used for the study was the Thermotex TTS Platinum Pad, a widely available FDA-registered medical device with preclinical data on its deep heating effects. The outcomes were assessed using subscales of the SF-36v2. RESULTS: Results showed statistically significant changes in 9 of 10 SF-36 subscales including both physical and mental components with a near significant improvement to General Health. -

Infrared Astronomy: More Than Our Eyes Can See

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Infrared Astronomy: More Than Our Eyes Can See VISIBLE LIGHT INFRARED These views of the constellation Orion dramatically illustrate the difference between the familiar, visible-light view and the richness of the universe that is invisible to our eyees, though accessible via other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. Infrared Astronomy: More Than Our Eyes Can See Invisible Light. In 1800, William Herschel discovered an invisible their lives. The ISM is the reservoir of material from which new stars microns during the 5- 1/2 year lifetime of its cryogen supply. (Spitzer form of radiation just beyond the red portion of the visible spectrum. form. Clouds of interstellar dust and gas are easily detected at long continues to operate part of its near infrared camera, IRAC, at ambi- He named this form of radiation infrared (“below” red). (Herschel infrared wavelengths (about 100 times longer than visible radiation). ent temperature.) was already world-famous for having discovered the planet Uranus.) To see the newborn stars embedded in these clouds of dust and gas, •The Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) is a Herschel’s discovery was the first step in establishing the existence astronomers depend instead on observations made at short infrared Boeing 747SP airplane modified to carry a telescope with an effec- of what we now call the electromagnetic spectrum. Visible light and wavelengths that penetrate the obscuring dust. tive diameter of 2.5 meters (100 inches). Flying above 12km (39,000 infrared radiation are just two of the many types of electromagnetic Building New Planets. -

Far Infrared Therapy

Far Infrared Therapy Ancient Healing The electromagnetic spectrum can be subdivided into regions according to wavelength, e.g. ultraviolet, infrared, microwave and radio frequency. Infrared (IFR) falls between visible light and microwaves. Far Infrared (FIR) is at the long wavelength end of the infrared region. Our bodies and the sun emit FIR energy at all times. Far Infrared Therapy uses these waves of energy to slightly elevate the surface temperature of the body to enhance our body’s functioning on multiple levels. For thousands of years FIR therapy has been used in Japan, China, India, Americas and ancient Rome to gently heal, soothe and detoxify the body. The Health Benefits of Far Infrared Ordinary heat is mostly absorbed at skin level and raises the skin temperature, whereas FIR rays easily penetrate the skin. Unlike short waves (like X-Rays) the effects are very beneficial: Expands blood vessels to improve blood flow Encourages the formation of new blood vessels Helps release toxins FIR is a safe method to accelerate healing of the skin or muscle, provide effective pain relief, reduce in- flammation, improve lymph circulation, improve immune response and decrease joint stiffness. FIR can help: Pain Relief (e.g. menstrual cramps, muscle sprains) Poor Circulation (e.g. Raynaud’s disease) Inflammation (e.g. Rheumatoid Arthritis) Healing (e.g. of skin, muscle, nerves, etc.) FabRoc™ and Far Infrared FabRoc™ from exo² is a lightweight, intelligent, polymeric fabric which produces far infrared heat. It is safe to use, contains no wires and cannot overheat. It produces a uniform heat (with no hot spots) and is therefore comfortable to use in close prox- imity to the skin such as in clothing, body wraps, etc. -

10 Comparing Colors

Comparing Colors 10 L A B O R ATO RY 1 CLASS SESSION ACTIVITY OVERVIEW NGSS CONNECTIONS Students first observe that visible light can be separated into different colors. Students then conduct an investigation to collect evidence that indicates that different colors of light carry different amounts of energy. In their final analysis, students analyze and interpret light transmission graphs for three different sunglass lenses. They determine which sunglass lens (structure) provides the best protection (function) for the eyes. NGSS CORRELATION Performance Expectation Working towards MS-PS4-2: Develop and use a model to describe that waves are reflected, absorbed, or transmitted through various materials. Disciplinary Core Ideas MS-PS4.B.1 Electromagnetic Radiation: When light shines on an object, it is reflected, absorbed, or transmitted through the object, depending on the object’s material and the frequency (color) of the light. MS-PS4.B.3 Electromagnetic Radiation: A wave model of light is useful for explaining brightness, color, and the frequency-dependent bending of light at a surface between media. Science and Engineering Practices Planning and Carrying Out Investigations: Conduct an investigation to produce data to serve as the basis for evidence that meets the goals of an investigation. Crosscutting Concepts Structure and Function: Structures can be designed to serve particular functions by taking into account properties of different materials, and how materials can be shaped and used. WAVES 112 ACTIVITY 10 COMPARING COLORS Common Core State Standards—ELA/Literacy RST.6-8.3: Follow precisely a multistep procedure when carrying out experiments, taking measurements, or performing technical tasks.